EN 17371-2:2021

(Main)Provision of services - Part 2: Services contracts - Guidance for the design, content and structure of contracts

Provision of services - Part 2: Services contracts - Guidance for the design, content and structure of contracts

This document provides guidance on the design, content and structure of service contracts. It is aimed at service buyers and service providers entering a contractual relationship who do not necessarily have legal training. The guidance set out in this document does not constitute legal advice.

This document is applicable to:

a) service buyers and service providers regardless of type, size or the nature of the services;

b) service providers who may be inside or outside the service buyers' organization; and

c) any interested parties who are directly or indirectly involved in or affected by a procurement process.

This document is not applicable to service contracts where the service buyer is a consumer, nor for works contracts.

NOTE 1 "Works contracts" are contracts that have as their object the execution, or both the design and execution, of a work are not covered. Contracts having as their object only the design of a work are covered.

NOTE 2 "Work" means the outcome of building or civil engineering works taken as a whole which is sufficient in itself to fulfil an economic or technical function.

NOTE 3 "Consumer" means an individual member of the general public purchasing or using services for private purposes.

Dienstleistungserbringung - Teil 2: Dienstleistungsverträge - Leitlinien für die Gestaltung, Inhalt und Struktur von Verträgen

Dieses Dokument stellt eine Leitlinie für die Gestaltung, den Inhalt und die Struktur von Dienstleistungs-verträgen bereit. Es richtet sich an Dienstleistungskäufer und Dienstleister, die in ein Vertragsverhältnis eintreten und nicht unbedingt über eine juristische Ausbildung verfügen. Die in diesem Dokument dargelegte Leitlinie stellt keine Rechtsberatung dar.

Dieses Dokument ist anwendbar für:

a) Dienstleistungskäufer und Dienstleister, unabhängig vom Typ, Umfang oder der Art der Dienstleistungen;

b) Dienstleister, die innerhalb oder außerhalb der Organisation der Dienstleistungskäufer sein dürfen; und

c) alle interessierten Parteien, die direkt oder indirekt an einem Beschaffungsprozess beteiligt oder von diesem betroffen sind.

Dieses Dokument ist weder für Dienstleistungsverträge, in deren Rahmen der Dienstleistungskäufer ein Verbraucher ist, noch für Bauaufträge anwendbar.

ANMERKUNG 1 „Bauaufträge“ sind Verträge, die die Ausführung oder sowohl die Planung als auch die Ausführung eines Bauwerks zum Gegenstand haben, und werden in diesem Dokument nicht behandelt. Verträge, die nur die Gestaltung eines Bauwerks zum Gegenstand haben, werden abgedeckt.

ANMERKUNG 2 „Bauwerk“ bezeichnet das Ergebnis von Hoch- oder Tiefbauarbeiten insgesamt, das allein ausreicht, um eine wirtschaftliche oder technische Funktion zu erfüllen.

ANMERKUNG 3 „Verbraucher“ bezeichnet ein einzelnes Mitglied der Öffentlichkeit, das für Dienstleistungen zu privaten Zwecken zahlt oder diese nutzt.

Prestation de services - Partie 2 : Contrats de services - Recommandations pour l’élaboration, le contenu et la structure des contrats

Le présent document fournit des recommandations relatives à l’élaboration, au contenu et à la structure des contrats de services. Il est destiné aux acheteurs de services et aux prestataires de services s’engageant dans une relation contractuelle qui ne disposent pas nécessairement d’une formation juridique. Les recommandations exposées dans le présent document ne constituent en aucun cas un avis juridique.

Le présent document s’applique à :

a) tout acheteur de services et prestataire de services, quels que soient le type, la taille ou la nature des services ;

b) tout prestataire de services qui peut être interne ou extérieur à un organisme acheteur de services ; et

c) toute partie intéressée qui est directement ou indirectement impliquée dans, ou affectée par, un processus d’achat.

Le présent document ne s’applique pas aux contrats de services dans lesquels l’acheteur de services est un consommateur, ni aux marchés de travaux.

NOTE 1 Les « marchés de travaux » sont des contrats ayant pour objet soit l’exécution seule, soit à la fois la conception et l’exécution d’un ouvrage et ne sont pas couverts par le présent document. Les contrats ayant pour seul objet la conception d’un ouvrage sont couverts.

NOTE 2 Le terme « ouvrage » désigne le résultat d’un ensemble de travaux de construction ou de génie civil, suffisant en soi pour remplir une fonction économique ou technique.

NOTE 3 Le terme « consommateur » désigne un membre individuel du grand public qui achète ou utilise des services à des fins privées.

Zagotavljanje storitev - 2. del: Pogodbe o storitvah - Navodilo za oblikovanje, vsebino in strukturo pogodb

Ta dokument podaja navodilo za oblikovanje in strukturo pogodb o storitvah. Namenjen je kupcem in ponudnikom storitev, ki sklepajo pogodbeno razmerje in nimajo nujno pravne izobrazbe.

Ta dokument se lahko uporablja v vseh organizacijah ne glede na njihovo vrsto ali velikost.

Ta dokument se ne uporablja za pogodbe o storitvah, sklenjene med podjetji in potrošniki (B2C), oziroma javna naročila gradenj.

OPOMBA 1: »Javna naročila gradenj« so javna naročila, katerih predmet je izvedba ali projektiranje in izvedba gradnje, in v tem dokumentu niso zajeta. Javna naročila, katerih predmet je samo projektiranje gradnje, so zajeta v tem dokumentu.

OPOMBA 2: »Gradnja« pomeni zaključeno visoko ali nizko gradnjo kot celoto, ki je samozadostna pri izpolnjevanju svoje gospodarske ali tehnične funkcije.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 02-Nov-2021

- Withdrawal Date

- 30-May-2022

- Technical Committee

- CEN/TC 447 - Services - Procurement, contracts and performance assessment

- Drafting Committee

- CEN/TC 447/WG 1 - Contracts

- Current Stage

- 6060 - Definitive text made available (DAV) - Publishing

- Start Date

- 03-Nov-2021

- Due Date

- 09-May-2020

- Completion Date

- 03-Nov-2021

Relations

- Effective Date

- 28-Jan-2026

Overview

EN 17371-2:2021 is a CEN guidance standard for the design, content and structure of service contracts. It helps service buyers and service providers - including non-lawyers - create clear, practical contracts that define who does what, when and for what price. The standard provides structured, non-mandatory guidance (not legal advice) for business and public-sector procurement and excludes consumer contracts and works contracts (building/civil engineering execution).

Key Topics and Requirements

The standard groups contract content around business‑oriented themes and practical elements:

- Identification of contracting parties (clause 6.2)

- Clear naming, registration details and authorised signatories to avoid enforcement issues.

- Service scope and description (clause 6.3 & Annex A)

- How to specify, order and describe services so deliveries meet expectations.

- Service performance targets

- Use of key performance indicators (KPIs) and service levels to express obligations.

- Pricing and payment models (clause 6.4 & Annex B)

- Guidance on charge calculation, invoicing and common pricing approaches.

- Governing law and dispute resolution (clauses 6.5–6.6)

- Considerations for legal system choice and dispute handling mechanisms.

- Risk exposure and liabilities (clause 6.7)

- Defining limits, indemnities and insurance considerations.

- Intellectual property and service outputs (clause 6.8)

- Rights in deliverables and output ownership.

- Commencement, termination and exit management (clause 6.9 & Annex C)

- Contract start/stop, consequences and transition planning.

- Information and data considerations (clause 6.10)

- Data handling, confidentiality and related obligations.

- Change control and contract evolution (clause 6.11)

- Managing amendments, variations and governance.

- Practical structuring (clause 5)

- Use of frameworks, schedules, exhibits and attachments for complex contracts.

Applications

EN 17371-2 is practical for:

- Procurement professionals drafting service agreements

- SMEs and large service providers standardising contract templates

- Contract managers defining service levels, pricing and exit plans

- Public authorities and private organisations seeking harmonised guidance on contract structure, service specification, pricing models and exit management

It is sector-agnostic - applicable regardless of service type or organizational size - and helps improve clarity, reduce disputes and support consistent procurement outcomes.

Related Standards

- EN 17371-1: Service procurement phase (pre‑contract)

- EN 17371-3: Service execution phase (post‑contract)

Keywords: EN 17371-2:2021, service contracts, contract design, service procurement, service specification, service level, pricing models, exit management, CEN standard.

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

Great Wall Tianjin Quality Assurance Center

Established 1993, first batch to receive national accreditation with IAF recognition.

Hong Kong Quality Assurance Agency (HKQAA)

Hong Kong's leading certification body.

Innovative Quality Certifications Pvt. Ltd. (IQCPL)

Known for integrity, providing ethical & impartial Assessment & Certification. CMMI Institute Partner.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

EN 17371-2:2021 is a standard published by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN). Its full title is "Provision of services - Part 2: Services contracts - Guidance for the design, content and structure of contracts". This standard covers: This document provides guidance on the design, content and structure of service contracts. It is aimed at service buyers and service providers entering a contractual relationship who do not necessarily have legal training. The guidance set out in this document does not constitute legal advice. This document is applicable to: a) service buyers and service providers regardless of type, size or the nature of the services; b) service providers who may be inside or outside the service buyers' organization; and c) any interested parties who are directly or indirectly involved in or affected by a procurement process. This document is not applicable to service contracts where the service buyer is a consumer, nor for works contracts. NOTE 1 "Works contracts" are contracts that have as their object the execution, or both the design and execution, of a work are not covered. Contracts having as their object only the design of a work are covered. NOTE 2 "Work" means the outcome of building or civil engineering works taken as a whole which is sufficient in itself to fulfil an economic or technical function. NOTE 3 "Consumer" means an individual member of the general public purchasing or using services for private purposes.

This document provides guidance on the design, content and structure of service contracts. It is aimed at service buyers and service providers entering a contractual relationship who do not necessarily have legal training. The guidance set out in this document does not constitute legal advice. This document is applicable to: a) service buyers and service providers regardless of type, size or the nature of the services; b) service providers who may be inside or outside the service buyers' organization; and c) any interested parties who are directly or indirectly involved in or affected by a procurement process. This document is not applicable to service contracts where the service buyer is a consumer, nor for works contracts. NOTE 1 "Works contracts" are contracts that have as their object the execution, or both the design and execution, of a work are not covered. Contracts having as their object only the design of a work are covered. NOTE 2 "Work" means the outcome of building or civil engineering works taken as a whole which is sufficient in itself to fulfil an economic or technical function. NOTE 3 "Consumer" means an individual member of the general public purchasing or using services for private purposes.

EN 17371-2:2021 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 03.080.01 - Services in general. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

EN 17371-2:2021 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to EN ISO 8437-4:2021. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

EN 17371-2:2021 is associated with the following European legislation: Standardization Mandates: M/517. When a standard is cited in the Official Journal of the European Union, products manufactured in conformity with it benefit from a presumption of conformity with the essential requirements of the corresponding EU directive or regulation.

EN 17371-2:2021 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-januar-2022

Zagotavljanje storitev - 2. del: Pogodbe o storitvah - Navodilo za oblikovanje,

vsebino in strukturo pogodb

Provision of services - Part 2: Services contracts - Guidance for the design, content and

structure of contracts

Dienstleistungserbringung - Teil 2: Dienstleistungsverträge - Leitlinien für die Gestaltung,

Inhalt und Struktur von Verträgen

Prestation de services - Partie 2 : Contrats de services - Recommandations pour

l’élaboration, le contenu et la structure des contrats

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: EN 17371-2:2021

ICS:

03.080.01 Storitve na splošno Services in general

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

EN 17371-2

EUROPEAN STANDARD

NORME EUROPÉENNE

November 2021

EUROPÄISCHE NORM

ICS 03.080.01

English Version

Provision of services - Part 2: Services contracts - Guidance

for the design, content and structure of contracts

Prestation de services - Partie 2 : Contrats de services - Dienstleistungserbringung - Teil 2:

Recommandations pour l'élaboration, le contenu et la Dienstleistungsverträge - Leitlinien für die Gestaltung,

structure des contrats Inhalt und Struktur von Verträgen

This European Standard was approved by CEN on 21 June 2021.

CEN members are bound to comply with the CEN/CENELEC Internal Regulations which stipulate the conditions for giving this

European Standard the status of a national standard without any alteration. Up-to-date lists and bibliographical references

concerning such national standards may be obtained on application to the CEN-CENELEC Management Centre or to any CEN

member.

This European Standard exists in three official versions (English, French, German). A version in any other language made by

translation under the responsibility of a CEN member into its own language and notified to the CEN-CENELEC Management

Centre has the same status as the official versions.

CEN members are the national standards bodies of Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia,

Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway,

Poland, Portugal, Republic of North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and

United Kingdom.

EUROPEAN COMMITTEE FOR STANDARDIZATION

COMITÉ EUROPÉEN DE NORMALISATION

EUROPÄISCHES KOMITEE FÜR NORMUNG

CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Rue de la Science 23, B-1040 Brussels

© 2021 CEN All rights of exploitation in any form and by any means reserved Ref. No. EN 17371-2:2021 E

worldwide for CEN national Members.

Contents Page

European foreword . 3

Introduction . 4

1 Scope . 5

2 Normative references . 5

3 Terms and definitions . 5

4 Purpose of a service contract . 6

5 Service contract structures . 6

6 Content of a service contract . 7

6.1 General. 7

6.2 Who is entering into the service contract? . 7

6.3 What are the services – how are they specified, ordered and what are the service

performance targets? . 8

6.4 How are charges calculated and paid? . 13

6.5 What legal system governs the service contract? . 16

6.6 How will the contracting parties deal with disputes? . 16

6.7 What is the exposure? . 17

6.8 What intellectual property rights are there in, and to, the service outputs? . 18

6.9 When does the agreement commence, how is it terminated and what are the

consequences of termination? . 19

6.10 What considerations relate to information/data? . 20

6.11 Making changes to the agreement and the contracting parties’ relationship . 21

6.12 What other terms need to be considered? . 22

Annex A (informative) Service scope and description . 25

Annex B (informative) Pricing models . 28

Annex C (informative) Exit management . 30

Bibliography . 33

European foreword

This document (EN 17371-2:2021) has been prepared by Technical Committee CEN/TC 447 “Horizontal

standards for the provision of services”, the secretariat of which is held by BSI.

This European Standard shall be given the status of a national standard, either by publication of an

identical text or by endorsement, at the latest by May 2022, and conflicting national standards shall be

withdrawn at the latest by May 2022.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. CEN shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

This document has been prepared under a Standardization Request given to CEN by the European

Commission and the European Free Trade Association.

Any feedback and questions on this document should be directed to the users’ national standards body.

A complete listing of these bodies can be found on the CEN website.

According to the CEN-CENELEC Internal Regulations, the national standards organisations of the

following countries are bound to implement this European Standard: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia,

Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland,

Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of North

Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the United

Kingdom.

Introduction

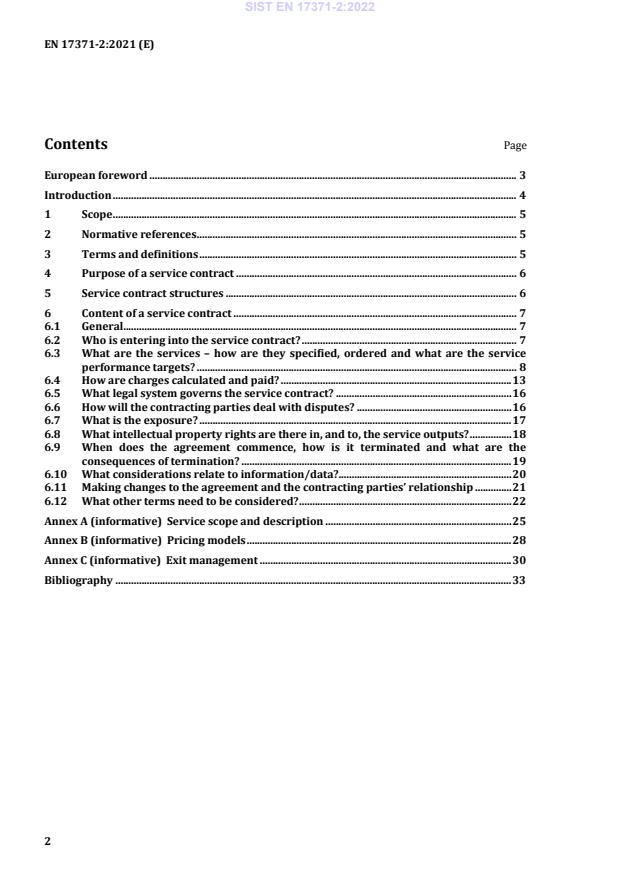

This document is part of a series of European Standards that address different phases in the provision of

services (see Figure 1): the service procurement phase (EN 17371-1), the service contracting phase

(EN 17371-2) and the service execution phase (EN 17371-3).

Each part of the series can be used individually or in combination with the other parts.

Figure 1 — Phases in the provision of services

The drafting of the series was initiated after CEN presented the findings of a study on the potential and a

possible impact of horizontal service standards on the EU single market for services. This study was as a

response to mandate M/517 from the European Commission for programming and development of

horizontal service standards. The objective of this mandate was to encourage the development of

voluntary European Standards covering issues common to many service sectors. Such standards should

aim to facilitate compatibility between service providers and improve information and the quality of

services to the recipient.

This document addresses the service contracting phase and has been developed to provide organizations

with guidance on the design, content and structure of service contracts. No part of this document is

intended to be mandatory for inclusion in a service contract; rather it is structured to enable

organizations entering into a service contract to identify the solution best suited to achieve the intended

business outcomes. The guidance lists the key contents of a service contract that organizations might

consider as part of the broader solution being contracted. Based on the nature of services being

contracted, the service buyer and service provider can decide upon the specific content for their service

contract. This document does not provide guidance regarding the applicable legal rules and regulations.

1 Scope

This document provides guidance on the design, content and structure of service contracts. It is aimed at

service buyers and service providers entering a contractual relationship who do not necessarily have

legal training. The guidance set out in this document does not constitute legal advice.

This document is applicable to:

a) service buyers and service providers regardless of type, size or the nature of the services;

b) service providers who may be inside or outside the service buyers' organization; and

c) any interested parties who are directly or indirectly involved in or affected by a procurement

process.

This document is not applicable to service contracts where the service buyer is a consumer, nor for works

contracts.

NOTE 1 “Works contracts” are contracts that have as their object the execution, or both the design and execution,

of a work are not covered. Contracts having as their object only the design of a work are covered.

NOTE 2 “Work” means the outcome of building or civil engineering works taken as a whole which is sufficient in

itself to fulfil an economic or technical function.

NOTE 3 “Consumer” means an individual member of the general public purchasing or using services for private

purposes.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references in this document.

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

• IEC Electropedia: available at https://www.electropedia.org/

• ISO Online browsing platform: available at https://www.iso.org/obp

3.1

contracting parties

contracting party

service buyer and service provider which conclude a service contract

Note 1 to entry: Each service buyer/provider is considered a contracting party.

3.2

service buyer

organization that buys services from a service provider

Note 1 to entry: In public procurement, the service buyer may also be known as the contracting authority/entity.

3.3

service contract

agreement between a service buyer and service provider setting out their legally binding rights and

obligations for the provision of services

3.4

service performance target

target level of a key performance indicator to express the need, expectation, or obligation of service buyer

3.5

service provider

organization that offers or delivers one or more services

4 Purpose of a service contract

Service contracts form legally binding agreements between the service buyer and service provider that

enter into them and have the key purpose of providing clarity on who is ordering a service, who is

providing the service, what service should be provided, where and when and for what remuneration. The

service contract should be in writing, as well as dated and signed by the service buyer and the service

provider.

What a “good” service contract looks like will vary depending on the circumstances (in most situations

there is no such thing as a “standard contract”). The contracting parties should strive to ensure that

whatever clauses are included in the service contract, those clauses are drafted using straightforward,

clear and concise wording. The service contract should aim to be as short as possible but as long as is

necessary.

5 Service contract structures

It is important that the necessary contents of a service contract are brought together into a clear

structure. While there are certain basic elements that should be present in all service contracts (as

mentioned in Clause 4 above), the length and structure may vary considerably.

Service contracts based on common law systems (such as English law) tend to be longer than in civil law

systems (like much of the rest of Europe) as few provisions are implied by law therefore the service

contract tends to be more comprehensive in setting out all of the terms which will govern the supply of

services. In civil law systems much of the law is codified and will apply to contracts they govern unless

otherwise specified.

The service contract may take the form of a framework which provides a structure and mechanism for

ordering and providing services from time to time on the terms established under the service contract.

Often this mechanism involves completing a template document to the service contract which sets out,

within the terms under the framework, the specific services, specifications and obligations in respect of

the services, service standards, economics and other considerations that determine and impact the

delivery of services.

In order to keep larger and more complex service contracts easier to read and manageable, specific

elements of the service contract are often dealt with in schedules, exhibits or attachments to the main

agreement such as with lengthy service descriptions, service level and credit mechanisms or charging

mechanisms.

There is no fixed rule on which party will establish the basis of the service contract. In some cases, it may

be established by the service buyer possibly through and as part of the service procurement process

(see EN 17371-1) while in other cases it may be established by the service provider.

6 Content of a service contract

6.1 General

This Clause provides an overview of the key content that may be found in a service contract, their function

and purpose.

In order to enable the contracting parties to approach discussions from a business-orientated standpoint,

the contractual content to be considered has been grouped under the following themes:

— Who is entering into the service contract? (subclause 6.2);

— What are the services – how are they specified, ordered and what are the service performance

targets? (subclause 6.3);

— How are charges calculated and paid? (subclause 6.4);

— What legal system governs the service contract? (subclause 6.5);

— How will the contracting parties deal with disputes? (subclause 6.6);

— What is the exposure? (subclause 6.7);

— What rights are there in and to the service outputs? (subclause 6.8);

— When does the agreement commence, how is it terminated and what are the consequences of

termination? (subclause 6.9);

— What considerations relate to information/data? (subclause 6.10);

— Making changes to the agreement and the contracting parties’ relationship (subclause 6.11);

— What other terms need to be considered? (subclause 6.12).

6.2 Who is entering into the service contract?

In general, the obligations, rights and remedies under a service contract will apply to, and be enforceable

by, only the contracting parties to such agreement. Therefore, it is important to clearly identify which

legal entities are entering into the service contract.

Where the contracting parties are not identified or are not correctly or sufficiently identified, then there

is a risk that the service contract is either not enforceable or that it is enforceable but against an

unintended party. This could happen, for example, where one of the contracting parties is referred to as

XYZ and is a member of a group of companies with similar names, meaning it is not clear if the contracting

party refers to XYZ the subsidiary company or XYZ the parent company.

Service contracts should clearly identify the contracting parties to such service contract. To do this it is

useful to include any registration details such as a company registration number or registered office

where these are listed in an official database e.g. Companies House for English registered companies, the

German Commercial Register for German registered companies or the Registre de Commerce et des

Sociétés for French companies.

If there are more than two parties entering into the service contract (for example, more than one entity

on the service buyer or service provider side) then each additional party should be specified and thought

should be given as to which terms will apply to which parties. This document assumes there are two

parties to the service contract, the service buyer and service provider.

The service contract signed on behalf of an organization should be signed by authorized representatives

of the contracting parties and identified in the service contract.

6.3 What are the services – how are they specified, ordered and what are the service

performance targets?

6.3.1 Service description

A fundamental element of the service contract is the service scope and description which defines the

services which are being sourced by the service buyer from the service provider. In service contracts

developed by the contracting parties in a collaborative manner with the intent of building a positive

relationship, the service buyer specifies what it wants and shifts the responsibility of determining how

the work gets delivered to the service provider. Whilst this is a general principle, it should be

remembered that in the context of some services being contracted, the contracting parties need to

consider if there is a need for a detailed description of how the services are provided or whether the focus

should be on the composition of services being provided. In either context it is very important for

contracting parties to spend time to get this part correct as this would determine the services that

eventually get delivered by the service provider, not just what gets delivered but also its efficiency,

effectiveness and future transformation.

For each service being delivered the contracting parties should consider which party is responsible for

meeting the requirements, what they are required to do, where it should be done, by when and (where

relevant) in what manner (the who, what, where, when and how) and then detail this in the service

contract.

Annex A provides considerations to be kept in mind while designing the service scope and description.

6.3.2 Transition and transformation during the provision of services

For some service contracts there may be a need for an initial transfer of people, assets and/or processes

from either the service buyer or the incumbent service provider being replaced. Once such transition

activities have been completed, the incoming service provider would then be able to commence with the

supply of services to the service buyer.

Transformative activities entail making changes to the provision of such services so what the service

buyer then receives will be different to what was being supplied previously.

Where such activities are required within the scope of the service contract, the contracting parties may

consider:

— What the scope of such services are (see subclause 6.1).

— What the output or deliverables of the services are.

— When such activities should be completed by i.e. a milestone date.

— What the consequences of failing to reach such a milestone would be (termination, liquidated

damages, etc.).

6.3.3 Mechanism for ordering services

This subclause addresses the theme of how the service contract allows the service buyer to order

services.

Along with a description of the services being provided, the contracting parties should consider whether

the service contract needs to set out a process for how the services will be ordered throughout its

duration. For some service contracts it may be appropriate for all services to be provided from the date

the service contract becomes effective, while for others the supply of services may only be needed on a

project-by-project basis in which case the service contract should specify the mechanism for ordering

such services.

Another consideration which should be addressed in the service contract if applicable is whether group

companies of the contracting parties entering into the service contract may order and supply services

under the terms of the service contract using the same mechanism.

6.3.4 Service performance targets

6.3.4.1 General

EN 17371-3 provides guidance and a model for defining a service measurement structure to facilitate

service monitoring, measurement analysis and evaluation.

Service performance management is an important element in service contracts to ensure the robust and

efficient management of performance of services agreed between the contracting parties. In keeping with

the spirit of building a relational contract, this element is aimed at a collaborative exercise between the

contracting parties to achieve the desired performance levels. The allocation of responsibility outlined in

subclause 6.3.1 forms the basis for this element by outlining the performance levels expected of the

service provider on the assumption that the service buyer discharges its obligations.

Service performance management should be viewed as a means to provide insight into service delivery

and to drive continuous improvement. Too much emphasis on a large set of metrics could drive focus

towards the minutiae, losing sight of the bigger picture.

Cost and effort are also expended in tracking, measuring, collating and reporting performance metrics so

this effort should be focused on key metrics.

The service management framework in the service contract should be based on the following principles:

• Provide a comprehensive framework to measure end-to-end process performance;

• Align service metrics with the desired business outcomes;

• Establish transparent and clear allocation of responsibility and accountability for service delivery

between the service buyer and service provider;

• Establish governance protocols (including financial mechanisms) embedded in the service

management framework to ensure continuous performance review, ongoing course correction and

service improvement;

• Provide stability in service performance;

• Provide visibility and transparency of service performance to all stakeholders; and

• Drive behaviour to actively move service performance targets to higher global performance levels

over the life of the service contract.

6.3.4.2 Service performance metrics

6.3.4.2.1 Definition

Service performance metrics are indicators of the performance of services being delivered as part of the

service contract, including both those delivered by the service provider and the end-to-end service

activities retained by the service buyer.

The process of designing these metrics is covered in EN 17371-3. Once identified, the service

performance management mechanism to be included in the service contract should consider the

following:

— What is the service or event being measured?

— Over what period of time are the measurements to be assessed (daily, weekly, monthly, annually)?

— What is the standard of performance to be achieved e.g. 98 % of service availability?

— Will there be a burn-in period where the parties collect data and agree on a realistic baseline for

measurement? (see 6.3.4.3)

— Are there any exclusions from such measurements e.g. downtime of a platform while routine

maintenance takes place?

— Which party will measure and report against the service performance targets and how often?

— How can the contracting parties modify, add or remove any service performance targets over time?

— What is the impact of failing to meet a service performance target?

— If financial penalties (also termed service credits) apply, will they be deducted immediately or upon

request?

— Is there a cap on the amount of service credits?

— Are service credits the sole and exclusive remedy for a service performance target failure or are they

in addition to other rights (including termination)?

6.3.4.3 Data collection and baseline process

It is very important for the service contract to include baseline measurements for all metrics including

volume metrics. The importance of the baseline lies in being the starting point for all future

measurements over the term of the service contract. The baselines should be agreed by the contracting

parties using the agreed measurement definition and methodology. It is advisable for both contracting

parties to consider the need for undertaking a baseline exercise. While it may be expedient in the short

term, it can have significant adverse effect over the term of the service contract. Hence it is a decision that

should not be taken lightly.

Further, it is also important to agree and document in the service contract the baselining methodology.

For example, to arrive at a baseline for a metric measured monthly, would six months data suffice or 12

months, how would data outliers be handled etc.? Baselining is not just a one-off activity to be performed

at the start of the service contract but would need to be undertaken during the term of the service

contract should a new metric be introduced.

In some instances, historical data may not be available, either at the commencement of the service

contract or during its term. To address this situation, service contracts use a concept known as a

“Burn-In period” to enable the contracting parties to track and measure the metric for an agreed length

of time. At the end of this period, the contracting parties agree to a baseline derived from the

measurements during this period.

Some service contracts suspend the service penalty in respect of service performance metrics within the

duration of the burn-in period.

6.3.4.4 Governance of service performance management

6.3.4.4.1 General

Governance of service performance management relates to the way the contracting parties would

manage on-going service performance through the service performance management framework. It

comprises:

— Performance measurement and reporting;

— Service monitoring and review;

— Actions when service performance targets are not met;

— Changes to service metrics.

6.3.4.4.2 Performance measurement reporting

The service contract should specify the performance measurement and reporting obligations of the

service provider.

6.3.4.4.3 Service monitoring and review

Service performance should be monitored and reviewed by the contracting parties as per the protocols

established under the governance structure of the service contract.

6.3.4.4.4 Actions when service performance targets are not met

6.3.4.4.4.1 General

Over the term of the service contract, it is likely that the service provider may not achieve all service

performance targets as measured by service metrics. The service performance management framework

should clarify actions and implications of the service provider’s failure to meet agreed service standards.

Service contracts follow a two-step process to address this situation:

a) Root cause analysis and remediation plan;

b) Financial service credits.

6.3.4.4.4.2 Root cause analysis and remediation plan

When a service performance target is missed, the first action is for the service provider to perform a root

cause analysis to identify the source of the failure and obtain the service buyer’s approval. Along with

identifying the root cause for failure, the service provider should develop a remediation plan and

implement actions to remediate.

6.3.4.4.4.3 Financial service credits

The root cause for failure could lie entirely upon the service provider, or on the side of the service buyer

or a combination of the two.

For failures due to the service provider, service contracts often couple service performance targets with

service credits (either a fixed sum or expressed as a percentage of the service fees) as a mechanism to

penalize failures to achieve agreed service performance targets. Service credits are sometimes seen as a

blunt instrument to drive the right behaviour from the service provider but are still commonly used,

particularly in an outsourcing agreement.

6.3.4.4.5 Incurrence of service credits

Service contracts typically identify service metrics that are subject to an obligation for the service

provider to pay the service buyer a service credit if these metrics do not meet agreed service performance

targets. This obligation occurs only when the failure to meet agreed service performance targets is

entirely due to factors caused by the service provider. If the service provider fails to meet the agreed

service performance targets due to the service buyer organization, then the principle of fairness demands

that the service provider is excused of its obligation due to the failure to meet service performance

targets.

The intent of a service credit mechanism is not to place unreasonable burdens upon the service provider.

The typical construct of a service credit mechanism comprises the following:

— Amount at risk: Usually computed as a percentage of service charges corresponding to the reporting

period of the metric. For example, if the metric is measured and reported monthly, then the amount

at risk is computed as a percentage of the monthly service charges.

— Percentage amount at risk allocated to the metric – Service Metric Weight: Where there are multiple

service metrics being measured and subject to service credits, each metric is accorded a specific

weight. The weight reflects the relative importance of the metric within the broader portfolio.

— Service credit is then computed by multiplying the amount at risk by the Service Metric Weight.

In some service contracts, the concept of service weights is done away with, rather applying a standard

weight to all service metrics or by equating the service credit to a flat percentage of service charges.

Irrespective of the construct of the service credit mechanism, it needs to be recognized that in relational

service contracts the focus of the contracting parties needs to be on improvement and learning from

failures. Emphasis needs to be on remedying the failure and to initiate actions to prevent their recurrence.

6.3.4.5 Changes to service metrics

As the business evolves over the term of the service contract, it may become essential to modify the

original set of service metrics. It is advisable that service metrics are changed using the Contract Change

Control process. The process should follow the same steps as at the start of the service contract.

In line with the spirit of continually creating economic value over the term of the service contract, many

relational service contracts have a provision to automatically increase service performance targets each

year of the service contract. The methodology for the annual automatic increase is included in the service

contract and hence does not require the Contract Change process to record annual changes.

6.3.5 Business continuity and disaster recovery planning

6.3.5.1 The purpose

Where the services bring provided are business critical to the service buyer and any disruption to their

supply would have a material impact on the service buyer then it may be appropriate to require the

service provider to have in place and maintain a business continuity and disaster recovery plan (BC and

DR plan) describing the processes and procedures to be followed in the event of a disaster and/or

unexpected event.

The aim of such an obligation is to ensure the service provider is able to recover from a disaster and/or

unexpected event and resume operations within a suitable timeframe to minimize the impact of the

supply of services to the service buyer. The ability to minimize the effects of a disaster and/or unexpected

event is often preferable to having contractual remedies (such as damages) for a failure to provide those

affected services.

6.3.5.2 Contents of a business continuity and disaster recovery plan

A business continuity and disaster recovery plan should comprise the following elements:

— Business impact analysis — risk assessment to identify key services or aspects of services and sites

that may be affected, and the risks associated;

— Establishment of crisis management teams (service buyer and service provider) and contact details

to be notified in the event of a disaster and/or unexpected event;

— Roles and responsibilities of each, service buyer and service provider, under the BC and DR plan;

— Timescales for implementing the BC and DR plan;

— Back-up process and elements of the configuration;

— List of equipment and technology infrastructure to be provided by service provider in the event of a

disaster and/or unexpected event;

— Testing process and schedule;

— Training programme for both service buyer and service provider personnel;

— Governance process to documenting changes and updating the BC and DR plan.

6.4 How are charges calculated and paid?

6.4.1 General

This subclause addresses the question of how the contracting parties structure and manage the

economics of the service contract over its term. Across the different contract elements, this remains one

of the most contested and debated, not just during the initial negotiations but over the life of the service

contract. Disagreements between the contracting parties on pricing have led to the collapse of

negotiations, with the service buyers having to restart discussions with a new service provider.

Ensuring the economics of the service contract is correct is critical for the success of the relationship,

both from the point of meeting the objectives and intent, and to facilitate the creation of a positive and

healthy relationship between the two contracting parties. Whilst it is essential for each side to arrive at a

deal that is best for them, most contracting relationships fail to achieve this objective. Some of the reasons

for this are:

i. Fair return

For contractual relationships to be successful, it is essential that both sides earn a fair return to allow for

investments to transform, adapt and enhance the relationship. Service contracts whose economic models

are designed to drive to lowest costs often fail to create either the right behaviour or financial incentives

to grow and adapt, ultimately failing to meet the intended objectives.

In summary, it is essential for contracting parties to build an economic model that allows for a fair return

for both sides, creates flexibility to adapt to evolving business conditions, ensures transparency and

enables a healthy relationship to be built.

ii. Service contracts are uncertain

Service contracts are designed on the assumption that it is possible to identify and price all possible

scenarios for costs and revenue over the term of the service contract. Following on from this assumption

each side believes it can with a high degree of certainty compute the “best financial deal” for them at the

point of contracting.

The reality is that the future is uncertain and attempting to create a deterministic view of events is flawed;

there is a higher probability of being incorrect and the “precise” financials wrong at best. Attempting to

create a service contract with “all in financials” agreed up front is a wrong way to approach developing

service contracts.

Contract uncertainty is becoming more of an issue in an environment of fast evolving technology that

impact the way services are delivered and consumed. In a time when organizations are rapidly

reimagining the services they deliver to their customers, and technologies like automation, cognitive, AI,

mobility, cloud, and growing computer power are transforming delivery models, designing service

contracts on an assumption of a certain future is incorrect and flawed.

iii. Unfair risk allocation

All service contracts have inherent risk associated with the business and the relationship. During

negotiations, it is inevitable that the party with a greater bargaining power tends to shift risk to the other

side. Whilst this is only to be expected, problems arise when one side is forced to assume

disproportionate levels of risk. Many failed service contracts display a similar pattern. Service buyers,

because of their great bargaining power at the point of contracting, shift a significant proportion of risk

to service providers to arrive at their “best deal”. Over the term of a service contract, this unfair risk

allocation reduces the ability and flexibility of the service provider to adjust services to evolving business

environmental conditions. The adverse impact on the service provider is undoubtedly harsh, but

perversely, service buyers who believed they had the “best deal” are also hurt as service providers can

no longer deliver services to meet the emerging business needs of the service buyer, leaving the service

buyer stuck with services that are misaligned to business demands.

iv. Pricing for the unknown

Another common fallacy in service contracts is to attempt to price the unknown. Service buyers often

require service providers to price into the service contract transformation programmes and initiatives

that are yet to be conceptualised by service buyers themselves. With no economic basis to price, service

providers take a shot in the dark including buffers to mitigate against all type of eventualities. The

resultant price is a figure that is a figment of the service buyer’s imagination obscured by layers of risk

mitigation price elements. Whilst both contracting parties may have the satisfaction of developed a

comprehensive price, over time all this serves to achieve is lowered trust and transparency.

6.4.2 Charges/remuneration for services

There are several economic models to choose from, each being differentiated by the basic pricing element.

Examples of pricing models for service contracts can be found in Annex B.

6.4.3 Payment terms

Payment terms are a key element of the overall economic model. Typically, payments in service contracts,

are aligned to the business cycle. However, quite often service buyers align payment terms on service

contracts to their standard payment terms e.g. 30 days. It needs to be recognized that payment terms

offer an area of negotiation for both contracting parties and can be customized to suit the specific

requirements of the service contract. The EU adopted Directive 2011/7/EU to combat late payment in

commercial transactions and imposes time limits in which organizations have to pay their invoices. Some

EU countries have imposed stricter time limits so this should be assessed by the contracting parties in

accordance with the governing law of the service contract.

6.4.4 Taxation

Tax is an important consideration for service contracts. For cross border service contracts complex tax

issues may arise.

The contracting parties should determine what taxes could apply to the supply of services under the

service contract. These could be, for example, whether there will be sales taxes such as VAT (value added

tax), withholding taxes or otherwise. Once this is understood, the contracting parties should consider

whether to include any provisions regarding the applicability of such taxes, how potential liabilities

should be dealt with and whether the contracting parties will work together to achieve the most tax

efficient structure for the service contract under applicable laws.

For service contracts where VAT is applicable to the supply of services it is common for the service

contract to clarify that the charges are exclusive of VAT (unless the contracting parties have agreed

alternative commercial arrangements).

6.4.5 Price adjustment mechanisms — inflation, foreign exchange rates, benchmarking

During the term of a service contract, circumstances could arise which mean that the charges agreed at

execution of the service contract are no longer acceptable to one or both contracting parties. These

changes could be due to factors which are outside of the contracting parties’ control or influence such as

changes in foreign exchange rates or inflation (or both) or they could be due to other external factors

such as developments in technology which significantly decrease (or in some cases increase) the service

provider’s costs to provide the services. Where such risk exists, the contracting parties may agree

mechanisms in the service contract for adjusting the price.

Taking foreign exchange as an example, where the contracting parties are located in different countries

with different currencies and they specify one of those currencies in the service contract for payment of

the charges, one of the contracting parties would benefit while the other would suffer in the event of

foreign exchange rate fluctuations.

Where the service provider is located in a country which is prone to high inflation the service provider

may also make the case for the charges to rise in line with a published inflation index. They may be

national laws which limit the use of price index clauses, including for service contracts.

Benchmarking is a mechanism included in some service contracts with a long term to investigate whether

the services are being supplied at a price and at service performance targets which are competitive in the

market. A benchmarking exercise is a process whereby the services under the contract are compared,

usually by an independent third party, against similar services supplied by competitors of the service

provider in order to determine their competitiveness. The service buyer and service provider can specify

in the service contract what outcome (if any) there will be where a benchmarking exercise has been

conducted.

6.5 What legal system governs the service contract?

It is advisable to specify in any service contract which governing law will apply to it. The governing law

chosen will determine all questions in relation to the validity, interpretation, effect

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...