IEC TR 62131-6:2017

(Main)Environmental conditions - Vibration and shock of electrotechnical equipment - Part 6: Transportation by propeller aircraft

Environmental conditions - Vibration and shock of electrotechnical equipment - Part 6: Transportation by propeller aircraft

IEC TR 62131-6:2017(E) reviews the available dynamic data relating to the transportation of electrotechnical equipment. The intent is that from all the available data an environmental description will be generated and compared to that set out in IEC 60721 (all parts).

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 19-Sep-2017

- Technical Committee

- TC 104 - Environmental conditions, classification and methods of test

- Drafting Committee

- WG 15 - TC 104/WG 15

- Current Stage

- PPUB - Publication issued

- Start Date

- 20-Sep-2017

- Completion Date

- 17-Oct-2017

Overview

IEC TR 62131-6:2017 is a Technical Report from the IEC that reviews measured dynamic data for the transportation of electrotechnical equipment by propeller aircraft. Its primary intent is to compile an environmental description (vibration and shock) from available flight and landing measurements and to compare that environment with the classifications and severities given in IEC 60721 (all parts). This report is Part 6 of the IEC 62131 series on environmental vibration and shock.

Key topics and technical content

- Scope and data quality: assessment of measurement sources, record durations and error estimates for flight data.

- Measured platforms: surveys and flight tests for multiple propeller aircraft including Britten‑Norman Islander, BAe Jetstream, BAe HS 748, Lockheed C‑130 (including C130J variant), Transall C160 and Airbus A400M.

- Instrumentation and locations: descriptions/diagrams of sensor locations (cabin, fuselage, propeller plane, floor) used to capture vibration and shock.

- Vibration analysis: cruise, climb, take‑off and landing vibration spectra; blade‑passing frequency effects; background random vibration and overall rms severity comparisons.

- Landing shocks: measured shock pulses in vertical, lateral and longitudinal axes; shock characterization and comparisons.

- Data comparisons: intra‑source (within one aircraft dataset) and inter‑source (between different aircraft) comparisons to identify typical severities and spectral features.

- Derived test severities and recommendations: guidance for selecting vibration and shock test levels representative of propeller aircraft transport.

- Comparisons with IEC 60721 & test procedures: mapping measured environments to IEC 60721 classifications and referencing practical test procedures (e.g., IEC 60068‑2‑27/29) for shock testing.

Practical applications and users

This Technical Report is useful for:

- Design and test engineers developing or qualifying electrotechnical and avionics equipment for transport by propeller aircraft.

- Test laboratories selecting representative vibration/shock test profiles and durations.

- Packaging and logistics teams assessing mechanical protection requirements during air transport.

- Certification bodies and standards developers seeking empirical data to validate and refine environmental classifications. Benefits include improved selection of test severities, alignment of qualification procedures with real transport environments, and informed decisions on mounting, damping and packaging to mitigate damage from propeller‑aircraft vibrations and landing shocks.

Related standards

- IEC 62131 series (Environmental conditions – Vibration and shock)

- IEC 60721 (Classification of environmental conditions)

- IEC 60068‑2‑27 and IEC 60068‑2‑29 (common shock test procedures referenced for comparison)

Keywords: IEC TR 62131-6:2017, vibration and shock, electrotechnical equipment, propeller aircraft, transportation environment, IEC 60721, landing shocks, vibration spectra, test severities.

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

BSI Group

BSI (British Standards Institution) is the business standards company that helps organizations make excellence a habit.

Bureau Veritas

Bureau Veritas is a world leader in laboratory testing, inspection and certification services.

DNV

DNV is an independent assurance and risk management provider.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

IEC TR 62131-6:2017 is a technical report published by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Its full title is "Environmental conditions - Vibration and shock of electrotechnical equipment - Part 6: Transportation by propeller aircraft". This standard covers: IEC TR 62131-6:2017(E) reviews the available dynamic data relating to the transportation of electrotechnical equipment. The intent is that from all the available data an environmental description will be generated and compared to that set out in IEC 60721 (all parts).

IEC TR 62131-6:2017(E) reviews the available dynamic data relating to the transportation of electrotechnical equipment. The intent is that from all the available data an environmental description will be generated and compared to that set out in IEC 60721 (all parts).

IEC TR 62131-6:2017 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 01 - GENERALITIES. TERMINOLOGY. STANDARDIZATION. DOCUMENTATION; 03.120.20 - Product and company certification. Conformity assessment; 19.040 - Environmental testing; 19.080 - Electrical and electronic testing; 71.040.20 - Laboratory ware and related apparatus. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

IEC TR 62131-6:2017 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

IEC TR 62131-6 ®

Edition 1.0 2017-09

TECHNICAL

REPORT

colour

inside

Environmental conditions – Vibration and shock of electrotechnical equipment –

Part 6: Transportation by propeller aircraft

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from

either IEC or IEC's member National Committee in the country of the requester. If you have any questions about IEC

copyright or have an enquiry about obtaining additional rights to this publication, please contact the address below or

your local IEC member National Committee for further information.

IEC Central Office Tel.: +41 22 919 02 11

3, rue de Varembé Fax: +41 22 919 03 00

CH-1211 Geneva 20 info@iec.ch

Switzerland www.iec.ch

About the IEC

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is the leading global organization that prepares and publishes

International Standards for all electrical, electronic and related technologies.

About IEC publications

The technical content of IEC publications is kept under constant review by the IEC. Please make sure that you have the

latest edition, a corrigenda or an amendment might have been published.

IEC Catalogue - webstore.iec.ch/catalogue Electropedia - www.electropedia.org

The stand-alone application for consulting the entire The world's leading online dictionary of electronic and

bibliographical information on IEC International Standards, electrical terms containing 20 000 terms and definitions in

Technical Specifications, Technical Reports and other English and French, with equivalent terms in 16 additional

documents. Available for PC, Mac OS, Android Tablets and languages. Also known as the International Electrotechnical

iPad. Vocabulary (IEV) online.

IEC publications search - www.iec.ch/searchpub IEC Glossary - std.iec.ch/glossary

The advanced search enables to find IEC publications by a 65 000 electrotechnical terminology entries in English and

variety of criteria (reference number, text, technical French extracted from the Terms and Definitions clause of

committee,…). It also gives information on projects, replaced IEC publications issued since 2002. Some entries have been

and withdrawn publications. collected from earlier publications of IEC TC 37, 77, 86 and

CISPR.

IEC Just Published - webstore.iec.ch/justpublished

Stay up to date on all new IEC publications. Just Published IEC Customer Service Centre - webstore.iec.ch/csc

details all new publications released. Available online and If you wish to give us your feedback on this publication or

also once a month by email. need further assistance, please contact the Customer Service

Centre: csc@iec.ch.

IEC TR 62131-6 ®

Edition 1.0 2017-09

TECHNICAL

REPORT

colour

inside

Environmental conditions – Vibration and shock of electrotechnical equipment –

Part 6: Transportation by propeller aircraft

INTERNATIONAL

ELECTROTECHNICAL

COMMISSION

ICS 19.040 ISBN 978-2-8322-4828-7

– 2 – IEC TR 62131-6:2017 © IEC 2017

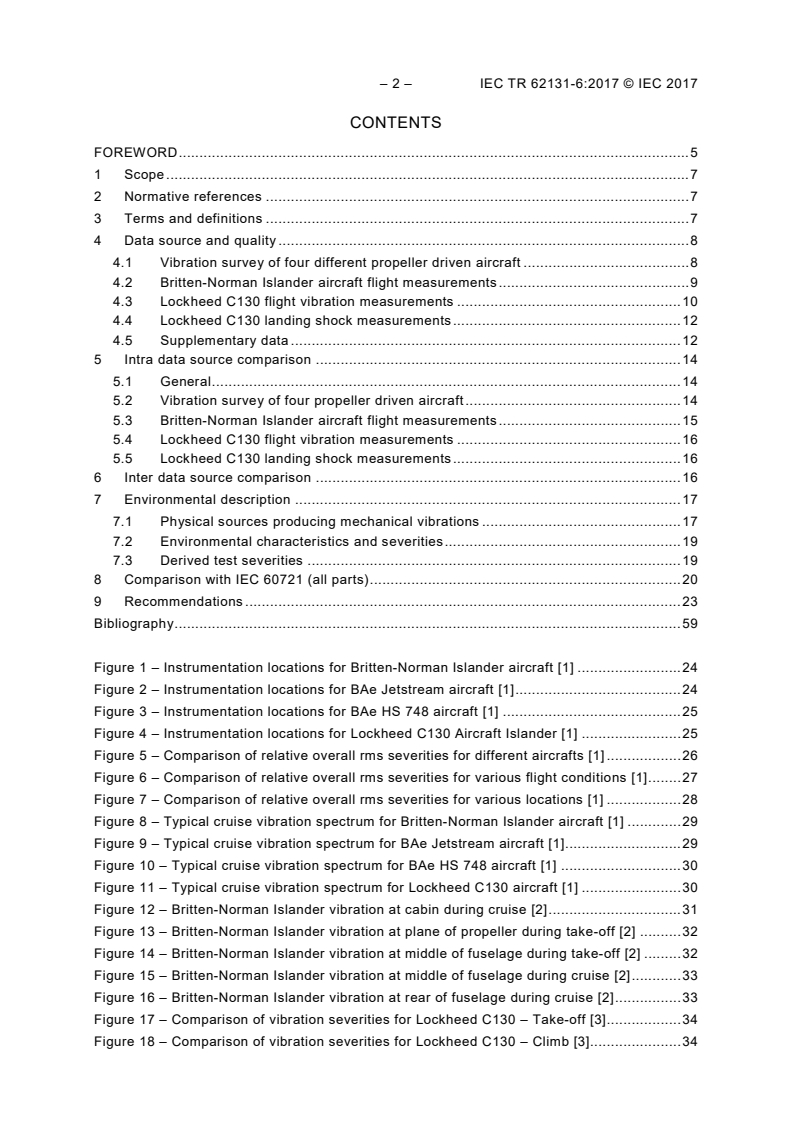

CONTENTS

FOREWORD . 5

1 Scope . 7

2 Normative references . 7

3 Terms and definitions . 7

4 Data source and quality . 8

4.1 Vibration survey of four different propeller driven aircraft . 8

4.2 Britten-Norman Islander aircraft flight measurements . 9

4.3 Lockheed C130 flight vibration measurements . 10

4.4 Lockheed C130 landing shock measurements . 12

4.5 Supplementary data . 12

5 Intra data source comparison . 14

5.1 General . 14

5.2 Vibration survey of four propeller driven aircraft . 14

5.3 Britten-Norman Islander aircraft flight measurements . 15

5.4 Lockheed C130 flight vibration measurements . 16

5.5 Lockheed C130 landing shock measurements . 16

6 Inter data source comparison . 16

7 Environmental description . 17

7.1 Physical sources producing mechanical vibrations . 17

7.2 Environmental characteristics and severities . 19

7.3 Derived test severities . 19

8 Comparison with IEC 60721 (all parts) . 20

9 Recommendations . 23

Bibliography . 59

Figure 1 – Instrumentation locations for Britten-Norman Islander aircraft [1] . 24

Figure 2 – Instrumentation locations for BAe Jetstream aircraft [1] . 24

Figure 3 – Instrumentation locations for BAe HS 748 aircraft [1] . 25

Figure 4 – Instrumentation locations for Lockheed C130 Aircraft Islander [1] . 25

Figure 5 – Comparison of relative overall rms severities for different aircrafts [1] . 26

Figure 6 – Comparison of relative overall rms severities for various flight conditions [1] . 27

Figure 7 – Comparison of relative overall rms severities for various locations [1] . 28

Figure 8 – Typical cruise vibration spectrum for Britten-Norman Islander aircraft [1] . 29

Figure 9 – Typical cruise vibration spectrum for BAe Jetstream aircraft [1]. 29

Figure 10 – Typical cruise vibration spectrum for BAe HS 748 aircraft [1] . 30

Figure 11 – Typical cruise vibration spectrum for Lockheed C130 aircraft [1] . 30

Figure 12 – Britten-Norman Islander vibration at cabin during cruise [2] . 31

Figure 13 – Britten-Norman Islander vibration at plane of propeller during take-off [2] . 32

Figure 14 – Britten-Norman Islander vibration at middle of fuselage during take-off [2] . 32

Figure 15 – Britten-Norman Islander vibration at middle of fuselage during cruise [2] . 33

Figure 16 – Britten-Norman Islander vibration at rear of fuselage during cruise [2] . 33

Figure 17 – Comparison of vibration severities for Lockheed C130 – Take-off [3] . 34

Figure 18 – Comparison of vibration severities for Lockheed C130 – Climb [3]. 34

Figure 19 – Comparison of vibration severities for Lockheed C130 – Cruise [3] . 35

Figure 20 – Comparison of vibration severities for Lockheed C130 – Reverse thrust [3] . 35

Figure 21 – Comparison of vibration severities for Lockheed C130 at blade passing

frequency [3] . 36

Figure 22 – Comparison of vibration severities for Lockheed C130 background random

overall rms [3] . 37

Figure 23 – Lockheed C130 vibration at forward fuselage during take-off – Flight 3 [3] . 40

Figure 24 – Lockheed C130 vibration at forward fuselage (Frame 257) during cruise –

Flight 3 [3] . 40

Figure 25 – Lockheed C130 vibration at forward fuselage (Frame 317) during cruise –

Flight 3 [3] . 41

Figure 26 – Lockheed C130 vibration at aft fuselage during cruise – Flight 3 [3] . 41

Figure 27 – Lockheed C130 vibration at forward fuselage during landing – Flight 3 [3] . 42

Figure 28 – Lockheed C130 vibration at forward fuselage during take-off – Flight 4 [3] . 42

Figure 29 – Lockheed C130 vibration at plane of propeller during take-off – Flight 4 [3] . 43

Figure 30 – Lockheed C130 vibration at plane of propeller during climb – Flight 4 [3] . 43

Figure 31 – Lockheed C130 vibration at plane of propeller during cruise – Flight 4 [3] . 44

Figure 32 – Lockheed C130 vibration at plane of propeller during landing – Flight 4 [3] . 44

Figure 33 – Landing shocks from Lockheed C130 vertical [4] . 45

Figure 34 – Landing shocks from Lockheed C130 lateral [4] . 45

Figure 35 – Landing shocks from Lockheed C130 longitudinal [4] . 46

Figure 36 – Transall C160 vibration at fuselage floor during take-off [7] . 47

Figure 37 – Transall C160 vibration at fuselage floor during cruise [7] . 47

Figure 38 – Transall C160 vibration at fuselage floor during landing [7] . 48

Figure 39 – Lockheed C130J variant vibration at plane of propeller during cruise . 48

Figure 40 – Airbus A400M vibration on fuselage floor during cruise conditions . 49

Figure 41 – IEC 60721-3-2 [13] – Stationary vibration random severities . 49

Figure 42 – IEC TR 60721-4-2 [14] – Stationary vibration random severities . 50

Figure 43 – IEC 60721-3-2 [13] – Stationary vibration sinusoidal severities . 50

Figure 44 – IEC TR 60721-4-2 [14] – Stationary vibration sinusoidal severities . 51

Figure 45 – IEC 60721-3-2 [13] – Shock severities . 51

Figure 46 – IEC TR 60721-4-2 [14] – Shock severities for IEC 60068-2-29 [17] test

procedure . 52

Figure 47 – IEC TR 60721-4-2 [14] – Shock severities for IEC 60068-2-27 [15] test

procedure . 52

Figure 48 – Comparison of four propeller aircraft vibrations [1] with IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 53

Figure 49 – Comparison of Britten-Norman Islander aircraft vibrations [1] with

IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 53

Figure 50 – Comparison of Lockheed C130 aircraft vibrations [3] with IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 54

Figure 51 – Comparison of Transall C160 aircraft vibrations [7] with IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 54

Figure 52 – Comparison of Britten-Norman Islander aircraft cruise vibrations [1] with

IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 55

Figure 53 – Comparison of Britten-Norman Islander aircraft take-off/landing vibrations

[1] with IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 55

Figure 54 – Comparison of Lockheed C130 aircraft cruise vibrations [3] with

IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 56

– 4 – IEC TR 62131-6:2017 © IEC 2017

Figure 55 – Comparison of Lockheed C130 aircraft take-off/ landing vibrations [3] with

IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 56

Figure 56 – Comparison of Lockheed C130J variant cruise vibrations with

IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 57

Figure 57 – Comparison of Airbus A400M cruise vibrations with IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 57

Figure 58 – Comparison of Lockheed C130 landing shocks [4] with IEC 60721-3-2 [13] . 58

Table 1 – Record durations and error estimates for measured data for Britten-Norman

Islander aircraft flight measurements . 9

Table 2 – Record durations and error estimates for measured data for Lockheed C130

flight vibration measurements . 11

Table 3 – Overall rms severities for Britten-Norman Islander [2] . 31

Table 4 – Overall rms severities for Lockheed C130 – Flight 3 [3] . 38

Table 5 – Overall rms severities for Lockheed C130 – Flight 4 [3] . 39

Table 6 – Overall rms severities for Transall C160 [7] . 46

INTERNATIONAL ELECTROTECHNICAL COMMISSION

____________

ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS –

VIBRATION AND SHOCK OF ELECTROTECHNICAL EQUIPMENT –

Part 6: Transportation by propeller aircraft

FOREWORD

1) The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is a worldwide organization for standardization comprising

all national electrotechnical committees (IEC National Committees). The object of IEC is to promote

international co-operation on all questions concerning standardization in the electrical and electronic fields. To

this end and in addition to other activities, IEC publishes International Standards, Technical Specifications,

Technical Reports, Publicly Available Specifications (PAS) and Guides (hereafter referred to as “IEC

Publication(s)”). Their preparation is entrusted to technical committees; any IEC National Committee interested

in the subject dealt with may participate in this preparatory work. International, governmental and non-

governmental organizations liaising with the IEC also participate in this preparation. IEC collaborates closely

with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in accordance with conditions determined by

agreement between the two organizations.

2) The formal decisions or agreements of IEC on technical matters express, as nearly as possible, an international

consensus of opinion on the relevant subjects since each technical committee has representation from all

interested IEC National Committees.

3) IEC Publications have the form of recommendations for international use and are accepted by IEC National

Committees in that sense. While all reasonable efforts are made to ensure that the technical content of IEC

Publications is accurate, IEC cannot be held responsible for the way in which they are used or for any

misinterpretation by any end user.

4) In order to promote international uniformity, IEC National Committees undertake to apply IEC Publications

transparently to the maximum extent possible in their national and regional publications. Any divergence

between any IEC Publication and the corresponding national or regional publication shall be clearly indicated in

the latter.

5) IEC itself does not provide any attestation of conformity. Independent certification bodies provide conformity

assessment services and, in some areas, access to IEC marks of conformity. IEC is not responsible for any

services carried out by independent certification bodies.

6) All users should ensure that they have the latest edition of this publication.

7) No liability shall attach to IEC or its directors, employees, servants or agents including individual experts and

members of its technical committees and IEC National Committees for any personal injury, property damage or

other damage of any nature whatsoever, whether direct or indirect, or for costs (including legal fees) and

expenses arising out of the publication, use of, or reliance upon, this IEC Publication or any other IEC

Publications.

8) Attention is drawn to the Normative references cited in this publication. Use of the referenced publications is

indispensable for the correct application of this publication.

9) Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this IEC Publication may be the subject of

patent rights. IEC shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

The main task of IEC technical committees is to prepare International Standards. However, a

technical committee may propose the publication of a Technical Report when it has collected

data of a different kind from that which is normally published as an International Standard, for

example "state of the art".

IEC TR 62131-6, which is a Technical Report, has been prepared by IEC technical committee

104: Environmental conditions, classification and methods of test.

– 6 – IEC TR 62131-6:2017 © IEC 2017

The text of this technical report is based on the following documents:

Enquiry draft Report on voting

104/687A/DTR 104/744/RVDTR

Full information on the voting for the approval of this Technical Report can be found in the

report on voting indicated in the above table.

This document has been drafted in accordance with the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

A list of all parts in the IEC 62131 series, published under the general title Environmental

conditions – Vibration and shock of electrotechnical equipment, can be found on the IEC

website.

The committee has decided that the contents of this document will remain unchanged until the

stability date indicated on the IEC website under "http://webstore.iec.ch" in the data related to

the specific document. At this date, the document will be

• reconfirmed,

• withdrawn,

• replaced by a revised edition, or

• amended.

A bilingual version of this publication may be issued at a later date.

IMPORTANT – The 'colour inside' logo on the cover page of this publication indicates

that it contains colours which are considered to be useful for the correct

understanding of its contents. Users should therefore print this document using a

colour printer.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS –

VIBRATION AND SHOCK OF ELECTROTECHNICAL EQUIPMENT –

Part 6: Transportation by propeller aircraft

1 Scope

This part of IEC 62131 reviews the available dynamic data relating to the transportation of

electrotechnical equipment. The intent is that from all the available data an environmental

description will be generated and compared to that set out in IEC 60721 (all parts)[11] .

For each of the sources identified the quality of the data is reviewed and checked for self

consistency. The process used to undertake this check of data quality and that used to

intrinsically categorize the various data sources is set out in IEC TR 62131-1[18].

This document primarily addresses data extracted from a number of different sources for

which reasonable confidence exist in its quality and validity. The report also reviews some

data for which the quality and validity cannot realistically be verified. These data are included

to facilitate validation of information from other sources. The document clearly indicates when

utilizing information in this latter category.

This document addresses data from a number of data gathering exercises. The quantity and

quality of data in these exercises varies considerably as does the range of conditions

encompassed.

Not all of the data reviewed were made available in electronic form. To permit comparison to

be made, in this assessment, a quantity of the original (non-electronic) data has been

manually digitized.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references in this document.

3 Terms and definitions

No terms and definitions are listed in this document.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following

addresses:

• IEC Electropedia: available at http://www.electropedia.org/

• ISO Online browsing platform: available at http://www.iso.org/obp

___________

References in square brackets refer to the Bibliography.

– 8 – IEC TR 62131-6:2017 © IEC 2017

4 Data source and quality

4.1 Vibration survey of four different propeller driven aircraft

Work was undertaken in 1989 to compare the source vibration on four different propeller

driven aircraft (see [1]). This comparison work was undertaken to establish base data for a

guidance chapter on propeller aircraft vibrations.

The four aircraft types encompassed by the vibration survey were: Britten-Norman Islander,

BAe Jet Stream 100, BAe HS 748 and the Lockheed (Hercules) C130 . The data from the first

three aircraft types were specifically collected for this comparison exercise during 1988.

However, the data for the Lockheed C130 originates from several flights undertaken for

another purpose during 1985. This Lockheed C130 data has commonality with other data

referred to in this document. Information on each of the four aircraft is set out below:

– The Britten-Norman Islander is a lightweight twin engine aircraft fitted with reciprocating

engines driving twin-bladed variable pitch propellers. With this arrangement different

power settings can be achieved by varying both engine speed and propeller pitch. The

general arrangement of the aircraft is shown in Figure 1.

– The BAe Jetstream 100 is a light utility transport aircraft fitted with twin, constant speed

turbo-prop engines each driving a three bladed variable pitch propeller. With a fixed shaft

rotational frequency of approximately 30 Hz, the blade passing frequency (shaft speed

times the number of propeller blades) for this aircraft is fixed at approximately 90 Hz. The

general arrangement of the aircraft is shown in Figure 2.

– The BAe HS 748 is a regional transport aircraft driven by twin turbo-prop engines fitted

with four bladed variable pitch propellers. As the engines are variable speed, different

power settings can be achieved by varying both engine speed and propeller pitch. For

cruise conditions the propeller shaft rotational frequency is typically around 22 Hz, giving

a blade passing frequency of around 88 Hz. The general arrangement of the aircraft is

shown in Figure 3. This particular aircraft was fitted in a fire fighting configuration and this

could be expected to give rise to increased vibration due to the presence of the large

water tanks located externally under the fuselage.

– The Lockheed C130 Mk 1 aircraft, encompassed by this exercise, is a large transport

aircraft driven by four fixed speed turbo-prop engines each powering a four bladed

variable pitch propeller. The propeller shaft rotational speed is approximately 17 Hz

producing a blade passing frequency of approximately 68 Hz. The general arrangement of

the aircraft is shown in Figure 4.

The measurements on all four aircrafts used the same flight instrumentation. This comprised

twelve piezo-electric accelerometers and associated charge amplifiers. The vibration

measurements were recorded on a 14 channel FM recorder. The system provided an effective

measurement frequency range of 4 Hz to 2 500 Hz. The accelerometers were arranged in four

tri-axial groups placed in the forward, centre and aft regions of the aircraft. The fourth

transducer group was placed in the plane of the propeller disc. All the transducers were

internally mounted on relatively stiff airframe locations.

Measurements were made for extended periods during the flight; the periods encompassed

take-off, climb, cruise, descent, landing and taxi. The take-off phase included bringing the

engines to full power, immediately before it started the take-off run. The landing phase

included the use of reverse thrust, if that was appropriate. All the take-off and landings

occurred on paved concrete runways of good length. That is no short take-off or landing

conditions were considered.

___________

Britten-Norman Islander, BAe Jet Stream 100, BAe HS 748 and Lockheed (Hercules) C130 are the trade names

of products supplied by Britten-Norman, BAE Systems and Lockheed Martin respectively. This information is

given for the convenience of users of this document and does not constitute an endorsement by IEC of the

products named.

The original analysis was mostly in the form of acceleration power spectral densities (PSDs),

although very few of these are presented in the report. The report does not indicate the record

duration used for the power spectral density analysis, but durations used by the agency, who

made these measurements, are typically better than 30 s. The analysis frequency bandwidth

was typically a little under 3 Hz. Whilst this is adequate to describe the broadband

background vibration induced by propeller aircraft, it is inadequate to quantify, in terms of

power spectral density amplitude, the tones arising from the propeller shaft, the blade passing

frequency and the associated harmonics. The report indicates that peak hold spectra were

used to estimate amplitudes at rotor and blade passing frequencies. However, the usual

approach used by this measurement agency, in such circumstances, was to compute the tonal

component root mean square (rms) by integration of the power spectral density amplitudes for

each tonal component. The method used to quantify the vibration amplitudes at the propeller

shaft, blade passing frequency and their harmonics, is a particular data analysis issue

encountered when addressing propeller aircraft vibration data.

The report compares relative severities of the four aircraft in terms of overall rms for the

different aircraft (Figure 5), flight conditions (Figure 6) and location within the aircraft (Figure

7). All these comparisons are in terms of relative amplitude i.e. they are all scaled such that

the largest amplitude is to unity. The report also presents typical cruise power spectral

densities for each aircraft type (Figure 8 to Figure 11).

Although the information in this document is limited, the quality of the information is

reasonable and meets the required validation criteria for data quality (single data item).

4.2 Britten-Norman Islander aircraft flight measurements

Work was undertaken in 1988 to establish the vibration severities of a Britten-Norman

Islander aircraft. The data from this measurement exercise was used within the comparison of

the previous data set. This document contains analysis of the entire measured data.

The measurement locations are as set out in the review of the previous data set and shown in

Figure 1 viz. tri-axial accelerometers on the floor of the cockpit, on the floor of the fuselage in

the plane of the propeller, on the floor in the centre of the fuselage and on the floor at the aft

fuselage. The flight conditions during which measurements were made comprised: take-off,

climb, left turn, long left turn at cruise speed and at an altitude of 500 ft (152 m), straight and

level at cruise speed at an altitude of 500 ft (152 m), descent and landing approach and

landing.

The data is presented in the form of acceleration power spectral densities (PSDs) for each

accelerometer at each of the seven flight conditions (84 plots in total). The report indicates

the record duration used for each power spectral density analysis and analysis frequency

bandwidth utilized, which are tabulated below (see Table 1).

Table 1 – Record durations and error estimates for measured data

for Britten-Norman Islander aircraft flight measurements

Flight event Analysis Measurement Random error

frequency duration

bandwidth

Hz s %

Take-off 3,014 30 10

Climb 3,014 35 9,7

Left turn 3,014 60 7,4

Long left turn at cruise speed and 500 ft 3,014 75 6,6

Straight and level at cruise speed at 500 ft 3,014 175 4,3

Landing approach 3,014 30 10

Landing 3,014 15 15

– 10 – IEC TR 62131-6:2017 © IEC 2017

The report does not separately quantify the tones arising from the propeller shaft, blade

passing frequency or the associated harmonics tones. Although these are clearly identified in

the analysis, the frequency they occur at is not fixed as the engine speed and propeller shaft

speed varies.

The overall root mean square values (3 Hz to 2 000 Hz) for each accelerometer at each of the

seven flight conditions are presented in Table 3. Selected power spectral densities are

presented in Figure 12 to Figure 16. Inspection of the power spectral densities presented in

the report indicates that the events have a spectral characteristic which would be expected

from variable speed engine propeller aircraft. That is, the shaft and blade passing

components occur at different centre frequencies for different flight conditions. With that said,

the landing measurements indicate unusual characteristics, which do not appear to represent

vibration conditions (they are more representative of shock conditions). For that reason the

power spectral density for the landing event are not included here. The landing approach

measurements are included as they mostly appear to be composed of vibration. However, the

shape of the power spectral density is not entirely consistent with the other flight conditions.

The report only presents analysed data in the form of acceleration power spectral densities.

The majority of these appear to have characteristics that would be expected from propeller

aircraft. However, this is not the case for the information for the landing event. With this

caveat the quality of the information is reasonable and meets the required validation criteria

for data quality (single data item).

4.3 Lockheed C130 flight vibration measurements

This large transport aircraft is extensively used in military and civil transport applications and

has been in-service for over four decades. The majority of the C130 aircraft fleet is used to

transport cargo and can be considered to put utility above passenger comfort. As such the

vibrations are generally at a level which would be unacceptable to the majority of civilian

passengers. The vibration characteristics and severities from this aircraft are those used by a

variety of international and national standards, to set the vibration test requirements for

propeller aircraft equipment. As a consequence it is not surprising that, over the years, a

variety of vibration measurement exercises have been undertaken on the aircraft. Although

several measurement exercises on the C130 were considered for this work, the majority of the

data presented are from measurement work undertaken by one agency. That work

encompassed measurements undertaken over several decades on a number of different

airframes and aircraft build standards. The measurement work reported was specifically

undertaken to establish the source vibration on the fleet of the Lockheed C130 aircraft

operated by the UK military forces (see [3]). This work was undertaken specifically to

establish payload cabin floor vibration data for use in establishing test severities for the UK

military standard relating to environmental testing requirements.

The various Lockheed C130 aircraft, encompassed by this exercise, were all UK military

aircraft used for a variety of roles, including peace keeping and disaster relief operations. The

general arrangement of the aircraft is shown in Figure 4. The vast majority of the worldwide

fleet of C130 aircraft (and all the C130 aircraft encompassed by this document), utilize a four

bladed straight propeller with a shaft rotational speed of approximately 17 Hz. This results in

a characteristic blade passing frequency of 68 Hz. However, a recent variant of this aircraft

replaced the four bladed straight propellers with six bladed propellers of a curved design. This

results in a blade passing frequency of 102 Hz.

The various measurement exercises reported here for the C130, used essentially the same

measurement locations and essentially the same flight instrumentation. The measurement

instrumentation comprised 12 piezo-electric accelerometers and associated charge amplifiers

which were recorded on an FM analogue recorder. The system provided an effective

measurement frequency range of 4 Hz to 2 500 Hz. The accelerometers were arranged mostly

in tri-axial groups placed in the cargo bay of the aircraft. In some cases axial (aircraft fore/aft)

measurements were omitted. All the transducers were internally mounted on relatively stiff

airframe locations, usually at aircraft frame locations.

In some of the flights reported here, additional measurements were made on two large

containers with the transducers located on the pallet adjacent to the container/floor interface

(i.e. as far as practicable measuring the vibration inputs to the containers). The two

containers were over 2 000 kg in mass and approximately 1,5 m wide and 3,0 m long. They

were positioned one behind the other in the aircraft cargo bay, together occupying the

majority of the central zone of the aircraft. The two measurement locations were positioned at

the aft port location of the aft container and the forward starboard location of the forward

container. As such the measurements spanned the total length of the two containers. For

these more recent measurements the FM analogue recorder was replaced with a digital

recorder.

Measurements were made for statistically reasonable periods, generally in excess of 30 s,

during the flight and encompassed take-off, climb, cruise, descent, landing and taxi. The

take-off phase included the period necessary to bring the engines to full power immediately

before the start of the take-off run. The landing phase included the use of reverse thrust. All

the take-off and landings measured were on adequate length good quality concrete paved

runways.

The analysis was mostly in the form of acceleration power spectral densities (PSDs), although

a certain amount of peak hold analysis was also undertaken. The data reports include a

statement of the measurement record duration and bandwidth for the power spectral density

analysis. As such, random error can be established for each analysis and the appropriate

values are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 – Record durations and error estimates for measured data

for Lockheed C130 flight vibration measurements

Flight 3 event Duration Random Flight 4 event Duration Random

error error

s % s %

Pre-flight taxi 30 11 Full power run 10 18

Take-off 30 11 Take-off 20 13

Climb 60 8 Climb 80 7

Cruise and turns 40 9 Cruise 60 8

Descent 40 9 Descent 160 5

Landing approach 40 9 Landing approach 60 8

Landing 30 11 Landing 20 13

The analysis frequency bandwidth was typically a little under 3 Hz. This is adequate to

describe the broadband background vibration induced by propeller aircraft. However, this

analysis bandwidth is not really adequate to quantify the tones arising from the propeller

shaft, blade passing frequency and the associated harmonics. In this case peak hold spectra

were used to give a more reliable estimate of the amplitudes at the blade passing tones

during transitory conditions. Specifically, the amplitudes of the tonal peaks were quantified

from the peak hold values by assuming they represent sinusoidal tones in the analysis

bandwidth. Provided the tones remain stationary in a single analysis band, the derived tonal

values accurately represent the largest value occurring over the duration of the record,

averaged over blocks of approximately 0,4 s duration.

Figure 17 to Figure 20 compare the tonal peak amplitudes for the vibration components at

engine shaft frequency, first propeller blade passing frequency and the subsequent two

harmonics of blade passing frequency. These comparisons are made for three locations

(forward, middle and aft) of the cargo bay and are presented separately for take-off, climb,

cruise and landing (specifically the use of reverse thrust). Figure 21 shows the peak tonal

value for the blade passing frequency for a range of flight conditions for which measurements

are available. Figure 22 shows similar information but for the overall vibration root mean

square acquired between 3 Hz and 2 000 Hz. Figure 23 to Figure 32 present selected

– 12 – IEC TR 62131-6:2017 © IEC 2017

acceleration power spectral densities for different locations and flight conditions from two

flights (designated here flights 3 and 4). These two flights used different, but overlapping,

measurement locations. Table 4 and Table 5 show the actual overall vibration root mean

square values from these two flights for all measurement locations and flight conditions for

which data are available.

The information in this document has some limitations but it does encompass the main cargo

hold of the Lockheed C130 aircraft. The quality of the information is reasonable and meets the

required validation criteria for data quality (single data item).

4.4 Lockheed C130 landing shock measurements

Work undertaken in 1988 reviewed landing shock measurements from four flights of a

Lockheed C130 aircraft (see [4]). This work was primarily undertaken to establish cabin floor

shock severities for the UK military standard relating to environmental testing requirements.

The measurement exercise included both normal and short landings. The latter were included

because this propeller aircraft is able to use short and temporary runways at remote locations.

The landing shocks arising from such use is typically more severe than would be the case for

normal landings. Indeed this measurement exercise arose partly because a payload carried

by a C130 aircraft (and some of the aircraft equipment) had been damaged as a result of a

short landing on a temporary runway during disaster relief activities.

The Lockheed C130 Mk 1 aircraft, encompassed by this exercise, is that utilized and

described in 4.3. The measurements used flight instrumentation comprising six piezo-electric

accelerometers and associated charge amplifiers which were recorded on a 14 channel FM

recorder. The system provided an effective measurement frequency range of 2 Hz to 250 Hz

with a subsequent acquisition rate of 1 000 sample per second (sps). The accelerometers

were arranged in two tri-axial groups; one placed at aft port location of one container, the

other at forward starboard location of a second container (see 4.3 for specific information on

the containers). Measurements were made throughout the landing phase with the touch down

event specifically extracted for shock analysis.

The analysis was in the form of time histories (which are not suitable for reproduction here)

and shock response spectra (SRS). The time histories used for the shock response spectrum

calculations were of approximately 1 s duration and adopted a resonant gain (Q) of 16,66 to

facilitate comparison with some historic US data.

The report contains time history and the shock response spectra from four flights,

five landings and from the six measurement channels. Within these data, the third flight

contained one tactical landing and one normal landing. The remaining flights were all normal

landings. Figure 33 to Figure 35 show the shock response spectra from all four flights for the

aircraft vertical, lateral and longitudinal axes.

Although the information in this document is limited in quantity and frequency range, the

quality of the information is reasonable and meets the required validation criteria for data

quality (single data item).

4.5 Supplementary data

The supplementary data, detailed below, comprises information arising from reputable

sources, but for which the data quality could not be adequately verified.

The SRETS study (see [5]) was undertaken during 1998 and reviewed both measured data

sources and test severities for a variety of methods of transportation. It compared two

measured data sets related to propeller aircraft. One of those data sets is from the UK

defence standard DEF STAN 00-35 [6], but that data set is already included in this document.

The second data set was from the French military standard GAM-EG-13 [7]. That standard

includes information from the Transall C-160 aircraft. The Transall C-160 is a heavy

transport aircraft (approximately 50 000 kg) powered by two turboprop engines each driving a

four-bladed propeller. The measured information included in GAM-EG-13 relates to two

ground and seven flight conditions. The measurements are from only one fuselage floor

location and the specific location is not stated. The measured information is presented in the

form of acceleration power spectral densities for take-off, cruise and landing, which are

included here as Figure 36, Figure 37 and Figure 38 respectively. Overall root mean square

vibration severities are also presented, listed here in Table 6, and are assumed to be over the

frequency range 1 Hz to 1 500 Hz. These overall root mean square values are lower than for

the other aircraft included in this document, but not unreasonably so. The power spectral

densities indicate that the blade passing tone is dominant and the frequency of the tone

appears to vary between 45 Hz to 55 Hz.

As part of an exercise, in the early 1970’s, to authenticate test severities for the US military

specification MIL STD 810[23], J.T. Foley [8] at the US Sandia National Laboratories

undertook an extensive exercise to establish transportation severities on a number of

platforms including two propeller aircraft i.e. the Lockheed C130 and the (now obsolete)

Douglas C133. Unfortunately, the analysis process used by Foley throughout his work is

relatively unique and not directly comparable with the information presented in this document.

Nevertheless, the information generated by Foley seems to be largely consistent with that

already reviewed in this document.

As already indicated a number of test standards adopt a shaped random profile, which seem

to be mostly based upon the vibration characteristics of the Lockheed C130. One standard

that differ

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...