SIST-TP ISO/TR 18792:2009

Lubrication of industrial gear drives

Lubrication of industrial gear drives

ISO/TR 18792:2008 is designed to provide currently available technical information with respect to the lubrication of industrial gear drives up to pitch line velocities of 30 m/s. It is intended to serve as a general guideline and source of information about the different types of gear, and lubricants, and their selection for gearbox design and service conditions.

Lubrification des entraînements par engrenages industriels

Mazanje industrijskih zobniških gonil

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 06-Apr-2009

- Technical Committee

- ISEL - Mechanical elements

- Current Stage

- 6060 - National Implementation/Publication (Adopted Project)

- Start Date

- 26-Mar-2009

- Due Date

- 31-May-2009

- Completion Date

- 07-Apr-2009

Overview

ISO/TR 18792:2008 - Lubrication of industrial gear drives - is a technical report providing current technical information and guidance for the lubrication of industrial gearboxes up to a pitch line velocity of 30 m/s. It is an informative (non‑normative) source intended for gear manufacturers, gearbox users, maintenance and service personnel, and lubricant manufacturers/distributors. The report focuses on lubricant types, selection principles, lubrication systems and service practices for a wide range of gear types (excluding automotive transmissions).

Key Topics

ISO/TR 18792:2008 covers practical and technical aspects of gear lubrication, including:

- Basics and failure modes

- Tribo‑technical parameters of gears and how lubrication affects wear, scuffing, micropitting and pitting.

- Lubricant composition

- Base fluids, thickeners, additives and solid lubricants; how chemical properties influence protection and life.

- Friction, temperature and film formation

- Effects of operating temperature, shear and lubricant film on gear performance.

- Lubrication regimes and methods

- Splash (immersion), transfer, spray, oil‑stream, oil‑mist, brush and centralized systems; guidance for open gearing vs enclosed gear units.

- Viscosity selection

- Practical tables and guidelines for selecting lubricant viscosity (parallel, bevel - not hypoid - worm and girth gears), with ISO viscosity grade guidance at operating temperatures.

- Test methods and condition monitoring

- Gear test methods, functional lubricant tests and recommendations for oil sampling and on‑line monitoring.

- Gearbox service and maintenance

- Initial fill and change intervals, best practices for lubricant change, sample analysis and fault diagnosis.

Applications

This Technical Report is used to:

- Select appropriate gear oils, greases and lubricating compounds for new gearbox designs and retrofits.

- Define lubrication system type (splash, circulation, spray, mist) based on pitch line velocity, gear type and duty cycle.

- Develop maintenance schedules: initial fill procedures, oil change intervals and oil‑condition monitoring programs.

- Support gearbox troubleshooting by linking lubricant properties and operating conditions to failure modes.

- Inform lubricant manufacturers and distributors about industry needs for additive packages and base fluid performance.

Who benefits:

- Gearbox designers and gear manufacturers

- Industrial maintenance teams and reliability engineers

- Lubricant formulators and suppliers

- Plant managers in mining, cement, steel, power generation and other heavy industries

Related Standards

ISO/TR 18792:2008 was prepared by ISO/TC 60 (Gears) and complements other ISO gear and lubrication standards (refer to ISO technical committee publications for related normative standards and test methods).

Frequently Asked Questions

SIST-TP ISO/TR 18792:2009 is a technical report published by the Slovenian Institute for Standardization (SIST). Its full title is "Lubrication of industrial gear drives". This standard covers: ISO/TR 18792:2008 is designed to provide currently available technical information with respect to the lubrication of industrial gear drives up to pitch line velocities of 30 m/s. It is intended to serve as a general guideline and source of information about the different types of gear, and lubricants, and their selection for gearbox design and service conditions.

ISO/TR 18792:2008 is designed to provide currently available technical information with respect to the lubrication of industrial gear drives up to pitch line velocities of 30 m/s. It is intended to serve as a general guideline and source of information about the different types of gear, and lubricants, and their selection for gearbox design and service conditions.

SIST-TP ISO/TR 18792:2009 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 21.200 - Gears; 21.260 - Lubrication systems. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

SIST-TP ISO/TR 18792:2009 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-maj-2009

Mazanje industrijskih zobniških gonil

Lubrication of industrial gear drives

Lubrification des entraînements par engrenages industriels

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: ISO/TR 18792:2008

ICS:

21.200 Gonila Gears

21.260 Mazalni sistemi Lubrication systems

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

TECHNICAL ISO/TR

REPORT 18792

First edition

2008-12-15

Lubrication of industrial gear drives

Lubrification des entraînements par engrenages industriels

Reference number

©

ISO 2008

PDF disclaimer

This PDF file may contain embedded typefaces. In accordance with Adobe's licensing policy, this file may be printed or viewed but

shall not be edited unless the typefaces which are embedded are licensed to and installed on the computer performing the editing. In

downloading this file, parties accept therein the responsibility of not infringing Adobe's licensing policy. The ISO Central Secretariat

accepts no liability in this area.

Adobe is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated.

Details of the software products used to create this PDF file can be found in the General Info relative to the file; the PDF-creation

parameters were optimized for printing. Every care has been taken to ensure that the file is suitable for use by ISO member bodies. In

the unlikely event that a problem relating to it is found, please inform the Central Secretariat at the address given below.

© ISO 2008

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from either ISO at the address below or

ISO's member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Contents Page

Foreword. v

Introduction . vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Terms and definitions. 1

3 Basics of gear lubrication and failure modes.3

3.1 Tribo-technical parameters of gears. 3

3.2 Gear lubricants. 5

3.3 Base fluid components . 6

3.4 Thickeners . 8

3.5 Chemical properties of additives . 9

3.6 Solid lubricants . 10

3.7 Friction and temperature . 10

3.8 Lubricating regime. 11

3.9 Lubricant influence on gear failure. 11

4 Test methods for lubricants . 15

4.1 Gear tests . 15

4.2 Other functional tests. 16

5 Lubricant viscosity selection . 19

5.1 Guideline for lubricant selection for parallel and bevel gears (not hypoid). 19

5.2 Guideline for lubricant selection for worm gears. 24

5.3 Guideline for lubricant selection for open girth gears. 24

6 Lubrication principles for gear units . 26

6.1 Enclosed gear units. 27

6.2 Open gearing. 34

7 Gearbox service information . 39

7.1 Initial lubricant fill and initial lubricant change period . 39

7.2 Subsequent lubricant change interval. 39

7.3 Recommendations for best practice for lubricant changes. 40

7.4 Used gear lubricant sample analysis. 41

Bibliography . 52

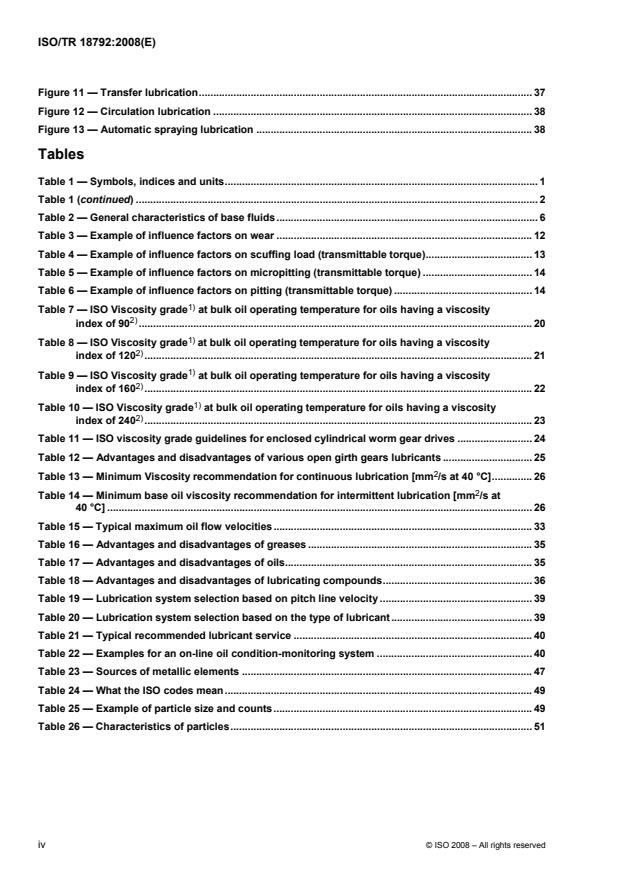

Figures

Figure 1 — Load and speed distribution along the path of contact. 4

Figure 2 — Scraping edge at the ingoing mesh . 5

Figure 3 — Schematic diagram of shear effects on thickeners. 9

Figure 4 — Mechanisms of surface protection for oils with additives. 11

Figure 5 — Examples of gear oil wear test results. 15

Figure 6 — Immersion of gear wheels . 27

Figure 7 — Immersion depth for different inclinations of the gearbox. 29

Figure 8 — Immersion of gear wheels in a multistage gearbox . 30

Figure 9 — Examples of circuit design, combination of filtration and cooling systems . 34

Figure 10 — Immersion lubrication. 37

Figure 11 — Transfer lubrication. 37

Figure 12 — Circulation lubrication . 38

Figure 13 — Automatic spraying lubrication . 38

Tables

Table 1 — Symbols, indices and units. 1

Table 1 (continued) . 2

Table 2 — General characteristics of base fluids. 6

Table 3 — Example of influence factors on wear . 12

Table 4 — Example of influence factors on scuffing load (transmittable torque). 13

Table 5 — Example of influence factors on micropitting (transmittable torque) . 14

Table 6 — Example of influence factors on pitting (transmittable torque) . 14

1)

Table 7 — ISO Viscosity grade at bulk oil operating temperature for oils having a viscosity

2)

index of 90 . 20

1)

Table 8 — ISO Viscosity grade at bulk oil operating temperature for oils having a viscosity

2)

index of 120 . 21

1)

Table 9 — ISO Viscosity grade at bulk oil operating temperature for oils having a viscosity

2)

index of 160 . 22

1)

Table 10 — ISO Viscosity grade at bulk oil operating temperature for oils having a viscosity

2)

index of 240 . 23

Table 11 — ISO viscosity grade guidelines for enclosed cylindrical worm gear drives . 24

Table 12 — Advantages and disadvantages of various open girth gears lubricants . 25

Table 13 — Minimum Viscosity recommendation for continuous lubrication [mm /s at 40 °C]. 26

Table 14 — Minimum base oil viscosity recommendation for intermittent lubrication [mm /s at

40 °C] . 26

Table 15 — Typical maximum oil flow velocities. 33

Table 16 — Advantages and disadvantages of greases .35

Table 17 — Advantages and disadvantages of oils. 35

Table 18 — Advantages and disadvantages of lubricating compounds. 36

Table 19 — Lubrication system selection based on pitch line velocity . 39

Table 20 — Lubrication system selection based on the type of lubricant. 39

Table 21 — Typical recommended lubricant service . 40

Table 22 — Examples for an on-line oil condition-monitoring system . 40

Table 23 — Sources of metallic elements . 47

Table 24 — What the ISO codes mean. 49

Table 25 — Example of particle size and counts. 49

Table 26 — Characteristics of particles. 51

iv © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies

(ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through ISO

technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical committee has been

established has the right to be represented on that committee. International organizations, governmental and

non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work. ISO collaborates closely with the

International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of electrotechnical standardization.

International Standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

The main task of technical committees is to prepare International Standards. Draft International Standards

adopted by the technical committees are circulated to the member bodies for voting. Publication as an

International Standard requires approval by at least 75 % of the member bodies casting a vote.

In exceptional circumstances, when a technical committee has collected data of a different kind from that

which is normally published as an International Standard (“state of the art”, for example), it may decide by a

simple majority vote of its participating members to publish a Technical Report. A Technical Report is entirely

informative in nature and does not have to be reviewed until the data it provides are considered to be no

longer valid or useful.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of patent

rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

ISO/TR 18792 was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 60, Gears, Subcommittee SC 2, Gear capacity

calculation.

Introduction

Gear lubrication is important in all types of gear applications. Through adequate lubrication, gear design and

selection of gear lubricant, the gear life can be extended and the gearbox efficiency improved. In order to

focus on the available knowledge of gear lubrication, ISO/TC 60 decided to produce this Technical Report

combining primary information about the design and use of lubricants for gearboxes.

vi © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

TECHNICAL REPORT ISO/TR 18792:2008(E)

Lubrication of industrial gear drives

1 Scope

This Technical Report is designed to provide currently available technical information with respect to the

lubrication of industrial gear drives up to pitch line velocities of 30 m/s. It is intended to serve as a general

guideline and source of information about the different types of gear, and lubricants, and their selection for

gearbox design and service conditions. This Technical Report is addressed to gear manufacturers, gearbox

users and gearbox service personnel, inclusive of manufacturers and distributors of lubricants.

This Technical Report is not applicable to gear drives for automotive transmissions.

2 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms, definitions, symbols, indices and units apply.

Table 1 — Symbols, indices and units

Symbol, index Term Unit

A, B, C, D, E points on the path of contact —

b face width mm

C cubic capacity of the oil pump

cm

d diameter mm

d

outside diameter pinion, wheel mm

a1, 2

d

base circle diameter pinion, wheel mm

b1, 2

d

operating pitch diameter pinion, wheel mm

w1, 2

0,5 1,5

f

curvature factor N /mm

H

f

load factor —

L

F

circumferential load at base circle N

bt

n

rotational speed of the oil pump driving shaft rpm

shaft

p pressure bar

p

hertzian stress

N/mm

H

P

gear power kW

P

gear power loss kW

vz

P

total gearbox power loss kW

vzsum

s slip —

t time sec

Table 1 (continued)

Symbol, index Term Unit

V

oil quantity l

Q

oil flow l/min

e

Q

oil flow through the bearings l/min

bearings

Q

oil flow through the gear mesh l/min

gears

Q

oil pump flow l/min

pump

Q

oil flow through the seals l/min

seals

v pitch line velocity m/s

v

surface velocity pinion, wheel m/s

1, 2

v

sliding velocity m/s

g

v

pitch line velocity m/s

t

v

sum velocity m/s

Σ

V

oil tank volume l

tank

z

number of pinion teeth —

β helix angle degree

relation between the calculated film thickness and the

λ —

effective surface roughness

2.1

intermittent lubrication

intermittent common lubrication of gears which are not enclosed

NOTE Gears that are not enclosed are referred to as open gears.

2.2

manual lubrication

hand application

periodical application of lubricant by a user with a brush or spout can

2.3

centralized lubrication

intermittent lubrication of gears by means of a mechanical applicator in a centralized system

2.4

continuous lubrication

continuous application of lubricant to the gear mesh in service

2.5

splash lubrication

bath lubrication

immersion lubrication

dip lubrication

process, in an enclosed system, by which a rotating gear or an idler in mesh with one gear is allowed to dip

into the lubricant and carry it to the mesh

2 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

2.6

oil stream lubrication

pressure-circulating lubrication

forced-circulation lubrication

continuous lubrication of gears and bearings using a pump system which collects the oil in a sump and

recirculates it

2.7

drop lubrication

use of oil pump to siphon the lubricant directly onto the contact portion of the gears via a delivery pipe

2.8

spray lubrication

process in oil stream lubrication by which the oil is pumped under pressure to nozzles that deliver a stream or

spray onto the gear tooth contact, and the excess oil is collected in the sump and then returned to the pump

via a reservoir

2.9

spray lubrication for open gearing

continuous or intermittent application of lubricant using compressed air

2.10

oil mist lubrication

process by which oil mist, formed from the mixing of lubricant with compressed air, is sprayed against the

contact region of the gears

NOTE It is especially suitable for high-speed gearing.

2.11

brush lubrication

process by which lubricant is continuously brushed onto the active tooth flanks of one gear

2.12

transfer lubrication

continuous transferral of lubricant onto the active tooth flanks of a gear by means of a special transfer pinion

immersed in the lubricant or lubricated by a centralized lubrication system

3 Basics of gear lubrication and failure modes

3.1 Tribo-technical parameters of gears

3.1.1 Gear types

There are different types of gear such as cylindrical, bevel and worm. The type of gear used depends on the

application necessary. Cylindrical gears with parallel axes are manufactured as spur and helical gears. They

typically have a line contact and sliding only in profile direction. Cylindrical gears with skewed axes have a

point contact and additional sliding in the axial direction. Bevel gears with an arbitrary angle between their

axes without gear offset have a point contact and sliding in profile direction. They generally have

perpendicular axes and are manufactured as straight, helical or spiral bevel gears. Bevel gears with gear

offset are called hypoid gears with point contact and sliding in profile and axial directions. Worm gears have

crossed axes, line contact and sliding in profile and mainly axial direction.

3.1.2 Load and speed conditions

The main tribological parameters of a gear contact are load, pressure, and rolling and sliding speed. A static

load distribution along the path of contact as shown in Figure 1 can be assumed for spur gears without profile

modification. In the zone of single tooth contact the full load is transmitted by one tooth pair, in the zone of

double tooth contact the load is shared between two tooth pairs in contact.

Key

1 spur gear without profile correction

Figure 1 — Load and speed distribution along the path of contact

The static load distribution along the path of contact can be modified through elasticity and profile

modifications. Due to the vibrational system of the gear contact, dynamic loads occur as a function of the

dynamic and natural frequency of the system. A local Hertzian stress for the unlubricated contact can be

derived from the local load and the local radius of curvature (see Figure 1). When a separating lubricating film

is present, the Hertzian pressure distribution in the contact is modified to an elastohydrodynamic pressure

distribution with an inlet ramp, a region of Hertzian pressure distribution, possibly a pressure spike at the

outlet and a steep decrease from the pressure maximum to the ambient.

The surface speed of the flanks changes continuously along the path of contact (see Figure 1). The sum of

the surface speeds of pinion and wheel represents the hydrodynamically effective sum velocity; half of this

value is known as entraining velocity. The difference of the flank speeds is the sliding velocity, which together

with the frictional force results in a local power loss and contact heating. Rolling without sliding can only be

found in the pitch point with its most favourable lubricating conditions. Unsteady conditions with changing

pressure, sum and sliding velocity along the path of contact are the result. In addition, with each new tooth

coming into contact, the elastohydrodynamic film must be formed anew under often unfavourable conditions of

the scraping edge of the driven tooth (see Figure 2).

4 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Key

1 pinion (driving)

2 wheel (driven)

3 first contact point

Figure 2 — Scraping edge at the ingoing mesh

3.2 Gear lubricants

3.2.1 Overview of lubrication

Regarding gear lubrication, the primary concern is usually the gears. In addition to the gears there are many

other components that must also be served by the fluid in the gearbox. Consideration should also be given to

the bearings, seals, and other ancillary equipment, e.g., pumps and heat exchangers, that can be affected by

the choice of lubricant. In many open gear drives the bearings are lubricated independently of the gears, thus

allowing for special fluid requirements should the need arise. However, most enclosed and semi-enclosed

gear drives utilize a single lubricant and lubricant source of supply for the gears, bearings, seals, pumps, etc.

Therefore, selecting the correct lubricant for a gear drive system includes addressing the lubrication needs of

not only the gears but all other associated components in the system.

A lubricant is used in gear applications to control friction and wear between the intersecting surfaces, and in

enclosed gear drive applications to transfer heat away from the contact area. They also serve as a medium to

carry the additives that can be required for special functions. There are many different lubricants available to

accomplish these tasks. The choice of an appropriate lubricant depends in part on matching its properties to

the particular application. Lubricant properties can be quite varied depending on the source of the base

stock(s), the type of additive(s), and any thickeners that might be used. The base stock and thickener

components generally provide the foundation for the physical properties that define the lubricant, while the

additives provide the chemical properties that are critical for certain performance needs. The overall

performance of the lubricant is dependent on both the physical and chemical properties being in the correct

balance for the application. The following clauses describe the more common types of base stocks, thickeners

and additive chemicals used in gear lubricant formulations today.

3.2.2 Physical properties

The physical properties of a lubricant, such as viscosity and pour point, are largely derived from the base

stock(s) from which they are produced. For example, the crude source, the fraction or cut, and the amount of

refining, such as dewaxing, of a given mineral oil can significantly alter the way it will perform in service. While

viscosity is the most common property associated with a lubricant, there are many other properties that

contribute to the makeup and character of the finished product. The properties of finished gear lubricants are

the result of a combination of base stock selection and additive technology.

3.3 Base fluid components

A key element of the finished fluid is the base oil. The base oil comes from two general sources: mineral; or,

synthetic. The term mineral usually refers to base oils that have been refined from a crude oil source, whereas

synthetics are usually the product of a chemical reaction of one or more selected starting materials. The

finished fluids can also contain mixtures of one or more base oil types. Partial synthetic fluids contain mixtures

of mineral and synthetic base oils. Full synthetic fluids can also be mixtures of two or more synthetic base oils.

As a current example, mixtures of polyalphaolefins (PAO) and esters are commonly used in synthetic

formulations. Mixtures are generally used to tailor the properties of the finished fluid to a specific application or

need. An overview of the general characteristics of different base fluids is shown in Table 2. Additional

information regarding base fluid characteristics is shown in the following sections.

Table 2 — General characteristics of base fluids

Mineral Polyalpha– Poly-alkylene- Phosphate

Characteristic Ester

paraffinic olefins (PAO) glycol (PAG) esters

Viscosity – temperature

relationship (typical viscosity 90 – 130 130 – 150 50 – 140 200 – 240 <100

index)

Specific heat

1,0 1,3 – 1,5 1,1 – 1,3 1,1 – 1,3 1,0 – 1,2

(relative)

Pressure-viscosity at 1 GPa

1,0 0,8 0,5 ~1,0 1,0 – 1,1

(relative)

Comparability solvency with

Excellent Good Excellent Poor Good

mineral fluids

Comparability solvency with PAO

Good Excellent Excellent Poor Good

fluids

Good to

Additive solvency Good Excellent Limited Good

Excellent

3.3.1 Mineral-based fluids

Mineral-based gear oils have been successfully used for several years in many industrial gear drive systems.

Mineral oil lubricants are petroleum-based fluids produced from crude oil through petroleum refining

technology. Paraffinic mineral-based gear oils have viscosity indices (VI) that are commonly lower than most,

but not all synthetic-based gear oils. This usually means that the low temperature properties of these

mineral-based lubricants will not be as good as for a comparable grade synthetic fluid. If low ambient

temperatures are involved with the operation of the equipment, this should be factored into the decision

process. At high temperatures, mineral-based lubricants are more prone to oxidation than synthetics due in

part to the amount of residual polar and unsaturated compounds in the base component. Mineral-based

lubricants will generally provide a higher viscosity under pressure than most synthetics and therefore provide

a thicker film at moderate temperatures. On the other hand, at higher temperatures, usually around 80 °C to

100 °C or more, the higher VI of synthetic fluids generally overcomes the disadvantage of having a lower

pressure-viscosity coefficient. At these higher temperatures, the film thickness can be higher for PAOs

compared to mineral oils. Probably the primary advantages of mineral-based oils over synthetic-based oils are

their lower initial purchase cost and greater availability worldwide. If a mineral oil is preferred, some of the

weaker properties, compared to a synthetic fluid, can be improved through the thickener and additive systems

available today.

6 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

3.3.2 Synthetic-based fluids

Synthetic oils differ from petroleum-based oils in that they are not found in nature, but are manufactured

chemically and have special properties that enhance performance or accommodate severe operating

conditions. Because they are manufactured, many of their properties can be tailored to meet specific needs

through the choice of starting materials and reaction processing. Many synthetic oils are stable at high

operating temperatures, have high VI, i.e. smaller viscosity changes with temperature variations, and low pour

points. This means that equipment filled with most commercially available synthetic gear oils can be started

without difficulty at lower bulk oil temperatures than those using mineral oils. Another key advantage is that

they are inherently more stable at higher temperatures against oxidative degradation than their mineral

counterparts, again owing this advantageous property to the uniformity and composition of the fluid structure.

Each type of synthetic lubricant has unique characteristics and the limitations of each should be understood.

Characteristics such as compatibility with other lubrication systems and mechanical components (seals,

sealants, paints, backstops and clutches), behaviour in the presence of moisture, lubricating qualities and

overall economics should be carefully analysed for each type of synthetic lubricant under consideration for a

given application. In the absence of field experience in similar applications, the use of synthetic oil ought to be

coordinated carefully between the user, the gear manufacturer and the lubricant supplier. Synthetic lubricants

can improve gearbox efficiency and can operate cooler than mineral oils because of their viscosity-

temperature characteristics and structure-influenced heat transfer properties. Decreasing the operating

temperature of a gearbox lubricant is desirable. Lower lubricant temperatures increase the gear and bearing

lives by increasing lubricant film thickness, and increase lubricant life by reducing oxidation.

There are several different types of synthetic base oils available today. Their compositions and properties

result from the different chemicals that are combined in their manufacture. Some of the major types of

synthetic base oils are described in the following clauses. The lubricant supplier is generally consulted for

additional information on synthetics for a given application.

3.3.2.1 Polyalphaolefin-based oils

PAOs, or olefin oligomers, are paraffin-like liquid hydrocarbons which can be synthesized to achieve a unique

combination of high viscosity-temperature characteristic, low volatility, excellent low temperature viscometrics

and thermal stability, and a high degree of oxidation resistance with appropriate additive treatment along with

a structure that can improve equipment efficiency. These characteristics result from the wax-free combination

of moderately branched paraffinic hydrocarbon molecules of predetermined chain length. Compared to

conventional mineral oils, some PAO lubricants have poorer solvency for additives and for sludge that can

form as the oil ages. Lubricant formulators commonly add a higher solvency fluid, such as ester or alkylated

aromatic fluids, in order to keep the additives in solution and to prevent sludge from being deposited on the

gearbox components.

3.3.2.2 Synthetic ester lubricants

Esters are produced from the reaction of an alcohol with an organic acid. There are a wide variety of esters

available that can be produced because of the numerous existing combinations of acids and alcohols. The

principal advantage of many esters is their excellent thermal and oxidative stability. A primary weakness of

some is poor hydrolytic stability. When in contact with water, esters can deteriorate through a reverse reaction

and revert to an alcohol and organic acid. A secondary weakness with some esters is a VI lower than most

paraffinic mineral-based oils. Some esters do, however, provide a VI higher than mineral or PAO lubricants. It

is possible for some ester-based gear oils to be suitable in water protection areas since they can be

biodegradable.

On the negative side, ester-based gear oils or lubricants containing esters can adversely affect filters,

elastomeric seals, adhesives, sealants, paint, and other surface treatments such as layout lacquer used for

contact pattern tests. Therefore, lubricants with esters should be tested for compatibility with all gearbox

components before they are used in service. Another weakness of the ester class of lubricants is their poor

film-forming capabilities. Esters tend to have very low pressure-viscosity coefficients which relate to the ability

of the fluid’s film thickness in the contact region. This could lead to higher wear.

3.3.2.3 Polyalkyleneglycol (PAG) lubricants

PAG-based oils have a chemical structure that is distinctly different from both PAO and ester-based oils.

PAGs are generally made from the reaction product of ethylene oxide and propylene oxide to form a polyether

type structure. The properties of the structure are dependent on the molecular weight and the ratio of ethylene

and propylene oxides used in the reaction mixture. PAG-based gear oils can have excellent thermal and

oxidative stability and most have exceptionally high VI, many of which are greater than 200. However, many

PAGs have poor corrosion properties in the presence of salt water. In standard distilled water corrosion tests,

carefully selected additives can control rust.

The primary difficulties with PAG lubricants are that they can be very hygroscopic (tend to absorb water) and

not very miscible with mineral or other synthetic fluid-type base fluids. The affinity for water and compatibility

with more common fluids is a function of the ethylene oxide to propylene oxide ratio. Special flushing

procedures are required when switching between a PAG and mineral or other synthetic fluid lubricant; the

lubricant supplier is consulted for specific details. A secondary difficulty with PAG lubricants is that they can

require different specifications for paints, seals, sealants, and filters. Also, special handling would be required

for the disposal of PAG-type lubricants.

3.3.2.4 Phosphate esters

While there are many groups of phosphates, it is the trisubstituted, neutral esters of orthophosphoric acid that

have found significant use as synthetic base stocks. The commercially significant derivatives used as

synthetic base stocks are compounds in which all three substituents on the phosphorus molecule are alky,

aryl, or alkyl-aryl moieties containing at least four carbon atoms plus hydrogen and oxygen. They are probably

best known for their inherent fire-resistance and find wide use as fire-resistant industrial hydraulic fluids.

Additionally, they can be used as gear lubricants in the gearboxes of gas and steam turbines.

The trisubstituted phosphate esters, being neutral, have demonstrated chemical stability through many years

of practical industrial service over a wide temperature range. They generally do not react with most organic

compounds and are excellent solvents for most commonly used lubricant additives. In addition, they have

demonstrated excellent thermal and oxidative stability in various laboratory tests. When one thinks of

synthetics, the most common characteristic is excellent viscosity-temperature relationships. This, however, is

not the case for phosphate esters as they typically have viscosity indices (VI) below 100.

Consideration should also be given to phosphate ester-type fluids during service due to their affinity with water.

3.4 Thickeners

Thickeners, also known as viscosity modifiers (VM) or viscosity index improvers (VII), are not common in

industrial gear oil formulations, but are used in some applications. Thickeners are generally polymers, which

cause the oil to thicken to a much greater extent per unit volume of material than a conventional base stock,

such as a bright stock or cylinder stock. At higher temperatures the molecule expands creating a thickening

effect. As the temperature decreases the polymer molecule tends to contract minimizing the thickening effect.

A schematic diagram of this principle is shown in Figure 3. The unique ability of these polymers to expand and

contract as a function of temperature enables the finished blend to have much better viscosity-temperature

characteristics, thus the terms VM and VII.

Polymers are merely a chemical combination of one starting unit, known as a monomer, into many repeating

units. The properties of the polymer are a function of the relative molecular mass (M , the number of repeating

r

units) and the chemical structure of the monomer. Some of the more common polymer types used as viscosity

modifiers include poly-alpha-olefin, poly-isobutylene, poly-alkyl-acrylate and -methacrylate, and olefin

copolymers.

In addition to altering the viscosity-temperature properties of the finished fluid the choice of polymer can also

have an impact on the supporting film in the gear and bearing contact regions. The film formed in the contact

will be a function of the temperature, pressure and velocity of the surfaces that come into contact with each

other. On the negative side, polymers are subject to mechanical and thermal shearing which results in a

temporary and/or permanent loss of viscosity. The rate of loss is directly proportional to the molecular weight

(M) of the polymer, i.e., higher relative molecular mass polymers result in higher viscosity losses (see

r

8 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Figure 3). Different polymer structures can also influence the response to pressure, temperature, and shear

rate. Each of these parameters becomes important in the overall choice of a thickener.

Figure 3 — Schematic diagram of shear effects on thickeners

3.5 Chemical properties of additives

Additives are typically a small (volume-wise), but critical part of the overall formulation. Additive is a broad

term that encompasses many different chemicals, each providing performance or protection against certain

types of damage or distress. These performance areas include, but are not limited to, antiwear (AW), extreme

pressure (EP) or antiscuff, ferrous corrosion, non-ferrous corrosion, demulsibility, oxidation and foam inhibition.

The chemicals impart or control these performance aspects in the application through reaction with the

component surface or in the bulk oil phase. Most gear lubricants use a variety of chemicals in order to satisfy

the many needs of the application. These chemicals must be selected properly not only for the desired

performance function but for compatibility with the other chemicals in the package so that performance is not

degraded.

Most commercial gear lubricants contain additives or chemicals that enable them to meet specific

performance requirements. Typical additives include: rust inhibitor, oxidation inhibitor, defoamant, AW and

antiscuff agents. Many of the chemicals used to form the additive “package” are single function, but some can

provide benefit in multiple areas. For example, certain thiophosphorus compounds while primarily used for AW

can also provide protection against scuffing or function as oxidation inhibitors. As a minimum base, oils are

treated with some type of rust inhibitor and antioxidant; these are commonly known as R&O or circulating oils.

These oils are not intended for applications where boundary lubrication is expected to occur. Blends

containing AW and antiscuff agents are generally referred to as EP oils.

Additives alone, however, do not establish oil quality with respect to oxidation resistance, demulsibility, low

temperature viscomentrics and viscosity index. Lubricant producers do not usually state which compounds are

used to enhance the lubricant quality, but only specify the generic function such as AW, EP agents, or

oxidation inhibitors. Furthermore, producers do not always use the same additive to accomplish a particular

goal. Consequently, it is possible for any two brands selected for the same application not to be chemically

identical. Users should be aware of these differences, which can have significant consequences when mixing

different products. Another important consideration is incompatibility of lubricant types. Some oils, such as

those used in turbine, hydraulic, and gear applications, are naturally acidic. Other oils, such as engine oils and

some automotive driveline fluids, are alkaline. Acidic and alkaline lubricants are incompatible. Oils for similar

applications but produced by different manufacturers can be incompatible owing to the additives used. When

incompatible fluids are mixed, the additives can be consumed due to chemical reactions with one another.

The resulting oil mixture can be deficient of essential additives and therefore unsuitable for the intended

application. When fresh supplies of the oil in use are not available, the lubricant manufacturer should be

consulted for a recommendation of a compatible oil. Whenever oil is added to a system, the oil and equipment

should be checked frequently to ensure that there are no adverse reactions between the new and existing oil.

Specific checks should include bearing temperatures and signs of foaming, rust or corrosion, and deposits.

Certain precautions must be observed with regard to lubricant additives. Some additives are consumed during

use as part of their method of functioning. As these additives are consumed, lubricant performance for the

specific application is reduced and equipment failure can result under continued use. Oil monitoring

programmes should be implemented to periodically test oils and verify that the essential additives have not

been depleted to unacceptable levels.

3.6 Solid lubricants

Solid lubricants have been used in many different ways over the years to provide additional functionality and

performance to the application. They have been used as supplements to liquid lubricants and greases and as

dry film coatings in specialized applications where liquid lubricants or greases could not be used. The solids

can be grouped into a few classes, the most common being lamellar and polymer. Graphite and molybdenum

disulfide (MoS ) are the best known examples of lamellar solids and poly tetra-fluoroethylene (PTFE) or

®1)

Teflon is the most well-known polymer type. When these are applied to the surface they have a very great

effect on the friction of the inte

...

TECHNICAL ISO/TR

REPORT 18792

First edition

2008-12-15

Lubrication of industrial gear drives

Lubrification des entraînements par engrenages industriels

Reference number

©

ISO 2008

PDF disclaimer

This PDF file may contain embedded typefaces. In accordance with Adobe's licensing policy, this file may be printed or viewed but

shall not be edited unless the typefaces which are embedded are licensed to and installed on the computer performing the editing. In

downloading this file, parties accept therein the responsibility of not infringing Adobe's licensing policy. The ISO Central Secretariat

accepts no liability in this area.

Adobe is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated.

Details of the software products used to create this PDF file can be found in the General Info relative to the file; the PDF-creation

parameters were optimized for printing. Every care has been taken to ensure that the file is suitable for use by ISO member bodies. In

the unlikely event that a problem relating to it is found, please inform the Central Secretariat at the address given below.

© ISO 2008

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from either ISO at the address below or

ISO's member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Contents Page

Foreword. v

Introduction . vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Terms and definitions. 1

3 Basics of gear lubrication and failure modes.3

3.1 Tribo-technical parameters of gears. 3

3.2 Gear lubricants. 5

3.3 Base fluid components . 6

3.4 Thickeners . 8

3.5 Chemical properties of additives . 9

3.6 Solid lubricants . 10

3.7 Friction and temperature . 10

3.8 Lubricating regime. 11

3.9 Lubricant influence on gear failure. 11

4 Test methods for lubricants . 15

4.1 Gear tests . 15

4.2 Other functional tests. 16

5 Lubricant viscosity selection . 19

5.1 Guideline for lubricant selection for parallel and bevel gears (not hypoid). 19

5.2 Guideline for lubricant selection for worm gears. 24

5.3 Guideline for lubricant selection for open girth gears. 24

6 Lubrication principles for gear units . 26

6.1 Enclosed gear units. 27

6.2 Open gearing. 34

7 Gearbox service information . 39

7.1 Initial lubricant fill and initial lubricant change period . 39

7.2 Subsequent lubricant change interval. 39

7.3 Recommendations for best practice for lubricant changes. 40

7.4 Used gear lubricant sample analysis. 41

Bibliography . 52

Figures

Figure 1 — Load and speed distribution along the path of contact. 4

Figure 2 — Scraping edge at the ingoing mesh . 5

Figure 3 — Schematic diagram of shear effects on thickeners. 9

Figure 4 — Mechanisms of surface protection for oils with additives. 11

Figure 5 — Examples of gear oil wear test results. 15

Figure 6 — Immersion of gear wheels . 27

Figure 7 — Immersion depth for different inclinations of the gearbox. 29

Figure 8 — Immersion of gear wheels in a multistage gearbox . 30

Figure 9 — Examples of circuit design, combination of filtration and cooling systems . 34

Figure 10 — Immersion lubrication. 37

Figure 11 — Transfer lubrication. 37

Figure 12 — Circulation lubrication . 38

Figure 13 — Automatic spraying lubrication . 38

Tables

Table 1 — Symbols, indices and units. 1

Table 1 (continued) . 2

Table 2 — General characteristics of base fluids. 6

Table 3 — Example of influence factors on wear . 12

Table 4 — Example of influence factors on scuffing load (transmittable torque). 13

Table 5 — Example of influence factors on micropitting (transmittable torque) . 14

Table 6 — Example of influence factors on pitting (transmittable torque) . 14

1)

Table 7 — ISO Viscosity grade at bulk oil operating temperature for oils having a viscosity

2)

index of 90 . 20

1)

Table 8 — ISO Viscosity grade at bulk oil operating temperature for oils having a viscosity

2)

index of 120 . 21

1)

Table 9 — ISO Viscosity grade at bulk oil operating temperature for oils having a viscosity

2)

index of 160 . 22

1)

Table 10 — ISO Viscosity grade at bulk oil operating temperature for oils having a viscosity

2)

index of 240 . 23

Table 11 — ISO viscosity grade guidelines for enclosed cylindrical worm gear drives . 24

Table 12 — Advantages and disadvantages of various open girth gears lubricants . 25

Table 13 — Minimum Viscosity recommendation for continuous lubrication [mm /s at 40 °C]. 26

Table 14 — Minimum base oil viscosity recommendation for intermittent lubrication [mm /s at

40 °C] . 26

Table 15 — Typical maximum oil flow velocities. 33

Table 16 — Advantages and disadvantages of greases .35

Table 17 — Advantages and disadvantages of oils. 35

Table 18 — Advantages and disadvantages of lubricating compounds. 36

Table 19 — Lubrication system selection based on pitch line velocity . 39

Table 20 — Lubrication system selection based on the type of lubricant. 39

Table 21 — Typical recommended lubricant service . 40

Table 22 — Examples for an on-line oil condition-monitoring system . 40

Table 23 — Sources of metallic elements . 47

Table 24 — What the ISO codes mean. 49

Table 25 — Example of particle size and counts. 49

Table 26 — Characteristics of particles. 51

iv © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies

(ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through ISO

technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical committee has been

established has the right to be represented on that committee. International organizations, governmental and

non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work. ISO collaborates closely with the

International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of electrotechnical standardization.

International Standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

The main task of technical committees is to prepare International Standards. Draft International Standards

adopted by the technical committees are circulated to the member bodies for voting. Publication as an

International Standard requires approval by at least 75 % of the member bodies casting a vote.

In exceptional circumstances, when a technical committee has collected data of a different kind from that

which is normally published as an International Standard (“state of the art”, for example), it may decide by a

simple majority vote of its participating members to publish a Technical Report. A Technical Report is entirely

informative in nature and does not have to be reviewed until the data it provides are considered to be no

longer valid or useful.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of patent

rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

ISO/TR 18792 was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 60, Gears, Subcommittee SC 2, Gear capacity

calculation.

Introduction

Gear lubrication is important in all types of gear applications. Through adequate lubrication, gear design and

selection of gear lubricant, the gear life can be extended and the gearbox efficiency improved. In order to

focus on the available knowledge of gear lubrication, ISO/TC 60 decided to produce this Technical Report

combining primary information about the design and use of lubricants for gearboxes.

vi © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

TECHNICAL REPORT ISO/TR 18792:2008(E)

Lubrication of industrial gear drives

1 Scope

This Technical Report is designed to provide currently available technical information with respect to the

lubrication of industrial gear drives up to pitch line velocities of 30 m/s. It is intended to serve as a general

guideline and source of information about the different types of gear, and lubricants, and their selection for

gearbox design and service conditions. This Technical Report is addressed to gear manufacturers, gearbox

users and gearbox service personnel, inclusive of manufacturers and distributors of lubricants.

This Technical Report is not applicable to gear drives for automotive transmissions.

2 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms, definitions, symbols, indices and units apply.

Table 1 — Symbols, indices and units

Symbol, index Term Unit

A, B, C, D, E points on the path of contact —

b face width mm

C cubic capacity of the oil pump

cm

d diameter mm

d

outside diameter pinion, wheel mm

a1, 2

d

base circle diameter pinion, wheel mm

b1, 2

d

operating pitch diameter pinion, wheel mm

w1, 2

0,5 1,5

f

curvature factor N /mm

H

f

load factor —

L

F

circumferential load at base circle N

bt

n

rotational speed of the oil pump driving shaft rpm

shaft

p pressure bar

p

hertzian stress

N/mm

H

P

gear power kW

P

gear power loss kW

vz

P

total gearbox power loss kW

vzsum

s slip —

t time sec

Table 1 (continued)

Symbol, index Term Unit

V

oil quantity l

Q

oil flow l/min

e

Q

oil flow through the bearings l/min

bearings

Q

oil flow through the gear mesh l/min

gears

Q

oil pump flow l/min

pump

Q

oil flow through the seals l/min

seals

v pitch line velocity m/s

v

surface velocity pinion, wheel m/s

1, 2

v

sliding velocity m/s

g

v

pitch line velocity m/s

t

v

sum velocity m/s

Σ

V

oil tank volume l

tank

z

number of pinion teeth —

β helix angle degree

relation between the calculated film thickness and the

λ —

effective surface roughness

2.1

intermittent lubrication

intermittent common lubrication of gears which are not enclosed

NOTE Gears that are not enclosed are referred to as open gears.

2.2

manual lubrication

hand application

periodical application of lubricant by a user with a brush or spout can

2.3

centralized lubrication

intermittent lubrication of gears by means of a mechanical applicator in a centralized system

2.4

continuous lubrication

continuous application of lubricant to the gear mesh in service

2.5

splash lubrication

bath lubrication

immersion lubrication

dip lubrication

process, in an enclosed system, by which a rotating gear or an idler in mesh with one gear is allowed to dip

into the lubricant and carry it to the mesh

2 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

2.6

oil stream lubrication

pressure-circulating lubrication

forced-circulation lubrication

continuous lubrication of gears and bearings using a pump system which collects the oil in a sump and

recirculates it

2.7

drop lubrication

use of oil pump to siphon the lubricant directly onto the contact portion of the gears via a delivery pipe

2.8

spray lubrication

process in oil stream lubrication by which the oil is pumped under pressure to nozzles that deliver a stream or

spray onto the gear tooth contact, and the excess oil is collected in the sump and then returned to the pump

via a reservoir

2.9

spray lubrication for open gearing

continuous or intermittent application of lubricant using compressed air

2.10

oil mist lubrication

process by which oil mist, formed from the mixing of lubricant with compressed air, is sprayed against the

contact region of the gears

NOTE It is especially suitable for high-speed gearing.

2.11

brush lubrication

process by which lubricant is continuously brushed onto the active tooth flanks of one gear

2.12

transfer lubrication

continuous transferral of lubricant onto the active tooth flanks of a gear by means of a special transfer pinion

immersed in the lubricant or lubricated by a centralized lubrication system

3 Basics of gear lubrication and failure modes

3.1 Tribo-technical parameters of gears

3.1.1 Gear types

There are different types of gear such as cylindrical, bevel and worm. The type of gear used depends on the

application necessary. Cylindrical gears with parallel axes are manufactured as spur and helical gears. They

typically have a line contact and sliding only in profile direction. Cylindrical gears with skewed axes have a

point contact and additional sliding in the axial direction. Bevel gears with an arbitrary angle between their

axes without gear offset have a point contact and sliding in profile direction. They generally have

perpendicular axes and are manufactured as straight, helical or spiral bevel gears. Bevel gears with gear

offset are called hypoid gears with point contact and sliding in profile and axial directions. Worm gears have

crossed axes, line contact and sliding in profile and mainly axial direction.

3.1.2 Load and speed conditions

The main tribological parameters of a gear contact are load, pressure, and rolling and sliding speed. A static

load distribution along the path of contact as shown in Figure 1 can be assumed for spur gears without profile

modification. In the zone of single tooth contact the full load is transmitted by one tooth pair, in the zone of

double tooth contact the load is shared between two tooth pairs in contact.

Key

1 spur gear without profile correction

Figure 1 — Load and speed distribution along the path of contact

The static load distribution along the path of contact can be modified through elasticity and profile

modifications. Due to the vibrational system of the gear contact, dynamic loads occur as a function of the

dynamic and natural frequency of the system. A local Hertzian stress for the unlubricated contact can be

derived from the local load and the local radius of curvature (see Figure 1). When a separating lubricating film

is present, the Hertzian pressure distribution in the contact is modified to an elastohydrodynamic pressure

distribution with an inlet ramp, a region of Hertzian pressure distribution, possibly a pressure spike at the

outlet and a steep decrease from the pressure maximum to the ambient.

The surface speed of the flanks changes continuously along the path of contact (see Figure 1). The sum of

the surface speeds of pinion and wheel represents the hydrodynamically effective sum velocity; half of this

value is known as entraining velocity. The difference of the flank speeds is the sliding velocity, which together

with the frictional force results in a local power loss and contact heating. Rolling without sliding can only be

found in the pitch point with its most favourable lubricating conditions. Unsteady conditions with changing

pressure, sum and sliding velocity along the path of contact are the result. In addition, with each new tooth

coming into contact, the elastohydrodynamic film must be formed anew under often unfavourable conditions of

the scraping edge of the driven tooth (see Figure 2).

4 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Key

1 pinion (driving)

2 wheel (driven)

3 first contact point

Figure 2 — Scraping edge at the ingoing mesh

3.2 Gear lubricants

3.2.1 Overview of lubrication

Regarding gear lubrication, the primary concern is usually the gears. In addition to the gears there are many

other components that must also be served by the fluid in the gearbox. Consideration should also be given to

the bearings, seals, and other ancillary equipment, e.g., pumps and heat exchangers, that can be affected by

the choice of lubricant. In many open gear drives the bearings are lubricated independently of the gears, thus

allowing for special fluid requirements should the need arise. However, most enclosed and semi-enclosed

gear drives utilize a single lubricant and lubricant source of supply for the gears, bearings, seals, pumps, etc.

Therefore, selecting the correct lubricant for a gear drive system includes addressing the lubrication needs of

not only the gears but all other associated components in the system.

A lubricant is used in gear applications to control friction and wear between the intersecting surfaces, and in

enclosed gear drive applications to transfer heat away from the contact area. They also serve as a medium to

carry the additives that can be required for special functions. There are many different lubricants available to

accomplish these tasks. The choice of an appropriate lubricant depends in part on matching its properties to

the particular application. Lubricant properties can be quite varied depending on the source of the base

stock(s), the type of additive(s), and any thickeners that might be used. The base stock and thickener

components generally provide the foundation for the physical properties that define the lubricant, while the

additives provide the chemical properties that are critical for certain performance needs. The overall

performance of the lubricant is dependent on both the physical and chemical properties being in the correct

balance for the application. The following clauses describe the more common types of base stocks, thickeners

and additive chemicals used in gear lubricant formulations today.

3.2.2 Physical properties

The physical properties of a lubricant, such as viscosity and pour point, are largely derived from the base

stock(s) from which they are produced. For example, the crude source, the fraction or cut, and the amount of

refining, such as dewaxing, of a given mineral oil can significantly alter the way it will perform in service. While

viscosity is the most common property associated with a lubricant, there are many other properties that

contribute to the makeup and character of the finished product. The properties of finished gear lubricants are

the result of a combination of base stock selection and additive technology.

3.3 Base fluid components

A key element of the finished fluid is the base oil. The base oil comes from two general sources: mineral; or,

synthetic. The term mineral usually refers to base oils that have been refined from a crude oil source, whereas

synthetics are usually the product of a chemical reaction of one or more selected starting materials. The

finished fluids can also contain mixtures of one or more base oil types. Partial synthetic fluids contain mixtures

of mineral and synthetic base oils. Full synthetic fluids can also be mixtures of two or more synthetic base oils.

As a current example, mixtures of polyalphaolefins (PAO) and esters are commonly used in synthetic

formulations. Mixtures are generally used to tailor the properties of the finished fluid to a specific application or

need. An overview of the general characteristics of different base fluids is shown in Table 2. Additional

information regarding base fluid characteristics is shown in the following sections.

Table 2 — General characteristics of base fluids

Mineral Polyalpha– Poly-alkylene- Phosphate

Characteristic Ester

paraffinic olefins (PAO) glycol (PAG) esters

Viscosity – temperature

relationship (typical viscosity 90 – 130 130 – 150 50 – 140 200 – 240 <100

index)

Specific heat

1,0 1,3 – 1,5 1,1 – 1,3 1,1 – 1,3 1,0 – 1,2

(relative)

Pressure-viscosity at 1 GPa

1,0 0,8 0,5 ~1,0 1,0 – 1,1

(relative)

Comparability solvency with

Excellent Good Excellent Poor Good

mineral fluids

Comparability solvency with PAO

Good Excellent Excellent Poor Good

fluids

Good to

Additive solvency Good Excellent Limited Good

Excellent

3.3.1 Mineral-based fluids

Mineral-based gear oils have been successfully used for several years in many industrial gear drive systems.

Mineral oil lubricants are petroleum-based fluids produced from crude oil through petroleum refining

technology. Paraffinic mineral-based gear oils have viscosity indices (VI) that are commonly lower than most,

but not all synthetic-based gear oils. This usually means that the low temperature properties of these

mineral-based lubricants will not be as good as for a comparable grade synthetic fluid. If low ambient

temperatures are involved with the operation of the equipment, this should be factored into the decision

process. At high temperatures, mineral-based lubricants are more prone to oxidation than synthetics due in

part to the amount of residual polar and unsaturated compounds in the base component. Mineral-based

lubricants will generally provide a higher viscosity under pressure than most synthetics and therefore provide

a thicker film at moderate temperatures. On the other hand, at higher temperatures, usually around 80 °C to

100 °C or more, the higher VI of synthetic fluids generally overcomes the disadvantage of having a lower

pressure-viscosity coefficient. At these higher temperatures, the film thickness can be higher for PAOs

compared to mineral oils. Probably the primary advantages of mineral-based oils over synthetic-based oils are

their lower initial purchase cost and greater availability worldwide. If a mineral oil is preferred, some of the

weaker properties, compared to a synthetic fluid, can be improved through the thickener and additive systems

available today.

6 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

3.3.2 Synthetic-based fluids

Synthetic oils differ from petroleum-based oils in that they are not found in nature, but are manufactured

chemically and have special properties that enhance performance or accommodate severe operating

conditions. Because they are manufactured, many of their properties can be tailored to meet specific needs

through the choice of starting materials and reaction processing. Many synthetic oils are stable at high

operating temperatures, have high VI, i.e. smaller viscosity changes with temperature variations, and low pour

points. This means that equipment filled with most commercially available synthetic gear oils can be started

without difficulty at lower bulk oil temperatures than those using mineral oils. Another key advantage is that

they are inherently more stable at higher temperatures against oxidative degradation than their mineral

counterparts, again owing this advantageous property to the uniformity and composition of the fluid structure.

Each type of synthetic lubricant has unique characteristics and the limitations of each should be understood.

Characteristics such as compatibility with other lubrication systems and mechanical components (seals,

sealants, paints, backstops and clutches), behaviour in the presence of moisture, lubricating qualities and

overall economics should be carefully analysed for each type of synthetic lubricant under consideration for a

given application. In the absence of field experience in similar applications, the use of synthetic oil ought to be

coordinated carefully between the user, the gear manufacturer and the lubricant supplier. Synthetic lubricants

can improve gearbox efficiency and can operate cooler than mineral oils because of their viscosity-

temperature characteristics and structure-influenced heat transfer properties. Decreasing the operating

temperature of a gearbox lubricant is desirable. Lower lubricant temperatures increase the gear and bearing

lives by increasing lubricant film thickness, and increase lubricant life by reducing oxidation.

There are several different types of synthetic base oils available today. Their compositions and properties

result from the different chemicals that are combined in their manufacture. Some of the major types of

synthetic base oils are described in the following clauses. The lubricant supplier is generally consulted for

additional information on synthetics for a given application.

3.3.2.1 Polyalphaolefin-based oils

PAOs, or olefin oligomers, are paraffin-like liquid hydrocarbons which can be synthesized to achieve a unique

combination of high viscosity-temperature characteristic, low volatility, excellent low temperature viscometrics

and thermal stability, and a high degree of oxidation resistance with appropriate additive treatment along with

a structure that can improve equipment efficiency. These characteristics result from the wax-free combination

of moderately branched paraffinic hydrocarbon molecules of predetermined chain length. Compared to

conventional mineral oils, some PAO lubricants have poorer solvency for additives and for sludge that can

form as the oil ages. Lubricant formulators commonly add a higher solvency fluid, such as ester or alkylated

aromatic fluids, in order to keep the additives in solution and to prevent sludge from being deposited on the

gearbox components.

3.3.2.2 Synthetic ester lubricants

Esters are produced from the reaction of an alcohol with an organic acid. There are a wide variety of esters

available that can be produced because of the numerous existing combinations of acids and alcohols. The

principal advantage of many esters is their excellent thermal and oxidative stability. A primary weakness of

some is poor hydrolytic stability. When in contact with water, esters can deteriorate through a reverse reaction

and revert to an alcohol and organic acid. A secondary weakness with some esters is a VI lower than most

paraffinic mineral-based oils. Some esters do, however, provide a VI higher than mineral or PAO lubricants. It

is possible for some ester-based gear oils to be suitable in water protection areas since they can be

biodegradable.

On the negative side, ester-based gear oils or lubricants containing esters can adversely affect filters,

elastomeric seals, adhesives, sealants, paint, and other surface treatments such as layout lacquer used for

contact pattern tests. Therefore, lubricants with esters should be tested for compatibility with all gearbox

components before they are used in service. Another weakness of the ester class of lubricants is their poor

film-forming capabilities. Esters tend to have very low pressure-viscosity coefficients which relate to the ability

of the fluid’s film thickness in the contact region. This could lead to higher wear.

3.3.2.3 Polyalkyleneglycol (PAG) lubricants

PAG-based oils have a chemical structure that is distinctly different from both PAO and ester-based oils.

PAGs are generally made from the reaction product of ethylene oxide and propylene oxide to form a polyether

type structure. The properties of the structure are dependent on the molecular weight and the ratio of ethylene

and propylene oxides used in the reaction mixture. PAG-based gear oils can have excellent thermal and

oxidative stability and most have exceptionally high VI, many of which are greater than 200. However, many

PAGs have poor corrosion properties in the presence of salt water. In standard distilled water corrosion tests,

carefully selected additives can control rust.

The primary difficulties with PAG lubricants are that they can be very hygroscopic (tend to absorb water) and

not very miscible with mineral or other synthetic fluid-type base fluids. The affinity for water and compatibility

with more common fluids is a function of the ethylene oxide to propylene oxide ratio. Special flushing

procedures are required when switching between a PAG and mineral or other synthetic fluid lubricant; the

lubricant supplier is consulted for specific details. A secondary difficulty with PAG lubricants is that they can

require different specifications for paints, seals, sealants, and filters. Also, special handling would be required

for the disposal of PAG-type lubricants.

3.3.2.4 Phosphate esters

While there are many groups of phosphates, it is the trisubstituted, neutral esters of orthophosphoric acid that

have found significant use as synthetic base stocks. The commercially significant derivatives used as

synthetic base stocks are compounds in which all three substituents on the phosphorus molecule are alky,

aryl, or alkyl-aryl moieties containing at least four carbon atoms plus hydrogen and oxygen. They are probably

best known for their inherent fire-resistance and find wide use as fire-resistant industrial hydraulic fluids.

Additionally, they can be used as gear lubricants in the gearboxes of gas and steam turbines.

The trisubstituted phosphate esters, being neutral, have demonstrated chemical stability through many years

of practical industrial service over a wide temperature range. They generally do not react with most organic

compounds and are excellent solvents for most commonly used lubricant additives. In addition, they have

demonstrated excellent thermal and oxidative stability in various laboratory tests. When one thinks of

synthetics, the most common characteristic is excellent viscosity-temperature relationships. This, however, is

not the case for phosphate esters as they typically have viscosity indices (VI) below 100.

Consideration should also be given to phosphate ester-type fluids during service due to their affinity with water.

3.4 Thickeners

Thickeners, also known as viscosity modifiers (VM) or viscosity index improvers (VII), are not common in

industrial gear oil formulations, but are used in some applications. Thickeners are generally polymers, which

cause the oil to thicken to a much greater extent per unit volume of material than a conventional base stock,

such as a bright stock or cylinder stock. At higher temperatures the molecule expands creating a thickening

effect. As the temperature decreases the polymer molecule tends to contract minimizing the thickening effect.

A schematic diagram of this principle is shown in Figure 3. The unique ability of these polymers to expand and

contract as a function of temperature enables the finished blend to have much better viscosity-temperature

characteristics, thus the terms VM and VII.

Polymers are merely a chemical combination of one starting unit, known as a monomer, into many repeating

units. The properties of the polymer are a function of the relative molecular mass (M , the number of repeating

r

units) and the chemical structure of the monomer. Some of the more common polymer types used as viscosity

modifiers include poly-alpha-olefin, poly-isobutylene, poly-alkyl-acrylate and -methacrylate, and olefin

copolymers.

In addition to altering the viscosity-temperature properties of the finished fluid the choice of polymer can also

have an impact on the supporting film in the gear and bearing contact regions. The film formed in the contact

will be a function of the temperature, pressure and velocity of the surfaces that come into contact with each

other. On the negative side, polymers are subject to mechanical and thermal shearing which results in a

temporary and/or permanent loss of viscosity. The rate of loss is directly proportional to the molecular weight

(M) of the polymer, i.e., higher relative molecular mass polymers result in higher viscosity losses (see

r

8 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Figure 3). Different polymer structures can also influence the response to pressure, temperature, and shear

rate. Each of these parameters becomes important in the overall choice of a thickener.

Figure 3 — Schematic diagram of shear effects on thickeners

3.5 Chemical properties of additives

Additives are typically a small (volume-wise), but critical part of the overall formulation. Additive is a broad

term that encompasses many different chemicals, each providing performance or protection against certain

types of damage or distress. These performance areas include, but are not limited to, antiwear (AW), extreme

pressure (EP) or antiscuff, ferrous corrosion, non-ferrous corrosion, demulsibility, oxidation and foam inhibition.

The chemicals impart or control these performance aspects in the application through reaction with the

component surface or in the bulk oil phase. Most gear lubricants use a variety of chemicals in order to satisfy

the many needs of the application. These chemicals must be selected properly not only for the desired

performance function but for compatibility with the other chemicals in the package so that performance is not

degraded.

Most commercial gear lubricants contain additives or chemicals that enable them to meet specific

performance requirements. Typical additives include: rust inhibitor, oxidation inhibitor, defoamant, AW and

antiscuff agents. Many of the chemicals used to form the additive “package” are single function, but some can

provide benefit in multiple areas. For example, certain thiophosphorus compounds while primarily used for AW