ISO/ASTM TR 52905:2023

(Main)Additive manufacturing of metals — Non-destructive testing and evaluation — Defect detection in parts

Additive manufacturing of metals — Non-destructive testing and evaluation — Defect detection in parts

This document categorises additive manufacturing (AM) defects in DED and PBF laser and electron beam category of processes, provides a review of relevant current NDT standards, details NDT methods that are specific to AM and complex 3D geometries and outlines existing non‑destructive testing techniques that are applicable to some AM types of defects. This document is aimed at users and producers of AM processes and it applies, in particular, to the following: — safety critical AM applications; — assured confidence in AM; — reverse engineered products manufactured by AM; — test bodies wishing to compare requested and actual geometries.

Fabrication additive de métaux — Essais et évaluation non destructifs — Détection de défauts dans les pièces

Le présent document catégorise les défauts de fabrication additive (FA) de la catégorie de procédés DED et PBF par laser et faisceau d'électrons, fournit un examen des normes d'END actuelles pertinentes, détaille des méthodes d'END qui sont spécifiques à la FA et aux géométries 3D complexes et définit des techniques d'essais non destructifs existantes qui s'appliquent à certains types de défauts de FA. Le présent document est destiné aux utilisateurs et aux producteurs de procédés de FA et s'applique, en particulier, à ce qui suit: — les applications de FA critiques pour la sécurité; — la confiance assurée dans la FA; — les produits rétroconçus fabriqués par FA; — les organismes d'essai souhaitant comparer les géométries demandées et les géométries réelles.

General Information

Standards Content (Sample)

TECHNICAL ISO/ASTM TR

REPORT 52905

First edition

2023-06

Additive manufacturing of metals —

Non-destructive testing and evaluation

— Defect detection in parts

Fabrication additive de métaux — Essais et évaluation non destructifs

— Détection de défauts dans les pièces

Reference number

© ISO/ASTM International 2023

© ISO/ASTM International 2023

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may

be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on

the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below

or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester. In the United States, such requests should be sent to ASTM International.

ISO copyright office ASTM International

CP 401 • Ch. de Blandonnet 8 100 Barr Harbor Drive, PO Box C700

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva West Conshohocken, PA 19428-2959, USA

Phone: +41 22 749 01 11 Phone: +610 832 9634

Fax: +610 832 9635

Email: copyright@iso.org Email: khooper@astm.org

Website: www.iso.org Website: www.astm.org

Published in Switzerland

ii

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

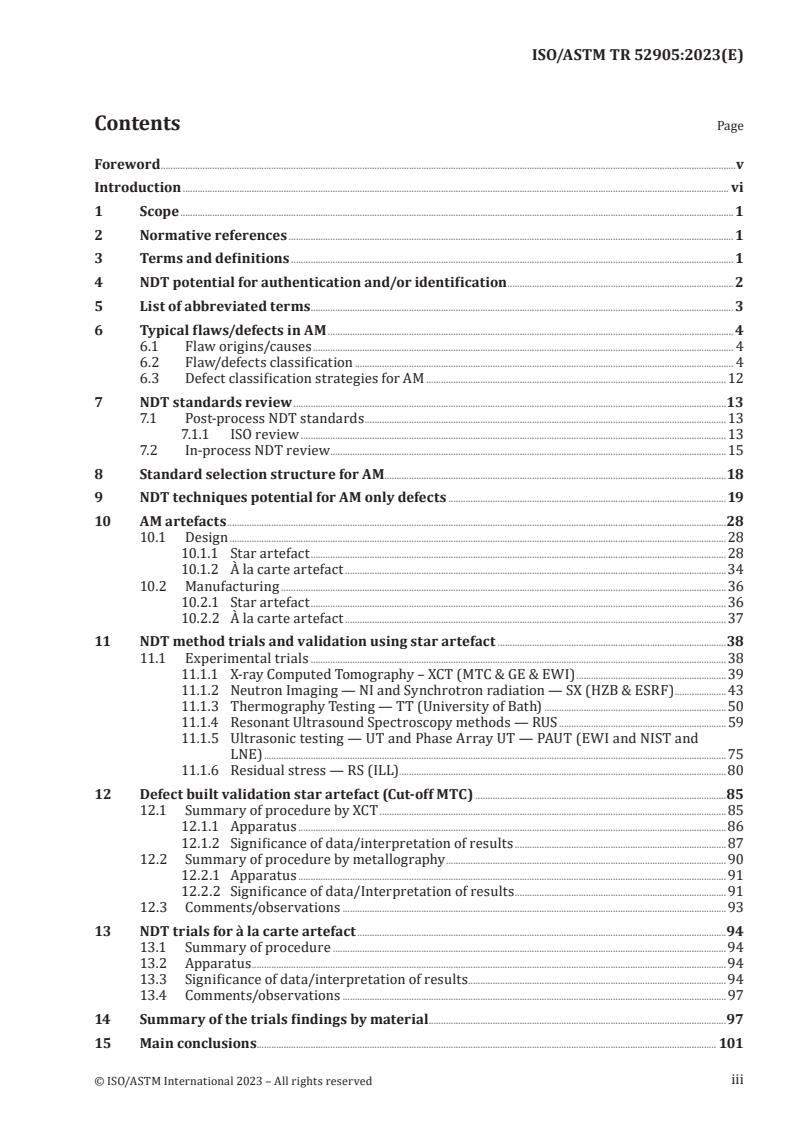

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction . vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 NDT potential for authentication and/or identification . 2

5 List of abbreviated terms . 3

6 Typical flaws/defects in AM .4

6.1 Flaw origins/causes . 4

6.2 Flaw/defects classification . 4

6.3 Defect classification strategies for AM .12

7 NDT standards review .13

7.1 Post-process NDT standards . 13

7.1.1 ISO review . 13

7.2 In-process NDT review .15

8 Standard selection structure for AM .18

9 NDT techniques potential for AM only defects .19

10 AM artefacts .28

10.1 Design .28

10.1.1 Star artefact .28

10.1.2 À la carte artefact .34

10.2 Manufacturing .36

10.2.1 Star artefact . 36

10.2.2 À la carte artefact . 37

11 NDT method trials and validation using star artefact .38

11.1 Experimental trials .38

11.1.1 X-ray Computed Tomography – XCT (MTC & GE & EWI) .39

11.1.2 Neutron Imaging — NI and Synchrotron radiation — SX (HZB & ESRF) . 43

11.1.3 Thermography Testing — TT (University of Bath) .50

11.1.4 Resonant Ultrasound Spectroscopy methods — RUS . 59

11.1.5 Ultrasonic testing — UT and Phase Array UT — PAUT (EWI and NIST and

LNE) . 75

11.1.6 Residual stress — RS (ILL) .80

12 Defect built validation star artefact (Cut-off MTC) .85

12.1 Summary of procedure by XCT .85

12.1.1 Apparatus .86

12.1.2 Significance of data/interpretation of results .87

12.2 Summary of procedure by metallography .90

12.2.1 Apparatus . 91

12.2.2 Significance of data/Interpretation of results . 91

12.3 Comments/observations .93

13 NDT trials for à la carte artefact .94

13.1 Summary of procedure .94

13.2 Apparatus .94

13.3 Significance of data/interpretation of results.94

13.4 Comments/observations .97

14 Summary of the trials findings by material .97

15 Main conclusions. 101

iii

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

Annex A (informative) Causes and effects of defects in wire DED and PBF process . 104

Annex B (informative) Review of existing NDT standards for welding or casting for

application of post build AM flaws . 106

Annex C (informative) Star artefacts using during the trials . 111

Annex D (informative) Summary of star artefact manufacturing and NDT technologies for

trials . 115

Annex E (informative) XCT parameters and XCT set up used for inspection and validation . 118

Annex F (informative) Parameters and set up for Neutron Image (NI) and Synchrotron (Sx)

inspection . 135

Annex G (informative) Set up for PT and SHT inspection .141

Annex H (informative) Ultrasonic test . 144

Annex I (informative) Residual stress characterisation of Ti6Al4V by Neutron diffraction . 155

Bibliography . 157

iv

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular, the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation of the voluntary nature of standards, the meaning of ISO specific terms and

expressions related to conformity assessment, as well as information about ISO's adherence to

the World Trade Organization (WTO) principles in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT), see

www.iso.org/iso/foreword.html.

The committee responsible for this document is ISO/TC 261, Additive manufacturing, in cooperation with

ASTM Committee F42, Additive manufacturing technologies, on the basis of a partnership agreement

between ISO and ASTM International with the aim to create a common set of ISO/ASTM standards

on additive manufacturing, in collaboration with the European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

Technical Committee CEN/TC 438, Additive manufacturing, in accordance with the Agreement on

technical cooperation between ISO and CEN (Vienna Agreement).

Any feedback or questions on this document should be directed to the user’s national standards body. A

complete listing of these bodies can be found at www.iso.org/members.html.

v

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

Introduction

In response to the urgent need for standards for Additive Manufacturing (AM), this document initially

indicates Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) methods with potential to detect defects and determine

residual strain distribution that are generated in AM processes. A number of these methods were

verified. The strategy adopted was to review existing NDT standards for matured manufacturing

processes which are similar to AM, namely casting and welding. This potentially reduces the number of

standards required to comprehensively cover the defects in AM. For identified AM unique defects, this

document proposes a two-level NDT approach: a star artefact as an Initial Quality Indicator (IQI) and

à la carte artefact where an example shows the specific steps to follow for the very specific unique AM

part to be built, paving the way for a structured and comprehensive framework.

Most metal inspection methods in NDT use ultrasound or X-rays, but these techniques cannot always

cope with the complicated shapes typically produced by AM. In most circumstances X-ray computed

tomography (CT) is a more suitable method, but it also has limitations and room for improvement or

adaptation to AM, on top of being a costly method both in time and money.

This document includes post-process non-destructive testing of additive manufacturing (AM) of

metallic parts with a comprehensive approach. It covers several sectors and a similar framework can

be applied to other materials (e.g. ceramics, polymers, etc.). In-process NDT and metrology standards

are referenced as they are being developed. This document presents current standards capability to

detect which of the Additive Manufacturing (AM) flaw types and which flaws require new standards,

using a standard selection tool. NDT methods with the highest potential will be tested.

vi

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

TECHNICAL REPORT ISO/ASTM TR 52905:2023(E)

Additive manufacturing of metals — Non-destructive

testing and evaluation — Defect detection in parts

1 Scope

This document categorises additive manufacturing (AM) defects in DED and PBF laser and electron

beam category of processes, provides a review of relevant current NDT standards, details NDT methods

that are specific to AM and complex 3D geometries and outlines existing non-destructive testing

techniques that are applicable to some AM types of defects.

This document is aimed at users and producers of AM processes and it applies, in particular, to the

following:

— safety critical AM applications;

— assured confidence in AM;

— reverse engineered products manufactured by AM;

— test bodies wishing to compare requested and actual geometries.

2 Normative references

The following documents are referred to in the text in such a way that some or all of their content

constitutes requirements of this document. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For

undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 11484, Steel products — Employer's qualification system for non-destructive testing (NDT) personnel

ISO/ASTM 52900, Additive manufacturing — General principles — Fundamentals and vocabulary

ASTM E1316, Terminology for Nondestructive Testing

EN 1330-2, Non-destructive testing — Terminology — Part 2: Terms common to the non-destructive

testing methods

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions given in ISO/ASTM 52900, ASTM E1316,

EN 1330-2, ISO 11484, and the following apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at https:// www .iso .org/ obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at https:// www .electropedia .org/

3.1

flaw type

identifiable features that defines a specific flaw

Note 1 to entry: defect term, this word is used when a flaw that does not meet specified acceptance criteria and

is rejectable.

Note 2 to entry: Flaw term, an imperfection or discontinuity that is not necessarily rejectable

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

3.2

lack of fusion

LOF

type of process-induced porosity, in which the powder or wire feedstock is not fully melted or fused

onto the previously deposited substrate

Note 1 to entry: In PBF, this type of flaw can be an empty cavity, or contain unmelted or partially fused powder,

referred to as unconsolidated powder.

Note 2 to entry: LOF typically occurs in the bulk, making its detection difficult.

Note 3 to entry: Like voids, LOF can occur on the build layer plane (layer/horizontal LOF) or across multiple build

layers (cross layer/vertical LOF).

3.3

unconsolidated powder

unmelted powder that due to process failure was not melted and became trapped internally

3.4

layer shift

when it is disturbed by a magnetic field a layer or a number of layers are shifted away from

the other build layers

Note 1 to entry: see stop/start for PBF laser/E beam.

3.5

trapped powder

unmelted powder that is not intended for the part but is trapped within internal part cavities

3.6

porosity

presence of small voids in a part making it less than fully dense

Note 1 to entry: Porosity may be quantified as a ratio, expressed as a percentage of the volume of voids to the

total volume of the part.

[SOURCE: ISO/ASTM 52900:2019, 3.11.8]

4 NDT potential for authentication and/or identification

Some of the NDT methods in this technical report have the additional potential to extract authentication

and/or identification apparatus or design embedded in the design of the AM part. Such a potential

clearly depends on the material(s), geometry and process selected to fabricate the part, however

the design information and AM data file can embed in its geometry or texture ad-hoc devices that

potentially could be extracted by NDT techniques. ISO/TC 292 specifies and maintains a number of

standards supporting such devices within the ISO referential, and are fully applicable to AM digital

information. The specific requirements of design techniques, materials, processes, NDT modalities and

applications, however, still require careful evaluation, selection and classification.

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

5 List of abbreviated terms

AM additive manufacturing

BAE British Aerospace and Engineering Systems

EB-PBF electron beam powder bed fusion

ESFR European Synchrotron Research Facility

EWI Edison Welding Institute

FMC full matrix capture

GE-PD general electric powder division

HZB Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin

ILL Institute Laue-Langevin

IR infrared

IRT infrared thermography

J & J Johnson & Johnson

LNE laboratoire national de métrologie et d'essais

PBF-LB laser powder bed fusion

DED-LB laser directed energy deposition

MTC The Manufacturing Technology Centre

ND neutron diffraction

NDE non-destructive evaluation

NDT non-destructive testing

NI neutron Imaging

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

NLA non-linear acoustic testing

NLR non-linear resonance testing

PAUT phase array ultrasound testing

PCRT process compensated resonance testing

PT pulse thermography

RAM resonance acoustic method

ROI Region of interest

SX X-ray synchrotron

SHT step heating thermography

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

TFM total focusing method

TMS the modal shop

UoB university of bath

XCT X-ray computed tomography

6 Typical flaws/defects in AM

6.1 Flaw origins/causes

The causes of defects across different types of AM processes can be quite different, but the defects that

they generate can be remarkably similar. Detecting the defects also does not depend on the cause, and

in general only the size and geometry (and potentially morphology) of the defect matters for detection.

[21]

The causes and effects of a number of AM flaws have been reported in the European project AMAZE .

Table A.1 and Table A.2 give explanations of the mechanisms by which these flaws are generated

and those mechanisms are linked to the process parameters selected and the resulting processing

conditions, see ISO 11484. Understanding the conditions under which flaws are generated and

simplifying the terminology used to describe these flaws will aid the drive for quality improvement

required for widespread implementation of the technology.

The flowchart displayed in Figure 1 gives an idea of the complexity of flaw generation within the

PBF process. As can be seen, the generation of one flaw type can result in an anomalous processing

condition, which in turn generates a second flaw. For example, the presence of a thick layer or low laser

(or electron beam) power can lead to under-melting, which in turn can lead to unconsolidated powder.

Coupled with the tendency of the power source to decrease the surface energy of unconsolidated

powder under the action of surface tension, ensuing ball formation may arise due to shrinkage and

worsened wetting, leading to pitting, an uneven build surface, or an increase in surface roughness; see

EN 1330-2.

Therefore, even when there are multiple causes, a single flaw type or conditions can be generated

(excessive surface roughness) causing failure by a single failure mode (surface cracking leading to

reduced fatigue properties). Alternatively, it is also conceivable that a single flaw type or condition can

cause failure by several different failure modes.

6.2 Flaw/defects classification

Post-built AM flaws have been identified based on a report from the FP7 European AMAZE project.

Potential flaws in directed energy deposition (DED) and powder bed fusion (PBF) are listed in Table 1

and Table 2 respectively. A brief description for each flaw type is also given in the tables.

Due to the similarity in manufacturing, defects from welding and casting bear some resemblance to

defects from AM processes such as PBF and DED. Defects in post-built PBF and DED parts are identified

and listed in EN 1330-2, ASTM E1316 and References [22]. As noted in Table 1 and Table 2, both

technologies have common defects such as porosity, inclusions, undercuts, geometry, LOF, and a rough

surface texture. However, the mechanisms for PBF and DED defect generation are very different, and

more importantly, the relative abundance of each defect type will be very different due to the melting

and solidification mechanisms involved (and the significantly higher thermal gradients present in DED).

DED involves imparting a momentum into the melt pool rather than melting the powder that is already

present. The important difference between the two methods is that of timescales.

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

Key

machine: inputs/choices

AM part: resulting defect/flaw

process: resulting condition

common type of failure

Figure 1 — Causes, mode of failures and defect formation in PBF AM (see ISO/ASTM 52900)

In PBF, there is a balance of timescales between melting and re-solidification. If the melt rate is too

low, then the melt pool can become unstable and break into multiple pools. If the melt rate is too high,

powder partially melts in front of the melt pool, which can cause defects or heat affected zones. In DED,

this balance is not relevant, but the powder (or wire) that is fed into the melt pool can melt sufficiently

quickly. The issue of adding cold material (with a given momentum) to a melt pool is not well understood,

but has a large effect on the Marangoni convection direction and thermal gradients present. It is likely

that the melt pool depth will be much shallower (which may reduce powder surrounding the melt pool)

and that the thermal gradients less severe (which cause a flatter melt pool), though this depends on the

wetting between substrate (which has no surrounding powder) and the melt pool. This difference in

the melt pool dynamics impacts its shape.

This has two important consequences, grain growth and bubble dynamics. Internal defects are

attributable to cracking, pores, or lack of material. Cracking has many causes, but is generally related

to the grain boundary (apart from solidification cracking). Note that the issue of “spattering” that is

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

believed to be prominent in DED (or indeed welding) is still a significant issue in PBF. For L-PBF the

issue is that of ablation at the surface of the melt pool caused by the large thermal gradients. For EB-

PBF the problem occurs from two mechanisms; ablation and charging of the powder.

Table 1 — Typical flaws in directed energy deposition

Flaw type Description

Poor surface The surface roughness on the part does not meet the target specification for the part.

finish Measurement of the surface roughness is considered out-of-scope for NDT however, visual

examination can be included.

Porosity Typically spherical in shape and contains gas. Porosities can grow in a line to form a chain

or elongated porosity.

Incomplete fusion Fusion between the entire base metal surfaces and between adjoining welds are not com-

plete. This occurs when new material has been used and the build parameters have not

been optimised. Typically, this flaw is eliminated as the process improved when all parame-

ters have been optimised.

Undercuts at the A groove melted into the base metal adjacent to the weld toe or weld face and left unfilled

toe of the welds by weld metal.

between adjoining

weld beads

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

TTabablele 1 1 ((ccoonnttiinnueuedd))

Flaw type Description

Non-uniform weld These indicate errors in the process which can risk integrity of the build. Internal flaws

bead and fusion caused by this can be void, porosity, or incomplete fusion.

characteristic

Hole or void Typically occurs internally in the built part as shown in the micrograph below. It is difficult

to detect by physical examination of the part.

Non-metallic Inclusions can come from the powder or the wire feedstock. Some inclusions are intention-

inclusions ally added to the powder to improve the process (e.g. for oxidation) but they could also be

caused by contaminants in the process.

Cracking Cracking can develop from internal holes or voids which then grows to the external surface.

Lack of geometri- Variation of the part dimension from the CAD model will not be currently part of the re-

cal accuracy/steps view. Nevertheless, steps and gross variation which can be detected by visual examination

in the part are included.

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

Table 2 — Typical flaws in powder bed fusion

Flaw type Description

Unconsolidat- Unconsolidated powder leading to porosity or voids. The morphology is different to gas generated pores, but the geometry

ed powder and size are not dissimilar. The image below is an example taken from RASCAL project.

Trapped pow- Unmelted powder that is not intended for the part is trapped within part cavities.

der

Layer defect Void or porosity with or without unconsolidated powder that grows on the build layer plane in a connected or semi-connected

(Horizontal manner. The image below is a vertical slice of an X-ray computed tomography scan.

lack of fusion)

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

TTabablele 2 2 ((ccoonnttiinnueuedd))

Flaw type Description

Cross layer Void or porosity with or without unconsolidated powder that grows along the build axis in a connected or semi-connected

(Vertical lack manner. The images below show vertical and horizontal slices from an X-ray computed tomography scan.

of fusion)

Vertical slice view.

Top slice view.

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

TTabablele 2 2 ((ccoonnttiinnueuedd))

Flaw type Description

Porosity Typically spherical in shape and contains gas. Porosities can grow in a line to form a chain or elongated porosity. The image

below is a horizontal slice of an X-ray computed tomography scan.

Poor surface The surface roughness on the part does not meet the specification. For example, the surface roughness is higher than ac-

[24]

finish ceptable limit .

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

TTabablele 2 2 ((ccoonnttiinnueuedd))

Flaw type Description

P = 50 W, V = 200 m/s

P = 195 W, v= 1 200 m/s

Layer shift/ Variation of the part dimension from the CAD model will not be currently part of the review. Nevertheless, steps and gross

lack of variation which can be detected by visual examination are included.

geometrical

accuracy/

steps in the

part

Reduced A certain region of the part has different mechanical properties to the rest of the part.

mechanical

properties

Inclusions Inclusions can come from the contaminants in the powder. The image below is an XCT image of an inclusion taken from

project AMAZE 2.

Void Flaws created during the build process that are empty pockets or filled with partially or wholly un-sintered powder, or

partially or wholly un-fused wire. These pockets can exist in a variety of shapes and sizes. The image below is a horizontal

slice of an X-ray computed tomography scan.

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

TTabablele 2 2 ((ccoonnttiinnueuedd))

Flaw type Description

6.3 Defect classification strategies for AM

As pointed out in ISO 11484 and Reference [25], there are longstanding NDE standard defect classes

for conventionally manufactured cast, wrought, forged, and welded production parts. The defects

produced by these conventional processes will generally not be similar to those produced by AM

processes. In addition, the NDE signal attenuation characteristics in AM parts may differ from those

in conventional parts. Therefore, legacy physical reference standards and NDE procedures can be used

[25]

with caution when inspecting AM parts . This implies that until an accepted AM defect classification

and associated NDE detection limits for technologically relevant AM defects are established, the NDE

methods and acceptance criteria used for AM parts will remain part specific to design point. Variation

of AM process parameters and disruptions during build may induce a variety of defects (anomalies) in

AM parts that can be detected, sized, and located by NDE, see ISO/ASTM 52900.

In addition to defect classification strategies based on NDE detection limits for technologically relevant

defects, or acceptance criteria for the minimum allowable defect sizes, a classification strategy based on

the physical attributes possessed by defects is also possible and, perhaps, is more intuitive. For example,

defect morphology, orientation, size, and location have been found to be useful attributes for classifying

defects. Together, physical defect attributes such as morphology, orientation, size, and location provide

a powerful framework for classifying defects and can be used to complement defect classification

strategies delimited by NDE capability (minimum detectable flaw size) or acceptance criteria (critical

initial flaw size). Ultimately, the goal is to determine which of the physical defect attribute(s) play a

prominent role in influencing properties and performance.

Further refinement of NDE is possible by looking at still other physical defect attributes related to

morphology, orientation, size and location. For example, in Reference [30], tensile tests on 17-4 PH

stainless steel AM dogbones were carried out to show effect of defects on its mechanical properties.

The results revealed that the number of defects exhibited the strongest correlation to yield strength

compared to the other attributes. In addition to the defect attributes of morphology, orientation, size,

and location discussed above, the selection of an appropriate NDE method is governed by a range of

[21][22]

practical and material considerations . Practical considerations include

a) special equipment and/or facilities requirements,

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

b) cost of examination,

c) personnel and facilities qualification,

d) geometrical complexity of the part,

e) part size and accessibility of the inspection surface or volume relative to NDE used (for example the

ability to detect embedded flaws), and

f) process history and post-processing (see ASTM E3166).

While application of conventional NDE techniques is possible for AM parts with simple geometries,

topology optimized AM parts with more complex geometries require specialized NDE techniques. The

ability of each technique to detect different types of defects, as well as to locate them in the interior or

exterior surface of a part is listed. Finally, the NDE techniques are further characterized by the ability

to globally screen or detect and locate a defect.

7 NDT standards review

7.1 Post-process NDT standards

In DED, material is fused together by melting as it is being deposited. DED processes are primarily used

to add features to an existing structure or to repair damaged or worn parts. DED has many variants of

processes. The material deposited can be either powder or wire based. The heat source can be a laser,

electron beam, electric arc among others. DED processes have similarities to welding processes, and

consequently the flaws generated in DED are expected to be similar to the flaws generated in welding.

For this reason, the NDT standards for welding have been used in the review.

In PBF, powder is deposited onto a build platform bed and selectively fused using a localized energy

source (typically electron or laser beam) to form a section through the component. The build platform

is then lowered and the process is repeated until the part is produced. Unlike DED, PBF processes do

not have similarities to welding. However, there are flaws generated in PBF such as voids and porosity

that have some similarities to welding flaws. Therefore, the review of NDT standards for welding is

still relevant to PBF. In addition to welding, some common casting flaws, gas porosity, cracking and

inclusion, are similar to DED and PBF flaws. For this reason, NDT standards for castings have also been

reviewed and their applicability to AM flaws is assessed.

7.1.1 ISO review

7.1.1.1 Welding standards

The NDT standards for welding comprise of a number of standards that cover different aspects of

inspection in welding. This is described by the tree diagrams in ISO 17635:2016, Figure B.1. The welding

quality standards are specified in ISO 5817 and ISO 10042. These standards feed into ISO 17635 which

is an interface between the quality levels and the acceptance levels for indications. This standard also

describes the NDT method selection process, which splits into six method-specific standards. These

are radiographic, eddy current, magnetic particle, penetrant, ultrasonic and visual examination. At this

stage, an NDT method has been decided, and a corresponding standard describes the test procedure

and the characterisation acceptance levels. Each method has its own limitations and it is possible that,

for a given component or a target flaw, a combination of different methods is required.

The method standards are only available for conventional NDT. For radiography and ultrasonic, there

are more sub-method standards as shown in ISO 17635:2016, Figures B.2 and B.3. NDT standards for

more advanced NDT methods are not available; for example, ultrasonic phased array, X-ray computed

tomography, and thermography. It is possible that these methods are not widely accepted and used by

NDT operators within the welding industry. However for AM, there are opportunities for new standards

to be developed for the advanced methods.

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

7.1.1.2 Casting standards

The NDT standards for casting have a simpler structure to those for welding. ISO 4990 categorises

casting flaws into surface discontinuities and internal discontinuities. There are standards for five

main conventional NDT methods. Each method is either for surface or internal discontinuities. The five

NDT methods are:

1) Visual examination ISO 11971 (surface)

2) Magnetic Particle Inspection ISO 4986 (surface)

3) Liquid Particle Inspection ISO 4987 (surface)

4) Ultrasonic examination ISO 4992 (internal) — Part 1 (general purposes) and Part 2 (highly stressed

components)

5) Radiographic testing ISO 4993 (internal)

Similar to welding, there is no standard available for advanced NDT methods for castings such as X-ray

computed tomography, phased array ultrasonic and thermography. These methods are not regarded as

standard methods in castings, although they could have been used following company specific internal

standards or procedures. Castings typically have simpler geometry compared to AM and welding.

Some NDT methods might not be suitable e.g. ultrasonic. Additionally, surface roughness for castings is

typically better than as-built AM components.

7.1.1.3 Welding and casting standards applicable to AM flaws

The summary of the review of current standards for welding and casting (see Table B.1) is shown

in Table 3. Flaws that would be covered by other types of inspection e.g. dimensional measurement

or material characterisation are categorised as ‘non-NDT’. All flaws listed in the table for DED are

generally covered by current NDT standards, except for the non-NDT ones. For PBF, seven flaws are

not covered by current NDT standards. Three of these are non-NDT, and four are flaws unique to AM

(unconsolidated powder, layer, cross layer, and trapped powder). The unique flaws require new NDT

recommendations which will be addressed in this document. It will also refer to newly developed

standards in other sectors such as aerospace.

As shown in Table 3, the following are the identified flaws unique to AM (PBF only) which require new

standards:

— Layer;

— Cross layer;

— Trapped powder;

— Unconsolidated powder;

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

Table 3 — Classification of directed energy deposition and powder bed fusion flaws

(Flaws unique to additive manufacturing are in bold)

Flaw type

Poor surface finish

Porosity

Incomplete fusion

Lack of geometrical accuracy/steps in part

Undercuts

Non-uniform weld bead and fusion charac-

teristic

Hole or void

Non-metallic inclusions

Cracking

Unconsolidated powder

Lack of geometrical accuracy/steps in part

Reduced mechanical properties

Inclusions

Void

Layer

Cross layer

Porosity

Poor surface finish

Trapped powder

7.2 In-process NDT review

Conventional NDE methods such as X-ray, UT, EC, have been used for post build inspection of Additive

manufacturing (AM) components. Due to the limited number of studies available and the technical

[21][27]

constraints, the capability of these NDE techniques is limited, indicating a technical gap . It is

foreseen that in-process monitoring can be used to improve control of the process to minimise quality

issues. In addition, in-process inspection has the added ability to inspect the part as it is built, which for

some very complex AM parts may be the only NDE capable solution.

AM processes offer freedom over other manufacturing methods, such as the integration of multiple

parts, which generally increase their geometry complexity. In order for an AM process to be successful,

the product quality can first be ensured. Typically, quality inspections are performed after the build of

© ISO/ASTM International 2023 – All rights reserved

PBF DED

Non-NDT

Common in

DED & PBF

Covered by

current stand-

ards

Unique to AM

the full part, which becomes difficult for complex geometries. Taking advantage of the unique layer-by-

layer build method, an ideal place to verify the part quality is after a layer or number of layers, with the

potential advantage to reduce or eliminate the need to inspect after the full build.

Current AM in-process monitoring relies mainly on surface measurements, potentially missing

subsurface defects. LPBF and DED AM processes work at elevated temperatures; therefore, non-contact

methods are required.

In powder bed fusion processes, problems with layer-wise coatings and untimely laser melting can

lead to porosity, stress and further variations in the built part, or of material properties. Therefore, it

is important to not only perform measurements to inspect the finished build, but also to monitor in-

process and ultimately implement an efficient feedback system tha

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.