ISO 4259:2006

(Main)Petroleum products — Determination and application of precision data in relation to methods of test

Petroleum products — Determination and application of precision data in relation to methods of test

ISO 4259:2006 covers the calculation of precision estimates and their application to specifications. In particular, it contains definitions of relevant statistical terms, the procedures to be adopted in the planning of an inter-laboratory test programme to determine the precision of a test method, the method of calculating the precision from the results of such a programme, and the procedure to be followed in the interpretation of laboratory results in relation both to precision of the test methods and to the limits laid down in specifications. The procedures in ISO 4259:2006 have been designed specifically for petroleum and petroleum-related products, which are normally homogeneous. However, the procedures described in this International Standard can also be applied to other types of homogeneous products. Careful investigations are necessary before applying ISO 4259:2006 to products for which the assumption of homogeneity can be questioned.

Produits pétroliers — Détermination et application des valeurs de fidélité relatives aux méthodes d'essai

L'ISO 4259:2006 traite du calcul des estimations de fidélité et de leur application aux spécifications. En particulier, elle contient les définitions des termes statistiques concernés, les procédures à suivre dans l'organisation d'un programme d'essai interlaboratoires destiné à déterminer la fidélité d'une méthode d'essai, la méthode de calcul de la fidélité à partir des résultats d'un tel programme et la procédure à suivre dans l'interprétation des résultats de laboratoire, à la lumière de la fidélité des méthodes de test et des limites fixées dans les spécifications. Les procédures de l'ISO 4259:2006 ont été conçues spécifiquement pour les produits pétroliers et leurs produits connexes, qui sont normalement homogènes. Cependant on reconnaît que les procédures décrites dans l'ISO 4259:2006 peuvent aussi s'appliquer à d'autres types de produits homogènes. Des contrôles attentifs s'avèrent nécessaires avant d'appliquer l'ISO 4259:2006 à des produits pour lesquels la présomption d'homogénéité peut être mise en question.

General Information

- Status

- Withdrawn

- Publication Date

- 27-Jul-2006

- Withdrawal Date

- 27-Jul-2006

- Current Stage

- 9599 - Withdrawal of International Standard

- Start Date

- 01-Nov-2017

- Completion Date

- 12-Feb-2026

Relations

- Effective Date

- 12-Feb-2026

- Effective Date

- 28-Feb-2023

- Effective Date

- 06-Jun-2022

- Effective Date

- 09-Nov-2013

- Effective Date

- 09-Nov-2013

- Effective Date

- 12-May-2008

- Effective Date

- 15-Apr-2008

- Effective Date

- 15-Apr-2008

ISO 4259:2006 - Petroleum products -- Determination and application of precision data in relation to methods of test

ISO 4259:2006 - Produits pétroliers -- Détermination et application des valeurs de fidélité relatives aux méthodes d'essai

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

ABS Quality Evaluations Inc.

American Bureau of Shipping quality certification.

Element Materials Technology

Materials testing and product certification.

ABS Group Brazil

ABS Group certification services in Brazil.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO 4259:2006 is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Petroleum products — Determination and application of precision data in relation to methods of test". This standard covers: ISO 4259:2006 covers the calculation of precision estimates and their application to specifications. In particular, it contains definitions of relevant statistical terms, the procedures to be adopted in the planning of an inter-laboratory test programme to determine the precision of a test method, the method of calculating the precision from the results of such a programme, and the procedure to be followed in the interpretation of laboratory results in relation both to precision of the test methods and to the limits laid down in specifications. The procedures in ISO 4259:2006 have been designed specifically for petroleum and petroleum-related products, which are normally homogeneous. However, the procedures described in this International Standard can also be applied to other types of homogeneous products. Careful investigations are necessary before applying ISO 4259:2006 to products for which the assumption of homogeneity can be questioned.

ISO 4259:2006 covers the calculation of precision estimates and their application to specifications. In particular, it contains definitions of relevant statistical terms, the procedures to be adopted in the planning of an inter-laboratory test programme to determine the precision of a test method, the method of calculating the precision from the results of such a programme, and the procedure to be followed in the interpretation of laboratory results in relation both to precision of the test methods and to the limits laid down in specifications. The procedures in ISO 4259:2006 have been designed specifically for petroleum and petroleum-related products, which are normally homogeneous. However, the procedures described in this International Standard can also be applied to other types of homogeneous products. Careful investigations are necessary before applying ISO 4259:2006 to products for which the assumption of homogeneity can be questioned.

ISO 4259:2006 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 75.080 - Petroleum products in general. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO 4259:2006 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to EN ISO 4259:2006, ISO/R 1161:1970, ISO 4210-2:2014, ISO 4259-1:2017, ISO 4259-2:2017, SIST ISO 4259:1996, ISO 4259:1992, ISO 4259:1992/Cor 1:1993. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

ISO 4259:2006 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 4259

Third edition

2006-08-01

Petroleum products — Determination and

application of precision data in relation to

methods of test

Produits pétroliers — Détermination et application des valeurs de

fidélité relatives aux méthodes d'essai

Reference number

©

ISO 2006

PDF disclaimer

This PDF file may contain embedded typefaces. In accordance with Adobe's licensing policy, this file may be printed or viewed but

shall not be edited unless the typefaces which are embedded are licensed to and installed on the computer performing the editing. In

downloading this file, parties accept therein the responsibility of not infringing Adobe's licensing policy. The ISO Central Secretariat

accepts no liability in this area.

Adobe is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated.

Details of the software products used to create this PDF file can be found in the General Info relative to the file; the PDF-creation

parameters were optimized for printing. Every care has been taken to ensure that the file is suitable for use by ISO member bodies. In

the unlikely event that a problem relating to it is found, please inform the Central Secretariat at the address given below.

© ISO 2006

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from either ISO at the address below or

ISO's member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO 2006 – All rights reserved

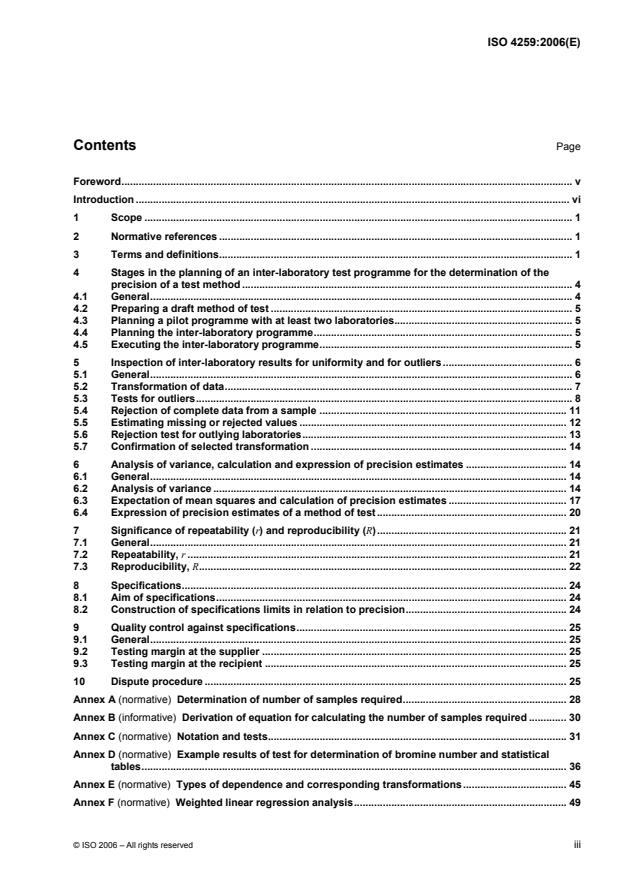

Contents Page

Foreword. v

Introduction . vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions. 1

4 Stages in the planning of an inter-laboratory test programme for the determination of the

precision of a test method . 4

4.1 General. 4

4.2 Preparing a draft method of test . 5

4.3 Planning a pilot programme with at least two laboratories. 5

4.4 Planning the inter-laboratory programme. 5

4.5 Executing the inter-laboratory programme.5

5 Inspection of inter-laboratory results for uniformity and for outliers . 6

5.1 General. 6

5.2 Transformation of data. 7

5.3 Tests for outliers. 8

5.4 Rejection of complete data from a sample . 11

5.5 Estimating missing or rejected values . 12

5.6 Rejection test for outlying laboratories. 13

5.7 Confirmation of selected transformation .14

6 Analysis of variance, calculation and expression of precision estimates . 14

6.1 General. 14

6.2 Analysis of variance . 14

6.3 Expectation of mean squares and calculation of precision estimates . 17

6.4 Expression of precision estimates of a method of test. 20

7 Significance of repeatability (r) and reproducibility (R). 21

7.1 General. 21

7.2 Repeatability, r . 21

7.3 Reproducibility, R.22

8 Specifications. 24

8.1 Aim of specifications. 24

8.2 Construction of specifications limits in relation to precision. 24

9 Quality control against specifications. 25

9.1 General. 25

9.2 Testing margin at the supplier . 25

9.3 Testing margin at the recipient . 25

10 Dispute procedure . 25

Annex A (normative) Determination of number of samples required. 28

Annex B (informative) Derivation of equation for calculating the number of samples required . 30

Annex C (normative) Notation and tests. 31

Annex D (normative) Example results of test for determination of bromine number and statistical

tables. 36

Annex E (normative) Types of dependence and corresponding transformations. 45

Annex F (normative) Weighted linear regression analysis. 49

Annex G (normative) Rules for rounding off results . 56

Annex H (informative) Explanation of equations given in Clause 7 . 57

Annex I (informative) Specifications that relate to a specified degree of criticality. 59

Bibliography . 62

iv © ISO 2006 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies

(ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through ISO

technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical committee has been

established has the right to be represented on that committee. International organizations, governmental and

non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work. ISO collaborates closely with the

International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of electrotechnical standardization.

International Standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

The main task of technical committees is to prepare International Standards. Draft International Standards

adopted by the technical committees are circulated to the member bodies for voting. Publication as an

International Standard requires approval by at least 75 % of the member bodies casting a vote.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of patent

rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

ISO 4259 was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 28, Petroleum products and lubricants.

This third edition cancels and replaces the second edition (ISO 4259:1992), Clauses 1, 5, 7 C.7, E.2 and F.3

and subclauses 4.2, 5.2, 6.3.2, 6.3.3.1, 6.3.3.3, 6.4, 8.2, 10.2, 10.4 and 10.5, which have been technically

revised. It also incorporates the Technical Corrigendum ISO 4259:1992/Cor.1:1993.

Introduction

For purposes of quality control and to check compliance with specifications, the properties of commercial

petroleum products are assessed by standard laboratory test methods. Two or more measurements of the

same property of a specific sample by any given test method do not usually give exactly the same result. It is,

therefore, necessary to take proper account of this fact, by arriving at statistically-based estimates of the

precision for a method, i.e. an objective measure of the degree of agreement expected between two or more

results obtained in specified circumstances.

[11]

ISO 4259 makes reference to ISO 3534-2 , which gives a different definition of true value (see 3.26).

ISO 4259 also refers to ISO 5725-2. The latter is required in particular and unusual circumstances (see 5.2)

for the purpose of estimating precision.

vi © ISO 2006 – All rights reserved

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 4259:2006(E)

Petroleum products — Determination and application of

precision data in relation to methods of test

1 Scope

This International Standard covers the calculation of precision estimates and their application to specifications.

In particular, it contains definitions of relevant statistical terms (Clause 3), the procedures to be adopted in the

planning of an inter-laboratory test programme to determine the precision of a test method (Clause 4), the

method of calculating the precision from the results of such a programme (Clauses 5 and 6), and the

procedure to be followed in the interpretation of laboratory results in relation both to precision of the test

methods and to the limits laid down in specifications (Clauses 7 to 10).

The procedures in this International Standard have been designed specifically for petroleum and petroleum-

related products, which are normally homogeneous. However, the procedures described in this International

Standard can also be applied to other types of homogeneous products. Careful investigations are necessary

before applying this International Standard to products for which the assumption of homogeneity can be

questioned.

2 Normative references

The following referenced documents are indispensable for the application of this document. For dated

references, only the edition cited applies. For undated references, the latest edition of the referenced

document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 5725-2:1994, Accuracy (trueness and precision) of measurement methods and results — Part 2: Basic

method for the determination of repeatability and reproducibility of a standard measurement method

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

3.1

analysis of variance

technique that enables the total variance of a method to be broken down into its component factors

3.2

between-laboratory variance

element of the total variance attributable to the difference between the mean values of different laboratories

NOTE 1 When results obtained by more than one laboratory are compared, the scatter is usually wider than when the

same number of tests are carried out by a single laboratory, and there is some variation between means obtained by

different laboratories. These give rise to the between-laboratory variance which is that component of the overall variance

due to the difference in the mean values obtained by different laboratories.

NOTE 2 There is a corresponding definition for between-operator variance.

NOTE 3 The term “between-laboratory” is often shortened to “laboratory” when used to qualify representative

parameters of the dispersion of the population of results, for example as “laboratory variance”.

3.3

bias

difference between the true value (related to the method of test) and the known value, where this is available

NOTE For a definition of “true value” and “known value,” see 3.26 and 3.8, respectively.

3.4

blind coding

assignment of a different number to each sample so that no other identification or information on any sample

is given to the operator

3.5

check sample

sample taken at the place where the product is exchanged, i.e. where the responsibility for the product quality

passes from the supplier to the recipient

3.6

degrees of freedom

divisor used in the calculation of variance; one less than the number of independent results

NOTE The definition applies strictly only in the simplest cases. Complete definitions are beyond the scope of this

International Standard.

3.7

determination

process of carrying out the series of operations specified in the test method, whereby a single value is

obtained

3.8

known value

actual quantitative value implied by the preparation of the sample

NOTE The known value does not always exist, for example for empirical tests such as flash point.

3.9

mean

arithmetic mean

sum of the results divided by their number for a given set of results

3.10

mean square

sum of squares divided by the degrees of freedom

3.11

normal distribution

probability distribution of a continuous random variable, x, such that, if x is any real number, the probability

density is

⎡⎤

11 x − µ

⎛⎞

⎢⎥

fx=−exp ,−∞

()

⎜⎟

2 σ

σ 2π⎢⎥⎝⎠

⎣⎦

NOTE µ is the true value and σ is the standard deviation of the normal distribution (σ > 0).

3.12

operator

person who normally and regularly carries out a particular test

2 © ISO 2006 – All rights reserved

3.13

outlier

result far enough in magnitude from other results to be considered not a part of the set

3.14

precision

closeness of agreement between the results obtained by applying the experimental procedure several times

on identical materials and under prescribed conditions

NOTE The smaller the random part of the experimental error, the more precise is the procedure.

3.15

random error

chance variation encountered in all test work despite the closest control of variables

3.16

recipient

any individual or organization who receives or accepts the product delivered by the supplier

3.17

repeatability

〈qualitatively〉 closeness of agreement between independent results obtained in the normal and correct

operation of the same method on identical test material, in a short interval of time, and under the same test

conditions (same operator, same apparatus, same laboratory)

NOTE The representative parameters of the dispersion of the population that can be associated with the results are

qualified by the term “repeatability”, for example, repeatability standard deviation or repeatability variance. It is important

that the term “repeatability” not be confused with the terms “between repeats” or “repeats” when used in this way (see

3.19). Repeatability refers to the state of minimum random variability of results. The period of time during which repeated

results are to be obtained should therefore be short enough to exclude time-dependent errors, for example, environmental

and calibration errors.

3.18

repeatability

〈quantitatively〉 value equal to or below which the absolute difference between two single test results obtained

in the conditions specified that can be expected to lie with a probability of 95 %

NOTE For the details of the conditions specified, see 3.17.

3.19

replication

execution of a test method more than once so as to improve precision and to obtain a better estimation of

testing error

NOTE Replication should be distinguished from repetition in that the former implies that repeated experiments are

carried out at one place and, as far as possible, within one period of time. The representative parameters of the dispersion

of the population that can be associated with repeated experiments are qualified by the term “between repeats”, or in

shortened form “repeats”, for example, “repeats standard deviation”.

3.20

reproducibility

〈qualitatively〉 closeness of agreement between individual results obtained in the normal and correct operation

of the same method on identical test material but under different test conditions (different operators, different

apparatus and different laboratories)

NOTE The representative parameters of the dispersion of the population that can be associated with the results are

qualified by the term “reproducibility”, for example, reproducibility standard deviation or reproducibility variance.

3.21

reproducibility

〈quantitatively〉 value equal to or below which the absolute difference between two single test results on

identical material obtained by operators in different laboratories, using the standardized test method, may be

expected to lie with a probability of 95 %

3.22

result

final value obtained by following the complete set of instructions in the test method; it may be obtained from a

single determination or from several determinations depending on the instructions in the method

NOTE It is assumed that the result is rounded off according to the procedure specified in Annex G.

3.23

standard deviation

measure of the dispersion of a series of results around their mean, equal to the positive square root of the

variance and estimated by the positive square root of the mean square

3.24

sum of squares

sum of squares of the differences between a series of results and their mean

3.25

supplier

any individual or organization responsible for the quality of a product just before it is taken over by the

recipient

3.26

true value

for practical purposes, the value towards which the average of single results obtained by n laboratories tends,

as n tends towards infinity

NOTE 1 Such a true value is associated with the particular method of test.

[11]

NOTE 2 A different and idealized definition is given in ISO 3534-2 .

3.27

variance

mean of the squares of the deviation of a random variable from its mean, estimated by the mean square

4 Stages in the planning of an inter-laboratory test programme for the

determination of the precision of a test method

4.1 General

The stages in planning an inter-laboratory test programme are as follows:

a) preparing a draft method of test;

b) planning a pilot programme with at least two laboratories;

c) planning the inter-laboratory programme;

d) executing the inter-laboratory programme.

The four stages are described in turn in 4.2 to 4.5.

4 © ISO 2006 – All rights reserved

4.2 Preparing a draft method of test

This shall contain all the necessary details for carrying out the test and reporting the results. Any condition that

could alter the results shall be specified.

A clause on precision is included in the draft method of the test at this stage only as a heading. It is

recommended that the lower limit of the scope of the test method is not less than the region of the lowest

value tested in the inter-laboratory programme, and is at least 2R greater than the lowest achievable result

(see 8.2), where R is the reproducibility estimate. Similarly, it is recommended that the upper limit of the scope

of a test method is not greater than the region of the highest value tested in the inter-laboratory programme,

and is at least 2R less than the highest achievable result.

4.3 Planning a pilot programme with at least two laboratories

A pilot programme is necessary for the following reasons:

a) to verify the details in the operation of the test;

b) to find out how well operators can follow the instructions of the method;

c) to check the precautions regarding samples;

d) to estimate approximately the precision of the test.

At least two samples are required, covering the range of results to which the test method is intended to apply;

however, at least twelve laboratory/sample combinations shall be included. Each sample is tested twice by

each laboratory under repeatability conditions. If any omissions or inaccuracies in the draft test method are

revealed, they shall now be corrected. The results shall be analysed for bias and precision; if either is

considered to be too large, then alterations to the test method shall be considered.

4.4 Planning the inter-laboratory programme

There shall be at least five participating laboratories, but it is preferable that there are more in order to reduce

the number of samples required.

The number of samples shall be sufficient to cover the range of the property measured at approximately

equidistant intervals and to give reliability to the precision estimates. If precision is found to vary with the level

of results in the pilot programme, then at least five samples shall be used in the inter-laboratory programme. In

any case, it is necessary to obtain at least 30 degrees of freedom in both repeatability and reproducibility. For

repeatability, this means obtaining a total of at least 30 pairs of results in the programme.

For reproducibility, Table A.1 gives the minimum number of samples required in terms of L, P and Q, where L

is the number of participating laboratories, and P and Q are the ratios of variance component estimates

obtained from the pilot programme. Specifically, P is the ratio of the interaction component to the repeats

component and Q is the ratio of the laboratories component to the repeats component. Annex B gives the

derivation of the equation used. If Q is much larger than P, then 30 degrees of freedom cannot be achieved;

the blank entries in Table A.1 correspond to, or an approach to, this situation (i.e. when more than 20 samples

are required). For these cases, there is likely to be a significant bias between laboratories.

4.5 Executing the inter-laboratory programme

One person shall be responsible for the entire programme, from the distribution of the texts of the test method

and samples to the final appraisal of the results. He shall be familiar with the test method, but shall not

personally take part in the tests.

The text of the test method shall be distributed to all the laboratories in time to allow any queries to be raised

before the tests begin. If any laboratory wants to practice the method in advance, this shall be carried out with

samples other than those used in the programme.

The samples shall be accumulated, subdivided and distributed by the organizer, who shall also keep a reserve

of each sample for emergencies. It is most important that the individual laboratory portions be homogeneous.

They shall be blind coded before distribution and the following information shall be sent with them:

a) agreed (draft) method of test;

b) handling and storage requirements for the samples;

c) order in which the samples are to be tested (a different random order for each laboratory);

d) statement that two results shall be obtained consecutively on each sample by the same operator with the

same apparatus. For statistical reasons, it is imperative that the two results are obtained independently of

each other, that is, that the second result is not biased by knowledge of the first. If this is regarded as

impossible to achieve with the operator concerned, then the pairs of results shall be obtained in a blind

fashion, but ensuring that they are carried out in a short period of time;

e) period of time during which repeated results are to be obtained and the period of time during which all the

samples are to be tested;

f) blank form for reporting the results. For each sample, there shall be space for the date of testing, the two

results, and any unusual occurrences. The unit of accuracy for reporting the results shall be specified;

g) statement that the test shall be carried out under normal conditions, using operators with good experience

but not exceptional knowledge and that the duration of the test shall be the same as normal.

The pilot-programme operators may take part in the inter-laboratory programme. If their extra experience in

testing a few more samples produces a noticeable effect, it serves as a warning that the test method is not

satisfactory. They shall be identified in the report of the results so that any effect can be noted.

5 Inspection of inter-laboratory results for uniformity and for outliers

5.1 General

In 5.2 to 5.7, procedures are specified for examining the results reported in a statistically designed inter-

laboratory programme (see Clause 4) in order to establish the following:

a) independence or dependence of precision and the level of results;

b) uniformity of precision from laboratory to laboratory;

c) and to detect the presence of outliers.

The procedures are described in mathematical terms based on the notation of Annex C and illustrated with

reference to the example data (calculation of bromine number) set out in Annex D.

Throughout 5.2 to 5.7 (and Clause 6), the procedures used are first specified and then illustrated by a worked

example using data given in Annex D.

It is assumed throughout this clause that all the results are either from a single normal distribution or capable

of being transformed into such a distribution (see 5.2). Other cases (which are rare) require a different

treatment that is beyond the scope of this International Standard. See Reference [8] for a statistical test on

normality.

Although the procedures shown here are in a form suitable for hand calculation, it is strongly advised that an

electronic computer with appropriately validated software be used to store and analyse inter-laboratory test

results, based on the procedures of this International Standard (see, for example, Reference [9]).

6 © ISO 2006 – All rights reserved

5.2 Transformation of data

5.2.1 General

In many test methods, the precision depends on the level of the test result, and thus the variability of the

reported results is different from sample to sample. The method of analysis outlined in this International

Standard requires that this shall not be so and the position is rectified, if necessary, by a transformation.

The laboratories standard deviations, D , and the repeats standard deviations, d , for sample j (see Annex C)

j j

are calculated and plotted separately against the sample means, m . If the points so plotted can be considered

j

as lying about a pair of lines parallel to the m-axis, then no transformation is necessary. If, however, the

plotted points describe non-horizontal straight lines or curves of the form D = f (m) and d = f (m), then a

1 2

transformation is necessary.

The relationships D = f (m) and d = f (m) are not, in general, identical. The statistical procedures of this

1 2

International Standard require, however, that the same transformation be applicable both for repeatability and

for reproducibility. For this reason, the two relationships are combined into a single dependency relationship

D = f(m) (where D now includes d) by including a dummy variable, T. This takes account of the difference

between the relationships, if one exists, and provides a means of testing for this difference (see Clause F.1).

The single relationship D = f(m) is best estimated by a weighted linear regression analysis, even though in

most cases an unweighted regression gives a satisfactory approximation. The derivation of weights is

described in Clause F.2, and the computational procedure for the regression analysis is described in

Clause F.3. Typical forms of dependence D = f(m) are given in Clause E.1. These are all expressed in terms of

transformation parameters B and B .

The estimation of B and B , and the transformation procedure which follows, are summarized in Clause E.2.

This includes statistical tests for the significance of the regression (i.e. is the relationship D = f(m) parallel to

the m-axis), and for the difference between the repeatability and reproducibility relationships, based at the 5 %

significance level. If such a difference is found to exist, or if no suitable transformation exists, then the

alternative sample-by-sample procedures of ISO 5725-2 shall be used. In such an event, it is not possible to

test for laboratory bias over all samples (see 5.6) or separately estimate the interaction component of variance

(see 6.2).

If it has been shown at the 5 % significance level that there is a significant regression of the form D = f(m),

then the appropriate transformation y = F(x), where x is the reported result, is given by the equation:

dx

Fx =K (2)

()

∫

f x

()

where K is a constant. In that event, all results shall be transformed accordingly and the remainder of the

analysis carried out in terms of the transformed results. Typical transformations are given in Clause E.1.

It is difficult to make the choice of transformation the subject of formalized rules. Qualified statistical

assistance can be required in particular cases. The presence of outliers can affect judgement as to the type of

transformation required, if any (see 5.7).

5.2.2 Worked example

Table 1 lists the values of m, D, and d for the eight samples in the example given in Annex D, correct to three

significant digits. Corresponding degrees of freedom are in parentheses.

Table 1

Sample

3 8 1 4 5 6 2 7

number

m 0,756 1,22 2,15 3,64 10,9 48,2 65,4 114

D 0,066 9 (14) 0,159 (9) 0,729 (8) 0,211 (11) 0,291 (9) 1,50 (9) 2,22 (9) 2,93 (9)

d 0,050 0 (9) 0,057 2 (9) 0,127 (9) 0,116 (9) 0,094 3 (9) 0,527 (9) 0,818 (9) 0,935 (9)

Inspection of the figures in Table 1 shows that both D and d increase with m, the rate of increase diminishing

as m increases. A plot of these figures on log-log paper (i.e. a graph of log D and log d against log m) shows

that the points may reasonably be considered as lying about two straight lines (see Figure F.1) From the

example calculations given in Clause F.4, the gradients of these lines are shown to be the same, with an

estimated value of 0,638. Bearing in mind the errors in this estimated value, the gradient may, for convenience,

be taken as 2/3.

Hence, the same transformation is appropriate both for repeatability and reproducibility, and is given by the

equation:

−23 13

xxd3=x (3)

∫

Since the constant multiplier may be ignored, the transformation thus reduces to that of taking the cube roots

of the reported results (bromine numbers). This yields the transformed data shown in Table D.2, in which the

cube roots are quoted correct to three decimal places.

5.3 Tests for outliers

5.3.1 General

The reported data, or if it has been decided that a transformation is necessary, the transformed results, shall

be inspected for outliers. These are the values that are so different from the remaining data that it can only be

concluded that they have arisen from some fault in the application of the test method or from testing a wrong

sample. Many possible tests may be used and the associated significance levels varied, but those that are

given below have been found to be appropriate for this International Standard. These outlier tests all assume

a normal distribution of errors (see 5.1).

5.3.2 Uniformity of repeatability

5.3.2.1 General

[1]

The first outlier test is concerned with detecting a discordant result in a pair of repeat results. This test

involves calculating the e over all the laboratory/sample combinations. Cochran's criterion at the 1 %

ij

significance level is then used to test the ratio of the largest of these e values over their sum (see

ij

Clause C.5). If its value exceeds the value given in Table D.3, corresponding to one degree of freedom, n

being the number of pairs available for comparison, then the member of the pair farthest from the sample

mean shall be rejected and the process repeated, reducing n by 1, until no more rejections are called for. In

certain cases, this test “snowballs” and leads to an unacceptably large proportion of rejections (say more than

10 %). If this is so, this rejection test shall be abandoned and some or all of the rejected results shall be

retained. An arbitrary decision based on judgement is necessary in this case.

5.3.2.2 Worked example

In the case of the example given in Annex D, the absolute differences (ranges) between transformed repeat

results, i.e. of the pairs of numbers in Table D.2, in units of the third decimal place, are shown in Table 2.

8 © ISO 2006 – All rights reserved

Table 2

Sample

Laboratory

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

A 42 21 7 13 7 10 8 0

B 23 12 12 0 7 9 3 0

C 0 6 0 0 7 8 4 0

D 14 6 0 13 0 8 9 32

E 65 4 0 0 14 5 7 28

F 23 20 34 29 20 30 43 0

G 62 4 78 0 0 16 18 56

H 44 20 29 44 0 27 4 32

J 0 59 0 40 0 30 26 0

The largest range is 0,078 for laboratory G on sample 3. The sum of squares of all the ranges is

22 22

0,042++0,021 …+ 0,026+ 0= 0,043 9

0,078

Thus, the ratio to be compared with Cochran's criterion is = 0,138

0,043 9

There are 72 ranges and, as from Table D.3, the criterion for 80 ranges is 0,170 9, this ratio is not significant.

5.3.3 Uniformity of reproducibility

5.3.3.1 General

The following outlier tests are concerned with establishing uniformity in the reproducibility estimate and are

designed to detect either a discordant pair of results from a laboratory on a particular sample or a discordant

[2]

set of results from a laboratory on all samples. For both purposes, the Hawkins' test is appropriate.

This involves forming for each sample, and finally for the overall laboratory averages (see 5.6), the ratio of the

largest absolute deviation of laboratory mean from sample (or overall) mean to the square root of certain sums

of squares (see Clause C.6).

The ratio corresponding to the largest absolute deviation shall be compared with the critical 1 % values given

in Table D.4, where n is the number of laboratory/sample cells in the sample (or the number of overall

laboratory means) concerned and where ν is the degrees of freedom for the sum of squares, which is

additional to that corresponding to the sample in question. In the test for laboratory/sample cells, ν refers to

other samples, but is zero in the test for overall laboratory averages.

If a significant value is encountered for individual samples, the corresponding extreme values shall be omitted

and the process repeated. If any extreme values are found in the laboratory totals, then all the results from

that laboratory shall be rejected.

If the test “snowballs”, leading to an unacceptably large proportion of rejections (say more than 10 %), then

this rejection test shall be abandoned and some or all of the rejected results shall be retained. An arbitrary

decision based on judgement is necessary in this case.

5.3.3.2 Worked example

The application of Hawkins' test to cell means within samples is shown below.

The first step is to calculate the deviations of cell means from respective sample means over the whole array.

These are shown in Table 3, in units of the third decimal place.

The sum of squares of the deviations are then calculated for each sample. These are also shown in Table 3 in

units of the third decimal place.

Table 3

Sample

Laboratory

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

A 20 8 14 15 10 48 6 3

B 75 7 20 9 10 47 6 3

C 64 35 3 20 30 4 22 25

D 314 33 18 42 7 39 80 50

E 32 32 30 9 7 18 18 39

F 75 97 31 20 30 8 74 53

G 10 34 32 20 20 61 9 62

H 42 13 4 42 13 21 8 50

J 1 28 22 29 14 8 10 53

Sum of squares 117 15 4 6 3 11 13 17

The cell tested is the one with the most extreme deviation. This was obtained by laboratory D from sample 1.

The appropriate Hawkins' test ratio is therefore

0,314

B*0==,7281

0,117++0,015 .+ 0,017

The critical value, corresponding to n = 9 cells in sample 1 and ν = 56 extra degrees of freedom from the other

samples, is interpolated from Table D.4 as 0,372 9. The test value is greater than the critical value and so the

results from laboratory D on sample 1 are rejected.

As there has been a rejection, the mean value, deviations and sum of squares are recalculated for sample 1,

and the procedure is repeated. The next cell to be tested is that obtained by laboratory F from sample 2. The

Hawkins' test ratio for this cell is:

0,097

B*0==,3542

0,006++0,015 .+ 0,017

The critical value corresponding to n = 9 cells in sample 2 and ν = 55 extra degrees of freedom is interpolated

from Table D.4 as 0,375 6. As the test ratio is less than the critical value, there are no further rejections.

10 © ISO 2006 – All rights reserved

5.4 Rejection of complete data from a sample

5.4.1 General

The laboratories standard deviation and repeats standard deviation shall be examined for any outlying

samples. If a transformation has been carried out or any rejection made, new standard deviations shall be

calculated.

If the standard deviation for any sample is excessively large, it shall be examined with a view to rejecting the

results from that sample.

Cochran's criterion at the 1 % level can be used when the standard deviations are based on the same number

of degrees of freedom. This involves calculating the ratio of the largest of the corresponding sums of squares

(laboratories or repeats, as appropriate) to their total (see Clause C.5). If the ratio exceeds the critical value

given in Table D.3, with n as the number of samples and ν the degrees of freedom, then all the results from

the sample in question shall be rejected. In such an event, care should be taken that the extreme standard

deviation is not due to the application of an inappropriate transformation (see 5.2), or undetected outliers.

There is no optimal test when standard deviations are based on different degrees of freedom. However, the

ratio of the largest variance to that pooled from the remaining samples follows an F-distribution with ν and ν

1 2

degrees of freedom (see Clause C.7). Here ν is the degrees of freedom of the variance in question and ν is

1 2

the degrees of freedom for the remaining samples. If the ratio is greater than the critical value given in

Tables D.6 to D.10, corresponding to a significance level of 0,01/S, where S is the number of samples, then

results from the sample in question shall be rejected.

5.4.2 Worked example

The standard deviations of the transformed results, after the rejection of the pair of results by laboratory D on

sample 1, are given in Table 4 in ascending order of sample mean, correct to three significant digits.

Corresponding degrees of freedom are in parentheses.

Inspection shows that there is no outlying sample amongst these. It is noted that the standard deviations are

now independent of the sample means, which was the purpose of transforming the results.

The figures in Table 5, taken from a test programme on bromine numbers over 100, illustrate the case of a

sample rejection.

It is clear, by inspection, that the laboratories' standard deviation for sample 93 at 15,26 is far greater than the

others. It is noted that the repeats standard deviation in this sample is correspondingly large.

Table 4

Sample number 3 8 1 4 5 6 2 7

Sample mean 0,910 0 1,066 1,240 1,538 2,217 3,639 4,028 4,851

Laboratories standard

0,027 8 (14) 0,047 3 (9) 0,035 4 (13) 0,029 7 (11) 0,019 7 (9) 0,037 8 (9) 0,045 0 (9) 0,041 6 (9)

deviation

Repeats standard

0,021 4 (9) 0,018 2 (9) 0,028 1 (8) 0,016 4 (9) 0,006 3 (9) 0,013 2 (9) 0,016 6 (9) 0,013 0 (9)

deviation

Table 5

Sample number 90 89 93 92 91 94 95 96

Sample mean 96,1 99,8 119,3 125,4 126,0 139,1 139,4 159,5

Laboratories standard deviation 5,10 (8) 4,20 (9) 15,26 (8) 4,40 (11) 4,09 (10) 4,87 (8) 4,74 (9) 3,85 (8)

Repeats standard deviation

1,13 (8) 0,99 (8) 2,97 (8) 0,91 (8) 0,73 (8) 1,32 (8) 1,12 (8) 1,36 (8)

Since laboratory degrees of freedom are not the same over all samples, the variance ratio test is used. The

variance pooled from all samples excluding sample 93 is the sum of the sums of squares divided by the total

degrees of freedom, that is:

22 2

⎡⎤

8×+5,10 9× 4,20+ .+ 8× 3,85

()( ) ( )

⎢⎥

⎣⎦

= 19,96

(8++9 .+ 8)

The variance ratio is then calculated as (15,26 )/19,96 = 11,66.

From Tables D.6 to D.10, the critical value corresponding to a significance level of 0,01/8 = 0,001 25, for 8 and

63 degrees of freedom, is approximately 4. This is less than the test ratio and results from sample 93 shall.

therefore, be rejected.

Turning to repeats standard deviations, it is noted that degrees of freedom are identical for each sample and

that Cochran's test can therefore be applied. Cochran's criterion is the ratio of the largest sum of squares

(sample 93) to the sum of all the sums of squares, that is:

2 2 2 2

2,97 /(1,13 + 0,99 + . + 1,36 ) = 0,510

This is greater than the critical value of 0,352 corresponding to n = 8 and ν = 8 (see Table D.3), and confirms

that results from sample 93 shall be rejected.

5.5 Estimating missing or rejected values

5.5.1 One of the two repeat values missing or rejected

If one of a pair of repeats (y or y ) is missing or rejected, this shall be considered to have the same value as

ij1 ij2

the other repeat in accordance with the least squares method.

5.5.2 Both repeat values missing or rejected

5.5.2.1 General

If both the repeat values are missing, estimates of a (= y + y ) shall be made by forming the

ij ij1 ij2

laboratories × samples interaction sum of squares, including the missing values of the totals of the

laboratories/samples pairs of results as

...

NORME ISO

INTERNATIONALE 4259

Troisième édition

2006-08-01

Produits pétroliers — Détermination

et application des valeurs de fidélité

relatives aux méthodes d'essai

Petroleum products — Determination and application of precision data

in relation to methods of test

Numéro de référence

©

ISO 2006

PDF – Exonération de responsabilité

Le présent fichier PDF peut contenir des polices de caractères intégrées. Conformément aux conditions de licence d'Adobe, ce fichier

peut être imprimé ou visualisé, mais ne doit pas être modifié à moins que l'ordinateur employé à cet effet ne bénéficie d'une licence

autorisant l'utilisation de ces polices et que celles-ci y soient installées. Lors du téléchargement de ce fichier, les parties concernées

acceptent de fait la responsabilité de ne pas enfreindre les conditions de licence d'Adobe. Le Secrétariat central de l'ISO décline toute

responsabilité en la matière.

Adobe est une marque déposée d'Adobe Systems Incorporated.

Les détails relatifs aux produits logiciels utilisés pour la création du présent fichier PDF sont disponibles dans la rubrique General Info

du fichier; les paramètres de création PDF ont été optimisés pour l'impression. Toutes les mesures ont été prises pour garantir

l'exploitation de ce fichier par les comités membres de l'ISO. Dans le cas peu probable où surviendrait un problème d'utilisation,

veuillez en informer le Secrétariat central à l'adresse donnée ci-dessous.

© ISO 2006

Droits de reproduction réservés. Sauf prescription différente, aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite ni utilisée sous

quelque forme que ce soit et par aucun procédé, électronique ou mécanique, y compris la photocopie et les microfilms, sans l'accord écrit

de l'ISO à l'adresse ci-après ou du comité membre de l'ISO dans le pays du demandeur.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax. + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Publié en Suisse

ii © ISO 2006 – Tous droits réservés

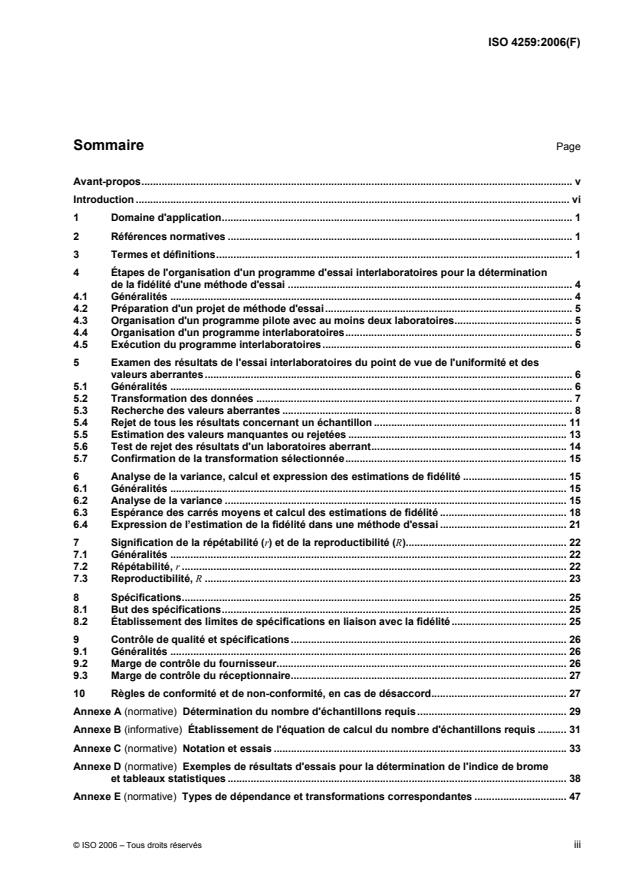

Sommaire Page

Avant-propos. v

Introduction . vi

1 Domaine d'application. 1

2 Références normatives . 1

3 Termes et définitions. 1

4 Étapes de l'organisation d'un programme d'essai interlaboratoires pour la détermination

de la fidélité d'une méthode d'essai . 4

4.1 Généralités . 4

4.2 Préparation d'un projet de méthode d'essai.5

4.3 Organisation d'un programme pilote avec au moins deux laboratoires. 5

4.4 Organisation d'un programme interlaboratoires. 5

4.5 Exécution du programme interlaboratoires. 6

5 Examen des résultats de l'essai interlaboratoires du point de vue de l'uniformité et des

valeurs aberrantes. 6

5.1 Généralités . 6

5.2 Transformation des données . 7

5.3 Recherche des valeurs aberrantes . 8

5.4 Rejet de tous les résultats concernant un échantillon . 11

5.5 Estimation des valeurs manquantes ou rejetées . 13

5.6 Test de rejet des résultats d'un laboratoires aberrant. 14

5.7 Confirmation de la transformation sélectionnée. 15

6 Analyse de la variance, calcul et expression des estimations de fidélité . 15

6.1 Généralités . 15

6.2 Analyse de la variance . 15

6.3 Espérance des carrés moyens et calcul des estimations de fidélité . 18

6.4 Expression de l’estimation de la fidélité dans une méthode d'essai . 21

7 Signification de la répétabilité (r) et de la reproductibilité (R). 22

7.1 Généralités . 22

7.2 Répétabilité, r . 22

7.3 Reproductibilité, R . 23

8 Spécifications. 25

8.1 But des spécifications. 25

8.2 Établissement des limites de spécifications en liaison avec la fidélité. 25

9 Contrôle de qualité et spécifications. 26

9.1 Généralités . 26

9.2 Marge de contrôle du fournisseur. 26

9.3 Marge de contrôle du réceptionnaire. 27

10 Règles de conformité et de non-conformité, en cas de désaccord. 27

Annexe A (normative) Détermination du nombre d'échantillons requis. 29

Annexe B (informative) Établissement de l'équation de calcul du nombre d'échantillons requis . 31

Annexe C (normative) Notation et essais . 33

Annexe D (normative) Exemples de résultats d'essais pour la détermination de l'indice de brome

et tableaux statistiques . 38

Annexe E (normative) Types de dépendance et transformations correspondantes . 47

Annexe F (normative) Analyse de régression linéaire pondérée . 51

Annexe G (normative) Règles d'arrondissage des résultats . 58

Annexe H (informative) Explication des équations données dans l'Article 7 . 59

Annexe I (informative) Spécifications relatives à un degré spécifié de caractère critique. 61

Bibliographie . 64

iv © ISO 2006 – Tous droits réservés

Avant-propos

L'ISO (Organisation internationale de normalisation) est une fédération mondiale d'organismes nationaux de

normalisation (comités membres de l'ISO). L'élaboration des Normes internationales est en général confiée

aux comités techniques de l'ISO. Chaque comité membre intéressé par une étude a le droit de faire partie du

comité technique créé à cet effet. Les organisations internationales, gouvernementales et non

gouvernementales, en liaison avec l'ISO participent également aux travaux. L'ISO collabore étroitement avec

la Commission électrotechnique internationale (CEI) en ce qui concerne la normalisation électrotechnique.

Les Normes internationales sont rédigées conformément aux règles données dans les Directives ISO/CEI,

Partie 2.

La tâche principale des comités techniques est d'élaborer les Normes internationales. Les projets de Normes

internationales adoptés par les comités techniques sont soumis aux comités membres pour vote. Leur

publication comme Normes internationales requiert l'approbation de 75 % au moins des comités membres

votants.

L'attention est appelée sur le fait que certains des éléments du présent document peuvent faire l'objet de

droits de propriété intellectuelle ou de droits analogues. L'ISO ne saurait être tenue pour responsable de ne

pas avoir identifié de tels droits de propriété et averti de leur existence.

L'ISO 4259 a été élaborée par le comité technique ISO/TC 28, Produits pétroliers et lubrifiants.

Cette troisième édition annule et remplace la deuxième édition (ISO 4259:1992), dont les Articles 1, 5, 7, C.7,

E.2 et F.3 et les paragraphes 4.2, 5.2, 6.3.2, 6.3.3.1, 6.3.3.3, 6.4, 8.2, 10.2, 10.4 et 10.5 ont fait l'objet d'une

révision technique. Elle incorpore également le Rectificatif technique ISO 4259:1992/Cor.1:1993.

Introduction

Pour les besoins de contrôle de qualité et pour vérifier leur conformité aux spécifications, les caractéristiques

des produits pétroliers commerciaux sont contrôlées au moyen de méthodes d'essai normalisées de

laboratoires. Deux ou plusieurs déterminations de la même caractéristique d'un échantillon donné, selon une

méthode d'essai donnée, ne donnent généralement pas exactement le même résultat. Il est donc nécessaire

de tenir compte correctement de ce fait, en parvenant à des estimations fondées sur les statistiques de la

fidélité d'une méthode, qui constituent une mesure objective du degré de concordance attendu entre deux ou

plusieurs résultats obtenus dans des conditions données.

[11]

L’ISO 4259 fait référence à l’ISO 3534-2 , qui donne une définition différente de la valeur vraie (voir 3.26).

L’ISO 4259 fait aussi référence à l’ISO 5725-2, qui est nécessaire pour l’estimation de la fidélité dans des

circonstances particulières et inhabituelles (voir 5.2).

vi © ISO 2006 – Tous droits réservés

NORME INTERNATIONALE ISO 4259:2006(F)

Produits pétroliers — Détermination et application des valeurs

de fidélité relatives aux méthodes d'essai

1 Domaine d'application

La présente Norme internationale traite du calcul des estimations de fidélité et de leur application aux

spécifications. En particulier, elle contient les définitions des termes statistiques concernés (Article 3), les

procédures à suivre dans l'organisation d'un programme d'essai interlaboratoires destiné à déterminer la

fidélité d'une méthode d'essai (Article 4), la méthode de calcul de la fidélité à partir des résultats d'un tel

programme (Article 5 et Article 6) et la procédure à suivre dans l'interprétation des résultats de laboratoires, à

la lumière de la fidélité des méthodes de test et des limites fixées dans les spécifications (Articles 7 à 10).

Les procédures de la présente Norme internationale ont été conçues spécifiquement pour les produits

pétroliers et leurs produits connexes, qui sont normalement homogènes. Cependant, on reconnaît que les

procédures décrites dans la présente Norme internationale peuvent aussi s’appliquer à d’autres types de

produits homogènes. Des contrôles attentifs s’avèrent nécessaires avant d’appliquer la présente Norme

internationale à des produits pour lesquels la présomption d’homogénéité peut être mise en question.

2 Références normatives

Les documents de référence suivants sont indispensables pour l'application du présent document. Pour les

références datées, seule l'édition citée s'applique. Pour les références non datées, la dernière édition du

document de référence s'applique (y compris les éventuels amendements).

ISO 5725-2:1994, Exactitude (justesse et fidélité) des résultats et méthodes de mesure — Partie 2: Méthode

de base pour la détermination de la répétabilité et de la reproductibilité d'une méthode de mesure normalisée

3 Termes et définitions

Pour les besoins du présent document, les termes et définitions suivants s'appliquent.

3.1

analyse de variance

technique qui permet de décomposer la variance totale d'une méthode en ses différents facteurs composants

3.2

variance interlaboratoires

élément de la variance totale dû aux différences entre les valeurs moyennes des différents laboratoires

NOTE 1 Lorsque des résultats obtenus par plus d'un laboratoires sont comparés, la dispersion est normalement plus

importante que lorsque le même nombre d'essais est effectué par un seul laboratoires, et il y a des écarts entre les

moyennes obtenues par les différents laboratoires. Ces écarts donnent lieu à la variance interlaboratoires.

NOTE 2 Il existe une définition correspondante pour la variance entre opérateurs.

NOTE 3 Le terme «interlaboratoires» est souvent abrégé en «laboratoires» lorsqu'il est utilisé pour qualifier des

paramètres représentatifs de la dispersion de la population de résultats, par exemple sous forme de «variance de

laboratoires».

3.3

biais

différence entre la valeur vraie (associée à la méthode d'essai) et la valeur connue, lorsque celle-ci est

disponible

NOTE Pour une définition de la valeur vraie et de la valeur connue, voir 3.26 et 3.8, respectivement.

3.4

codage aveugle

attribution d'un numéro différent pour chaque échantillon, afin qu'aucune autre identification ou information sur

les échantillons ne soit donnée à l'opérateur

3.5

échantillon de contrôle

échantillon prélevé au lieu où le produit est échangé, c'est-à-dire où la responsabilité de la qualité du produit

passe du fournisseur au réceptionnaire

3.6

degrés de liberté

diviseur utilisé dans le calcul de la variance; une unité de moins que le nombre de résultats indépendants

NOTE La définition n'est strictement applicable que dans les cas les plus simples. Des définitions plus complètes

sont en dehors de l'objet de la présente Norme internationale.

3.7

détermination

exécution de la série d'opérations spécifiées dans la méthode d'essai et permettant d'obtenir une seule valeur

3.8

valeur connue

valeur quantitative réelle découlant de la préparation de l'échantillon

NOTE La valeur connue n'existe pas toujours, par exemple dans le cas d'essais empiriques tels que la détermination

du point d'éclair.

3.9

moyenne

moyenne arithmétique

pour une série donnée de résultats, somme des résultats divisée par leur nombre

3.10

moyenne des carrés

somme des carrés divisée par le nombre de degrés de liberté

3.11

distribution normale

distribution de probabilité d'une variable aléatoire continue x, telle que si x est un nombre réel quelconque, la

densité de probabilité est:

⎡⎤

11⎛⎞x − µ

fx()=−exp⎢⎥,−∞

⎜⎟

2 σ

σ 2π⎢⎥

⎝⎠

⎣⎦

NOTE µ est la valeur vraie et σ est l'écart-type de la distribution normale (σ > 0).

3.12

opérateur

personne qui effectue normalement et régulièrement un essai particulier

2 © ISO 2006 – Tous droits réservés

3.13

valeur aberrante

résultat dont la valeur est suffisamment éloignée des autres résultats pour qu'il ne soit pas considéré comme

faisant partie de l'ensemble des résultats

3.14

fidélité

étroitesse de l'accord entre les résultats obtenus en appliquant le procédé expérimental à plusieurs reprises

sur des produits identiques et dans des conditions déterminées

NOTE Le procédé est d'autant plus fidèle que la partie aléatoire des erreurs expérimentales qui affectent les résultats

est moindre.

3.15

erreur aléatoire

possibilité d'erreur dans tout essai en dépit du meilleur contrôle possible des variables

3.16

réceptionnaire

toute personne physique ou morale qui reçoit ou accepte le produit livré par le fournisseur

3.17

répétabilité

〈qualitativement〉 étroitesse de l'accord entre des résultats indépendants obtenus dans l'exécution normale et

correcte de la même méthode sur un produit identique soumis à l'essai, dans les mêmes conditions (même

opérateur, même appareillage, même laboratoires et courts intervalles de temps)

NOTE Les paramètres représentatifs de la dispersion de la population qui peut être associée au résultat sont

qualifiés du terme répétabilité, par exemple écart-type de répétabilité ou variance de répétabilité. Il convient de ne pas

confondre le terme «répétabilité» avec le terme «entre répétitions» ou «répétitions» lorsqu'il est utilisé de cette manière

(voir 3.19). La répétabilité se réfère à l'état de variabilité aléatoire minimale des résultats. Le temps pendant lequel des

résultats répétés doivent être obtenus sera donc suffisamment court pour exclure les erreurs qui dépendent du temps, par

exemple les erreurs dues à l'ambiance et à l'étalonnage.

3.18

répétabilité

〈quantitativement〉 valeur égale ou au dessous de laquelle la différence absolue entre deux résultats

individuels obtenus dans les conditions spécifiées est attendue, pour une probabilité de 95 %

NOTE Pour des détails sur les conditions spécifiées, voir 3.17.

3.19

répétition

exécution d'une méthode d'essai plus d'une fois pour améliorer la fidélité et obtenir une meilleure estimation

de l'erreur de détermination

NOTE Il convient de distinguer une répétition d'une redétermination dans la mesure où le premier terme implique que

les essais sont effectués à un seul endroit et, autant que possible, sur une seule période de temps. Les paramètres

représentatifs de la dispersion de la population qui peuvent être associés avec des expériences répétées sont qualifiés du

terme «entre répétitions» ou, sous une forme abrégée, de «répétitions», par exemple «écart-type des répétitions».

3.20

reproductibilité

〈qualitativement〉 étroitesse de l'accord entre des résultats individuels obtenus dans l'exécution normale et

correcte de la même méthode sur un produit identique soumis à l'essai, mais dans des conditions différentes

(opérateurs différents, appareillages différents et laboratoires différents)

NOTE Les paramètres représentatifs de la dispersion de la population qui peuvent être associés aux résultats sont

qualifiés du terme «reproductibilité», par exemple écart-type de reproductibilité ou variance de reproductibilité

3.21

reproductibilité

〈quantitativement〉 valeur à laquelle la différence absolue entre deux résultats individuels sur un produit

identique obtenus par des opérateurs différents dans des laboratoires différents, en utilisant la méthode

d'essai normalisée, doit rester égale ou inférieure, pour une probabilité spécifiée de 95 %

3.22

résultat

valeur finale obtenue en suivant le mode opératoire complet de la méthode d'essai, cette valeur pouvant être

obtenue au moyen d'une seule ou de plusieurs déterminations suivant les instructions de la méthode

NOTE Il est admis que le résultat est arrondi conformément à la procédure spécifiée dans l'Annexe G.

3.23

écart-type

mesure de la dispersion d'une série de résultats autour de leur moyenne, égale à la racine carrée positive de

la variance et estimée par la racine carrée positive de la moyenne des carrés

3.24

somme des carrés

somme des carrés de la différence entre une série de résultats et leur moyenne

3.25

fournisseur

toute personne physique ou morale responsable de la qualité d'un produit juste avant qu'il ne soit pris en

charge par le réceptionnaire

3.26

valeur vraie

pour les besoins pratiques, valeur vers laquelle tend la moyenne des résultats individuels obtenus par n

laboratoires, lorsque n tend vers l'infini

NOTE 1 Une valeur vraie ainsi définie est associée à chaque méthode d'essai particulière.

[11]

NOTE 2 Une définition différente et idéalisée est donnée dans l'ISO 3534-2 .

3.27

variance

moyenne des carrés de l'écart d'une variable aléatoire par rapport à sa moyenne, estimée par la moyenne

des carrés

4 Étapes de l'organisation d'un programme d'essai interlaboratoires pour la

détermination de la fidélité d'une méthode d'essai

4.1 Généralités

Les étapes de l'organisation d'un programme d'essai interlaboratoires sont les suivantes:

a) préparation d'un projet de méthode d'essai;

b) organisation d'un programme pilote avec au moins deux laboratoires;

c) organisation du programme interlaboratoires;

d) exécution du programme interlaboratoires.

Les quatre étapes sont décrites successivement de 4.2 à 4.5.

4 © ISO 2006 – Tous droits réservés

4.2 Préparation d'un projet de méthode d'essai

Celui-ci doit contenir tous les détails nécessaires pour l'exécution de l'essai et l'expression des résultats.

Toute condition susceptible d'avoir une influence sur les résultats doit être spécifiée.

À ce stade, seul le titre de l'article relatif à la fidélité est inclus dans le projet de méthode d’essai. Il est

recommandé que la limite inférieure du domaine d'application de la méthode d'essai ne soit pas inférieure à la

plus petite valeur testée dans le programme interlaboratoires et soit au moins plus grand de 2R au plus petit

résultat qui puisse être déterminé (voir 8.2), R étant l’estimation de la reproductibilité. De la même manière, il

est recommandé que la limite supérieure du domaine d'application de la méthode d'essai n'excède pas la

valeur maximale testée au cours du programme interlaboratoires et soit au moins supérieure de 2R au résultat

le plus élevé que l’on puisse atteindre.

4.3 Organisation d'un programme pilote avec au moins deux laboratoires

Un programme pilote est nécessaire pour les raisons suivantes:

a) pour vérifier les détails de l'exécution de l'essai;

b) pour déterminer dans quelle mesure les opérateurs peuvent observer correctement les instructions de la

méthode;

c) pour contrôler les instructions concernant les échantillons;

d) pour estimer grossièrement la fidélité de l'essai.

Au moins deux échantillons sont nécessaires, couvrant la plage de résultats pour laquelle la méthode d'essai

est conçue. Cependant, au moins douze combinaisons laboratoires/échantillon doivent être incluses. Chaque

échantillon est essayé deux fois par chaque laboratoires dans les conditions de répétabilité. Si des omissions

ou des imprécisions dans le projet de méthode d’essai sont révélées, elles doivent alors être corrigées. Les

résultats doivent être analysés sous l'angle du biais et de la fidélité: si l'un ou l'autre paraît trop important, des

modifications à la méthode d’essai doivent être envisagées.

4.4 Organisation d'un programme interlaboratoires

Celui-ci doit recueillir la participation d'au moins cinq laboratoires, mais il est préférable de dépasser ce

nombre pour réduire le nombre d'échantillons requis.

Le nombre d'échantillons doit être suffisant pour couvrir la plage de la propriété mesurée et rendre sûres les

estimations de fidélité. Si une quelconque variation de la fidélité avec le niveau des résultats est observée

dans le programme pilote, il devient nécessaire d'utiliser au moins cinq échantillons dans le programme

interlaboratoires. Dans tous les cas, il est nécessaire d'obtenir au moins 30 degrés de liberté pour la

répétabilité et la reproductibilité. Pour la répétabilité, cela signifie un total de 30 paires de résultats dans le

programme.

Pour la reproductibilité, le Tableau A.1 donne le nombre minimal d'échantillons requis en fonction de L, P et Q,

où L est le nombre de laboratoires participants et P et Q sont les rapports des estimations des composantes

de variance obtenues dans le programme pilote. Spécifiquement, P est le rapport de la composante

interaction à la composante répétitions et Q est le rapport de la composante laboratoires à la composante

répétitions. L'Annexe B donne le calcul de la formule utilisée. Si Q est beaucoup plus grand que P, les

30 degrés de liberté ne peuvent être atteints; les entrées vides dans le Tableau A.1 correspondent à cette

situation ou à une situation proche (c'est-à-dire lorsque plus de 20 échantillons sont nécessaires). Dans ces

cas, il y a vraisemblablement un biais significatif entre laboratoires.

4.5 Exécution du programme interlaboratoires

Une personne doit être responsable du programme entier, depuis la distribution des textes de la méthode

d’essai et des échantillons jusqu'à l'évaluation finale des résultats. Elle doit bien connaître la méthode d’essai,

mais ne doit pas prendre part personnellement aux essais.

Le texte de la méthode d’essai doit être diffusé à tous les laboratoires pour leur permettre de soulever

d'éventuelles questions avant le début des essais. Si un laboratoires désire pratiquer la méthode à l'avance,

cela doit être fait sur des échantillons autres que ceux utilisés dans le programme.

Les échantillons doivent être réunis, divisés et distribués par l'organisateur, qui doit également conserver une

réserve de chaque échantillon pour les cas urgents. Il est de la plus haute importance que les parties

fractionnées pour chaque laboratoires soient homogènes. Celles-ci doivent être codées avant la distribution,

et les informations suivantes doivent accompagner leur envoi.

a) La méthode (ou le projet de méthode) choisie pour les essai.

b) Les instructions pour la manipulation et le stockage des échantillons.

c) L'ordre dans lequel les échantillons doivent être soumis à l'essai (un ordre aléatoire différent pour chaque

laboratoires).

d) L'indication que deux résultats doivent être obtenus consécutivement sur chaque échantillon, par le

même opérateur avec le même appareillage. Pour des raisons statistiques, il est impératif que les deux

résultats soient obtenus indépendamment l'un de l'autre, c'est-à-dire que le second résultat ne soit pas

influencé par la connaissance du premier. Si cela est considéré comme impossible à atteindre par

l'opérateur concerné, les paires de résultats doivent être dans ce cas obtenues à l'aveugle, mais en

s'assurant que les essais sont exécutés sur une période de temps courte.

e) La période durant laquelle des résultats répétés doivent être obtenus et la période durant laquelle tous

les échantillons doivent être soumis à l'essai.

f) Un formulaire en blanc pour le report des résultats. Pour chaque échantillon, il doit être prévu la date de

l'essai, les deux résultats et toute circonstance inhabituelle. Le degré d'exactitude pour l'expression des

résultats doit être spécifié.

g) L'indication que l'essai doit être exécuté dans des conditions normales, par des opérateurs ayant une

bonne expérience mais pas de connaissances particulières; et que la durée de l'essai doit être conforme

à ce qui se fait normalement.

Les opérateurs du programme pilote peuvent prendre part au programme interlaboratoires. Si le surcroît

d'expérience qu'ils ont acquis lors de l'essai de quelques échantillons supplémentaires produit un effet notable,

cela devrait servir d'avertissement sur le fait que la méthode d’essais n'est pas satisfaisante. Ils doivent être

identifiés dans le compte rendu des résultats de sorte que tout effet puisse être noté.

5 Examen des résultats de l'essai interlaboratoires du point de vue de l'uniformité

et des valeurs aberrantes

5.1 Généralités

Les paragraphes 5.2 à 5.7 spécifient les procédures d'examen des résultats exprimés dans un essai circulaire

organisé dans un but statistique (voir l’Article 4) pour:

a) établir l'indépendance ou la dépendance de la fidélité et le niveau des résultats;

b) établir l'uniformité de la fidélité d'un laboratoires à un autre;

c) détecter la présence de valeurs aberrantes.

6 © ISO 2006 – Tous droits réservés

Les procédures sont décrites en termes mathématiques basés sur la notation de l'Annexe C et illustrées par

des références aux données de l'exemple (calcul de l'indice de brome) exposé dans l'Annexe D.

De 5.2 à 5.7 (et dans l'Article 6), les procédures à employer sont d'abord spécifiées, puis illustrées par un

exemple en utilisant les résultats donnés dans l'Annexe D.

Il est supposé, dans la suite du présent article, que tous les résultats soit appartiennent à une distribution

normale unique, soit sont susceptibles d'être transformés en une telle distribution (voir 5.2). Les autres cas

(qui sont rares) nécessitent un traitement différent qui n'est pas dans l'objet de la présente Norme

internationale. Se reporter à la Référence [8] en Bibliographie pour l'essai statistique de normalité.

Bien que les procédures illustrées ici soient sous une forme permettant le calcul manuel, il est fortement

recommandé d'utiliser un calculateur électronique pour stocker et analyser les résultats des essais

interlaboratoires sur la base des procédures de la présente Norme internationale (voir [9] par exemple).

5.2 Transformation des données

5.2.1 Généralités

Dans de nombreuses méthodes d'essai, la fidélité dépend du niveau du résultat de l'essai, en sorte que la

dispersion des résultats diffère d'un échantillon à un autre. La méthode d'analyse décrite dans la présente

Norme internationale suppose qu'il n'en est pas ainsi, et la situation est corrigée, si nécessaire, par une

transformation.

Les écarts-types D des laboratoires et les écarts-types d des répétitions pour l’échantillon j (voir l’Annexe C)

j j

sont calculés et reportés dans des graphiques différents par rapport aux moyennes m des échantillons. Si les

j

courbes ainsi obtenues correspondent approximativement à deux droites parallèles à l'axe m, il n'est pas

nécessaire de procéder à une transformation. Mais si les points sont disposés approximativement suivant des

courbes de la forme D = f (m) et d = f (m), une transformation est nécessaire.

1 2

Les relations D = f (m) et d = f (m) ne sont généralement pas identiques. Les procédures statistiques de la

1 2

présente Norme internationale exigent toutefois que la même transformation soit applicable en même temps à

la répétabilité et à la reproductibilité. Pour cette raison, les deux relations sont combinées dans une relation

de dépendance unique, D = f(m) (où D inclut à présent d), en introduisant une variable fictive T. Cela tient

compte de la différence entre les relations, s'il y en a, et fournit un moyen de tester cette différence (voir F.1).

La relation simple D = f(m) est évaluée au mieux par une analyse de régression linéaire pondérée, même si

dans la plupart des cas une régression non pondérée constitue une approximation suffisante. La dérivation

des pondérations est décrite dans l'Article F.2 et la procédure de calcul pour l'analyse de régression est

décrite dans l'Article F.3. Des formes types de dépendance D = f(m) sont données dans l'Article E.1. Elles

sont toutes exprimées en fonction de paramètres de transformation B et B .

L'estimation de B et B et la procédure de transformation qui suit sont résumées dans l'Article E.2. Celui-ci

comporte les essais statistiques pour la signification de la régression (c'est-à-dire, savoir si la relation D = f(m)

est parallèle à l'axe m) et pour la différence entre les relations de répétabilité et de reproductibilité basées sur

une probabilité à 95 %. Si une telle différence est constatée, ou si aucune transformation appropriée n'existe,

les procédures alternatives échantillon par échantillon de l'ISO 5725-2 doivent être utilisées. En pareil cas, il

n’est pas possible de tester les biais de laboratoires de tous les échantillons (voir 5.6) ni d'évaluer la

composante d'interaction de variance (voir 6.2).

S'il apparaît, avec une probabilité de 95 %, qu'il existe une régression significative de la forme D = f(m), la

transformation adéquate y = F(x), où x est le résultat noté, est donnée par la formule:

dx

Fx =K (2)

()

∫

f x

()

où K est une constante. Dans ce cas, tous les résultats doivent être transformés en conséquence et le reste

de l'analyse exécuté en fonction des résultats transformés. Des transformations types sont données en E.1.

Le choix d'une transformation est difficile et ne peut faire l'objet de règles formelles. Une assistance statistique