ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014

(Main)Safety aspects — Guidelines for child safety in standards and other specifications

Safety aspects — Guidelines for child safety in standards and other specifications

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 provides guidance to experts who develop and revise standards, specifications and similar publications. It aims to address potential sources of bodily harm to children from products that they use, or with which they are likely to come into contact, even if not specifically intended for children. ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 does not provide guidance on the prevention of intentional harm (e.g. child abuse) or non-physical forms of harm, such as psychological harm (e.g. intimidation). ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 does not address the economic consequences of the above.

Aspects liés à la sécurité — Principes directeurs pour la sécurité des enfants dans les normes et autres spécifications

L'ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 fournit des lignes directrices aux experts concernés par l'élaboration et la révision de normes, de spécifications et de publications similaires. Il vise à traiter des sources potentielles de dommages corporels pour les enfants, présentes dans les produits qu'ils utilisent ou avec lesquels ils sont susceptibles d'entrer en contact, même s'ils ne sont pas spécifiquement destinés à des enfants. L'ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 ne fournit pas de lignes directrices concernant la prévention des dommages intentionnels (par exemple, violence faite aux enfants) ou de formes non physiques de dommages, telles que les dommages psychologiques (par exemple, intimidation). L'ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 ne traite pas des conséquences économiques de ce qui précède.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 07-Dec-2014

- Technical Committee

- ISO/COPOLCO - Committee on consumer policy

- Drafting Committee

- ISO/COPOLCO - Committee on consumer policy

- Current Stage

- 9093 - International Standard confirmed

- Start Date

- 22-Sep-2023

- Completion Date

- 12-Feb-2026

Relations

- Effective Date

- 11-May-2013

Overview

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 - Safety aspects - Guidelines for child safety in standards and other specifications provides guidance for experts who develop or revise standards, specifications and similar publications. The Guide helps identify and address potential sources of bodily harm to children from products, packaging, built environments, services and processes they use or are likely to encounter - even if those items are not specifically intended for children. It does not cover prevention of intentional harm (e.g., abuse), non‑physical harms (e.g., psychological harm), or economic consequences.

Key topics and technical focus

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 organizes practical guidance around child‑relevant safety considerations rather than prescriptive test methods. Core topics include:

- Child definition and age descriptors (the Guide defines “child” as under 14 years while noting local variations).

- General approach and risk assessment: systematic assessment of hazards and reasonably foreseeable use.

- Child development, behaviour and vulnerability: anthropometry, motor, physiological and cognitive development; how developmental age differs from chronological age.

- Safe environments: physical, social and sleep environments that influence child safety.

- Hazard taxonomy: structured treatment of hazards relevant to children, including mechanical and fall hazards, drowning, suffocation, strangulation, small-object and suction hazards, fire and explosion, thermal, chemical, electrical, radiation, noise and biological hazards.

- Adequacy of safeguards: considerations for product, installation, personal, behavioural and instructional safeguards.

- Supporting materials: Annex A (assessment checklist) and Annex B (information on injury databases) to assist standards developers and safety assessors.

Practical applications and users

Who benefits from using this Guide:

- Standards developers and technical committees - integrate child‑centred safety guidance into product, packaging and environment standards.

- Designers and manufacturers - apply child‑safety principles during design, materials selection and packaging decisions.

- Regulators, policy makers and safety inspectors - use the Guide as background when specific standards are absent.

- Architects, service providers and educators - evaluate environments and services (including sleep spaces) for child risk.

- Auditors and product‑safety professionals - use Annex A checklist and hazard lists for conformity assessment and risk mitigation.

Practical uses include hazard identification, drafting age‑appropriate safety requirements, informing instructions and warnings, and assessing adequacy of engineered and behavioral safeguards.

Related standards and resources

- ISO/IEC Guide 51 - general principles for risk assessment and risk reduction; Guide 50 complements Guide 51 by focusing on child‑specific considerations.

- WHO/UNICEF reports on child injury prevention are useful context for prevalence and public‑health priorities.

Keywords: ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014, child safety in standards, hazard assessment, product safety, risk assessment, child development, safeguards, standards developers.

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 - Safety aspects -- Guidelines for child safety in standards and other specifications

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 - Aspects liés a la sécurité -- Principes directeurs pour la sécurité des enfants dans les normes et autres spécifications

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 is a guide published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Safety aspects — Guidelines for child safety in standards and other specifications". This standard covers: ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 provides guidance to experts who develop and revise standards, specifications and similar publications. It aims to address potential sources of bodily harm to children from products that they use, or with which they are likely to come into contact, even if not specifically intended for children. ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 does not provide guidance on the prevention of intentional harm (e.g. child abuse) or non-physical forms of harm, such as psychological harm (e.g. intimidation). ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 does not address the economic consequences of the above.

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 provides guidance to experts who develop and revise standards, specifications and similar publications. It aims to address potential sources of bodily harm to children from products that they use, or with which they are likely to come into contact, even if not specifically intended for children. ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 does not provide guidance on the prevention of intentional harm (e.g. child abuse) or non-physical forms of harm, such as psychological harm (e.g. intimidation). ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 does not address the economic consequences of the above.

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 01.120 - Standardization. General rules; 97.190 - Equipment for children. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to ISO/IEC Guide 50:2002. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

ISO/IEC Guide 50:2014 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

GUIDE 50

Third edition

2014-12-15

Safety aspects — Guidelines for

child safety in standards and other

specifications

Aspects liés à la sécurité — Principes directeurs pour la sécurité des

enfants dans les normes et autres spécifications

Reference number

©

ISO/IEC 2014

© ISO/IEC 2014

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior

written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of

the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

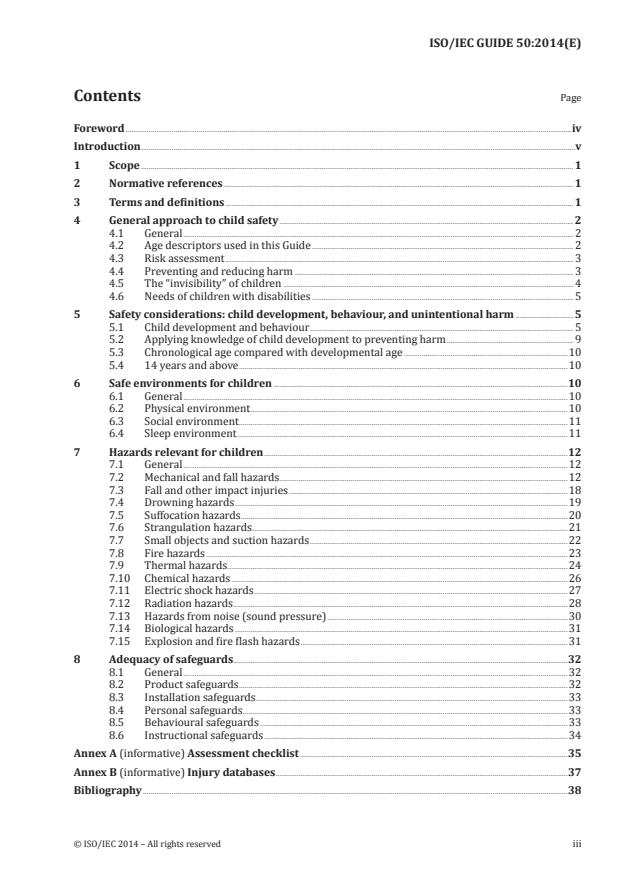

Contents Page

Foreword .iv

Introduction .v

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 General approach to child safety . 2

4.1 General . 2

4.2 Age descriptors used in this Guide . 2

4.3 Risk assessment . 3

4.4 Preventing and reducing harm . 3

4.5 The “invisibility” of children . 4

4.6 Needs of children with disabilities . 5

5 Safety considerations: child development, behaviour, and unintentional harm .5

5.1 Child development and behaviour . 5

5.2 Applying knowledge of child development to preventing harm . 9

5.3 Chronological age compared with developmental age .10

5.4 14 years and above .10

6 Safe environments for children .10

6.1 General .10

6.2 Physical environment .10

6.3 Social environment .11

6.4 Sleep environment .11

7 Hazards relevant for children .12

7.1 General .12

7.2 Mechanical and fall hazards.12

7.3 Fall and other impact injuries .18

7.4 Drowning hazards .19

7.5 Suffocation hazards .20

7.6 Strangulation hazards .21

7.7 Small objects and suction hazards .22

7.8 Fire hazards .23

7.9 Thermal hazards .24

7.10 Chemical hazards .26

7.11 Electric shock hazards .27

7.12 Radiation hazards .28

7.13 Hazards from noise (sound pressure) .30

7.14 Biological hazards .31

7.15 Explosion and fire flash hazards .31

8 Adequacy of safeguards .32

8.1 General .32

8.2 Product safeguards .32

8.3 Installation safeguards .33

8.4 Personal safeguards .33

8.5 Behavioural safeguards .33

8.6 Instructional safeguards .34

Annex A (informative) Assessment checklist .35

Annex B (informative) Injury databases .37

Bibliography .38

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved iii

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) and IEC (the International Electrotechnical

Commission) are worldwide federations of national standards bodies (ISO member bodies and IEC

national committees). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through

ISO and IEC technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO or IEC, also take part in the

work. ISO collaborates closely with IEC on all matters of electrotechnical standardization.

International Standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

Draft Guides adopted by the responsible Committee or Group are circulated to the member bodies for

voting. Publication as a Guide requires approval by at least 75 % of the member bodies casting a vote.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO and IEC shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

ISO/IEC Guide 50 was prepared by a Joint Working Group of the ISO Committee on Consumer Policy

(COPOLCO) and the IEC Advisory Committee on Safety (ACOS). This third edition cancels and replaces

the second edition (ISO/IEC Guide 50:2002), which has been technically revised.

The main changes compared with the second edition are as follows:

— close alignment of the title and scope with the title and scope of ISO/IEC Guide 51;

— additional clarification that ISO/IEC Guide 50 is intended for standards developers, but that it can

also be used by other stakeholders;

— expansion of Clause 5 outlining the relationship between child development, behaviour and

unintentional harm;

— new structure of Clause 7 on hazards, and inclusion of new hazards that were not included in the

previous edition;

— addition of new Clause 8 dealing with the adequacy of safeguards.

iv © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

Introduction

0.1 Intended users of this Guide

This Guide provides guidance to those developing and revising standards, specifications and similar

publications. However, it contains important information that can be useful as background information

for, amongst others, designers, architects, manufacturers, service providers, educators, communicators

and policy makers.

This Guide provides useful information for auditors and safety inspectors in the absence of a specific

standard.

0.2 The reason for this Guide

Preventing injuries is a shared responsibility. The challenge is to develop products, including

manufactured articles, including their packaging, processes, structures, installations, services, built

environments or a combination of any of these which minimize the potential for causing deaths or

serious injuries to children. A significant aspect of this challenge is to balance safety with the need of

children to explore a stimulating environment and learn. Injury prevention can be addressed through

design, engineering, manufacturing controls, legislation, education and raising awareness.

0.3 Relevance of child safety

Child safety is a major concern for society, because child and adolescent injuries are a major cause of

[26]

death and disability in most countries. The joint WHO/UNICEF World Report on Child Injury Prevention

identifies unintentional injury as the leading cause of death for children over the age of 5. More than

830 000 children die each year from road traffic crashes, drowning, burns, falls and poisoning.

Children are born into an adult world, without experience or appreciation of risk, but with a natural

desire to explore. They can use products or interact with environments in ways not necessarily intended,

which are not necessarily regarded as “misuse”. Consequently, the potential for injury is particularly

great during childhood. Supervision might not always prevent or minimize significant injury. Therefore,

additional injury prevention strategies are often necessary.

Intervention strategies aimed at protecting children recognize that children are not little adults.

Children’s susceptibility to injury and the nature of their injuries differ from those of adults. Such

intervention strategies ideally also consider reasonably foreseeable use of products or surroundings.

Children interact with them in ways that reflect characteristics of child behaviour, which will vary

according to the child’s age and level of development. Intervention strategies intended to protect children

therefore often differ from those intended to protect adults.

0.4 Role of standards

Standards can play a key role in reducing and preventing injury because they have the unique potential

to:

— draw on technical expertise for design, manufacturing controls and testing,

— specify critical safety requirements, and

— inform through provisions for instructions, warnings, illustrations, symbols, etc.

NOTE In this Guide, the term “standard” includes other ISO/IEC publications, e.g. Technical Specifications

and Guides.

0.5 Structure of this Guide

This Guide provides additional information to ISO/IEC Guide 51. Whereas ISO/IEC Guide 51 provides

a structured approach to risk reduction within a general safety context, this Guide focuses on the

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved v

relationships between child development and harm from unintentional injury, and provides advice on

addressing hazards that children might encounter. This Guide is structured as follows:

a) Clause 4 describes a general approach to child safety, including the principles for a systematic way

to address hazards;

b) Clause 5 covers the relationship between child development and behaviour and unintentional

injury, including children’s anthropometry (see 5.1.2), motor (see 5.1.3), physiological (see 5.1.4) and

cognitive (see 5.1.5) development, and exploration strategies (see 5.1.6); the importance of applying

knowledge of child development to preventing harm is covered in 5.2; children’s development age

compared with chronological age is covered in 5.3;

c) Clause 6 covers the relevance of the child’s physical and social environments and special

considerations relating to the child’s sleeping environment;

d) Clause 7 describes hazards to which children might be exposed during their use of, or interaction

with, a product, along with specific suggestions for addressing those hazards;

e) Clause 8 describes a structured means of considering the adequacy of safeguards.

In addition, Annex A contains a checklist for assessing a standard. It provides an overview of hazards,

potential injuries and structured approaches to solutions. However, it is essential that it be read in

conjunction with the main body of this Guide, as it only gives a few examples of structured approaches.

Annex B lists some information on injury databases.

vi © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

GUIDE ISO/IEC GUIDE 50:2014(E)

Safety aspects — Guidelines for child safety in standards

and other specifications

1 Scope

This Guide provides guidance to experts who develop and revise standards, specifications and similar

publications. It aims to address potential sources of bodily harm to children from products that they

use, or with which they are likely to come into contact, even if not specifically intended for children.

This Guide does not provide guidance on the prevention of intentional harm (e.g. child abuse) or non-

physical forms of harm, such as psychological harm (e.g. intimidation).

This Guide does not address the economic consequences of the above.

NOTE The term “product” is defined in 3.5.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references.

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

3.1

carer

person who exercises responsibility, however temporarily, for an individual child’s safety (3.7)

Note 1 to entry: A carer is sometimes referred to as a “caregiver”.

EXAMPLE Parents; grandparents; siblings who have been given a limited responsibility over a child;

other relatives; adult acquaintances; babysitters; teachers; child-minders; youth leaders; sports coaches; camp

counsellors; day care workers.

3.2

child

person aged under 14 years

Note 1 to entry: Ages may vary according to local legislation; some standards may use different age limits.

Note 2 to entry: See 4.2 for more information.

3.3

harm

injury or damage to the health of people, or damage to property or the environment

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 3.1]

3.4

hazard

potential source of harm (3.3)

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 3.2]

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved 1

3.5

product

manufactured article, process, structure, installation, service, built environment or a combination of

any of these

Note 1 to entry: In the case of consumer goods, packaging (whether or not it is intended or likely to be retained as

part of the product) is considered an integral part of the product (see also 7.1).

3.6

risk

combination of the probability of occurrence of harm (3.3) and the severity of that harm

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 3.9, modified — Note 1 to entry has been deleted.]

3.7

safety

freedom from risk (3.6) which is not tolerable

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 3.14]

3.8

tolerable risk

level of risk (3.6) that is accepted in a given context based on the current values of society

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 3.15, modified — Note 1 to entry has been deleted.]

4 General approach to child safety

4.1 General

When developing or revising a standard for a product, standards developers should consider if and how

children are likely to interact with the products the standard is addressing, regardless of whether those

products are aimed specifically at children. The safety concepts that distinguish child safety from safety

in general are explained in this clause. These concepts are additional to the contents of ISO/IEC Guide 51.

4.2 Age descriptors used in this Guide

A number of age related terms referencing child development are in common use. They are not mutually

exclusive and, depending on context, may be used loosely or with precise meaning, as follows.

— The terms “babies” or “infants” usually refer to those not yet walking.

— The term “toddlers” usually refers to children who can walk, but whose ambulatory skills are not

fully developed and exhibit strong exploratory behaviour.

— The term “young children” often refers to those past the toddler stage, but still developing basic

skills, such as those aged 3 to 8 years. They are likely to have well-developed gross motor skills, are

beginning to perform some basic adult tasks, and are gradually subject to less supervision, but their

behaviour might still be impulsive and unpredictable. It is important to remember that there will

be significant differences between the skills and behaviours of children at the extremes of this age

range.

— The term “older children” refers to those who are not yet adolescents: the upper age limit can vary,

so the term can refer to those from approximately age 9 to age 12, 13 or 14. It is an age group that

is increasingly independent, is capable of performing most adult tasks (albeit with varying degrees

of competence) although they might still not act consistently and predictably, might react to peer

pressure, and might not fully understand the consequences of their actions. It is a period when there

can be an emotional conflict of wanting both security and independence. At the upper end of this age

group, children have a strong drive for independence and are likely to seek new experiences.

2 © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

4.3 Risk assessment

Risk assessment is an important step in any injury prevention strategy. It is critical to identify all events

or event chains that could result in harm for each hazard.

A general approach is outlined in ISO/IEC Guide 51, which defines the risk associated with a particular

hazardous situation as a function of the severity of harm that can result from the hazard, and the

probability of occurrence of that harm. Severity of harm and, in particular, probability of occurrence,

should be objectively determined and based on relevant facts that demonstrate causation, instead

of arbitrary and intuitive decision-making. When addressing child safety, the following factors need

special attention related to the risks for children:

a) their interactions with persons and products;

b) their development and behaviour;

c) degree of awareness, knowledge and experience of child and carer;

d) social, economic, and environmental factors; likelihood of being injured related to their physical

characteristics and behaviour;

e) degree of supervision by carer.

4.4 Preventing and reducing harm

4.4.1 Harm can result from hazards such as deprivation of vital needs, (e.g. oxygen, such as by drowning

or suffocation), transfer of energy (e.g. mechanical, thermal, electrical, radiation), or exposure to agents

(e.g. chemical, biological) greater than the body’s capacity to withstand (see Clause 7). It can be prevented

or reduced by intervening in the chain of events leading to, or following, their occurrence. Designing safe

products generally results in primary prevention.

4.4.2 Strategies may include one or more of the following:

— eliminating the hazard and/or exposure to the hazard (primary prevention, e.g. designing safer

products); for example, substituting non-flammable liquid for a flammable one);

— eliminating exposure to the hazard (primary prevention);

— reducing the probability of exposure to the hazard (secondary prevention, e.g. using child-resistant

packaging);

— reducing the severity of harm (secondary prevention, e.g. use of personal protective equipment or

reduction of temperature of domestic hot water);

— reducing the long-term effects of harm through approaches such as rescue, treatment or rehabilitation

(tertiary prevention).

NOTE An approach to risk reduction is also presented in ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 6.3.

4.4.3 In addition, strategies can be passive or active. Passive strategies work without the individual

having to take any action to be protected, whereas active strategies require the individual to take some

action to minimize the harm. Passive strategies that eliminate or guard against a hazard ensure a greater

likelihood of success than active strategies.

Improving product safety, i.e. eliminating or minimizing risks that may lead to significant injuries,

should start at the product design stage, aiming to incorporate a primary prevent approach or, if this

is not possible, a secondary prevent approach. Secondary prevention can include the provision of

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved 3

information for users about residual risks, those that might have to be addressed by users. Whenever

possible, product design should aim to incorporate passive prevention strategies.

NOTE An approach to risk reduction is also presented in ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 6.3.

Various sources can be used to identify the potential for harm associated with a product. These include,

but are not limited to:

— injury statistics;

— detailed information available from injury surveillance systems;

— research results;

— test data (although passing a test does not necessarily mean a product is free of hazards);

— investigations of case reports;

— complaint data;

— extrapolation of relevant data about hazardous characteristics from other types of products.

Surveillance data, recalls, and other similar actions in other jurisdictions should be considered.

CAUTION — The absence of reported harm does not necessarily mean that there is no hazard.

As harm to children is generally closely related to their developmental stage and their exposure to

hazards at various ages, it is important to sort child injury data by age group to identify the patterns

that emerge.

EXAMPLE 1 The number of burns from oven doors, scalds, poisoning by medicines and household chemicals,

and drowning peaks among children under 5 years of age.

EXAMPLE 2 Injuries associated with falls from playground equipment peak at 5 to 9 years.

EXAMPLE 3 Injuries associated with falls and impacts related to sports peak at 10 to 14 years.

The identification of countermeasures results from research and evaluation, particularly based on

injury data, child behaviour, engineering and biomechanics. Feedback, e.g. from consumers, can provide

valuable information about the need to redesign products.

When choosing preventive measures, it is important to recognize that tolerable risk for adults might

not apply to children. When introducing measures designed to protect adults it is essential to consider

increased and/or additional risks for children (e.g. passenger side air bags in cars).

Further information on injury surveillance systems is given in Annex B.

4.5 The “invisibility” of children

4.5.1 Children are “invisible”, i.e. their presence is difficult to detect, for several reasons:

— their small body size makes them less visible to adults;

— their lack of judgment to understand dangers and their unpredictable behaviour can place them in

hazardous situations that adults do not anticipate.

4.5.2 Human eyesight has limitations, such as limits in peripheral vision. Children out of the field of

vision of adults are at risk of being involved in serious accidents. For example:

— a child near a vehicle might be in the driver’s blind spot and be inadvertently hit by the vehicle;

— a child might jump out in front of a moving vehicle and be hit;

— a child might not be visible when another person opens or closes a door.

4 © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

4.5.3 Possible strategies to avoid or alleviate risks in blind spots should be considered, for example:

— preventing children from entering high-risk locations, such as driveways, by installing barriers or

swing-arm barriers to prevent them from crossing in front of a school bus without being seen by the

bus driver;

— eliminating blind spots on a vehicle by mounting a mirror or recognition system;

— extending a transparent window in a door to a lower level.

4.6 Needs of children with disabilities

A small but significant proportion of children have disabilities. Some children are born with a disabling

health condition or impairment, while others experience disability as a result of illness, injury or poor

nutrition. A number of children have a single impairment while others experience multiple impairments.

For example, a child with cerebral palsy might have mobility, communication and intellectual

impairments. The complex interaction between a health condition or impairment and environmental

and personal factors means that each child’s experience of disability is different.

IMPORTANT — For these reasons, advice from specialists should be sought.

For children with disabilities, requirements to meet their needs, in addition to those outlined in this

Guide, might be appropriate, although there might be situations when generic approaches are not

possible and individual approaches are required.

The term “disabilities” includes a wide range of conditions, varying in their nature, severity and impact.

Disabilities include, but are not limited to:

— behavioural and learning impairments;

— physical and growth impairments;

— sensory impairments;

— motor skill impairment.

This Guide does not provide detailed advice on how to minimize the risk and/or severity of unintentional

injuries among children with disabilities.

NOTE ISO/IEC Guide 71 addresses the needs of persons with disabilities in broad terms, but does not

specifically cover guidance relating to children with disabilities.

5 Safety considerations: child development, behaviour, and unintentional harm

5.1 Child development and behaviour

5.1.1 General

Children are not small adults. Inherent characteristics of children, including their stage of development,

together with their exposure to hazards, puts them at risk in ways different from adults. Developmental

stage broadly encompasses children’s size, shape, physiology, physical and cognitive ability, emotional

development and behaviour. These characteristics change quickly as children develop. Consequently,

parents and other carers often overestimate or underestimate children’s abilities at different stages of

development, thus exposing them to hazards. This situation is compounded by the fact that much of the

environment that surrounds children is designed for adults.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved 5

All the childhood characteristics described in this section need to be considered in determining potential

hazards associated with products. Keep in mind these characteristics can act in combination, increasing

the child’s risk. For example:

— exploratory behaviour might lead a child to climb a ladder;

— limited cognitive skills might prevent the child from recognizing that the ladder might be too high

or unstable;

— limited motor control might result in the child losing grip and falling.

The way children use and interact with products should be considered normal childhood behaviour. The

term “misuse” is misleading, and can lead to inappropriate decision-making regarding child hazards.

Survey evidence shows that children regularly use products that were not designed for them, such as

microwave ovens. When a child interacts with a product, it is difficult to make a distinction between

play, active learning or intended use. For safety reasons, it is not constructive to attempt to distinguish

between such interactions.

Safety considerations should provide an appropriate balance between risk and freedom for children

to explore a stimulating environment and to learn. The goal is to reduce the risk of harm by design in

accordance with their level of development.

5.1.2 Children’s body size and anthropometric data

Certain characteristics of children’s size and weight distribution make them particularly vulnerable to

harm. The nature of this harm might also be different from that experienced by adults.

Children’s size in relation to their surroundings makes it necessary to examine their anthropometry,

including overall heights as well as body part lengths, widths and circumferences. Anthropometric data

should be consulted in order to establish the normal distribution and safety margins. Children, like

adults, do not necessarily have consistent measurements for different parts of their bodies. For example,

a child measuring in the 95th percentile in height may have a head that is in the 50th percentile and hand

length in the 25th percentile. Children within an age group can have major differences in development

and size. The sexes experience growth spurts at different ages.

NOTE For useful references on anthropometric data, see Bibliography.

The following are examples where body size and weight distribution, as compared to adults, are factors

in harm.

a) In the case of thermal injuries, a given area of contact is typically a larger proportion of a child’s

surface area than is the case for an adult. In addition, children’s overall larger surface-area-to-body

mass ratio can result in a greater proportion of body fluids being lost from the burnt area.

b) Young children have a large head compared with their body size. Their high centre of mass increases

the likelihood of falls, e.g. from furniture or structures on which children might be sitting, climbing

or standing. Children often fall directly onto their head.

c) Another effect of the high centre of mass is that it also increases the likelihood of falling into pools,

buckets, toilets, bathtubs, etc., into which children are bending or reaching, thereby increasing the

risk of drowning.

d) The relatively large head size means that it requires a much larger space to pass through than the

rest of the body. Entrapment can occur when the body passes, feet first, through a gap through

which the head cannot.

e) The relatively large mass of the head increases the likelihood and severity of whiplash.

f) Children might be able to insert their fingers, hands or other parts of their body into small openings

and gaps to access rotating and moving parts or electrical and other hazards.

6 © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

g) Small quantities of substances that would not harm an adult can harm a child. They might be more

strongly affected than adults by exposure to chemical and radiation hazards due to their large

surface to mass ratio as well as their small body size.

5.1.3 Motor development

Motor development refers to the maturation process of gross and fine movements and coordination.

Understanding the development of children’s motor skills is essential to the design of products to

eliminate or mitigate harm.

The development process includes changes from primary involuntary reflex actions to deliberate,

goal-directed actions. Milestone achievements in the process include acquiring the strength and skill

to support the head, crouch, sit up, roll over, crawl, stand, climb, rock, walk and run, and the ability

to manipulate objects with hands and fingers. Until balance, control and strength have sufficiently

developed, children are particularly at risk of falling and getting into unsafe positions from which they

cannot escape.

EXAMPLE 1 When lying down, babies can move to the edge of a surface and roll off, but be unable to lift

themselves up. As a result, they can become wedged between products and suffer positional or compression

asphyxia.

EXAMPLE 2 Standing babies and toddlers can become entangled in cords, ribbons, or window dressings within

their reach. When they sit or slump, the cords can tighten around their neck, resulting in strangulation.

EXAMPLE 3 Climbing children can get clothing, accessories, and anything they wear (e.g. backpack, hair

accessory) caught in furniture items or protrusions. If they cannot extricate themselves, they can hang.

EXAMPLE 4 Children can fall from heights because they lose their balance or grip.

EXAMPLE 5 From about age three months, infants placed to sleep on their backs can turn over and suffocate if

the mattress or bedding is too soft.

5.1.4 Physiological development

In addition to their body size and motor functions, there are many other physiological functions that

are developing in children. These include sensory functions, biomechanical properties, reaction time,

metabolism and organ development.

Sensory development of children occurs over time. Visual development is slower than development of

other senses. Even at the stage when most children have vision similar to that of adults, they might

have narrower vision or have difficulty with depth perception. As a result, children will have difficulty

recognizing hazardous situations.

The following are examples where incomplete physiological development can be a factor in injuries:

a) children’s small body size and faster breathing rates result in their being particularly susceptible to

potentially toxic substances such as medications, chemicals and plants;

b) children’s biochemistry makes them susceptible to toxicity of chemicals, medications and plants not

toxic to adults;

c) the characteristics of children’s skin, including its thinness, make it more vulnerable to thermal

injury;

d) children’s bones are not fully developed, resulting in different responses to mechanical forces;

e) children are more susceptible to harm from intense light sources;

f) children are more sensitive to sound pressure.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved 7

5.1.5 Cognitive development

Children’s stage of cognitive development determines their ability or inability to understand the

consequences of their actions. Young children have limited ability to recognize hazards and they do not

consistently and reliably anticipate or respond to harmful consequences of hazardous conditions. Thus,

hazards obvious to adults are not so obvious for children.

At some stage in childhood, experience and teaching from parents and other carers begin to influence

the child’s behaviour, but this should not be relied upon when developing a product.

5.1.6 Exploration strategies

From early infancy, children are driven by an inborn drive to explore. Children’s exploration behaviour

can be classified in terms of basic strategies which correspond to their emerging abilities. Since children

experience a somewhat predictable sequence of physical and mental maturation, they also employ

predictable patterns of exploratory behaviour. These exploratory behaviours can result in the child

using products in ways that were not intended by the manufacturer.

One of the most frequently observed exploration strategies is object manipulation. In infancy, this often

involves handling and mouthing objects simultaneously. Exploratory mouthing is not just about eating.

Children’s mouths are relatively sensitive and mouthing provides children with feelings of pleasure

as well as alleviation of pain associated with teething. Exploratory mouthing requires basic motor

coordination (e.g. bringing one’s hand to the mouth). Children begin to explore objects in ways that

allow them to learn about their physical properties. With the emergence of more complex two-handed

coordination and other exploration strategies such as rotating, dropping, banging and throwing objects,

exploratory mouthing declines proportionally. However, some mouthing behaviour continues well

beyond the early stages of exploration.

As children’s sensory, motor, and cognitive skills improve, exploration of the environment gradually

becomes more sophisticated. Children continue to explore objects including their own bodies. Inserting

themselves into a large object or inserting small objects into their body cavities are common. Over time,

social play becomes a primary exploratory strategy for many children. Choices made by peers become

important motivating factors shaping exploration.

Adults understand that exploration is a process of “discovering the unknown” that involves risk. Children

of every age face additional risk, due to their limited risk perception and decision-making ability, poor

understanding of their own limitations and their physical and cognitive immaturity, all of which impact

their capacity to avoid danger. While children are capable of perceiving some risk, they are not able to

assess the risk involved in a potentially hazardous situation until they are capable of understanding

consequences (cause and effect) at around 7 to 8 years old.

Table 1 provides examples of children’s typical exploration strategies.

Table 1 — Examples of children’s typical exploration strategies

Exploration strategies Examples Age peak Illustrative examples

Mouthing Biting, sucking, gnawing, chewing, Birth to 3 years of age Soother (or pacifier), wooden blocks,

licking. washcloths, clothing, food made of

an inedible substance, teethers, toys,

button/coin batteries furniture,

window sills.

Rotating Children rotate an object as they visu- 6 months to 2 years of age Rattles, toys with water/beads in

ally inspect it. them, blocks, toys that make noise

when turned over.

Transferring hand to With increased motor co-ordination, 9 months to 2 years of age Balls, drumsticks, blocks, stacking

hand children become able to use both hands toys, plastic building blocks.

to rotate an object. This strategy allows

children to turn the object around

completely by passing it from one hand

to the other.

8 © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

Table 1 (continued)

Exploration strategies Examples Age peak Illustrative examples

Insertion (body into Begins when children become capable 6 months to 10 years of age Zipper pulls/loops, electrical outlets,

object) of isolating one finger. That is, when plastic tubes, openings of bottles,

they are able to extend one finger with- cardboard boxes, dog cages, railings

out all of their other fingers extending. and barrier slats.

Children then begin to explore objects

by putting their finger inside the

objects or running their finger along

the outside of the object. As children

grow, they will begin to insert other

body parts (hands, feet, legs, head, etc.)

and their entire bodies into objects as

they explore.

Insertion (object into Children explore the objects within 2 to 6 years of age Beads, stickers, peas, cotton buds,

body) their environments, as well as their buttons, modelling clay, modelling

own bodies, by placing objects into compound, small parts from toys.

their own body cavity.

Banging Children may bang objects to hear what 9 months to 5 years of age Pots and pans with wooden spoons,

sounds different objects can make. blocks, crayons, stacking toys,

It may also give feedback to children toys that make noise when banged

about the weight of the object. together or on hard surface.

Dropping Dropping of objects begins extremely 6 months to 3 years of age Feeding utensil, pacifier, balls, small

early in the life of a child. This type of toys, toys that bounce or make noise

exploration allows children to begin when dropped.

learning that objects continue to exist

even when out of their sight and that

they can have a certain level of control

over the actions of their parents or

caregivers.

Throwing Children begin throwing whatever they 1 to 4 years of a

...

GUIDE 50

Troisième édition

2014-12-15

Aspects liés à la sécurité — Principes

directeurs pour la sécurité des

enfants dans les normes et autres

spécifications

Safety aspects — Guidelines for child safety in standards and other

specifications

Numéro de référence

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

©

ISO/CEI 2014

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

DOCUMENT PROTÉGÉ PAR COPYRIGHT

© ISO/IEC 2014

Droits de reproduction réservés. Sauf indication contraire, aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite ni utilisée

sous quelque forme que ce soit et par aucun procédé, électronique ou mécanique, y compris la photocopie, l’affichage sur

l’internet ou sur un Intranet, sans autorisation écrite préalable. Les demandes d’autorisation peuvent être adressées à l’ISO à

l’adresse ci-après ou au comité membre de l’ISO dans le pays du demandeur.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Publié en Suisse

ii © ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

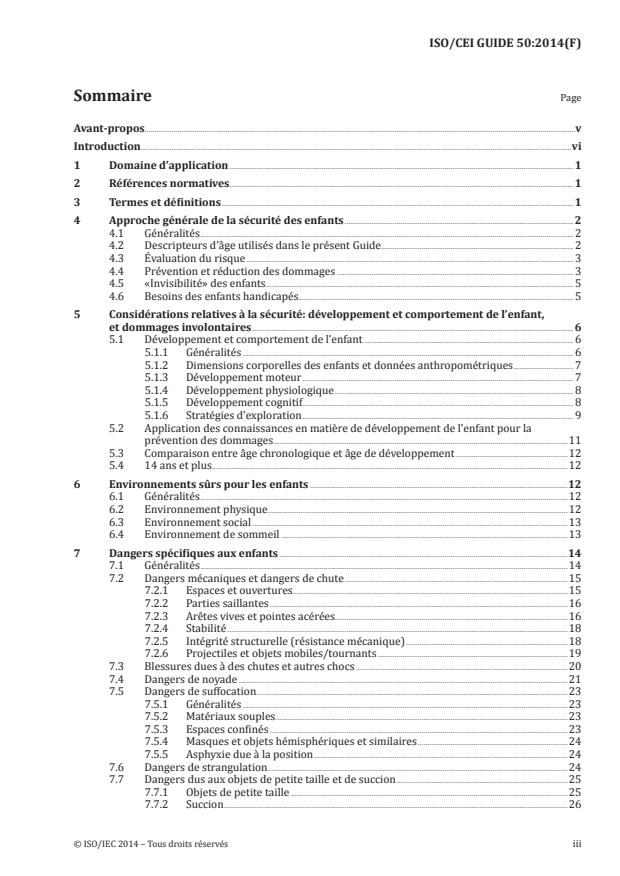

Sommaire Page

Avant-propos .v

Introduction .vi

1 Domaine d’application . 1

2 Références normatives . 1

3 Termes et définitions . 1

4 Approche générale de la sécurité des enfants . 2

4.1 Généralités . 2

4.2 Descripteurs d’âge utilisés dans le présent Guide . 2

4.3 Évaluation du risque . 3

4.4 Prévention et réduction des dommages . 3

4.5 «Invisibilité» des enfants . 5

4.6 Besoins des enfants handicapés . 5

5 Considérations relatives à la sécurité: développement et comportement de l’enfant,

et dommages involontaires . 6

5.1 Développement et comportement de l’enfant . 6

5.1.1 Généralités . 6

5.1.2 Dimensions corporelles des enfants et données anthropométriques . 7

5.1.3 Développement moteur . 7

5.1.4 Développement physiologique . 8

5.1.5 Développement cognitif . . 8

5.1.6 Stratégies d’exploration . 9

5.2 Application des connaissances en matière de développement de l’enfant pour la

prévention des dommages .11

5.3 Comparaison entre âge chronologique et âge de développement .12

5.4 14 ans et plus .12

6 Environnements sûrs pour les enfants .12

6.1 Généralités .12

6.2 Environnement physique .12

6.3 Environnement social .13

6.4 Environnement de sommeil .13

7 Dangers spécifiques aux enfants .14

7.1 Généralités .14

7.2 Dangers mécaniques et dangers de chute .15

7.2.1 Espaces et ouvertures . .15

7.2.2 Parties saillantes .16

7.2.3 Arêtes vives et pointes acérées .16

7.2.4 Stabilité .18

7.2.5 Intégrité structurelle (résistance mécanique) .18

7.2.6 Projectiles et objets mobiles/tournants .19

7.3 Blessures dues à des chutes et autres chocs .20

7.4 Dangers de noyade .21

7.5 Dangers de suffocation.23

7.5.1 Généralités .23

7.5.2 Matériaux souples .23

7.5.3 Espaces confinés .23

7.5.4 Masques et objets hémisphériques et similaires .24

7.5.5 Asphyxie due à la position .24

7.6 Dangers de strangulation .24

7.7 Dangers dus aux objets de petite taille et de succion .25

7.7.1 Objets de petite taille .25

7.7.2 Succion.26

© ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés iii

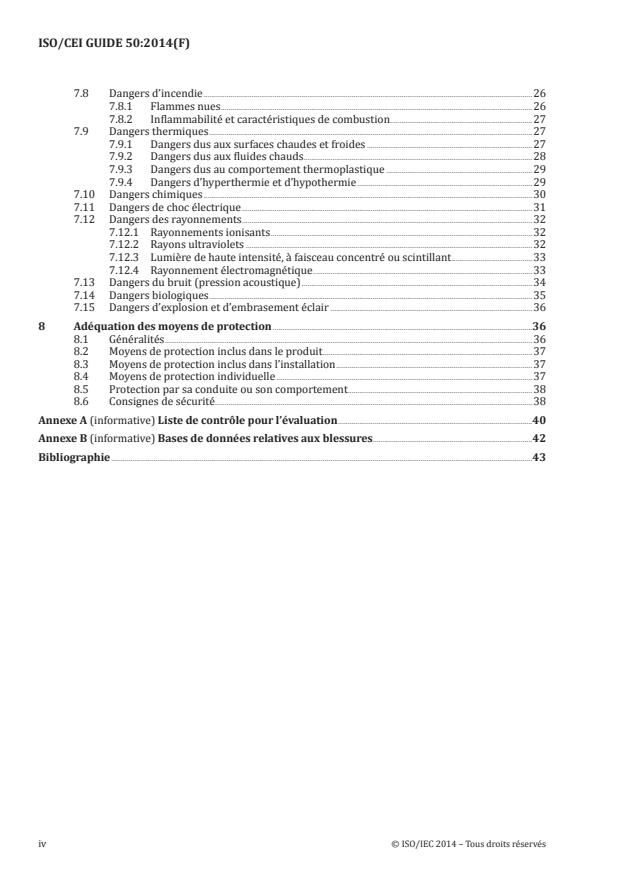

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

7.8 Dangers d’incendie .26

7.8.1 Flammes nues .26

7.8.2 Inflammabilité et caractéristiques de combustion .27

7.9 Dangers thermiques .27

7.9.1 Dangers dus aux surfaces chaudes et froides .27

7.9.2 Dangers dus aux fluides chauds.28

7.9.3 Dangers dus au comportement thermoplastique .29

7.9.4 Dangers d’hyperthermie et d’hypothermie .29

7.10 Dangers chimiques .30

7.11 Dangers de choc électrique .31

7.12 Dangers des rayonnements .32

7.12.1 Rayonnements ionisants .32

7.12.2 Rayons ultraviolets .32

7.12.3 Lumière de haute intensité, à faisceau concentré ou scintillant .33

7.12.4 Rayonnement électromagnétique .33

7.13 Dangers du bruit (pression acoustique) .34

7.14 Dangers biologiques .35

7.15 Dangers d’explosion et d’embrasement éclair .36

8 Adéquation des moyens de protection .36

8.1 Généralités .36

8.2 Moyens de protection inclus dans le produit .37

8.3 Moyens de protection inclus dans l’installation .37

8.4 Moyens de protection individuelle .37

8.5 Protection par sa conduite ou son comportement . .38

8.6 Consignes de sécurité .38

Annexe A (informative) Liste de contrôle pour l’évaluation .40

Annexe B (informative) Bases de données relatives aux blessures.42

Bibliographie .43

iv © ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

Avant-propos

L’ISO (Organisation internationale de normalisation) et l’IEC sont des fédérations mondiales d’organismes

nationaux de normalisation (comités membres de l’ISO et comités nationaux de l’IEC). L’élaboration

des Normes internationales est en général confiée aux comités techniques de l’ISO et de l’IEC. Chaque

comité membre intéressé par une étude a le droit de faire partie du comité technique créé à cet effet. Les

organisations internationales, gouvernementales et non gouvernementales, en liaison avec l’ISO ou l’IEC

participent également aux travaux. L’ISO collabore étroitement avec la Commission électrotechnique

internationale (IEC) en ce qui concerne la normalisation électrotechnique.

Les Normes internationales sont rédigées conformément aux règles données dans les Directives

ISO/IEC, Partie 2.

Les projets de Guides adoptés par le comité ou le groupe responsable sont soumis aux comités membres pour

vote. Leur publication comme Guides requiert l’approbation de 75 % au moins des comités membres votants.

L’attention est appelée sur le fait que certains des éléments du présent document peuvent faire l’objet

de droits de propriété intellectuelle ou de droits analogues. L’ISO et l’IEC ne sauraient être tenus pour

responsables de ne pas avoir identifié de tels droits de propriété et averti de leur existence.

Le Guide ISO/IEC 50 a été élaboré par un groupe de travail mixte du comité de l’ISO pour la politique en

matière de consommation (COPOLCO) et du comité consultatif de l’IEC pour la sécurité (ACOS). Cette

troisième édition annule et remplace la deuxième édition (Guide ISO/IEC 50:2002), qui a fait l’objet d’une

révision technique.

Les principales modifications par rapport à la deuxième édition sont les suivantes:

— un alignement étroit du titre et du domaine d’application sur le titre et le domaine d’application du

Guide ISO/IEC 51;

— l’ajout d’une précision sur le fait que le Guide ISO/IEC 50 est destiné aux rédacteurs de normes, mais

qu’il peut également être utilisé par d’autres parties prenantes;

— l’extension de l’Article 5 pour décrire la relation entre le développement de l’enfant, son comportement

et les dommages non intentionnels;

— une nouvelle structure de l’Article 7 relatif aux dangers, et l’inclusion de nouveaux dangers qui

n’étaient pas inclus dans l’édition précédente;

— l’ajout d’un nouvel Article 8 traitant de l’adéquation des moyens de protection.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés v

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

Introduction

0.1 Utilisateurs prévus du présent Guide

Le présent Guide fournit des lignes directrices aux personnes concernées par l’élaboration et la révision

de normes, de spécifications et de publications similaires. Il contient toutefois des informations

importantes qui peuvent être utiles, à titre d’informations de base, notamment aux concepteurs,

architectes, fabricants, prestataires de services, éducateurs, communicants, ainsi qu’aux personnes

chargées de définir les politiques en matière de sécurité.

En l’absence de norme spécifique, le présent Guide fournit des informations utiles aux auditeurs et aux

inspecteurs de la sécurité.

0.2 Motif du présent Guide

La prévention des blessures est une responsabilité partagée. Le défi est de développer des produits,

comprenant des articles manufacturés, y compris leur emballage, des processus, des structures, des

installations, des services, des environnements construits ou toute combinaison de ceux-ci permettant

de réduire au minimum la possibilité de provoquer le décès ou de graves blessures chez les enfants. Un

aspect important de ce défi est de trouver un équilibre entre la sécurité et le besoin pour les enfants

d’explorer un environnement stimulant et d’apprendre. La prévention des blessures peut être traitée

par la conception, la technique, la maîtrise de la fabrication, la législation, l’éducation et en augmentant

la prise de conscience.

0.3 Importance de la sécurité des enfants

La sécurité des enfants est une préoccupation majeure de la société dans la mesure où, chez l’enfant et

l’adolescent, les blessures sont l’une des principales causes de décès et d’invalidité dans la plupart des

pays. Le rapport conjoint de l’OMS et de l’UNICEF, Rapport mondial sur la prévention des traumatismes

[26]

chez l’enfant identifie les blessures involontaires comme la principale cause de décès chez les enfants

de plus de 5 ans. Plus de 830 000 enfants meurent chaque année par suite d’accidents de la circulation,

de noyades, de brûlures, de chutes et d’empoisonnements.

Les enfants naissent dans un monde d’adultes, sans expérience ni appréciation du risque, mais avec un

désir naturel d’exploration. Ils peuvent utiliser des produits ou interagir avec des environnements d’une

manière qui n’était pas nécessairement prévue, mais qui n’est pas nécessairement considérée comme un

«mauvais usage». Il en résulte que le risque de blessure est particulièrement grand au cours de l’enfance.

La surveillance ne permet pas toujours d’éviter ou minimiser les blessures importantes. Par conséquent,

des stratégies complémentaires de prévention des blessures sont souvent nécessaires.

Les stratégies d’intervention visant à la protection des enfants reconnaissent que les enfants ne sont pas

de petits adultes. La vulnérabilité des enfants aux blessures et la nature de leurs blessures diffèrent de

celles des adultes. Idéalement, de telles stratégies d’intervention tiennent également compte de l’usage

raisonnablement prévisible des produits ou de l’environnement. Les enfants interagissent avec ceux-

ci d’une manière qui reflète les caractéristiques de leur comportement, qui varieront en fonction de

leur âge et de leur niveau de développement. Par conséquent, les stratégies d’intervention destinées à

protéger les enfants diffèrent souvent de celles destinées à protéger les adultes.

0.4 Rôle des normes

Les normes peuvent jouer un rôle fondamental dans la réduction et la prévention des blessures dans la

mesure où elles ont le potentiel unique:

— de s’appuyer sur l’expertise technique pour la conception, la maîtrise de la fabrication et les essais,

— de spécifier des exigences critiques pour la sécurité, et

— d’informer par le biais de dispositions d’instructions, d’avertissements, d’illustrations, de symboles, etc.

NOTE Dans le présent Guide, le terme «norme» inclut d’autres publications de l’ISO ou de l’IEC, telles que les

Spécifications techniques et les Guides.

vi © ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

0.5 Structure du présent Guide

Le présent Guide fournit des informations venant en complément du Guide ISO/IEC 51. Alors que le

Guide ISO/IEC 51 fournit une approche structurée de la réduction du risque dans un contexte général

de sécurité, le présent Guide se concentre sur les relations entre le développement de l’enfant et les

dommages causés par un traumatisme involontaire, et donne des conseils sur le traitement des dangers

auxquels peuvent être confrontés les enfants. Le présent Guide est organisé comme suit:

a) l’Article 4 décrit une approche générale de la sécurité des enfants, y compris les principes d’un

traitement systématique des dangers;

b) l’Article 5 traite de la relation entre le développement et le comportement de l’enfant et les

blessures involontaires, y compris l’anthropométrie des enfants (voir 5.1.2), leur développement

moteur (voir 5.1.3), physiologique (voir 5.1.4) et cognitif (voir 5.1.5) et les stratégies d’exploration

(voir 5.1.6); l’importance de l’application des connaissances en matière de développement de l’enfant

pour la prévention des dommages est traitée en 5.2; la comparaison entre l’âge de développement

des enfants et l’âge chronologique est traitée en 5.3;

c) l’Article 6 traite de la pertinence des environnements physique et social de l’enfant ainsi que des

considérations particulières relatives à l’environnement de sommeil de l’enfant;

d) l’Article 7 décrit les dangers auxquels les enfants peuvent être exposés lors de l’utilisation ou de

l’interaction avec un produit, ainsi que les suggestions spécifiques pour la prise en compte de ces dangers;

e) l’Article 8 décrit une méthode structurée permettant d’évaluer l’adéquation des moyens de protection.

En outre, l’Annexe A contient une liste de contrôle pour l’évaluation d’une norme. Elle offre une vision

globale des dangers, des blessures potentielles et des approches structurées de solutions. Cependant,

il est essentiel de la lire conjointement avec le texte principal du présent Guide car seuls quelques

exemples d’approches structurées y sont donnés. L’Annexe B donne certaines informations sur les bases

de données relatives aux blessures.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés vii

GUIDE ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

Aspects liés à la sécurité — Principes directeurs pour

la sécurité des enfants dans les normes et autres

spécifications

1 Domaine d’application

Le présent Guide fournit des lignes directrices aux experts concernés par l’élaboration et la révision

de normes, de spécifications et de publications similaires. Il vise à traiter des sources potentielles de

dommages corporels pour les enfants, présentes dans les produits qu’ils utilisent ou avec lesquels ils

sont susceptibles d’entrer en contact, même s’ils ne sont pas spécifiquement destinés à des enfants.

Le présent Guide ne fournit pas de lignes directrices concernant la prévention des dommages

intentionnels (par exemple, violence faite aux enfants) ou de formes non physiques de dommages, telles

que les dommages psychologiques (par exemple, intimidation).

Le présent Guide ne traite pas des conséquences économiques de ce qui précède.

NOTE Le terme «produit» est défini en 3.5.

2 Références normatives

Il n’y a pas de références normatives.

3 Termes et définitions

Pour les besoins du présent document, les termes et définitions suivants s’appliquent.

3.1

personne qui s’occupe des enfants

personne ayant la responsabilité, même temporaire, de la sécurité (3.7) d’un enfant

Note 1 à l’article: La personne qui s’occupe des enfants est parfois appelée « garde d’enfant ».

EXEMPLE Parents, grands-parents, frères ou sœurs auxquels on a attribué de façon limitée la responsabilité

d’un enfant, autres parents, proches adultes, gardes d’enfants, enseignants, assistantes maternelles, animateurs,

entraîneurs sportifs, moniteurs de camp de vacances, employés de crèches.

3.2

enfant

personne de moins de 14 ans

Note 1 à l’article: L’âge peut varier selon la législation locale; certaines normes peuvent utiliser des limites

d’âge différentes.

Note 2 à l’article: Voir 4.2 pour de plus amples informations.

3.3

dommage

blessure physique ou atteinte à la santé des personnes, ou atteinte aux biens ou à l’environnement

[SOURCE: Guide ISO/IEC 51:2014, 3.1]

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

3.4

danger

source potentielle de dommage (3.3)

[SOURCE: Guide ISO/IEC 51:2014, 3.2]

3.5

produit

article manufacturé, processus, structure, installation, service, environnement construit ou toute

combinaison de ceux-ci

Note 1 à l’article: Dans le cas des produits de consommation, l’emballage (qu’il soit ou non destiné ou susceptible

d’être conservé comme une partie du produit) est considéré comme faisant partie intégrante du produit (voir

également 7.1).

3.6

risque

combinaison de la probabilité de la survenue d’un dommage (3.3) et de sa gravité

[SOURCE: Guide ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 3.9, modifié — La Note 1 à l’article a été supprimée.]

3.7

sécurité

absence de risque (3.6) intolérable

[SOURCE: Guide ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 3.14]

3.8

risque tolérable

niveau de risque (3.6) accepté dans un contexte donné et fondé sur les valeurs admises par la société

[SOURCE: Guide ISO/IEC 51:2014, 3.15, modifié — La Note 1 à l’article a été supprimée.]

4 Approche générale de la sécurité des enfants

4.1 Généralités

Lors de l’élaboration ou de la révision d’une norme relative à un produit, il convient que les rédacteurs de

la norme considèrent si et comment les enfants sont susceptibles d’interagir avec les produits couverts

par la norme, que ces produits soient ou non spécifiquement destinés aux enfants. Les concepts de

sécurité qui distinguent la sécurité des enfants de la sécurité en général sont explicités dans le présent

article. Ces concepts viennent s’ajouter au contenu du Guide ISO/IEC 51.

4.2 Descripteurs d’âge utilisés dans le présent Guide

De nombreux termes liés à l’âge se rapportant au développement de l’enfant sont d’usage courant. Ils

ne sont pas mutuellement exclusifs et, selon le contexte, peuvent être utilisés au sens large ou avec une

signification précise, comme suit.

— Les termes «bébés» et «nourrissons» se rapportent généralement aux enfants qui ne marchent pas

encore.

— Le terme «tout-petits» se rapporte généralement à des enfants capables de marcher, mais dont

les compétences en termes de marche ne sont pas entièrement développées et qui présentent un

comportement exploratoire marqué.

— Le terme «jeunes enfants» se rapporte souvent à des enfants tels que les enfants de 3 ans à 8 ans

ayant dépassé le stade de tout-petit, mais développant encore leur adresse. Il est probable qu’ils

présentent une motricité globale bien développée, commencent à accomplir certaines tâches

élémentaires d’adulte et fassent progressivement l’objet de moins de surveillance, mais leur

2 © ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

comportement peut encore être impulsif et imprévisible. Il est important de se rappeler qu’il y aura

des différences significatives entre l’adresse et les comportements des enfants situés aux extrémités

de cette tranche d’âge.

— Le terme «grands enfants» se rapporte aux enfants qui ne sont pas encore des adolescents: la limite

supérieure d’âge pouvant varier, le terme peut se rapporter aux enfants approximativement âgés

de 9 ans à 12, 13 ou 14 ans. Il s’agit d’un groupe d’âge dans lequel les enfants sont de plus en plus

indépendants, sont capables de réaliser la plupart des tâches d’adulte (mais avec des degrés variables

de compétence) bien qu’ils puissent encore ne pas agir de façon cohérente et prévisible, réagir à la

pression de leurs camarades et ne pas comprendre totalement les conséquences de leurs actes. Il

s’agit d’une période où il peut y avoir un conflit émotionnel entre vouloir la sécurité et l’indépendance.

À l’extrémité supérieure de ce groupe d’âge, les enfants ont une grande soif d’indépendance et sont

susceptibles de rechercher de nouvelles expériences.

4.3 Évaluation du risque

L’évaluation du risque est une étape importante de toute stratégie de prévention des blessures. Elle est

essentielle pour identifier pour chaque danger tous les événements ou chaînes d’événements pouvant

provoquer des dommages.

Une approche générale est esquissée dans le Guide ISO/IEC 51, qui définit le risque associé à une

situation dangereuse particulière comme une combinaison de la gravité du dommage pouvant résulter

du danger et de la probabilité de survenue de ce dommage. Il convient que la gravité d’un dommage et, en

particulier, sa probabilité de survenue soient déterminées objectivement sur la base de faits pertinents

démontrant la causalité, plutôt que d’une décision prise de façon arbitraire et intuitive. Lorsque l’on

traite de la sécurité des enfants, les facteurs suivants nécessitent une attention particulière en ce qui

concerne les risques pour les enfants:

a) leurs interactions avec les personnes et les produits;

b) leur développement et leur comportement;

c) le degré de conscience, de connaissance et d’expérience de l’enfant et de la personne qui s’occupe de

l’enfant;

d) les facteurs sociaux, économiques et environnementaux; la probabilité d’être blessés en raison de

leurs caractéristiques physiques et de leur comportement;

e) le niveau de surveillance par la personne qui s’occupe de l’enfant.

4.4 Prévention et réduction des dommages

4.4.1 Les dommages peuvent résulter d’une privation d’éléments vitaux (par exemple, oxygène en cas

de noyade ou de suffocation), du transfert d’énergie (par exemple, mécanique, thermique, électrique,

rayonnement) ou d’une exposition à des agents (par exemple, chimiques, biologiques) supérieure

à la capacité de résistance du corps (voir Article 7). Ces dommages peuvent être évités ou réduits en

intervenant dans la chaîne des événements à la source ou consécutifs à la survenue. La conception de

produits sûrs aboutit généralement à une prévention primaire.

4.4.2 Les stratégies peuvent inclure un ou plusieurs des éléments suivants:

— élimination du danger et/ou exposition au danger (prévention primaire, par exemple, la conception

de produits sûrs); par exemple, par la substitution de liquide inflammable par un liquide

ininflammable;

— élimination de l’exposition au danger (prévention primaire);

— réduction de la probabilité d’exposition au danger (prévention secondaire, par exemple, utilisation

d’un emballage à l’épreuve des enfants);

© ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés 3

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

— réduction de la gravité des dommages (prévention secondaire, par exemple, utilisation d’un

équipement de protection individuelle ou réduction de la température de l’eau chaude sanitaire);

— réduction des effets à long terme du dommage par des approches telles qu’un sauvetage, un

traitement ou une rééducation (prévention tertiaire).

NOTE Une approche de la réduction du risque est également présentée dans le Guide ISO/IEC 51:2014, 6.3.

4.4.3 Les stratégies peuvent, en outre, être passives ou actives. Les stratégies passives ne nécessitent

aucune action de la part de l’individu à protéger alors que les stratégies actives nécessitent une certaine

action de l’individu pour réduire les dommages. Les stratégies passives qui éliminent ou qui assurent une

protection contre le danger garantissent généralement une plus grande probabilité de réussite que les

stratégies actives.

Il convient que l’amélioration de la sécurité du produit, par exemple, en éliminant ou en réduisant les

risques pouvant conduire à des blessures très graves, débute dès le stade de la conception du produit,

visant à incorporer une approche de la prévention primaire ou, si cela n’est pas possible, une approche de

la prévention secondaire. La prévention secondaire peut comprendre la fourniture d’informations aux

utilisateurs concernant les risques résiduels, ceux qui sont susceptibles d’être traités par les utilisateurs.

Chaque fois que possible, il convient que la conception du produit vise à incorporer les stratégies de

prévention passives.

NOTE Une approche de la réduction des risques est également présentée dans l’ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014, 6.3.

Différentes sources peuvent être utilisées pour identifier le potentiel de dommage associé à un produit.

Ces sources incluent, sans toutefois s’y limiter:

— les statistiques disponibles sur les blessures;

— les informations détaillées fournies par les systèmes de surveillance des traumatismes;

— les résultats de recherche;

— les données d’essai (bien que le fait de réussir un essai ne signifie pas nécessairement qu’un produit

est exempt de dangers);

— les enquêtes sur des affaires;

— les données relatives aux plaintes signalées;

— l’extrapolation des données pertinentes sur les caractéristiques dangereuses provenant d’autres

types de produits. Il convient de prendre en compte les données de surveillance, les rappels et

autres actions similaires engagées dans d’autres juridictions.

ATTENTION — L’absence de rapports sur les dommages ne signifie pas nécessairement qu’il y a

absence de danger.

Dans la mesure où les dommages subis par les enfants sont en général étroitement liés à leur stade de

développement et à leur exposition à des âges différents aux dangers, il est important de trier les données

relatives aux blessures subies par les enfants par groupe d’âge afin d’identifier les scénarii émergents.

EXEMPLE 1 Le nombre de brûlures dues aux portes de fours, les brûlures occasionnées par l’eau bouillante,

l’empoisonnement par des médicaments et des produits chimiques ménagers, ainsi que la noyade, présentent des

taux maximaux chez les enfants de moins de 5 ans.

EXEMPLE 2 Les blessures dues aux chutes du haut d’un équipement d’aire de jeux présentent un taux maximal

chez les enfants de 5 à 9 ans.

EXEMPLE 3 Les blessures résultant de chutes et de chocs associés à la pratique des sports présentent un taux

maximal chez les enfants de 10 à 14 ans.

L’identification de contre-mesures est le résultat d’une recherche et d’une évaluation, particulièrement

sur la base des données relatives aux traumatismes, du comportement des enfants, de l’ingénierie et

4 © ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

de la biomécanique. Le retour d’informations, par exemple, des consommateurs, peut fournir des

informations intéressantes sur la nécessité de revoir la conception des produits.

Lors du choix des mesures de prévention, il est important de reconnaître qu’un risque tolérable pour

les adultes peut ne pas s’appliquer aux enfants. En introduisant des mesures destinées à protéger les

adultes, il est essentiel de prendre en considération des risques accrus et/ou supplémentaires pour les

enfants (par exemple, les sacs gonflables (airbags) de voitures du côté du passager).

Des informations supplémentaires sur les systèmes de surveillance des traumatismes sont données

à l’Annexe B.

4.5 «Invisibilité» des enfants

4.5.1 Les enfants sont «invisibles», c’est-à-dire que leur présence est difficile à détecter, pour

plusieurs raisons:

— leurs petites dimensions corporelles les rendent moins visibles par les adultes;

— leur manque de jugement dans la compréhension des dangers et leur comportement imprévisible

peuvent les placer dans des situations dangereuses non anticipées par les adultes.

4.5.2 La vision humaine est limitée, notamment la vision périphérique. Les enfants se trouvant hors du

champ de vision des adultes risquent d’être impliqués dans des accidents graves, par exemple:

— un enfant se trouvant à proximité d’un véhicule peut se trouver dans l’angle mort du conducteur et

être heurté accidentellement par le véhicule;

— un enfant peut surgir face à un véhicule en mouvement et être heurté;

— un enfant peut ne pas être visible lorsqu’une autre personne ouvre ou ferme une porte.

4.5.3 Il convient d’étudier les stratégies possibles pour éviter ou réduire les risques dans les angles

morts, par exemple:

— empêcher les enfants de pénétrer dans des zones à risque élevé, telles que des voies d’accès, en

installant des barrières ou des barrières à bras oscillant pour les empêcher de traverser devant un

bus scolaire sans être vus par le conducteur du bus;

— supprimer les angles morts sur un véhicule en montant un miroir ou un système de reconnaissance;

— étendre la vitre transparente d’une porte jusqu’à un niveau plus bas.

4.6 Besoins des enfants handicapés

Une proportion faible, mais significative, des enfants présente un handicap. Certains enfants sont nés

avec une maladie invalidante ou un handicap, alors que d’autres sont devenus handicapés à la suite d’une

maladie, d’un traumatisme ou de malnutrition. De nombreux enfants ne présentent qu’un seul handicap,

mais d’autres présentent de multiples handicaps. Par exemple, un enfant atteint de paralysie cérébrale

peut présenter des troubles moteurs, des troubles de la communication et une déficience intellectuelle.

L’interaction complexe entre l’état de santé ou le handicap et les facteurs environnementaux et personnels

signifie que le vécu du handicap est différent pour chaque enfant.

IMPORTANT — Pour ces raisons, il convient de demander conseil à des spécialistes.

En ce qui concerne les enfants handicapés, des exigences visant à répondre à leurs besoins peuvent

être appropriées, en complément de celles spécifiées dans le présent Guide, bien qu’il puisse exister des

situations dans lesquelles les approches générales ne sont pas possibles et des approches individuelles

sont requises.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – Tous droits réservés 5

ISO/CEI GUIDE 50:2014(F)

Le terme «handicap» couvre un large éventail d’états, dont la nature, la gravité et l’impact sont variables.

Les handicaps comprennent, sans toutefois s’y limiter:

— les troubles du comportement et de l’apprentissage;

— les handicaps physiques et les retards de croissance;

— les déficiences sensorielles;

— les déficiences de la motricité.

Le présent Guide ne fournit pas de conseils détaillés sur la façon de réduire au minimum le risque et/ou

la gravité des blessures involontaires des enfants handicapés.

NOTE Le Guide ISO/IEC 71 traite de façon générale les besoins des personnes handicapées, mais ne fournit

pas spécifiquement de lignes directrices concernant les enfants handicapés.

5 Considérations relatives à la sécurité: développement et comportement de

l’enfant, et dommages involontaires

5.1 Développement et comportement de l’enfant

5.1.1 Généralités

Les enfants ne sont pas de petits adultes. Les caractéristiques intrinsèques des enfants, y compris leur

stade de développement ainsi que leur exposition aux dangers, leur font courir des risques différents de

ceux auxquels sont exposés les adultes. Le stade de développement englobe généralement la taille et la

constitution de l’enfant, sa physiologie, sa capacité physique et cognitive, son développement affectif et

son comportement. Ces caractéristiques varient rapidement à mesure du développement de l’enfant. Par

conséquent, les parents et autres personnes qui s’occupent des enfants surestiment ou sous-estiment

souvent les capacités des enfants à différents stades de développement, les exposant ainsi à des dangers.

Cette situation est aggravée par le fait qu’une grande partie de l’environnement des enfants est conçue

pour les adultes.

Pour la détermination des dangers potentiels associés aux produits, toutes les caractéristiques de l’enfance

décrites dans le présent article doivent être prises en considération. Il faut garder à l’esprit le fait que ces

caractéristiques peuvent se combiner entre elles, accroissant par là le risque pour l’enfant. Par exemple: