ISO 23032:2022

(Main)Meteorology — Ground-based remote sensing of wind — Radar wind profiler

Meteorology — Ground-based remote sensing of wind — Radar wind profiler

This document provides guidelines for the design, manufacture, installation, and maintenance of a WPR. It describes the following: — Measurement principle (Clause 5). Scatterers that produce echoes and methods of wind velocity measurement are described. The description of the measurement principle mainly aims at providing the information necessary for describing the guidelines in Clauses 6 to 11. — Guidelines for WPR system (Clause 6). Frequency, hardware, software, and signal processing are described. They are mainly applied in designing and manufacturing the hardware and software of WPR. — Guidelines for system performance (Clause 7). Measurement resolution, range sampling, radar sensitivity evaluation, and measurement accuracy are described. They can be used for estimating the measurement performance of a WPR’s system design and operation. — Guidelines for quality control (QC) in digital signal processing (Clause 8). — Guidelines for measurement products and data format (Clause 9). Measurement products obtained by a WPR and their data levels are defined. Guidelines for data file formats are also described. — Guidelines for installation (Clause 10) and maintenance (Clause 11). This document does not aim at providing a thorough description of the measurement principle, WPR systems, and WPR applications. For further details of these items, users are referred to technical books (e.g. References [1],[2],[3]). WPRs are referred to by various names (e.g. radar wind profiler, wind profiler radar, wind profiling radar, atmospheric radar, or clear-air Doppler radar). Conventional naming for WPRs should be allowed.

Météorologie — Télédétection du vent basée au sol — Profileur de vent radar

Le présent document fournit des lignes directrices pour la conception, la fabrication, l'installation et la maintenance des RPV. Il décrit les points suivants: — principe de mesurage (Article 5). Les diffuseurs produisant les échos et les méthodes de mesure de la vitesse du vent sont décrits. La description du principe de mesurage a pour objet principal de fournir les informations nécessaires à la description des lignes directrices des Articles 6 à 11; — lignes directrices pour le système RPV (Article 6). La fréquence, le matériel, les logiciels et le traitement du signal sont décrits. Ceux-ci sont principalement appliqués dans le cadre de la conception et de la fabrication du matériel et des logiciels du RPV; — lignes directrices pour les performances du système (Article 7). La résolution des mesures, l'échantillonnage en distance, l'évaluation de la sensibilité du radar et la précision des mesures sont décrits. Ceux-ci peuvent être utilisés pour estimer la performance de mesurage de la conception et du fonctionnement d'un système RPV; — lignes directrices de contrôle de la qualité (CQ) dans le traitement numérique du signal (Article 8); — lignes directrices de produits de mesurage et de format de données (Article 9). Les produits de mesurage obtenus par un RPV et leurs niveaux de données sont définis. Les lignes directrices de formats de fichiers de données sont également décrites; — lignes directrices d'installation (Article 10) et de maintenance (Article 11). Le présent document n'a pas pour vocation de donner une description détaillée du principe de mesurage, des systèmes RPV et des applications RPV. Pour de plus amples informations sur ces points, il convient que les utilisateurs consultent les livrets techniques (par exemple,[1],[2],[3]). Les RPV sont appelés par différents noms (par exemple, profileur de vent radar, radar atmosphérique, ou radar Doppler en air clair). Il convient que les noms conventionnels des RPV soient autorisés.

Meteorologija - Daljinsko zaznavanje vetra na tleh - Radar za profiliranje vetra

Ta dokument navaja smernice za zasnovo, proizvodnjo, namestitev in vzdrževanje radarjev za profiliranje vetra (WPR). Opisuje naslednje:

– Načelo merjenja (točka 5). Opisane so enote za razprševanje, ki proizvajajo odmeve in metode za merjenje hitrosti vetra. Opis načela merjenja je predvsem usmerjen k zagotavljanju informacij, ki so potrebne za opisovanje smernic v točkah 6 do 11.

– Smernice za sistem radarjev za profiliranje vetra (točka 6). Opisani so frekvenca, strojna oprema, programska oprema in obdelovanje signalov. Ti elementi so predvsem uporabljeni pri zasnovi in izdelavi strojne in programske opreme radarjev za profiliranje vetra.

– Smernice za zmogljivost sistema (točka 7). Opisani so ločljivost merjenja, razpon vzorčenja, ocena občutljivosti radarja in natančnost merjenja. Te elemente je mogoče uporabiti za ocenjevanje uspešnosti merjenja zasnove in delovanja sistema radarjev za profiliranje vetra.

– Smernice za nadzor kakovosti (QC) pri obdelavi digitalnega signala (točka 8).

– Smernice za rezultate merjenja in obliko zapisa podatkov (točka 9). Opredeljeni so rezultati merjenja, pridobljeni z radarji za profiliranje vetra, in njihove ravni podatkov. Opisane so tudi smernice za oblike zapisa podatkovnih datotek.

– Smernice za namestitev (točka 10) in vzdrževanje (točka 11).

Cilj tega dokumenta ni zagotovitev temeljitega opisa načela merjenja, sistemov radarjev za profiliranje vetra in možnosti uporabe radarjev za profiliranje vetra. Več informacij o tem je uporabnikom na voljo v tehnični dokumentaciji (npr. sklici [1], [2], [3]).

Radarji za profiliranje vetra imajo več imen (npr. radar za profiliranje vetra, radar za določitev profila vetra, atmosferski radar ali Dopplerjev radar). Dovoljeno naj bo konvencionalno poimenovanje radarjev za profiliranje vetra.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 15-Dec-2022

- Technical Committee

- ISO/TC 146/SC 5 - Meteorology

- Drafting Committee

- ISO/TC 146/SC 5/WG 8 - Radar wind profiler

- Current Stage

- 6060 - International Standard published

- Start Date

- 16-Dec-2022

- Due Date

- 06-Nov-2021

- Completion Date

- 16-Dec-2022

Overview

ISO 23032:2022 - "Meteorology - Ground-based remote sensing of wind - Radar wind profiler" provides international guidelines for the design, manufacture, installation, operation and maintenance of radar wind profilers (WPRs). The standard explains the measurement principle for ground‑based Doppler radars that profile wind in the troposphere and boundary layer, and sets out best practices for system hardware, software, performance assessment, quality control, data products and formats, installation and upkeep.

Keywords: ISO 23032:2022, radar wind profiler, WPR, wind profiling radar, ground-based remote sensing, Doppler, meteorology

Key topics and technical requirements

- Measurement principle (Clause 5): Describes spectral echo parameters, scatterer sources (turbulent scattering, partial reflection, precipitation echoes), clutter and radio‑frequency interference; covers methods for wind velocity retrieval (e.g., Doppler beam swinging and spaced‑antenna techniques).

- System guidance (Clause 6): Frequency selection, principal hardware components (antenna, transmitter, receiver), signal processing and observation control units; environmental considerations for deployment.

- System performance (Clause 7): Definitions and guidance on range, volume and time resolution, Nyquist limits, radar sensitivity, measurement range and accuracy for assessing WPR performance.

- Quality control (Clause 8): Recommended QC procedures in digital signal processing to ensure reliable velocity and spectrum products.

- Products and data formats (Clause 9): Definitions of measurement products, processing levels and recommended operational/scientific file formats (WMO BUFR and NetCDF examples are referenced).

- Installation and maintenance (Clauses 10–11): Site selection, licensing, infrastructure, clutter/interference mitigation, operational monitoring, preventive and corrective maintenance, spare‑parts and software management.

- Informative annexes: Practical material including radar equation representation, precipitation reflectivity, data assimilation impacts and real‑world data format examples.

Practical applications

ISO 23032:2022 supports reliable deployment and use of WPRs for:

- Atmospheric monitoring and operational weather forecasting

- High‑resolution boundary‑layer and turbulence profiling for research

- Providing wind observations for numerical weather prediction (NWP) assimilation

- Supporting national meteorological networks and routine operational services

Who should use this standard

- National and regional meteorological agencies and network operators

- WPR system designers, manufacturers and integrators

- Data centers and observation managers responsible for quality control and distribution

- Atmospheric researchers and modelers incorporating profiler data into analyses

Related standards and interoperability

ISO 23032:2022 aligns with meteorological data exchange practices by referencing operational formats (WMO BUFR) and scientific formats (NetCDF). Users should coordinate with radio licensing and electromagnetic spectrum regulations and with WMO guidance when integrating WPRs into operational observing systems.

For procurement, system specification and operational deployment, ISO 23032:2022 is a practical reference to ensure consistent, interoperable and quality‑assured radar wind profiler installations.

Buy Documents

ISO 23032:2022 - Meteorology — Ground-based remote sensing of wind — Radar wind profiler Released:16. 12. 2022

ISO 23032:2022 - Meteorology — Ground-based remote sensing of wind — Radar wind profiler Released:16. 12. 2022

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO 23032:2022 is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Meteorology — Ground-based remote sensing of wind — Radar wind profiler". This standard covers: This document provides guidelines for the design, manufacture, installation, and maintenance of a WPR. It describes the following: — Measurement principle (Clause 5). Scatterers that produce echoes and methods of wind velocity measurement are described. The description of the measurement principle mainly aims at providing the information necessary for describing the guidelines in Clauses 6 to 11. — Guidelines for WPR system (Clause 6). Frequency, hardware, software, and signal processing are described. They are mainly applied in designing and manufacturing the hardware and software of WPR. — Guidelines for system performance (Clause 7). Measurement resolution, range sampling, radar sensitivity evaluation, and measurement accuracy are described. They can be used for estimating the measurement performance of a WPR’s system design and operation. — Guidelines for quality control (QC) in digital signal processing (Clause 8). — Guidelines for measurement products and data format (Clause 9). Measurement products obtained by a WPR and their data levels are defined. Guidelines for data file formats are also described. — Guidelines for installation (Clause 10) and maintenance (Clause 11). This document does not aim at providing a thorough description of the measurement principle, WPR systems, and WPR applications. For further details of these items, users are referred to technical books (e.g. References [1],[2],[3]). WPRs are referred to by various names (e.g. radar wind profiler, wind profiler radar, wind profiling radar, atmospheric radar, or clear-air Doppler radar). Conventional naming for WPRs should be allowed.

This document provides guidelines for the design, manufacture, installation, and maintenance of a WPR. It describes the following: — Measurement principle (Clause 5). Scatterers that produce echoes and methods of wind velocity measurement are described. The description of the measurement principle mainly aims at providing the information necessary for describing the guidelines in Clauses 6 to 11. — Guidelines for WPR system (Clause 6). Frequency, hardware, software, and signal processing are described. They are mainly applied in designing and manufacturing the hardware and software of WPR. — Guidelines for system performance (Clause 7). Measurement resolution, range sampling, radar sensitivity evaluation, and measurement accuracy are described. They can be used for estimating the measurement performance of a WPR’s system design and operation. — Guidelines for quality control (QC) in digital signal processing (Clause 8). — Guidelines for measurement products and data format (Clause 9). Measurement products obtained by a WPR and their data levels are defined. Guidelines for data file formats are also described. — Guidelines for installation (Clause 10) and maintenance (Clause 11). This document does not aim at providing a thorough description of the measurement principle, WPR systems, and WPR applications. For further details of these items, users are referred to technical books (e.g. References [1],[2],[3]). WPRs are referred to by various names (e.g. radar wind profiler, wind profiler radar, wind profiling radar, atmospheric radar, or clear-air Doppler radar). Conventional naming for WPRs should be allowed.

ISO 23032:2022 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 07.060 - Geology. Meteorology. Hydrology. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO 23032:2022 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-julij-2023

Meteorologija - Daljinsko zaznavanje vetra na tleh - Radar za profiliranje vetra

Meteorology - Ground-based remote sensing of wind - Radar wind profiler

Météorologie - Télédétection du vent basée au sol - Profileur de vent

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: ISO 23032:2022

ICS:

07.060 Geologija. Meteorologija. Geology. Meteorology.

Hidrologija Hydrology

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 23032

First edition

2022-12

Meteorology — Ground-based remote

sensing of wind — Radar wind profiler

Météorologie — Télédétection du vent basée au sol — Profileur de

vent radar

Reference number

© ISO 2022

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may

be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on

the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below

or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

CP 401 • Ch. de Blandonnet 8

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva

Phone: +41 22 749 01 11

Email: copyright@iso.org

Website: www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii

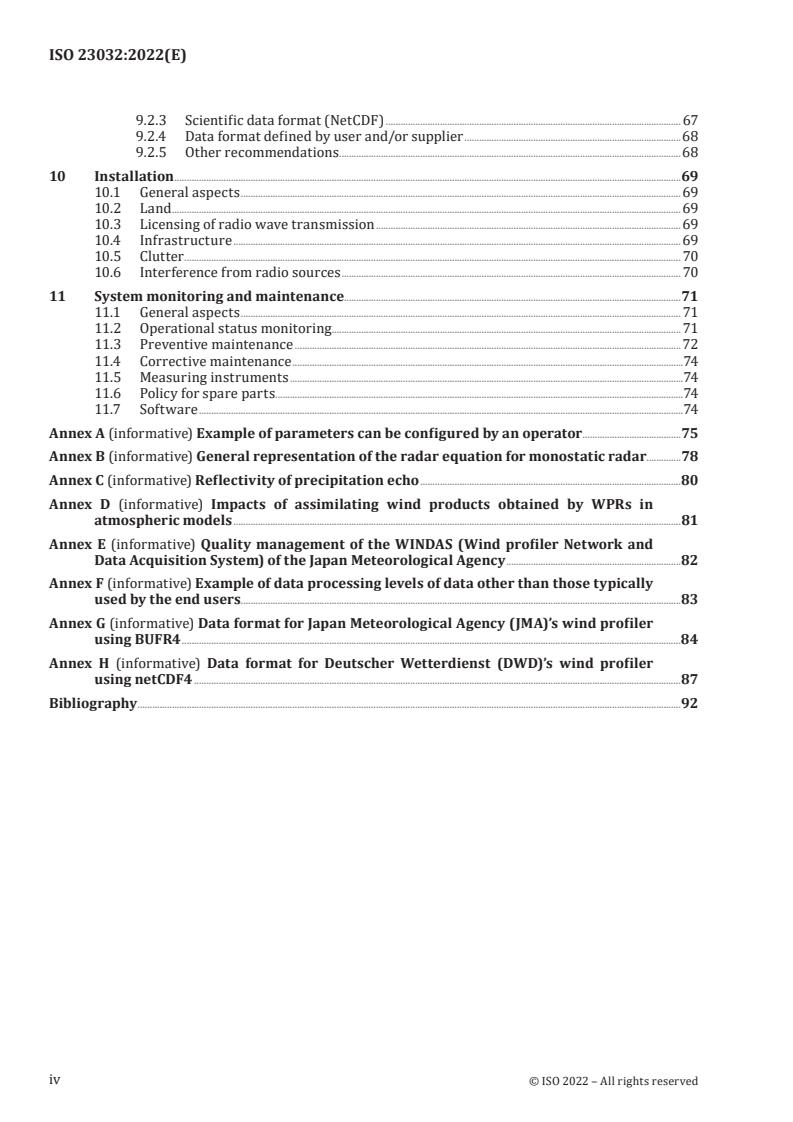

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction . vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Symbols and abbreviated terms.2

4.1 Symbols . 2

4.2 Abbreviated terms . 3

5 Measurement principle . 4

5.1 Spectral parameters of the echo . 4

5.2 Sources of received signals . 7

5.2.1 Turbulent scattering and partial reflection . 7

5.2.2 Echo in precipitation . . 9

5.2.3 Clutter . 9

5.2.4 Interference from radio sources . 10

5.3 Methods of wind velocity measurement . 10

5.3.1 General aspects . 10

5.3.2 Doppler beam swinging (DBS). 10

5.3.3 Spaced antenna (SA) . . 17

6 WPR system .20

6.1 Frequency . 20

6.2 Hardware and software . 21

6.2.1 Principal components . 21

6.2.2 Signal processing . 22

6.2.3 Antenna . 24

6.2.4 Transmitter .29

6.2.5 Receiver .34

6.2.6 Signal processing unit . . 42

6.2.7 Observation control unit . 45

6.2.8 Consideration on environmental conditions . 45

6.3 Resolution enhancement and clutter mitigation using adaptive signal processing .46

6.3.1 Range imaging (frequency domain interferometry) .46

6.3.2 Coherent radar imaging (spatial domain interferometry) . . 51

6.3.3 Adaptive clutter suppression (ACS) .54

7 System performance .57

7.1 Resolution . 57

7.1.1 Range resolution . . 57

7.1.2 Volume resolution .58

7.1.3 Time resolution.58

7.1.4 Nyquist frequency and frequency resolution of Doppler spectrum . 59

7.2 Range sampling . 59

7.3 Radar sensitivity and measurement range .60

7.4 Measurement accuracy .64

7.4.1 Requirements .64

7.4.2 Validation using other means .64

8 Quality control (QC) in digital signal processing .65

9 Products and data format .66

9.1 Products and data processing levels .66

9.2 Data format . 67

9.2.1 General . 67

9.2.2 Operational data format (WMO BUFR) . 67

iii

9.2.3 Scientific data format (NetCDF) . 67

9.2.4 Data format defined by user and/or supplier .68

9.2.5 Other recommendations .68

10 Installation .69

10.1 General aspects . 69

10.2 Land . 69

10.3 Licensing of radio wave transmission . 69

10.4 Infrastructure . 69

10.5 Clutter . 70

10.6 Interference from radio sources . 70

11 System monitoring and maintenance.71

11.1 General aspects . 71

11.2 Operational status monitoring. 71

11.3 Preventive maintenance .72

11.4 Corrective maintenance .74

11.5 Measuring instruments .74

11.6 Policy for spare parts.74

11.7 Software .74

Annex A (informative) Example of parameters can be configured by an operator .75

Annex B (informative) General representation of the radar equation for monostatic radar.78

Annex C (informative) Reflectivity of precipitation echo .80

Annex D (informative) Impacts of assimilating wind products obtained by WPRs in

atmospheric models .81

Annex E (informative) Quality management of the WINDAS (Wind profiler Network and

Data Acquisition System) of the Japan Meteorological Agency .82

Annex F (informative) Example of data processing levels of data other than those typically

used by the end users . .83

Annex G (informative) Data format for Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)’s wind profiler

using BUFR4 .84

Annex H (informative) Data format for Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD)’s wind profiler

using netCDF4 .87

Bibliography .92

iv

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular, the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation of the voluntary nature of standards, the meaning of ISO specific terms and

expressions related to conformity assessment, as well as information about ISO's adherence to

the World Trade Organization (WTO) principles in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT), see

www.iso.org/iso/foreword.html.

This document was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 146, Air quality, Subcommittee SC 5,

Meteorology, and by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) as a common ISO/WMO Standard

under the Agreement on Working Arrangements signed between the WMO and ISO in 2008.

Any feedback or questions on this document should be directed to the user’s national standards body. A

complete listing of these bodies can be found at www.iso.org/members.html.

v

Introduction

Radar wind profiler, also referred to as wind profiler radar, wind profiling radar, atmospheric radar, or

clear-air Doppler radar (hereafter abbreviated to WPR) is an instrument that measures height profiles

of wind velocity in clear air. WPR detects echoes produced by perturbations of the radio refractive

index with a scale half of the radar wavelength (i.e. Bragg scale). The mechanism of radio wave

scattering in clear air was theoretically and experimentally understood in the 1960s. Since the 1970s,

large-sized Doppler radars for observing wind and turbulence in the mesosphere, stratosphere, and

the troposphere (MST radars) have been developed. Owing to their capability of measuring wind and

turbulence with excellent time and height resolution, they have made great contributions to describing

and clarifying the dynamical processes in the atmosphere.

Based on the MST radars, WPRs have been developed mainly since the 1980s. WPRs are designed for

measuring wind velocity predominantly in the troposphere, including the atmospheric boundary layer.

The measurement principle of WPRs are the same used in MST radars but a WPR is frequently smaller

in size than a typical MST radar. WPR can measure wind profiles in both a clear and cloudy atmosphere.

In order to monitor and forecast meteorological phenomena, nationwide operational WPR networks

have been constructed by meteorological agencies. Operational WPRs contribute to improving weather

forecast accuracy through assimilation of their wind products into numerical weather prediction

models used by meteorological agencies. Wind products obtained by operational WPRs are distributed

globally. Further applications of WPRs include the measurement of wind profiles in the vicinity of

airports to enable or improve wind shear warnings. The use of WPRs can improve an airport’s ability

to safely depart and land aircraft. WPRs are also used to analyse or predict the diffusion of pollutants.

In addition, WPRs are widely used by government agencies and various industries, including chemical

plants, mines, and power plants, to control emission levels or for computation of nowcast trajectories

during emergency situations. The high-quality wind products of WPRs are also widely used in

atmospheric research. Therefore, WPRs are an indispensable means for observing wind profiles

continuously in time and height. By additionally using radio acoustic sounding system, WPRs can

measure height profiles of virtual temperature.

In order to attain and retain high quality wind products, WPRs need to be designed, manufactured,

and maintained with state-of-the-art knowledge and ensured measurement capability. Aiming at

ensuring measurement capability of WPRs, this document provides guidelines in design, manufacture,

installation, and maintenance of WPRs.

vi

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 23032:2022(E)

Meteorology — Ground-based remote sensing of wind —

Radar wind profiler

1 Scope

This document provides guidelines for the design, manufacture, installation, and maintenance of a

WPR. It describes the following:

— Measurement principle (Clause 5). Scatterers that produce echoes and methods of wind velocity

measurement are described. The description of the measurement principle mainly aims at providing

the information necessary for describing the guidelines in Clauses 6 to 11.

— Guidelines for WPR system (Clause 6). Frequency, hardware, software, and signal processing are

described. They are mainly applied in designing and manufacturing the hardware and software of

WPR.

— Guidelines for system performance (Clause 7). Measurement resolution, range sampling, radar

sensitivity evaluation, and measurement accuracy are described. They can be used for estimating

the measurement performance of a WPR’s system design and operation.

— Guidelines for quality control (QC) in digital signal processing (Clause 8).

— Guidelines for measurement products and data format (Clause 9). Measurement products obtained

by a WPR and their data levels are defined. Guidelines for data file formats are also described.

— Guidelines for installation (Clause 10) and maintenance (Clause 11).

This document does not aim at providing a thorough description of the measurement principle, WPR

systems, and WPR applications. For further details of these items, users are referred to technical books

(e.g. References [1],[2],[3]).

WPRs are referred to by various names (e.g. radar wind profiler, wind profiler radar, wind profiling

radar, atmospheric radar, or clear-air Doppler radar). Conventional naming for WPRs should be allowed.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references in this document.

3 Terms and definitions

No terms and definitions are listed in this document.

ISO and IEC maintain terminology databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at https:// www .iso .org/ obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at https:// www .electropedia .org/

4 Symbols and abbreviated terms

4.1 Symbols

8 −1

c speed of light (≈ 3,0 × 10 m s )

refractive index structure constant

C

n

Nyquist frequency

f

Nyq

mean Doppler frequency shift of the echo

f

r

antenna gain in decibels

G

ant

loss factor caused by the pulse shaping

L

p

n

radio refractive index

number of antenna beam directions

N

beam

N number of coherent integrations. In this document, N is defined as the

coh coh

number excluding N

pseq

N number of elements in I and Q (I/Q) time series after coherent integrations.

data

N is also the number of elements in the Doppler spectrum

data

number of transmitted frequencies

N

freq

number of incoherent integrations

N

incoh

number of pulse sequences

N

pseq

number of sub-pulses used in phase-modulated pulse compression

N

subp

inter pulse period

T

IPP

echo power

P

echo

noise power of the receiver

P

N

noise power of the Doppler spectrum

P

n

noise power of the Doppler spectrum per Doppler velocity bin

p

n

peak output power of the transmitter

P

p

peak output power at the antenna

P

t

u

zonal wind velocity

v

meridional wind velocity

peak-to-peak voltage

V

pp

radial Doppler velocity

V

r

sample volume

V

s

V wind vector

wind

w

vertical wind velocity

Δr range resolution

η

volume reflectivity

λ radar wavelength

spectral width defined as the half-power full width

σ

3dB

spectral width defined as the standard deviation

σ

std

time width between the two 3-dB drop-off points from the peak point

τ

3dB

duration during which the transmission signal is generated

τ

d

transmitted pulse width

τ

p

H Hermitian operator (complex transposition)

T

superscript which indicates matrix transposition

*

complex conjugation

4.2 Abbreviated terms

ACS adaptive clutter suppression

A/D analog-to-digital

ADC A/D converter

BUFR binary universal form for the representation of meteorological data

COHO coherent oscillator

CRI coherent radar imaging

D/A digital-to-analog

DBS Doppler beam swinging

DCMP directionally constrained minimization of power

DSP digital signal processor

FCA full correlation analysis

FDI frequency domain interferometry

FMCW frequency modulated continuous wave

I/O input/output

I/Q in-phase (I)/quadrature-phase (Q)

IF intermediate frequency

FPGA field programmable gate array

IPP inter pulse period

ITU International Telecommunication Union

JMA Japan Meteorological Agency

LNA low noise amplifier

MTBF mean time between failures

MTTF mean time to failure

NC-DCMP norm-constrained DCMP

NF noise figure

QC quality control

RF radio frequency

RIM range imaging

RL antenna return loss

SA spaced antenna

SNR signal to noise ratio

STALO stable (stabilized) local oscillator

UHF ultra high frequency

UPS uninterruptible power supply

VHF very high frequency

VAD velocity azimuth display

VSWR voltage standing wave ratio

WMO World Meteorological Organization

WPR radar wind profiler, wind profiler radar, wind profiling radar, atmospheric radar,

or clear-air Doppler radar

5 Measurement principle

5.1 Spectral parameters of the echo

The properties of all WPR echoes are generally estimated from the properties of the Doppler spectrum.

Spectral analysis is typically applied to estimate a finite set of parameters such as signal to noise ratio

(SNR), Doppler shift and spectral (spectrum) width. Of particular importance for a WPR is the echo

generated by clear air scattering (clear-air echo). For details of the clear-air echo, see 5.2.1.

NOTE 1 For real-time signal processing to obtain the Doppler spectrum, see 6.2.2 and 6.2.6.

NOTE 2 Interchangeable with spectral width, spectrum width, is also frequently used. The two terms have

the same meaning.

The frequency distribution of the echo contains information on the radial Doppler velocity (V ) and on

r

the wind variance caused by turbulence. Figure 1 shows an example of the Doppler spectrum. The

Doppler spectrum of the echo ( S ) and the noise shown in Figure 1 were produced by a numerical

echo

simulation. In the numerical simulation, Doppler spectra composed of S and white noise were

echo

produced. The noise power of the Doppler spectrum is expressed by P . It is assumed that S follows

n echo

.

a Gaussian distribution and that each spectrum point of S follows the χ distribution with 2

echo

degrees of freedom. The frequency bandwidth of the Doppler spectrum is expressed by B . Produced

s

Doppler spectra were integrated, and the Doppler spectrum after the integration (i.e. incoherent

integration) is plotted. Therefore, the noise variance over B is smaller than the square of the noise

s

power per Doppler velocity bin (p ). The noise variance is one of the principal factors that determine

n

the sensitivity of a WPR receiver. See 6.2.2 and 7.3 for details of incoherent integration and radar

sensitivity, respectively.

In general, it is assumed that S follows a Gaussian distribution. This assumption is generally applied

echo

for the clear-air echo. In this assumption, only the zeroth, first, and second order moments of the echo

are taken into account when determining the spectral parameters. This assumption shall be carefully

discriminated from the assumption that the received signal is the realization of one or more Gaussian

stochastic processes, which include those in both radio wave scattering and of course, uncorrelated

(white) noise. In the event of deviations from this assumption, higher order moments may be considered.

The noise produced in the receiver (receiver noise) can generally be regarded as white noise. For details

of the receiver noise, see 6.2.5.4.

Key

X Doppler velocity

Y intensity

NOTE

— For the definition of the symbols which are not listed in the keys, see text.

— The thin solid curve is an example of a Doppler spectrum which contains the Doppler spectrum of S and

echo

the white noise. The thick solid curve is the sum of P and the idealized S which follows a Gaussian

n echo

distribution and does not have perturbation. The idealized S and P are darkly and lightly shaded,

echo n

respectively. The power of the idealized S is denoted by P . f , σ , σ , and the peak intensity of

echo echo r std 3dB

the idealized S ( p ) is indicated by arrows.

echo k

Figure 1 — Example of Doppler spectrum and spectral parameters

Echo power ( P ), V , and the spectral width are the principal parameters that characterizes the

echo r

echo. They are referred to as the spectral parameters. V is computed from the mean Doppler frequency

r

shift of the echo ( f ). P and f are also the zeroth and first order moment of S , respectively.

r echo r echo

The spectral width defined as the standard deviation (σ ) is the square root of the second order

std

moment of S (see Figure 1). P , f , and σ are expressed by Formula (1), (2) and (3):

echo echo r std

PS= ()fdf (1)

echo echo

∫

fS ()fdf

echo

∫

f = (2)

r

Sf df

()

echo

∫

ff− Sf df

() ()

recho

∫

σ = (3)

std

Sf()df

echo

∫

where f is the Doppler frequency.

The relation between f and V is expressed by Formula (4):

r r

λ

Vf≈− (4)

rr

In Formula (4), V is defined to be positive when its direction is away from the antenna. However, when

r

one prefers to use the sign definition of V as that of f , V can be defined to be positive when its

r r r

direction is toward the antenna. In any case, the direction of V shall be defined clearly in the design

r

and manufacture of the WPR in order to prevent possible mistakes in the design, manufacture,

operation, and maintenance of the WPR. In this document, V is defined to be positive when its direction

r

is away from the antenna.

The spectral width can be also defined as the half-power full width (σ ) or half-power half width of

3dB

σ

3dB

the echo (i.e. ). When S is assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution, σ can be calculated

echo 3dB

by the relation of Formula (5):

σσ= 22ln2 (5)

3dB std

Because the spectral width can be expressed under the above-mentioned definitions, the definition

of the spectral width shall be given explicitly. It shall be noted that the spectral width is not only

determined by wind perturbation caused by turbulence, but also contains broadening effects due to the

[4]

angular and vertical extension of the sample volume . Details of the sample volume are described in

7.1.2.

In the estimation of the spectral parameters, P is also estimated. SNR is expressed by Formula (6):

n

P

echo

SNR= (6)

P

n

In the digital signal processing for estimating the spectral parameters and P , the noise power per

n

Doppler velocity bin ( p ) is generally used. p is expressed by Formula (7):

n n

Δf

pP= (7)

nn

B

s

where Δf is the frequency resolution of the Doppler spectrum (i.e. interval of the Doppler frequency

bins). It is noted that interference from other radio sources that contaminates the received signal has

frequency dependency in general. Therefore, contamination due to the radio interference can produce a

frequency dependency of the noise. Details of the interference from radio sources are described in 5.2.4

and 10.6.

When it is assumed that S follows a Gaussian distribution and SNR is infinite, the estimation error

echo

of Doppler velocity or the spectral width, ε , can be estimated by Formula (8):

v

σ

2

v

ε =K (8)

vv

T

c

where

K is the coefficient;

v

-1

σ is the spectral width defined as the standard deviation in m s ;

v

T is the measurement period in s.

c

When the antenna beam direction is changed after collecting a Doppler spectrum (i.e. after

NN N times transmissions and receptions) or after collecting all of the Doppler spectra used

pseq cohdata

in incoherent integration (i.e. after NN NN times transmissions and receptions),

pseq cohdataincoh

TT= NN NN . When the antenna beam direction is changed on a pulse-to-pulse basis,

cIPP pseq cohdataincoh

TT= NN NN N . See 6.2.3.2.5 for details about the timing change of the antenna

cIPP beam pseq cohdataincoh

beam direction.

K is defined by Formula (9):

v

λ

2

Kk= (9)

verr

2

where

k is the coefficient;

err

λ

is the radar wavelength;

Formulae (8) and (9) are derived from Formulae (13) and (14) in Reference [5], respectively. The value

of k (see Reference [5]) is listed in Table 1.

err

Table 1 — Value of k

err

Parameter Least square method Moment method

Doppler velocity 0,63 0,38

Spectral width 0,60 0,24

Error estimations of the spectral parameters when considering SNR is described in 6.3, 6.4, and 6.5 of

Reference [2].

5.2 Sources of received signals

5.2.1 Turbulent scattering and partial reflection

The ability to detect the clear-air echo is the most important characteristic of a WPR. It makes a WPR

capable of determining vertically resolved profiles of the wind vector from the measured Doppler shift

of the clear-air echo. There are two major mechanisms that produce echoes in clear air: turbulent

scattering from atmospheric turbulence and partial reflection from the horizontally stratified

atmosphere. Partial reflection is also referred to as Fresnel scattering. Atmospheric turbulence

produces perturbation of n , and perturbations of n with the scale of half of λ (i.e. Bragg scale) is a

source of radio wave scattering in clear air.

NOTE The clear-air echo is a return from a radio wave scattering caused by variations of the radio refractive

index n , and does not include scatterings from hard targets in the air (e.g. hydrometeors, insects, birds, and

aircrafts).

n in the neutral (i.e. unionized) atmosphere is given by Formula (10):

p e

−−51

n=+17,,76×+10 3731× 0 (10)

T

T

where

p

is the atmosphere pressure in hPa;

T

is the atmospheric temperature in K;

e

is the partial pressure of water vapour in hPa.

When perturbations of n is isotropic, turbulent scattering is also isotropic.

The refractive index structure constant C is defined as in Formula (11):

n

2 23/

nr+δδrn− rC= r (11)

[]() ()

n

where r is an arbitrary position and δr is a small distance between two spaced locations, respectively.

Because T and e are perturbed by turbulence and n depends on them, C significantly varies due to

n

the atmospheric conditions that determine T and e [see Formula (10)].

The frequency of a WPR is generally selected so that turbulent scattering occurs in the inertial sub-

range of turbulence. Frequencies between 50 MHz and 3 GHz have generally been used for WPRs.

In the inertial sub-range, the energy cascades from the largest eddies to the smallest ones through an

inertial (and inviscid) mechanism. The inertial sub-range exists between the inner scale of turbulence

( l ) and the buoyancy length scale (L ). l is the scale for determining the transition region between

0 B 0

the viscous and inertial sub-ranges, and L is the scale for determining the transition region between

B

the inertial and buoyancy sub-ranges. In the buoyancy sub-range, the turbulent eddies become

flattened and anisotropic. In the viscous sub-range, the smallest eddy is strongly affected by viscosity,

and kinetic energy is converted into heat. The transition from the inertial range to the viscous range

explains the reason why the maximum attainable height coverage for WPRs decreases towards smaller

wavelengths. Viscous subrange is also referred to as dissipative subrange. Long wavelengths (i.e. low

frequencies) whose Bragg scale lie in buoyance sub-range and short wavelengths (i.e. high frequencies)

whose Braggscale lie in the viscous sub-range are not preferable from the viewpoint of radar

sensitivity. See 3.4.2 and 7.3.3 of Reference [1] for more details of the inertial sub-range.

Horizontally stratified layers having sharp vertical gradients of n are known to produce partial

reflection. The echo intensity from partial reflection shows a strong dependency on the zenith angle.

Near zenith it reaches a maximum and decreases rapidly as the zenith angle increases.

The partial reflection coefficient ρ is given by Formula (12):

+l/2

1 1dn

2 − jzκ

ρ = edz (12)

∫

−l/2

4 ndz

where

l

is the thickness of the stratified layer;

z

is the altitude;

κ

is the wave number given as κ =4πλ/ .

See 3.4.3 of Reference [1] for more details of partial reflection. Partial reflection is not observed at the

[1]

UHF and microwave bands .

The intensity of the clear-air echo is determined by the strength of n perturbation caused by turbulence

or by the strength of vertical gradient of n caused by horizontally stratified layers.

5.2.2 Echo in precipitation

Raindrops, hail, snow crystals, ice crystals, and mixed-phase particles in precipitation (precipitation

echo) are also sources of echoes. The intensity of the precipitation echo is frequently comparable to

that of the clear-air echo for the VHF band and is generally greater than that of the clear-air echo for the

UHF band.

If both the precipitation echo and the clear-air echo exist in the Doppler spectrum, the measured

Doppler velocity can be a combination of wind (velocity of clear air) and terminal velocity of

hydrometeors relative to the ground. In this case, the vertical wind cannot be estimated correctly when

both scattering contributions cannot be separated. Nevertheless, the horizontal wind can usually be

derived accurately since the horizontal displacement velocity of the rather small hydrometeors is a

good proxy for the horizontal wind. WPRs using the UHF band generally measure the horizontal wind

velocity at a greater height in precipitation than in clear air.

5.2.3 Clutter

Undesired echoes are referred to as clutter. Because clutter contaminates the Doppler spectrum, it can

significantly decrease the quality of measurement products obtained by the WPR.

The sources of clutter are as follows:

— Clutter from sources fixed on the ground, referred to as ground clutter: Land, grass, trees on hills

and mountains, and high metallic structures (e.g. towers, buildings, and power lines) are the major

sources of ground clutter. Ground clutter can be distributed over a wide area. Though the mean

Doppler frequency of ground clutter is zero, the oscillation of clutter source can broaden the Doppler

spectrum of the ground clutter. Especially when the source of ground clutter is oscillatory (e.g.

grass, trees or power lines), the ground clutter peak in the Doppler spectrum can be significantly

broadened by a strong surface wind.

— Clutter from rotating objects: Wind turbines and rotating antennas are the major sources. Clutter

from them significantly spreads over a wide frequency range of the received Doppler spectrum.

— Clutter from the sea surface, referred to as sea clutter: Because sea clutter is distributed over a wide

area, it generally spreads over the received Doppler spectrum both in range and in frequency. The

intensity and Doppler spreading of sea clutter is a function of the surface wind.

— Clutter from moving sources on the ground or sea: Vehicles, trains, and ships are the major sources.

Clutter from vehicles frequently spreads over a wide frequency range of the Doppler spectrum

because road traffic flows in two opposite directions. The location and Doppler velocity of clutter

from trains can rapidly vary with time. Clutter from ships overlaps with sea clutter.

— Clutter from flying objects: Aircraft (e.g. airplanes and helicopters), birds, bats, and insects are the

major sources, and their flying velocity varies with time. Clutter from an aircraft can significantly

spread over the received Doppler spectrum due to its large Doppler velocity and intensity. Clutter

from helicopters can also spread over a wide frequency of the received Doppler spectrum because

of the high speed of their rotating blades. Birds are also a significant clutter source. Migratory

birds can fly at altitudes up to several thousand meters, and they typically fly at night. Intense bird

migration episodes can be a significant problem for WPR measurements if this type of clutter is not

properly addressed in signal processing. Even then, it can lead to gaps in the wind data. Insects in

the air can also be a source of clutter.

Clutter should be carefully taken into account in the design, installation, and digital signal processing.

The clutter environment should be examined in the survey of the installation site (see 10.5). A fence

designed to attenuate radio waves within the frequency band of the WPR (hereafter referred to as

the clutter fence) is a means for mitigating clutter and interference. For details of the clutter fence,

see 6.2.3.4 and 10.5.

QC in digital signal processing is also a means for mitigating clutter (see Clause 8). Adaptive clutter

suppression (ACS), which uses subarray antennas, is a technique that adaptively mitigates clutter by

controlling the side lobe of the receiver antenna. ACS is described in 6.3.3.

In the VHF band, meteors in the upper mesosphere and electromagnetic irregularities in the sporadic

E layer can also be a source of clutter when range aliasing occurs. Range aliasing can be prevented by

selecting the inter pulse period (IPP) sufficiently large to assure that the maximum measurable range

is greater than the heights where the meteors and electromagnetic irregularities can exist. However,

it is noted that preventing range aliasing can cause the loss of radar sensitivity by decreasing the duty

ratio of the transmission. Lightning can also be a source of clutter.

5.2.4 Interference from radio sources

When a radio wave from a man-ma

...

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 23032

First edition

2022-12

Meteorology — Ground-based remote

sensing of wind — Radar wind profiler

Météorologie — Télédétection du vent basée au sol — Profileur de

vent radar

Reference number

© ISO 2022

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may

be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on

the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below

or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

CP 401 • Ch. de Blandonnet 8

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva

Phone: +41 22 749 01 11

Email: copyright@iso.org

Website: www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction . vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Symbols and abbreviated terms.2

4.1 Symbols . 2

4.2 Abbreviated terms . 3

5 Measurement principle . 4

5.1 Spectral parameters of the echo . 4

5.2 Sources of received signals . 7

5.2.1 Turbulent scattering and partial reflection . 7

5.2.2 Echo in precipitation . . 9

5.2.3 Clutter . 9

5.2.4 Interference from radio sources . 10

5.3 Methods of wind velocity measurement . 10

5.3.1 General aspects . 10

5.3.2 Doppler beam swinging (DBS). 10

5.3.3 Spaced antenna (SA) . . 17

6 WPR system .20

6.1 Frequency . 20

6.2 Hardware and software . 21

6.2.1 Principal components . 21

6.2.2 Signal processing . 22

6.2.3 Antenna . 24

6.2.4 Transmitter .29

6.2.5 Receiver .34

6.2.6 Signal processing unit . . 42

6.2.7 Observation control unit . 45

6.2.8 Consideration on environmental conditions . 45

6.3 Resolution enhancement and clutter mitigation using adaptive signal processing .46

6.3.1 Range imaging (frequency domain interferometry) .46

6.3.2 Coherent radar imaging (spatial domain interferometry) . . 51

6.3.3 Adaptive clutter suppression (ACS) .54

7 System performance .57

7.1 Resolution . 57

7.1.1 Range resolution . . 57

7.1.2 Volume resolution .58

7.1.3 Time resolution.58

7.1.4 Nyquist frequency and frequency resolution of Doppler spectrum . 59

7.2 Range sampling . 59

7.3 Radar sensitivity and measurement range .60

7.4 Measurement accuracy .64

7.4.1 Requirements .64

7.4.2 Validation using other means .64

8 Quality control (QC) in digital signal processing .65

9 Products and data format .66

9.1 Products and data processing levels .66

9.2 Data format . 67

9.2.1 General . 67

9.2.2 Operational data format (WMO BUFR) . 67

iii

9.2.3 Scientific data format (NetCDF) . 67

9.2.4 Data format defined by user and/or supplier .68

9.2.5 Other recommendations .68

10 Installation .69

10.1 General aspects . 69

10.2 Land . 69

10.3 Licensing of radio wave transmission . 69

10.4 Infrastructure . 69

10.5 Clutter . 70

10.6 Interference from radio sources . 70

11 System monitoring and maintenance.71

11.1 General aspects . 71

11.2 Operational status monitoring. 71

11.3 Preventive maintenance .72

11.4 Corrective maintenance .74

11.5 Measuring instruments .74

11.6 Policy for spare parts.74

11.7 Software .74

Annex A (informative) Example of parameters can be configured by an operator .75

Annex B (informative) General representation of the radar equation for monostatic radar.78

Annex C (informative) Reflectivity of precipitation echo .80

Annex D (informative) Impacts of assimilating wind products obtained by WPRs in

atmospheric models .81

Annex E (informative) Quality management of the WINDAS (Wind profiler Network and

Data Acquisition System) of the Japan Meteorological Agency .82

Annex F (informative) Example of data processing levels of data other than those typically

used by the end users . .83

Annex G (informative) Data format for Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)’s wind profiler

using BUFR4 .84

Annex H (informative) Data format for Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD)’s wind profiler

using netCDF4 .87

Bibliography .92

iv

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular, the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation of the voluntary nature of standards, the meaning of ISO specific terms and

expressions related to conformity assessment, as well as information about ISO's adherence to

the World Trade Organization (WTO) principles in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT), see

www.iso.org/iso/foreword.html.

This document was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 146, Air quality, Subcommittee SC 5,

Meteorology, and by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) as a common ISO/WMO Standard

under the Agreement on Working Arrangements signed between the WMO and ISO in 2008.

Any feedback or questions on this document should be directed to the user’s national standards body. A

complete listing of these bodies can be found at www.iso.org/members.html.

v

Introduction

Radar wind profiler, also referred to as wind profiler radar, wind profiling radar, atmospheric radar, or

clear-air Doppler radar (hereafter abbreviated to WPR) is an instrument that measures height profiles

of wind velocity in clear air. WPR detects echoes produced by perturbations of the radio refractive

index with a scale half of the radar wavelength (i.e. Bragg scale). The mechanism of radio wave

scattering in clear air was theoretically and experimentally understood in the 1960s. Since the 1970s,

large-sized Doppler radars for observing wind and turbulence in the mesosphere, stratosphere, and

the troposphere (MST radars) have been developed. Owing to their capability of measuring wind and

turbulence with excellent time and height resolution, they have made great contributions to describing

and clarifying the dynamical processes in the atmosphere.

Based on the MST radars, WPRs have been developed mainly since the 1980s. WPRs are designed for

measuring wind velocity predominantly in the troposphere, including the atmospheric boundary layer.

The measurement principle of WPRs are the same used in MST radars but a WPR is frequently smaller

in size than a typical MST radar. WPR can measure wind profiles in both a clear and cloudy atmosphere.

In order to monitor and forecast meteorological phenomena, nationwide operational WPR networks

have been constructed by meteorological agencies. Operational WPRs contribute to improving weather

forecast accuracy through assimilation of their wind products into numerical weather prediction

models used by meteorological agencies. Wind products obtained by operational WPRs are distributed

globally. Further applications of WPRs include the measurement of wind profiles in the vicinity of

airports to enable or improve wind shear warnings. The use of WPRs can improve an airport’s ability

to safely depart and land aircraft. WPRs are also used to analyse or predict the diffusion of pollutants.

In addition, WPRs are widely used by government agencies and various industries, including chemical

plants, mines, and power plants, to control emission levels or for computation of nowcast trajectories

during emergency situations. The high-quality wind products of WPRs are also widely used in

atmospheric research. Therefore, WPRs are an indispensable means for observing wind profiles

continuously in time and height. By additionally using radio acoustic sounding system, WPRs can

measure height profiles of virtual temperature.

In order to attain and retain high quality wind products, WPRs need to be designed, manufactured,

and maintained with state-of-the-art knowledge and ensured measurement capability. Aiming at

ensuring measurement capability of WPRs, this document provides guidelines in design, manufacture,

installation, and maintenance of WPRs.

vi

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 23032:2022(E)

Meteorology — Ground-based remote sensing of wind —

Radar wind profiler

1 Scope

This document provides guidelines for the design, manufacture, installation, and maintenance of a

WPR. It describes the following:

— Measurement principle (Clause 5). Scatterers that produce echoes and methods of wind velocity

measurement are described. The description of the measurement principle mainly aims at providing

the information necessary for describing the guidelines in Clauses 6 to 11.

— Guidelines for WPR system (Clause 6). Frequency, hardware, software, and signal processing are

described. They are mainly applied in designing and manufacturing the hardware and software of

WPR.

— Guidelines for system performance (Clause 7). Measurement resolution, range sampling, radar

sensitivity evaluation, and measurement accuracy are described. They can be used for estimating

the measurement performance of a WPR’s system design and operation.

— Guidelines for quality control (QC) in digital signal processing (Clause 8).

— Guidelines for measurement products and data format (Clause 9). Measurement products obtained

by a WPR and their data levels are defined. Guidelines for data file formats are also described.

— Guidelines for installation (Clause 10) and maintenance (Clause 11).

This document does not aim at providing a thorough description of the measurement principle, WPR

systems, and WPR applications. For further details of these items, users are referred to technical books

(e.g. References [1],[2],[3]).

WPRs are referred to by various names (e.g. radar wind profiler, wind profiler radar, wind profiling

radar, atmospheric radar, or clear-air Doppler radar). Conventional naming for WPRs should be allowed.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references in this document.

3 Terms and definitions

No terms and definitions are listed in this document.

ISO and IEC maintain terminology databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at https:// www .iso .org/ obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at https:// www .electropedia .org/

4 Symbols and abbreviated terms

4.1 Symbols

8 −1

c speed of light (≈ 3,0 × 10 m s )

refractive index structure constant

C

n

Nyquist frequency

f

Nyq

mean Doppler frequency shift of the echo

f

r

antenna gain in decibels

G

ant

loss factor caused by the pulse shaping

L

p

n

radio refractive index

number of antenna beam directions

N

beam

N number of coherent integrations. In this document, N is defined as the

coh coh

number excluding N

pseq

N number of elements in I and Q (I/Q) time series after coherent integrations.

data

N is also the number of elements in the Doppler spectrum

data

number of transmitted frequencies

N

freq

number of incoherent integrations

N

incoh

number of pulse sequences

N

pseq

number of sub-pulses used in phase-modulated pulse compression

N

subp

inter pulse period

T

IPP

echo power

P

echo

noise power of the receiver

P

N

noise power of the Doppler spectrum

P

n

noise power of the Doppler spectrum per Doppler velocity bin

p

n

peak output power of the transmitter

P

p

peak output power at the antenna

P

t

u

zonal wind velocity

v

meridional wind velocity

peak-to-peak voltage

V

pp

radial Doppler velocity

V

r

sample volume

V

s

V wind vector

wind

w

vertical wind velocity

Δr range resolution

η

volume reflectivity

λ radar wavelength

spectral width defined as the half-power full width

σ

3dB

spectral width defined as the standard deviation

σ

std

time width between the two 3-dB drop-off points from the peak point

τ

3dB

duration during which the transmission signal is generated

τ

d

transmitted pulse width

τ

p

H Hermitian operator (complex transposition)

T

superscript which indicates matrix transposition

*

complex conjugation

4.2 Abbreviated terms

ACS adaptive clutter suppression

A/D analog-to-digital

ADC A/D converter

BUFR binary universal form for the representation of meteorological data

COHO coherent oscillator

CRI coherent radar imaging

D/A digital-to-analog

DBS Doppler beam swinging

DCMP directionally constrained minimization of power

DSP digital signal processor

FCA full correlation analysis

FDI frequency domain interferometry

FMCW frequency modulated continuous wave

I/O input/output

I/Q in-phase (I)/quadrature-phase (Q)

IF intermediate frequency

FPGA field programmable gate array

IPP inter pulse period

ITU International Telecommunication Union

JMA Japan Meteorological Agency

LNA low noise amplifier

MTBF mean time between failures

MTTF mean time to failure

NC-DCMP norm-constrained DCMP

NF noise figure

QC quality control

RF radio frequency

RIM range imaging

RL antenna return loss

SA spaced antenna

SNR signal to noise ratio

STALO stable (stabilized) local oscillator

UHF ultra high frequency

UPS uninterruptible power supply

VHF very high frequency

VAD velocity azimuth display

VSWR voltage standing wave ratio

WMO World Meteorological Organization

WPR radar wind profiler, wind profiler radar, wind profiling radar, atmospheric radar,

or clear-air Doppler radar

5 Measurement principle

5.1 Spectral parameters of the echo

The properties of all WPR echoes are generally estimated from the properties of the Doppler spectrum.

Spectral analysis is typically applied to estimate a finite set of parameters such as signal to noise ratio

(SNR), Doppler shift and spectral (spectrum) width. Of particular importance for a WPR is the echo

generated by clear air scattering (clear-air echo). For details of the clear-air echo, see 5.2.1.

NOTE 1 For real-time signal processing to obtain the Doppler spectrum, see 6.2.2 and 6.2.6.

NOTE 2 Interchangeable with spectral width, spectrum width, is also frequently used. The two terms have

the same meaning.

The frequency distribution of the echo contains information on the radial Doppler velocity (V ) and on

r

the wind variance caused by turbulence. Figure 1 shows an example of the Doppler spectrum. The

Doppler spectrum of the echo ( S ) and the noise shown in Figure 1 were produced by a numerical

echo

simulation. In the numerical simulation, Doppler spectra composed of S and white noise were

echo

produced. The noise power of the Doppler spectrum is expressed by P . It is assumed that S follows

n echo

.

a Gaussian distribution and that each spectrum point of S follows the χ distribution with 2

echo

degrees of freedom. The frequency bandwidth of the Doppler spectrum is expressed by B . Produced

s

Doppler spectra were integrated, and the Doppler spectrum after the integration (i.e. incoherent

integration) is plotted. Therefore, the noise variance over B is smaller than the square of the noise

s

power per Doppler velocity bin (p ). The noise variance is one of the principal factors that determine

n

the sensitivity of a WPR receiver. See 6.2.2 and 7.3 for details of incoherent integration and radar

sensitivity, respectively.

In general, it is assumed that S follows a Gaussian distribution. This assumption is generally applied

echo

for the clear-air echo. In this assumption, only the zeroth, first, and second order moments of the echo

are taken into account when determining the spectral parameters. This assumption shall be carefully

discriminated from the assumption that the received signal is the realization of one or more Gaussian

stochastic processes, which include those in both radio wave scattering and of course, uncorrelated

(white) noise. In the event of deviations from this assumption, higher order moments may be considered.

The noise produced in the receiver (receiver noise) can generally be regarded as white noise. For details

of the receiver noise, see 6.2.5.4.

Key

X Doppler velocity

Y intensity

NOTE

— For the definition of the symbols which are not listed in the keys, see text.

— The thin solid curve is an example of a Doppler spectrum which contains the Doppler spectrum of S and

echo

the white noise. The thick solid curve is the sum of P and the idealized S which follows a Gaussian

n echo

distribution and does not have perturbation. The idealized S and P are darkly and lightly shaded,

echo n

respectively. The power of the idealized S is denoted by P . f , σ , σ , and the peak intensity of

echo echo r std 3dB

the idealized S ( p ) is indicated by arrows.

echo k

Figure 1 — Example of Doppler spectrum and spectral parameters

Echo power ( P ), V , and the spectral width are the principal parameters that characterizes the

echo r

echo. They are referred to as the spectral parameters. V is computed from the mean Doppler frequency

r

shift of the echo ( f ). P and f are also the zeroth and first order moment of S , respectively.

r echo r echo

The spectral width defined as the standard deviation (σ ) is the square root of the second order

std

moment of S (see Figure 1). P , f , and σ are expressed by Formula (1), (2) and (3):

echo echo r std

PS= ()fdf (1)

echo echo

∫

fS ()fdf

echo

∫

f = (2)

r

Sf df

()

echo

∫

ff− Sf df

() ()

recho

∫

σ = (3)

std

Sf()df

echo

∫

where f is the Doppler frequency.

The relation between f and V is expressed by Formula (4):

r r

λ

Vf≈− (4)

rr

In Formula (4), V is defined to be positive when its direction is away from the antenna. However, when

r

one prefers to use the sign definition of V as that of f , V can be defined to be positive when its

r r r

direction is toward the antenna. In any case, the direction of V shall be defined clearly in the design

r

and manufacture of the WPR in order to prevent possible mistakes in the design, manufacture,

operation, and maintenance of the WPR. In this document, V is defined to be positive when its direction

r

is away from the antenna.

The spectral width can be also defined as the half-power full width (σ ) or half-power half width of

3dB

σ

3dB

the echo (i.e. ). When S is assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution, σ can be calculated

echo 3dB

by the relation of Formula (5):

σσ= 22ln2 (5)

3dB std

Because the spectral width can be expressed under the above-mentioned definitions, the definition

of the spectral width shall be given explicitly. It shall be noted that the spectral width is not only

determined by wind perturbation caused by turbulence, but also contains broadening effects due to the

[4]

angular and vertical extension of the sample volume . Details of the sample volume are described in

7.1.2.

In the estimation of the spectral parameters, P is also estimated. SNR is expressed by Formula (6):

n

P

echo

SNR= (6)

P

n

In the digital signal processing for estimating the spectral parameters and P , the noise power per

n

Doppler velocity bin ( p ) is generally used. p is expressed by Formula (7):

n n

Δf

pP= (7)

nn

B

s

where Δf is the frequency resolution of the Doppler spectrum (i.e. interval of the Doppler frequency

bins). It is noted that interference from other radio sources that contaminates the received signal has

frequency dependency in general. Therefore, contamination due to the radio interference can produce a

frequency dependency of the noise. Details of the interference from radio sources are described in 5.2.4

and 10.6.

When it is assumed that S follows a Gaussian distribution and SNR is infinite, the estimation error

echo

of Doppler velocity or the spectral width, ε , can be estimated by Formula (8):

v

σ

2

v

ε =K (8)

vv

T

c

where

K is the coefficient;

v

-1

σ is the spectral width defined as the standard deviation in m s ;

v

T is the measurement period in s.

c

When the antenna beam direction is changed after collecting a Doppler spectrum (i.e. after

NN N times transmissions and receptions) or after collecting all of the Doppler spectra used

pseq cohdata

in incoherent integration (i.e. after NN NN times transmissions and receptions),

pseq cohdataincoh

TT= NN NN . When the antenna beam direction is changed on a pulse-to-pulse basis,

cIPP pseq cohdataincoh

TT= NN NN N . See 6.2.3.2.5 for details about the timing change of the antenna

cIPP beam pseq cohdataincoh

beam direction.

K is defined by Formula (9):

v

λ

2

Kk= (9)

verr

2

where

k is the coefficient;

err

λ

is the radar wavelength;

Formulae (8) and (9) are derived from Formulae (13) and (14) in Reference [5], respectively. The value

of k (see Reference [5]) is listed in Table 1.

err

Table 1 — Value of k

err

Parameter Least square method Moment method

Doppler velocity 0,63 0,38

Spectral width 0,60 0,24

Error estimations of the spectral parameters when considering SNR is described in 6.3, 6.4, and 6.5 of

Reference [2].

5.2 Sources of received signals

5.2.1 Turbulent scattering and partial reflection

The ability to detect the clear-air echo is the most important characteristic of a WPR. It makes a WPR

capable of determining vertically resolved profiles of the wind vector from the measured Doppler shift

of the clear-air echo. There are two major mechanisms that produce echoes in clear air: turbulent

scattering from atmospheric turbulence and partial reflection from the horizontally stratified

atmosphere. Partial reflection is also referred to as Fresnel scattering. Atmospheric turbulence

produces perturbation of n , and perturbations of n with the scale of half of λ (i.e. Bragg scale) is a

source of radio wave scattering in clear air.

NOTE The clear-air echo is a return from a radio wave scattering caused by variations of the radio refractive

index n , and does not include scatterings from hard targets in the air (e.g. hydrometeors, insects, birds, and

aircrafts).

n in the neutral (i.e. unionized) atmosphere is given by Formula (10):

p e

−−51

n=+17,,76×+10 3731× 0 (10)

T

T

where

p

is the atmosphere pressure in hPa;

T

is the atmospheric temperature in K;

e

is the partial pressure of water vapour in hPa.

When perturbations of n is isotropic, turbulent scattering is also isotropic.

The refractive index structure constant C is defined as in Formula (11):

n

2 23/

nr+δδrn− rC= r (11)

[]() ()

n

where r is an arbitrary position and δr is a small distance between two spaced locations, respectively.

Because T and e are perturbed by turbulence and n depends on them, C significantly varies due to

n

the atmospheric conditions that determine T and e [see Formula (10)].

The frequency of a WPR is generally selected so that turbulent scattering occurs in the inertial sub-

range of turbulence. Frequencies between 50 MHz and 3 GHz have generally been used for WPRs.

In the inertial sub-range, the energy cascades from the largest eddies to the smallest ones through an

inertial (and inviscid) mechanism. The inertial sub-range exists between the inner scale of turbulence

( l ) and the buoyancy length scale (L ). l is the scale for determining the transition region between

0 B 0

the viscous and inertial sub-ranges, and L is the scale for determining the transition region between

B

the inertial and buoyancy sub-ranges. In the buoyancy sub-range, the turbulent eddies become

flattened and anisotropic. In the viscous sub-range, the smallest eddy is strongly affected by viscosity,

and kinetic energy is converted into heat. The transition from the inertial range to the viscous range

explains the reason why the maximum attainable height coverage for WPRs decreases towards smaller

wavelengths. Viscous subrange is also referred to as dissipative subrange. Long wavelengths (i.e. low

frequencies) whose Bragg scale lie in buoyance sub-range and short wavelengths (i.e. high frequencies)

whose Braggscale lie in the viscous sub-range are not preferable from the viewpoint of radar

sensitivity. See 3.4.2 and 7.3.3 of Reference [1] for more details of the inertial sub-range.

Horizontally stratified layers having sharp vertical gradients of n are known to produce partial

reflection. The echo intensity from partial reflection shows a strong dependency on the zenith angle.

Near zenith it reaches a maximum and decreases rapidly as the zenith angle increases.

The partial reflection coefficient ρ is given by Formula (12):

+l/2

1 1dn

2 − jzκ

ρ = edz (12)

∫

−l/2

4 ndz

where

l

is the thickness of the stratified layer;

z

is the altitude;

κ

is the wave number given as κ =4πλ/ .

See 3.4.3 of Reference [1] for more details of partial reflection. Partial reflection is not observed at the

[1]

UHF and microwave bands .

The intensity of the clear-air echo is determined by the strength of n perturbation caused by turbulence

or by the strength of vertical gradient of n caused by horizontally stratified layers.

5.2.2 Echo in precipitation

Raindrops, hail, snow crystals, ice crystals, and mixed-phase particles in precipitation (precipitation

echo) are also sources of echoes. The intensity of the precipitation echo is frequently comparable to

that of the clear-air echo for the VHF band and is generally greater than that of the clear-air echo for the

UHF band.

If both the precipitation echo and the clear-air echo exist in the Doppler spectrum, the measured

Doppler velocity can be a combination of wind (velocity of clear air) and terminal velocity of

hydrometeors relative to the ground. In this case, the vertical wind cannot be estimated correctly when

both scattering contributions cannot be separated. Nevertheless, the horizontal wind can usually be

derived accurately since the horizontal displacement velocity of the rather small hydrometeors is a

good proxy for the horizontal wind. WPRs using the UHF band generally measure the horizontal wind

velocity at a greater height in precipitation than in clear air.

5.2.3 Clutter

Undesired echoes are referred to as clutter. Because clutter contaminates the Doppler spectrum, it can

significantly decrease the quality of measurement products obtained by the WPR.

The sources of clutter are as follows:

— Clutter from sources fixed on the ground, referred to as ground clutter: Land, grass, trees on hills

and mountains, and high metallic structures (e.g. towers, buildings, and power lines) are the major