CEN/TR 17828:2022

(Main)Road infrastructure - Automated vehicle interactions - Reference Framework Release 1

Road infrastructure - Automated vehicle interactions - Reference Framework Release 1

This document provides the current road equipment suppliers’ visions and their associated short term and medium-term priority deployment scenarios. Potential functional/operational standardization issues enabling a safe interaction of road equipment/infrastructure with automated vehicles in a consistent and interoperable way are identified. This is paving the way for a deeper analysis of standardization actions which are necessary for the deployment of priority short-time applications and use cases.

This deeper analysis will be done at the level of each priority application/use case by identifying existing standards to be used, standards gaps/overlaps and new standards to be developed to support this deployment.

The release 1 is focusing on short-term (2022 to 2027) and medium-term deployment. Further releases will update this initial vision according to short term deployment reality.

The objectives of this document are to:

- Support the TC 226 and its WG12 work through the development of a common vision of the roles and responsibilities of a modern, smart road infrastructure in the context of the automated vehicle deployment from SAE level 1 to SAE level 5. The roles and responsibilities of the road infrastructure are related to its level of intelligence provided by functions and data being managed at its level.

- Promote the road equipment suppliers and partners visions associated to their short-term and medium- term priorities to European SDOs and European Union with the goal of having available relevant, consistent standards sets enabling the identified priority deployment scenarios.

NOTE Road equipment/infrastructure includes the physical reality as its digital representation (digital twin). Both need to present a real time consistency.

Straßeninfrastruktur - Bezugsrahmen für die Interaktion automatisierter Fahrzeuge

Interactions Infrastructure routière - Véhicule automatisé : Cadre de reference

Le présent document présente les visions actuelles des fournisseurs d’équipements de la route et leurs scénarios de déploiement prioritaires à court et moyen terme associés. Les problèmes potentiels liés à la normalisation fonctionnelle / opérationnelle permettant des interactions sûres entre les équipements de la route / l’infrastructure routière et les véhicules automatisés de manière cohérente et interopérable sont identifiés. Cela ouvre la voie à une analyse plus approfondie des actions de normalisation nécessaires au déploiement d’applications et de cas d’utilisation prioritaires à court terme.

Cette analyse plus approfondie sera réalisée au niveau de chaque application/cas d’utilisation prioritaire en identifiant les normes existantes à utiliser, les lacunes / recoupements des normes et les nouvelles normes à élaborer pour accompagner ce déploiement.

La version 1 est axée sur le déploiement à court terme (2022 à 2027) et moyen terme. D’autres versions mettront à jour cette vision initiale en fonction de la réalité du déploiement à court terme.

Les objectifs de ce rapport technique sont les suivants :

Soutenir le comité technique TC 226 et son groupe de travail WG12 dans le développement d’une vision commune des rôles et des responsabilités d’une infrastructure routière moderne et intelligente dans le contexte du déploiement des véhicules automatisés de niveaux SAE 1 à 5. Les rôles et responsabilités de l’infrastructure routière sont liés au niveau d’intelligence que lui confèrent les fonctions et les données gérées à son niveau.

Promouvoir les visions des partenaires et fournisseurs d’équipements de la route associées à leurs priorités à court et moyen terme auprès des SDO européens et de l’Union européenne dans le but de disposer d’ensembles de normes pertinents et cohérents permettant la mise en œuvre des scénarios de déploiement prioritaires identifiés.

Note : Les équipements de la route et l’infrastructure routière comprennent la réalité physique sous la forme de sa représentation numérique (jumeau numérique). Les deux doivent présenter une cohérence en temps réel.

Cestna infrastruktura - Avtomatizirane interakcije vozil - Referenčni okvir, različica 1

Ta dokument podaja trenutne vizije dobaviteljev opreme za ceste ter njihove kratkoročne in srednjeročne prednostne scenarije uvajanja, povezane s tem. Opredeljene so potencialne težave s funkcionalno/operativno standardizacijo, ki omogoča varno interakcijo med opremo za ceste/cestno infrastrukturo in avtomatiziranimi vozili na skladen in interoperabilen način. To omogoča za izčrpnejšo analizo standardizacijskih ukrepov, ki so potrebni za uvedbo prednostnih kratkoročnih aplikacij in primerov uporabe.

Ta izčrpnejša analiza bo opravljena na ravni vsake prednostne aplikacije/primera uporabe z opredelitvijo obstoječih standardov, ki jih je treba uporabiti, vrzeli/prekrivanja standardov in novih standardov, ki bi jih bilo treba razviti za podporo pri tem uvajanju.

1. izdaja se osredotoča na kratkoročno (2022–2027) in srednjeročno uvajanje. Nadaljnje izdaje bodo prvotno vizijo posodobile ob upoštevanju dejanskega poteka kratkoročnega uvajanja.

Namen tega dokumenta je:

– podpreti TC 226 in delo povezane skupine WG12 z oblikovanjem skupne vizije vlog in odgovornosti sodobne, pametne cestne infrastrukture v kontekstu uvajanja avtomatiziranih vozil od stopnje SAE 1 do stopnje SAE 5. Vloge in odgovornosti cestne infrastrukture so povezane z njeno stopnjo inteligence, ki jo zagotavljajo funkcije in podatki, ki se upravljajo na njeni ravni;

– spodbujati vizije dobaviteljev opreme za ceste in partnerjev, povezane z njihovimi kratkoročnimi in srednjeročnimi prednostnimi nalogami, pri evropskih organizacijah za razvoj standardov in Evropski uniji, da bi zagotovili ustrezne in dosledne sklope standardov, ki bi omogočili razvoj opredeljenih prednostnih scenarijev uvajanja.

OPOMBA: Oprema za ceste/cestna infrastruktura vključuje fizično realnost kot digitalni prikaz (digitalni dvojček). Oboje mora biti usklajeno v realnem času.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 21-Jun-2022

- Technical Committee

- CEN/TC 226 - Road equipment

- Drafting Committee

- CEN/TC 226/WG 12 - Road interaction - ADAS / Autonomous vehicles

- Current Stage

- 6060 - Definitive text made available (DAV) - Publishing

- Start Date

- 22-Jun-2022

- Due Date

- 20-Aug-2021

- Completion Date

- 22-Jun-2022

Overview

CEN/TR 17828:2022 - Road infrastructure: Automated vehicle interactions (Reference Framework Release 1) defines a common vision and pre‑standardization roadmap for how modern, smart road infrastructure should interact with automated vehicles. Focused on short‑term (2022–2027) and medium‑term deployments, this CEN technical report captures road equipment suppliers’ priorities, identifies potential standardization issues, and paves the way for deeper analysis of standards needed to enable safe, consistent and interoperable interactions between infrastructure and vehicles (SAE levels 1–5). The document explicitly treats the physical road environment and its digital twin as needing real‑time consistency.

Key topics

- Roles & responsibilities of road infrastructure versus vehicle systems, tied to the infrastructure’s level of intelligence and data management.

- Operational Design Domain (ODD) considerations for infrastructure‑assisted automation.

- Functional distribution and interaction modes: cooperative, model‑based, fusion and autonomous safety interactions between roadside equipment and vehicle ADAS.

- Functional safety & redundancy principles to ensure fault‑tolerant interactions.

- System requirements for interoperability, performance, scalability and security of ITS elements.

- Deployment scenarios & prioritization: short‑ and medium‑term use cases (e.g., digital mapping, dynamic navigation, corridor management, parking/valet, VRU support, platooning, intersection assistance, tolling).

- Digital twin requirements - ensuring real‑time alignment between physical infrastructure and its digital representation.

- Standardization pathway: identification of existing standards to reuse, gaps/overlaps, and needs for new standards per prioritized applications.

Applications

CEN/TR 17828 is practical for planning and deploying infrastructure that cooperates with automated vehicles. Typical applications include:

- Accurate digital mapping and dynamic navigation support for automated driving.

- Contextual corridor management and dedicated lanes for mixed traffic.

- Roadside support for vulnerable road user (VRU) safety and platoon management.

- Automated parking, tolling approaches and intersection crossing assistance.

- Integration of C‑ITS elements into public warning systems and energy distribution for automated fleets.

Who should use this standard

- Road equipment and ITS suppliers

- Road authorities, infrastructure managers and local governments

- Vehicle manufacturers and ADAS/automated driving system integrators

- Standards developers (CEN TC226 / WG12), policymakers and regulators

- Researchers and urban mobility planners

Related standards & next steps

Release 1 is a reference framework guiding WG12’s next pre‑standardization studies. It maps priority use cases to existing standards and flags gaps for new standard development. For adoption guidance or feedback, consult your national standards body or CEN/TC 226.

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

BSI Group

BSI (British Standards Institution) is the business standards company that helps organizations make excellence a habit.

TÜV Rheinland

TÜV Rheinland is a leading international provider of technical services.

TÜV SÜD

TÜV SÜD is a trusted partner of choice for safety, security and sustainability solutions.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

CEN/TR 17828:2022 is a technical report published by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN). Its full title is "Road infrastructure - Automated vehicle interactions - Reference Framework Release 1". This standard covers: This document provides the current road equipment suppliers’ visions and their associated short term and medium-term priority deployment scenarios. Potential functional/operational standardization issues enabling a safe interaction of road equipment/infrastructure with automated vehicles in a consistent and interoperable way are identified. This is paving the way for a deeper analysis of standardization actions which are necessary for the deployment of priority short-time applications and use cases. This deeper analysis will be done at the level of each priority application/use case by identifying existing standards to be used, standards gaps/overlaps and new standards to be developed to support this deployment. The release 1 is focusing on short-term (2022 to 2027) and medium-term deployment. Further releases will update this initial vision according to short term deployment reality. The objectives of this document are to: - Support the TC 226 and its WG12 work through the development of a common vision of the roles and responsibilities of a modern, smart road infrastructure in the context of the automated vehicle deployment from SAE level 1 to SAE level 5. The roles and responsibilities of the road infrastructure are related to its level of intelligence provided by functions and data being managed at its level. - Promote the road equipment suppliers and partners visions associated to their short-term and medium- term priorities to European SDOs and European Union with the goal of having available relevant, consistent standards sets enabling the identified priority deployment scenarios. NOTE Road equipment/infrastructure includes the physical reality as its digital representation (digital twin). Both need to present a real time consistency.

This document provides the current road equipment suppliers’ visions and their associated short term and medium-term priority deployment scenarios. Potential functional/operational standardization issues enabling a safe interaction of road equipment/infrastructure with automated vehicles in a consistent and interoperable way are identified. This is paving the way for a deeper analysis of standardization actions which are necessary for the deployment of priority short-time applications and use cases. This deeper analysis will be done at the level of each priority application/use case by identifying existing standards to be used, standards gaps/overlaps and new standards to be developed to support this deployment. The release 1 is focusing on short-term (2022 to 2027) and medium-term deployment. Further releases will update this initial vision according to short term deployment reality. The objectives of this document are to: - Support the TC 226 and its WG12 work through the development of a common vision of the roles and responsibilities of a modern, smart road infrastructure in the context of the automated vehicle deployment from SAE level 1 to SAE level 5. The roles and responsibilities of the road infrastructure are related to its level of intelligence provided by functions and data being managed at its level. - Promote the road equipment suppliers and partners visions associated to their short-term and medium- term priorities to European SDOs and European Union with the goal of having available relevant, consistent standards sets enabling the identified priority deployment scenarios. NOTE Road equipment/infrastructure includes the physical reality as its digital representation (digital twin). Both need to present a real time consistency.

CEN/TR 17828:2022 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 35.240.60 - IT applications in transport; 43.020 - Road vehicles in general; 93.080.99 - Other standards related to road engineering. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

CEN/TR 17828:2022 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-september-2022

Cestna infrastruktura - Avtomatizirane interakcije vozil - Referenčni okvir, različica

Road infrastructure - Automated vehicle interactions - Reference Framework Release 1

Straßeninfrastruktur - Bezugsrahmen für die Interaktion automatisierter Fahrzeuge

Interactions Infrastructure routière - Véhicule automatisé : Cadre de référence Version 1

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: CEN/TR 17828:2022

ICS:

35.240.60 Uporabniške rešitve IT v IT applications in transport

prometu

43.020 Cestna vozila na splošno Road vehicles in general

93.080.99 Drugi standardi v zvezi s Other standards related to

cestnim inženiringom road engineering

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

CEN/TR 17828

TECHNICAL REPORT

RAPPORT TECHNIQUE

June 2022

TECHNISCHER BERICHT

ICS 35.240.60; 43.020; 93.080.99

English Version

Road infrastructure - Automated vehicle interactions -

Reference Framework Release 1

Interactions Infrastructures routières - Véhicules Straßeninfrastruktur - Bezugsrahmen für die

automatisés - Cadre de référence Interaktion automatisierter Fahrzeuge

This Technical Report was approved by CEN on 6 June 2022. It has been drawn up by the Technical Committee CEN/TC 226.

CEN members are the national standards bodies of Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia,

Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway,

Poland, Portugal, Republic of North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and

United Kingdom.

EUROPEAN COMMITTEE FOR STANDARDIZATION

COMITÉ EUROPÉEN DE NORMALISATION

EUROPÄISCHES KOMITEE FÜR NORMUNG

CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Rue de la Science 23, B-1040 Brussels

© 2022 CEN All rights of exploitation in any form and by any means reserved Ref. No. CEN/TR 17828:2022 E

worldwide for CEN national Members.

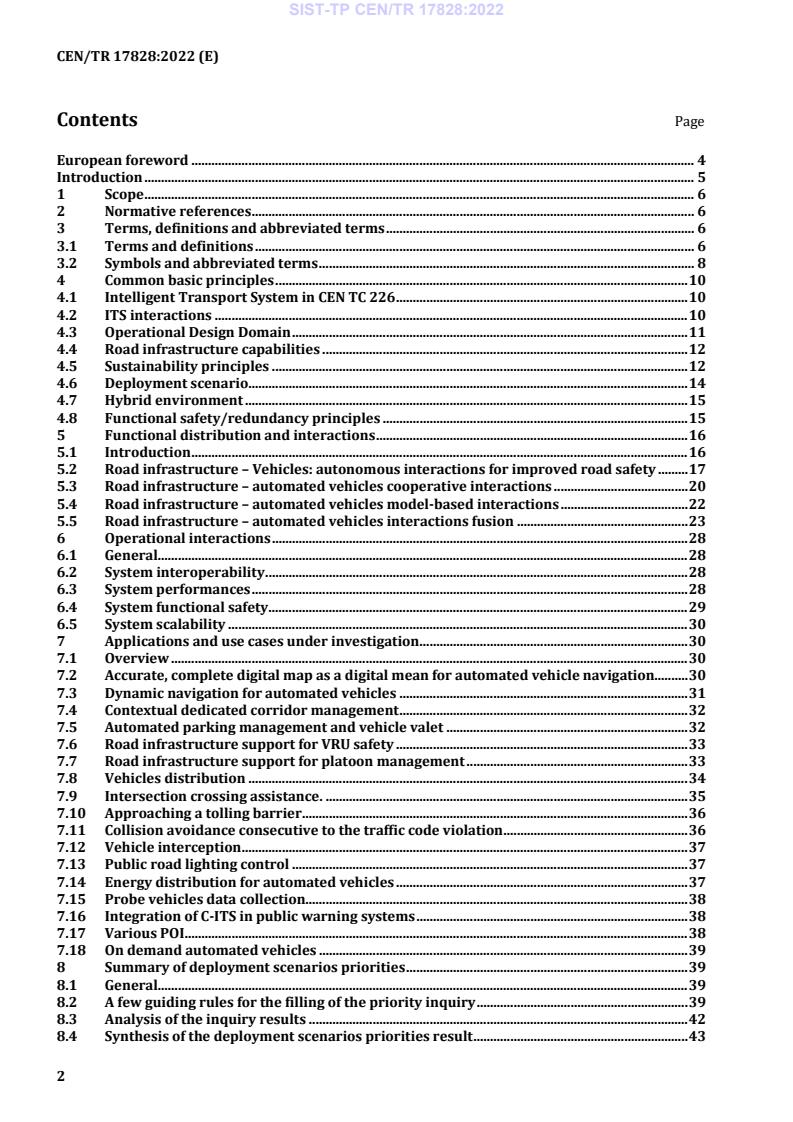

Contents Page

European foreword . 4

Introduction . 5

1 Scope . 6

2 Normative references . 6

3 Terms, definitions and abbreviated terms . 6

3.1 Terms and definitions . 6

3.2 Symbols and abbreviated terms . 8

4 Common basic principles . 10

4.1 Intelligent Transport System in CEN TC 226 . 10

4.2 ITS interactions . 10

4.3 Operational Design Domain . 11

4.4 Road infrastructure capabilities . 12

4.5 Sustainability principles . 12

4.6 Deployment scenario . 14

4.7 Hybrid environment . 15

4.8 Functional safety/redundancy principles . 15

5 Functional distribution and interactions . 16

5.1 Introduction . 16

5.2 Road infrastructure – Vehicles: autonomous interactions for improved road safety . 17

5.3 Road infrastructure – automated vehicles cooperative interactions . 20

5.4 Road infrastructure – automated vehicles model-based interactions . 22

5.5 Road infrastructure – automated vehicles interactions fusion . 23

6 Operational interactions . 28

6.1 General. 28

6.2 System interoperability . 28

6.3 System performances . 28

6.4 System functional safety . 29

6.5 System scalability . 30

7 Applications and use cases under investigation. . 30

7.1 Overview . 30

7.2 Accurate, complete digital map as a digital mean for automated vehicle navigation. 30

7.3 Dynamic navigation for automated vehicles . 31

7.4 Contextual dedicated corridor management . 32

7.5 Automated parking management and vehicle valet . 32

7.6 Road infrastructure support for VRU safety . 33

7.7 Road infrastructure support for platoon management . 33

7.8 Vehicles distribution . 34

7.9 Intersection crossing assistance. . 35

7.10 Approaching a tolling barrier . 36

7.11 Collision avoidance consecutive to the traffic code violation . 36

7.12 Vehicle interception . 37

7.13 Public road lighting control . 37

7.14 Energy distribution for automated vehicles . 37

7.15 Probe vehicles data collection. 38

7.16 Integration of C-ITS in public warning systems . 38

7.17 Various POI. 38

7.18 On demand automated vehicles . 39

8 Summary of deployment scenarios priorities . 39

8.1 General. 39

8.2 A few guiding rules for the filling of the priority inquiry . 39

8.3 Analysis of the inquiry results . 42

8.4 Synthesis of the deployment scenarios priorities result . 43

9 Long-term evolution . 45

10 Economic & organizational potential impacts . 46

10.1 General . 46

10.2 Roles and responsibilities . 46

10.3 Organizational impacts . 46

10.4 Economic impacts . 49

11 Projected standardization approaches for identified priority applications. 50

11.1 General . 50

11.2 Contextual, dedicated corridor management . 50

11.3 Road infrastructure support for VRUs safety . 50

11.4 Parking management . 51

11.5 Vehicles’ distribution . 51

11.6 Approaching a tolling barrier . 51

11.7 Accurate digital map . 52

11.8 Dynamic navigation . 52

11.9 Intersection crossing assist. 52

11.10 Platooning . 53

Bibliography . 54

European foreword

This document (CEN/TR 17828:2022) has been prepared by Technical Committee CEN/TC 226 “Road

equipment”, the secretariat of which is held by AFNOR.

This document provides a pre-standardization study for the road infrastructure – automated vehicle

interactions which will be used by WG12 as a reference framework for the development of other pre-

standardization studies.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. CEN shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

Any feedback and questions on this document should be directed to the users’ national standards body.

A complete listing of these bodies can be found on the CEN website.

Introduction

A shared general vision between the main stakeholders which are involved in the development and

deployment of automated vehicles is that their complexity requires a constant effort to converge toward

safe, interoperable solutions.

This complexity is related to the considered mobility environment, in terms of road topography, traffic

and weather conditions, human behaviour, vehicle diversity, etc.

This led these main stakeholders to think that it is necessary, in a certain number of situations, to provide

some forms of cooperation between the roadside infrastructure (road equipment) and automated

vehicles.

Such necessity is reinforced through the fact that the deployment of automated vehicles will be

progressive, leading to a heterogeneous mix of different levels of automated vehicles from not automated

in-service vehicles (SAE level 0) to fully automated vehicles (SAE levels 4 &5).

This cooperation will require different forms of interactions between the road equipment and the

embedded ADAS of automated vehicles. These interactions should be reliable and secure in such a way to

be fault tolerant during the fulfilment of the main functions of the automated vehicle. This latest

constraint means that system redundancy will be a key element ensuring the required functional safety

of the system.

1 Scope

This document provides the current road equipment suppliers’ visions and their associated short term

and medium-term priority deployment scenarios. Potential functional/operational standardization

issues enabling a safe interaction of road equipment/infrastructure with automated vehicles in a

consistent and interoperable way are identified. This is paving the way for a deeper analysis of

standardization actions which are necessary for the deployment of priority short-time applications and

use cases.

This deeper analysis will be done at the level of each priority application/use case by identifying existing

standards to be used, standards gaps/overlaps and new standards to be developed to support this

deployment.

The release 1 is focusing on short-term (2022 to 2027) and medium-term deployment. Further releases

will update this initial vision according to short term deployment reality.

The objectives of this document are to:

— Support the TC 226 and its WG12 work through the development of a common vision of the roles and

responsibilities of a modern, smart road infrastructure in the context of the automated vehicle

deployment from SAE level 1 to SAE level 5. The roles and responsibilities of the road infrastructure

are related to its level of intelligence provided by functions and data being managed at its level.

— Promote the road equipment suppliers’ and partners’ visions associated to their short-term and

medium- term priorities to European SDOs and the European Union with the goal of having available

relevant, consistent standards sets enabling the identified priority deployment scenarios.

NOTE Road equipment/infrastructure includes the physical reality as its digital representation (digital twin).

Both need to present a real time consistency.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references in this document.

3 Terms, definitions and abbreviated terms

For the purposes of this document, the following terms, definitions and abbreviated terms apply.

3.1 Terms and definitions

3.1.1

use case

specific situation describing stakeholders’ interactions which illustrate the execution of one or several

customers’ service(s) via support applications

Note 1 to entry: The stakeholders’ interactions are represented via standardized exchanges between elements

constituting the Intelligent Transport System (ITS).

3.1.2

user

equipped or un-equipped road user such as drivers, vulnerable road users and suppliers which are

themselves accessing services provided by a private or public organization

3.1.3

personal ITS-S

ITS-S in a nomadic ITS sub-system in the context of a portable device

3.1.4

traffic scenario

possible behavioural of a use case situation in the form of a sequence of events that affect the mobility

and safety with respect to the initial situation

Note 1 to entry: Scenario is defined in terms of the positioning of a User and other road users, environmental

situations, the system equipment, and any obstacles and environmental conditions hampering the detectability of

the User, the behavioural relations and communication performance of the ITS system. Therefore, the sequence of

events includes road user activities, movement of obstacles, and changes in the conditions that affect the VRU safety

with respect to the initial situation.

3.1.5

deployment scenarios

main steps to be followed to deploy and manage a functionally and operationally specified system during

its whole life cycle, starting with the system installation and commissioning and finishing with its

recycling

Note 1 to entry: If the system is a new one, its compatibility with existing legacy systems needs to be considered.

3.1.6

manoeuvres

specific and recognized movements bringing an actor, e.g. vulnerable road user, vehicle or any other form

of transport, from one position to another with a given velocity (dynamic)

3.1.7

traffic conflict

situation involving two or more moving users or vehicles approaching each other in such a way that a

traffic collision would ensue unless at least one of the users or vehicles performs an emergency

manoeuvre

Note 1 to entry: Traffic conflicts are defined by the following parameters:

— traffic conflict point (time and space) where the trajectories intersect,

— time-to-collision, distance-to-collision, post-encroachment time, and angle of conflict.

3.1.8

road

way allowing the passage of vehicles, people and/or animals that is made of none, one or a combination

of the following lanes: driving lane, bicycle lane and sidewalk

3.1.9

vehicle

road vehicle designed to legally carry people or cargo on public roads and highways such as busses, cars,

trucks, vans, motor homes, and motorcycles

Note 1 to entry: This does not include motor driven vehicles not approved for use of the road, such as forklifts or

marine vehicles.

3.1.10

vru

non-motorized road users as well as L class of vehicles

Note 1 to entry: L class of vehicles are defined in Annex I of EU Regulation 168/2013.

3.1.11

vru-s

ensemble of ITS stations interacting with each other to support VRU user cases, e.g. personal ITS-S, vehicle

ITS-S, roadside ITS-S or Central ITS-S

3.2 Symbols and abbreviated terms

ACC Adaptive Cruise Control

ADAS Advanced Driving Assistance System

AEBS Advanced Emergency Braking System

CACC Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control

CAM Cooperative Awareness Message

CCAM Cooperative, Connected Automated Mobility

CDA Cooperative Driving Automation

CEDR Conférence Européenne des Directeurs de Routes

CPM Collaborative Perception Message

CPS Collaborative Perception Service

C-ITS Cooperative ITS

CMC Connected Motorcycle Consortium

C2C-CC Car to Car Communication Consortium

DENM Decentralized Environmental Notification Message

DDT Dynamic Driving Task

FMECA Failure Mode Effects and Criticality Analysis

GLOSA Green Light Optimal Speed Advisory

GNSS Global Navigation Satellite System

ISAD Infrastructure Support levels for Automated Driving

ITS Intelligent Transport System

ITS-S ITS Station

IVI In Vehicle Information

IVIM Infrastructure to Vehicle Information Message

LDM Local Dynamic Map

LTCA Long Term Certificate Administration

MANTRA Making full use of Automation for National Road Transport Authorities

MAP Map

MCO: Multi Channel Operation

MCM Manoeuvre Coordination Message

MCS Manoeuvre Coordination Service

ODD Operational Design Domain

PAC V2X Perception Augmented by Cooperation V2X

PCA Pseudonyms Certificates Administration

POI Point Of Interest

POTI Position and Time management

ROI Return On Investment

RSU Roadside Unit

RTCM Radio Technical Commission for Maritime services

RTCMEM RTCM Extended Message

RTK Real Time Kinematic

SAE Society of Automotive Engineers

SDO Standards Development Organization

SPaT Signal Phase and Timing

STF: Specialist Task Force

TCU Telematic Control Unit

TTC Time-To-Collision

TVRA Threat Vulnerability Risk Analysis

V2I Vehicle to Infrastructure

V2V Vehicle to Vehicle

V2X Vehicle to X

VAM VRU Awareness Message

VBS VRU Awareness Basic Service

VITS-S Vehicle ITS Station

VRU Vulnerable Road Users

VRU-S Vulnerable Road User System

4 Common basic principles

4.1 Intelligent Transport System in CEN TC 226

According to the European Commission ITS Directive (2010/40/EU), Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS)

are advanced applications which without embodying intelligence as such aim to provide innovative

services relating to different modes of transport and traffic management and enable various users to be

better informed and make safer, more coordinated and "smarter" use of transport networks.

ITS integrate telecommunications, electronics and information technologies with transport engineering

in order to plan, operate, maintain and manage transport systems.

The TC 226 WG12 is focusing on the road interaction- ADAS / Automated vehicles, meaning that the

considered ITS is composed of at least two elements: The road infrastructure and the automated vehicle

(including its ADAS) which are interacting together.

The inclusion of automated vehicle in ITS leads automatically to the design and development of innovative

services as such system elements are not yet deployed. The automated vehicle standardization is already

considered in CEN TC 278, ETSI TC ITS and ISO TC 204 which are all focusing on ITS.

It is then the object of this WG12 to work on the identification of these innovative services, their selection

and the associated standardization needs in strong liaisons with the on-going ITS standardization work.

4.2 ITS interactions

An ITS may exhibit several types of interactions which are relevant to all TC 226 WGs. These types of

interactions are relative of the functional distribution of the information technologies, data and

communication means:

The road may be passive, not embodying some information technology. Examples are the horizontal

marking or the vertical signs. However, even such a passive road is designed with a lot of human

intelligence. In this case, the interactions with automated vehicles' embedded ADAS are mainly achieved

by the vehicle itself using some relevant sensors (ADAS: for example, cameras, radars, lidars). In this case,

advanced applications will analyse the collected perception data of the vehicle for automatically, safely

guiding it.

Mobile objects (e.g. vehicles, Vulnerable Road Users (VRUs), obstacles, etc.) can also be passively

perceived by vehicle sensors and then processed by advanced applications for collision avoidance

purposes.

The road infrastructure and mobile objects may be equipped with electronic devices, information

processing and telecommunication technologies enabling them to interact and cooperate via standard

communication protocols and information exchanges (standard message sets).

Several interaction capabilities are existing at the level of automated vehicles (see Figure 1). These

capabilities are constituting a de-facto redundancy system which can be used to detect an ITS failure or a

cyberattack and then automatically reconfigure the system to maintain its operationality. However, this

advantage requires constantly verifying the consistency of existing interactions results which are

providing several sources of information (e.g. the consistency between the horizontal marking / vertical

signing and the digital twin, or the consistency between the vehicle autonomous perception and received

remote perception via C-ITS).

Direct interactions between the road infrastructure and the automated vehicles are made using actuators

and sensors which need to respect minimum quality requirements according to the vehicles ADASs which

are using the collected data. These autonomous interactions can be disturbed consecutively to their

quality degradation, visibility problems (obstacles or bad weather conditions) or absence.

Cooperative ITS (C-ITS) and more generally vehicles’ connectivity is achieved via radio

telecommunication (local ad-hoc networks (short range) or global networks (long range)) which of

course may be not always available.

A local dynamic map should be accurate enough and complete, reflecting the horizontal marking and

vertical signing. The vehicles’ map matching is also requiring an accurate vehicle positioning system

which is not yet available. A positioning system or the associated digital map should be fault tolerant,

resilient in case of temporary perception problems.

Figure 1 — Three categories of interactions between the automated vehicles and its

environment

The consistency of the WG12 approach shall be maintained between Task Groups (TGs) cooperation:

— TG1 needs to consider the perception data fusion between locally collected perception data, remote

perception data received from the ITS connectivity and digital data provided by the embedded vehicle

Local Dynamic Map (LDM).

— TG4 also needs to maintain the consistency between the Local Digital Map data and the perception

data received from local vehicle’s sensors.

4.3 Operational Design Domain

Operational Design Domain (ODD) is a description of the specific operating conditions in which the

automated driving system is designed to properly operate, including but not limited to roadway types,

speed range, environmental conditions (weather, daytime / night-time, etc.), prevailing traffic law and

regulations, and other domain constraints [41]. An ODD can be very limited: for instance, a single fixed

route on low-speed public streets or private grounds (such as business parks) in temperate weather

conditions during daylight hours (Waymo 2017).

The ODD is relevant to all level of automation except for 0 (not applicable) and 5 (unlimited). Any

automation use case of level 1 to 4 is usable only in its specific ODD.

4.4 Road infrastructure capabilities

The deployment of automated vehicles needs some evolution of the road infrastructure capabilities, as

currently, in-service road infrastructure and equipment are designed only for human driven vehicles.

However, such evolution must respect the long-term cohabitation of automated vehicles with human

driven vehicles (hybrid environment being discussed here below).

An automated vehicle needs to know if the road infrastructure offers the expected capabilities to stay in

automated mode. If it is not the case, SAE level 1 to 3 vehicles may transfer their driving control to the

human driver who is still available in the vehicle. However, this transfer decision needs to respect some

transition rules ensuring that the driver is ready to take back control of the vehicle. Driving mode transfer

is then requiring an anticipation (prediction) of the loss of the road infrastructure capability to support

automated vehicles motions.

SAE level 4 and 5 vehicles may not have a human driver inside, however, in such cases they need to be

remotely supervised with the objective to be remotely controlled (at least partly) if the road

infrastructure no longer offers the expected capabilities.

The Inframix European project proposed an infrastructure categorization model, represented in Figure 2

(ISAD: Infrastructure Support levels for Automated Driving) [33].

Figure 2 — ISAD levels

4.5 Sustainability principles

The life cycles of vehicles and road infrastructures are covering different long periods of time from their

engineering phase to their recycling phase (see Figure 3). These periods of time may be different for the

two main system elements (road infrastructure and vehicles).

Interactions between the road infrastructure and the automated vehicles need standard exchange

protocols which are not independent of technologies being used. Moreover, preventive, corrective and

evolutive maintenance operations need to manage them consistently.

One important operational requirement is the interoperability between interacting road infrastructure

elements and automated vehicles elements. This interoperability needs to be maintained during the life

cycle of both the road infrastructure and automated vehicles.

This interoperability necessity imposes a specific change management process enabling the secured

cohabitation, during determined periods of time, of several versions of standard information exchange

protocols without cross disturbances of operational ITS. Different versions need to cohabit together

without operational problems.

Such specific change management processes need to be applied in strong concertation between the

vehicles’ manufacturers and the road operators/managers who have the responsibility to develop

together some migration plan including a common and consistent selection of changes to be considered

as well as its deployment operation.

Figure 3 — ITS life cycle

The interoperability requirement needs a continuous cooperation between the main stakeholders of the

ITS. This is true at:

— The engineering level for the system and system elements specification. When standards are

required, the standards need to be developed/selected in such a way as to enable a full

interoperability of the constituted system. Generally, the required standards are regrouped into

“profiles” (e.g. “communication profiles”, “security profiles”, “applications profiles” are constituting

what can be called “exchange profiles”).

— The engineering level for the system validation including system elements testing, system integration

and system validation in diverse environments. Then resulting products can be delivered on the

market after a certification/compliance assessment validating their functionality, interoperability

and safe operation in targeted environments.

— During the system operation when new versions of the system need to be delivered. In such cases, a

change management process is enabling the ITS stakeholders to agree on interoperable evolutions

constituting the new version. Some migration plans have then to be proposed to avoid maintaining

too many different versions simultaneously.

— The hardware component recycling needs to be considered during their engineering phase.

4.6 Deployment scenario

A deployment scenario is a set of activities (steps of the scenario) which lead to the market delivery of

new customer services supported by applications and targeting identified use cases (situations of usage).

The following activities can be considered as being the main ones belonging to the identified deployment

scenarios involving automated vehicles and a supporting smart road infrastructure:

— Development / stabilization of a relevant set of standards per identified deployment scenario. These

standards are judged necessary for the interoperability of automated vehicles and the road

infrastructure during their identified interactions whatever the type of interactions.

— Development and stabilization of the test standards which are judged necessary for the standards

compliance assessment of developed products which are proposed to be delivered on the market.

— Achievement of the validation/certification procedures which are made mandatory to achieve the

compliance assessment and the quality verification of proposed products and subsystems.

— Possibly some pre-deployment projects completing the validation/certification process with the

objective to verify the good operation of a set of certified products constituting an ITS.

For short-term deployment scenarios, it is considered that this set of activities can be achieved by the

vehicles and the road equipment industries within a 5-year period (2 years for the development of

standards (basic and tests) and 3 years for the pre-deployment projects).

For medium-term deployment scenarios, it is considered that also 5 years are necessary, but starting at

the start of the short-term deployment, that is to say within 10 years.

NOTE A deployment scenario can be resulting from research or Proof of Concept (POC) project(s) which might

be proposing new standards or evolutions of existing standards.

Consequently, a deployment scenario can be applied to a new identified customer service which is

supported by a given application used in well identified situations (use cases). Such approach is

illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4 — Illustration of relationships existing between a new customer service and its

deployment.

Customer service definition -> supporting application-> main use cases -> deployment scenario including

a standardization activity.

4.7 Hybrid environment

The deployment of the automated vehicles from SAE level 1 to 5 will take a long time (at least 20 to 30

years). Consequently, the road infrastructure will have to interact with a diversity of vehicles from non-

connected/cooperative in-service vehicles to fully connected/cooperative vehicles of several deployed

versions. The first version of cooperative vehicles, which deployment is starting is called release 1, but

other releases are under specification and validation (release 1.5, release 2 in ETSI and CEN / ISO focusing

more on automated vehicles).

For a long time, connected/cooperating vehicles will only be partly automated (level 1 to 3) with some of

them (e.g. shuttles, taxis) running in protected environments (level 4). This is leading to the cohabitation

on the same road infrastructure of human driven vehicles and automated vehicles which may have to

transit to a human driving mode if the road infrastructure doesn’t have the capability to support them.

Such a hybrid environment is creating problems to the automated vehicle as human driven vehicles

behaviours are not predictable as often, they don’t respect the traffic code, while automated vehicles must

respect it.

One interesting characteristic of automated vehicles is this respect of the traffic code as this may have a

quick impact on all vehicles which can be de facto constrained to act similarly when following automated

vehicles.

Automated vehicles are cooperating (V2V) and are cooperating with the road infrastructure (V2I) so

acting to increase road safety and traffic efficiency. Consequently, if more cooperative vehicles are present

in traffic, it is possible to better control the traffic in terms of safety and efficiency.

4.8 Functional safety/redundancy principles

Automated vehicles are robots which are executing program instructions respecting the road traffic code

and other rules which must avoid severe accidents causing human fatalities or injuries. For this purpose,

automated vehicles need to constantly have a complete perception of their environment via the identified

interactions previously mentioned in 4.2. Then, the whole operational ITS needs to remain functional,

satisfying its minimum performances requirement. This is called functional safety and includes the

management of the following situations:

Failure of hardware/software components at the ITS level (not only in the automated vehicle itself but

also in other elements of the system including the road infrastructure in case of cooperation). In the

vehicle industry, the FMECA (Failure Mode Effect and Criticality Analysis) methodology is used to analyse

the functional safety risks and their likelihood with the objective to mitigate them (fault tolerance) in such

a way to avoid severe accidents. It has to be noted that the software is occupying more and more place

and that new release mixed with the complexity of situations can generate more and more bugs, so more

risk of failure.

Cyberattacks which may also cause some dysfunctions at the ITS level. Cyberattacks may exploit open

interfaces such as telecommunication functions. ETSI TC ITS WG5 has been conducting a TVRA (Threat

Vulnerability Risk Analysis) focusing on ITS G5 technology for proposing a standard security profile

mitigating the risks of cyberattacks. But the automated vehicle was not at that time in the scope of the

study.

Many reports are existing about functional safety and in particular with regard to cybersecurity. The three

following reports are good references:

— Safer Roads with Automated Vehicles [35],

— Good practices for security in Smart cars [36],

— Cybersecurity Challenges in Uptake of Artificial Intelligence in Autonomous Driving [37].

Moreover, two important ISO standards are covering this aspect of functional safety:

ISO 26262 [43] and particularly its Part 3 HARA deals with different aspects of the functional safety in

Automotive. It is designed to eliminate any unacceptable risk to the human life. The purpose of HARA is

to identify the malfunctions that could possibly lead to E/E system hazard and assess the risk associated

to them.

SOTIF (ISO/PAS 21448 [44]) provides guidance on design, verification, and validation measures. Applying

these measures helps you achieve safety in situations without failure.

Examples that ISO 21448 provides:

— Design measure example: requirement for sensor performance,

— Verification measure example: Test cases with high coverage of scenarios,

— Validation measure example: Simulations.

One solution which can be used to overcome some failures / fault is the creation of redundancies at the

level of the ITS. This could be achieved by exploiting the various capabilities of the ITS elements including

the road infrastructure.

As it is shown at the level of ITS interactions, the automated vehicles may have redundant functions which

can at least temporarily overcome the failure of one of them. For example:

A failure of the autonomous perception of the vehicle can be overcome by the local dynamic map or the

remote perception provided by other ITS-S via the C-ITS network.

A failure of C-ITS can be overcome by the local perception of the vehicle.

C-ITS based on local ad-hoc area networks is also offering redundant communication capabilities (several

available channels, see several ad-hoc network technologies (ITS G5, C-V2X). However, standard channels

management should be provided to maintain the ITS-S interoperability. In ETSI, the STF 585 supported

by the European Commission has this objective to develop MCO (Multi-Channel Operation) standards

considering the two available ad-hoc network technologies and their usage for the support of available

services. Moreover, the progressive development of the 5G is also adding a new telecommunication

redundancy. But as 5G is only an access network, generally, it will be necessary to consider the whole

global network (e.g. Internet or local area fibre network) to be used for assessing their performances.

Another solution is the monitoring of the automated vehicles behaviour and performances with the

objective to detect some deviations compared to reference models. This could lead to preventive

maintenance. Such approach is mandatory for automated vehicles level 4 and 5 which need to be

supervised.

5 Functional distribution and interactions

5.1 Introduction

An Intelligent Transport System (ITS) can be composed of several elements which are interacting

together to achieve several objectives. Each system element comprises a set of functions and data which

contribute to the common goals. These functions and data can be distributed (see an example of

distribution in Figure 5) according to different technical, economic, and organizational criteria related to

the respective visions of the main involved stakeholders. A selected functional / data distribution leads

to system elements interactions which need to be identified and specified.

Figure 5 — Example of ITS functional / data distribution

In 5.2, three categories of interactions have been identified which can be existing between the main

elements of an intelligent transport system. These interactions are more detailed in Clause 6:

— 6.2 focuses on direct interactions between the road infrastructure and automated vehicles via their

respective sensors and actioners.

— 6.3 considers cooperative interactions between the road infrastructure and automated vehicles.

— 6.4 considers model-based interactions between a digital representation of the road infrastructure

and ITS evolving dynamic objects and automated vehicles.

The functional / data distribution schema which is retained is immediately impacting the roles and

responsibilities of involved stakeholders.

As identified in 5.2, these three categories of interactions are de-facto constituting a redundant system

which can be used to increase the functional safety of the ITS via the detection of inconsistencies and

automatic reconfiguration.

Interactions between ITS elements which integrate redundant functions enable the fusion of resulting

data. This fusion may then augment the obtained result (e.g. an augmented perception) or may enable the

detection of inconsistency (e.g. the detection a failure or of a cyberattack).

5.2 Road infrastructure – Vehicles: autonomous interactions for improved road safety

rd

The EU 3 Mobility Package (2018) pursues a drastic reduction in accidents, road fatalities and injuries,

by combining the General Safety Regulation (GSR) with the Road Infrastructure Management Directive

(RISM).

CEN/TR 17828:2

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...