IEC 60695-5-1:2021

(Main)Fire hazard testing - Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent - General guidance

Fire hazard testing - Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent - General guidance

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 provides guidance on the following:

a) general aspects of corrosion damage test methods;

b) methods of measurement of corrosion damage;

c) consideration of test methods;

d) relevance of corrosion damage data to hazard assessment.

This basic safety publication is primarily intended for use by technical committees in the preparation of standards in accordance with the principles laid down in IEC Guide 104 and ISO/IEC Guide 51. It is not intended for use by manufacturers or certification bodies. One of the responsibilities of a technical committee is, wherever applicable, to make use of basic safety publications in the preparation of its publications. The requirements, test methods or test conditions of this basic safety publication will not apply unless specifically referred to or included in the relevant publications. This standard is to be read in conjunction with IEC TS 60695-5-2.

This third edition cancels and replaces the second edition, published in 2002, and constitutes a technical revision. This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous edition:

a) References to IEC TS 60695-5-3 (withdrawn in 2014) have been removed.

b) References to IEC 60695-1-1 are now to its replacements: IEC 60695-1-10 and IEC 60695-1-11.

c) ISO/TR 9122-1 has been revised by ISO 19706.

d) Table 1 has been updated.

e) References to ISO 11907-2 and ISO 11907-3 have been removed.

f) Terms and definitions have been updated.

g) Text in 6.4 has been updated.

h) Bibliographic references have been updated.

Essais relatifs aux risques du feu - Partie 5-1: Effets des dommages de corrosion des effluents du feu - Recommandations générales

L'IEC 60695-5-1:2021 fournit des recommandations concernant:

a) les aspects généraux des méthodes d’essai des dommages de corrosion;

b) les méthodes de mesure des dommages de corrosion;

c) la prise en considération des méthodes d’essai;

d) la pertinence des données concernant les dommages de corrosion pour l’estimation du danger.

La présente publication fondamentale de sécurité est essentiellement destinée à être utilisée par les comités d'études dans le cadre de l'élaboration de normes conformément aux principes établis dans le Guide IEC 104 et le Guide ISO/IEC 51. Elle n'est pas destinée à être utilisée par des fabricants ou des organismes de certification. L'une des responsabilités d'un comité d'études consiste, le cas échéant, à utiliser les publications fondamentales de sécurité dans le cadre de l'élaboration de ses publications. Les exigences, les méthodes ou les conditions d'essai de la présente publication fondamentale de sécurité s'appliquent seulement si elles sont spécifiquement citées en référence ou incluses dans les publications correspondantes. Cette troisième édition annule et remplace la deuxième édition, parue en 2002 et constitue une révision technique. Cette édition inclut les modifications techniques majeures suivantes par rapport à l'édition précédente:

a) les références à l’IEC TS 60695-5-3 (supprimée en 2014) ont été supprimées;

b) les références à l’IEC 60695-1-1 correspondent désormais aux normes suivantes: IEC 60695-1-10 et IEC 60695-1-11;

c) l’ISO/TR 9122-1 a été révisée par l’ISO 19706;

d) le Tableau 1 a été mis à jour;

e) les références à l’ISO 11907-2 et à l’ISO 11907-3 ont été supprimées;

f) les termes et définitions ont été mis à jour;

g) le texte de 6.4 a été mis à jour;

h) les références bibliographiques ont été mises à jour.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 27-Oct-2021

- Technical Committee

- TC 89 - Fire hazard testing

- Drafting Committee

- WG 11 - TC 89/WG 11

- Current Stage

- PPUB - Publication issued

- Start Date

- 28-Oct-2021

- Completion Date

- 10-Sep-2021

Relations

- Effective Date

- 05-Sep-2023

Overview

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 - Fire hazard testing, Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent - General guidance - is a basic safety publication from IEC (Edition 3.0, 2021). It gives high-level guidance on how to consider, measure and interpret the corrosive effects of fire effluent (combustion gases, smoke, moisture and particulates) on electrical and electronic equipment. The standard is intended primarily for technical committees preparing other standards (per IEC Guide 104 / ISO/IEC Guide 51) and is to be read in conjunction with IEC TS 60695-5-2.

Key Topics

- Scope and purpose: Guidance on corrosion damage test methods, measurement techniques, test-method selection and the relevance of corrosion data to fire-hazard assessments.

- Fire scenarios and physical fire models: Classification of fire stages and how different fire development stages influence effluent composition and corrosivity.

- Corrosivity factors: Nature of fire effluent, environmental conditions (temperature, humidity), substrate susceptibility and combined effects that determine corrosion risk.

- Types of corrosion damage: Metal loss, moving parts seizing, conductor bridging, formation of non‑conductive films on contacts-how these can impair electrical performance.

- Measurement principles: Generation of representative fire effluents, selection of test specimens and physical fire models, and assessment approaches including indirect assessment, simulated-product testing and product testing.

- Consideration of test methods: Practical evaluation of test relevance, limitations and applicability to hazard assessment.

- Changes in 2021 edition: Updates include revised references (e.g., IEC 60695-1-10/-1-11 replacing IEC 60695-1-1), updated table(s), revised terms and definitions, and bibliographic updates.

Applications

- Primary users: IEC technical committees and standards developers who need to incorporate consistent guidance on corrosion damage into product standards and test requirements.

- Secondary reference value: safety assessors, system designers and researchers may consult the publication for background on correlating corrosivity data with hazard assessment and on choosing appropriate measurement approaches.

- Practical uses: informing the selection of corrosivity test methods, defining test specimen selection and fire models, and interpreting corrosion data when assessing post-fire functionality and safety of electrotechnical products.

Related Standards

- IEC TS 60695-5-2 (summary and relevance of test methods) - read in conjunction with this part.

- IEC 60695-1-10, IEC 60695-1-11 (replacements for IEC 60695-1-1)

- ISO 19706 (revised from ISO/TR 9122-1)

- References in the standard also point to cable combustion gas tests (e.g., IEC 60754 series) and to other parts of the IEC 60695 series.

Keywords: IEC 60695-5-1, fire hazard testing, corrosion damage, fire effluent, corrosivity test methods, hazard assessment, electrotechnical standards.

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV - Fire hazard testing - Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent - General guidance Released:10/28/2021 Isbn:9782832244401

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 - Fire hazard testing - Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent - General guidance

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

Intertek Testing Services NA Inc.

Intertek certification services in North America.

UL Solutions

Global safety science company with testing, inspection and certification.

ANCE

Mexican certification and testing association.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 is a standard published by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Its full title is "Fire hazard testing - Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent - General guidance". This standard covers: IEC 60695-5-1:2021 provides guidance on the following: a) general aspects of corrosion damage test methods; b) methods of measurement of corrosion damage; c) consideration of test methods; d) relevance of corrosion damage data to hazard assessment. This basic safety publication is primarily intended for use by technical committees in the preparation of standards in accordance with the principles laid down in IEC Guide 104 and ISO/IEC Guide 51. It is not intended for use by manufacturers or certification bodies. One of the responsibilities of a technical committee is, wherever applicable, to make use of basic safety publications in the preparation of its publications. The requirements, test methods or test conditions of this basic safety publication will not apply unless specifically referred to or included in the relevant publications. This standard is to be read in conjunction with IEC TS 60695-5-2. This third edition cancels and replaces the second edition, published in 2002, and constitutes a technical revision. This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous edition: a) References to IEC TS 60695-5-3 (withdrawn in 2014) have been removed. b) References to IEC 60695-1-1 are now to its replacements: IEC 60695-1-10 and IEC 60695-1-11. c) ISO/TR 9122-1 has been revised by ISO 19706. d) Table 1 has been updated. e) References to ISO 11907-2 and ISO 11907-3 have been removed. f) Terms and definitions have been updated. g) Text in 6.4 has been updated. h) Bibliographic references have been updated.

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 provides guidance on the following: a) general aspects of corrosion damage test methods; b) methods of measurement of corrosion damage; c) consideration of test methods; d) relevance of corrosion damage data to hazard assessment. This basic safety publication is primarily intended for use by technical committees in the preparation of standards in accordance with the principles laid down in IEC Guide 104 and ISO/IEC Guide 51. It is not intended for use by manufacturers or certification bodies. One of the responsibilities of a technical committee is, wherever applicable, to make use of basic safety publications in the preparation of its publications. The requirements, test methods or test conditions of this basic safety publication will not apply unless specifically referred to or included in the relevant publications. This standard is to be read in conjunction with IEC TS 60695-5-2. This third edition cancels and replaces the second edition, published in 2002, and constitutes a technical revision. This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous edition: a) References to IEC TS 60695-5-3 (withdrawn in 2014) have been removed. b) References to IEC 60695-1-1 are now to its replacements: IEC 60695-1-10 and IEC 60695-1-11. c) ISO/TR 9122-1 has been revised by ISO 19706. d) Table 1 has been updated. e) References to ISO 11907-2 and ISO 11907-3 have been removed. f) Terms and definitions have been updated. g) Text in 6.4 has been updated. h) Bibliographic references have been updated.

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 29.020 - Electrical engineering in general. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to IEC 60695-5-1:2002. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

IEC 60695-5-1:2021 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

IEC 60695-5-1 ®

Edition 3.0 2021-10

REDLINE VERSION

INTERNATIONAL

STANDARD

colour

inside

HORIZONTAL PUBLICATION

Fire hazard testing –

Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent – General guidance

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from

either IEC or IEC's member National Committee in the country of the requester. If you have any questions about IEC

copyright or have an enquiry about obtaining additional rights to this publication, please contact the address below or

your local IEC member National Committee for further information.

IEC Central Office Tel.: +41 22 919 02 11

3, rue de Varembé info@iec.ch

CH-1211 Geneva 20 www.iec.ch

Switzerland

About the IEC

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is the leading global organization that prepares and publishes

International Standards for all electrical, electronic and related technologies.

About IEC publications

The technical content of IEC publications is kept under constant review by the IEC. Please make sure that you have the

latest edition, a corrigendum or an amendment might have been published.

IEC publications search - webstore.iec.ch/advsearchform IEC online collection - oc.iec.ch

The advanced search enables to find IEC publications by a Discover our powerful search engine and read freely all the

variety of criteria (reference number, text, technical publications previews. With a subscription you will always

committee, …). It also gives information on projects, replaced have access to up to date content tailored to your needs.

and withdrawn publications.

Electropedia - www.electropedia.org

IEC Just Published - webstore.iec.ch/justpublished

The world's leading online dictionary on electrotechnology,

Stay up to date on all new IEC publications. Just Published

containing more than 22 000 terminological entries in English

details all new publications released. Available online and

and French, with equivalent terms in 18 additional languages.

once a month by email.

Also known as the International Electrotechnical Vocabulary

(IEV) online.

IEC Customer Service Centre - webstore.iec.ch/csc

If you wish to give us your feedback on this publication or

need further assistance, please contact the Customer Service

Centre: sales@iec.ch.

IEC 60695-5-1 ®

Edition 3.0 2021-10

REDLINE VERSION

INTERNATIONAL

STANDARD

colour

inside

HORIZONTAL PUBLICATION

Fire hazard testing –

Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent – General guidance

INTERNATIONAL

ELECTROTECHNICAL

COMMISSION

ICS 29.020 ISBN 978-2-8322-4440-1

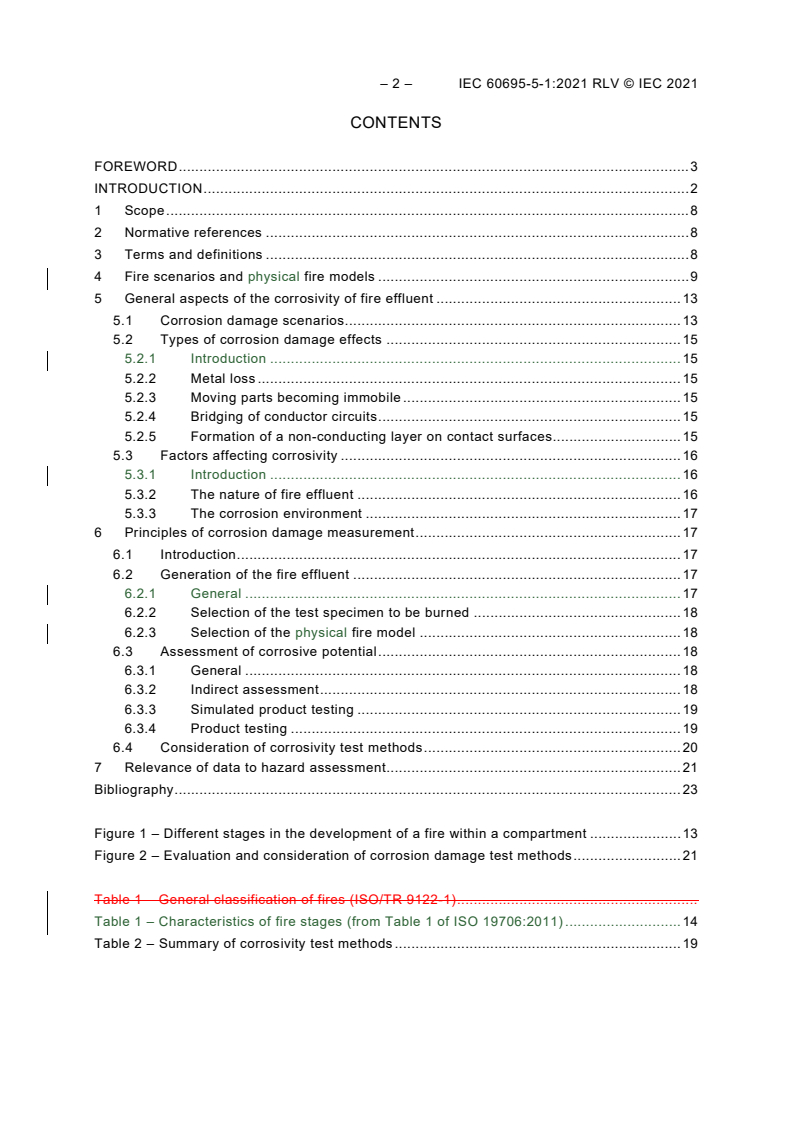

– 2 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

CONTENTS

FOREWORD . 3

INTRODUCTION . 2

1 Scope . 8

2 Normative references . 8

3 Terms and definitions . 8

4 Fire scenarios and physical fire models . 9

5 General aspects of the corrosivity of fire effluent . 13

5.1 Corrosion damage scenarios . 13

5.2 Types of corrosion damage effects . 15

5.2.1 Introduction . 15

5.2.2 Metal loss . 15

5.2.3 Moving parts becoming immobile . 15

5.2.4 Bridging of conductor circuits . 15

5.2.5 Formation of a non-conducting layer on contact surfaces. 15

5.3 Factors affecting corrosivity . 16

5.3.1 Introduction . 16

5.3.2 The nature of fire effluent . 16

5.3.3 The corrosion environment . 17

6 Principles of corrosion damage measurement . 17

6.1 Introduction . 17

6.2 Generation of the fire effluent . 17

6.2.1 General . 17

6.2.2 Selection of the test specimen to be burned . 18

6.2.3 Selection of the physical fire model . 18

6.3 Assessment of corrosive potential . 18

6.3.1 General . 18

6.3.2 Indirect assessment . 18

6.3.3 Simulated product testing . 19

6.3.4 Product testing . 19

6.4 Consideration of corrosivity test methods . 20

7 Relevance of data to hazard assessment . 21

Bibliography . 23

Figure 1 – Different stages in the development of a fire within a compartment . 13

Figure 2 – Evaluation and consideration of corrosion damage test methods . 21

Table 1 – General classification of fires (ISO/TR 9122-1) .

Table 1 – Characteristics of fire stages (from Table 1 of ISO 19706:2011) . 14

Table 2 – Summary of corrosivity test methods . 19

INTERNATIONAL ELECTROTECHNICAL COMMISSION

____________

FIRE HAZARD TESTING –

Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent –

General guidance

FOREWORD

1) The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is a worldwide organization for standardization comprising

all national electrotechnical committees (IEC National Committees). The object of IEC is to promote

international co-operation on all questions concerning standardization in the electrical and electronic fields. To

this end and in addition to other activities, IEC publishes International Standards, Technical Specifications,

Technical Reports, Publicly Available Specifications (PAS) and Guides (hereafter referred to as “IEC

Publication(s)”). Their preparation is entrusted to technical committees; any IEC National Committee interested

in the subject dealt with may participate in this preparatory work. International, governmental and non-

governmental organizations liaising with the IEC also participate in this preparation. IEC collaborates closely

with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in accordance with conditions determined by

agreement between the two organizations.

2) The formal decisions or agreements of IEC on technical matters express, as nearly as possible, an international

consensus of opinion on the relevant subjects since each technical committee has representation from all

interested IEC National Committees.

3) IEC Publications have the form of recommendations for international use and are accepted by IEC National

Committees in that sense. While all reasonable efforts are made to ensure that the technical content of IEC

Publications is accurate, IEC cannot be held responsible for the way in which they are used or for any

misinterpretation by any end user.

4) In order to promote international uniformity, IEC National Committees undertake to apply IEC Publications

transparently to the maximum extent possible in their national and regional publications. Any divergence

between any IEC Publication and the corresponding national or regional publication shall be clearly indicated in

the latter.

5) IEC itself does not provide any attestation of conformity. Independent certification bodies provide conformity

assessment services and, in some areas, access to IEC marks of conformity. IEC is not responsible for any

services carried out by independent certification bodies.

6) All users should ensure that they have the latest edition of this publication.

7) No liability shall attach to IEC or its directors, employees, servants or agents including individual experts and

members of its technical committees and IEC National Committees for any personal injury, property damage or

other damage of any nature whatsoever, whether direct or indirect, or for costs (including legal fees) and

expenses arising out of the publication, use of, or reliance upon, this IEC Publication or any other IEC

Publications.

8) Attention is drawn to the Normative references cited in this publication. Use of the referenced publications is

indispensable for the correct application of this publication.

9) Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this IEC Publication may be the subject of

patent rights. IEC shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

This redline version of the official IEC Standard allows the user to identify the changes made to

the previous edition IEC 60695-5-1:2002. A vertical bar appears in the margin wherever a

change has been made. Additions are in green text, deletions are in strikethrough red text.

– 4 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

International Standard IEC 60695-5-1 has been prepared by IEC technical committee 89: Fire

hazard testing.

This third edition cancels and replaces the second edition, published in 2002, and constitutes

a technical revision.

This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous

edition:

a) References to IEC TS 60695-5-3 (withdrawn in 2014) have been removed.

b) References to IEC 60695-1-1 are now to its replacements: IEC 60695-1-10 and

IEC 60695-1-11.

c) ISO/TR 9122-1 has been revised by ISO 19706.

d) Table 1 has been updated.

e) References to ISO 11907-2 and ISO 11907-3 have been removed.

f) Terms and definitions have been updated.

g) Text in 6.4 has been updated.

h) Bibliographic references have been updated.

The text of this International Standard is based on the following documents:

FDIS Report on voting

89/1539/FDIS 89/1543/RVD

Full information on the voting for its approval can be found in the report on voting indicated in

the above table.

The language used for the development of this International Standard is English.

This document was drafted in accordance with ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2, and developed in

accordance with ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1 and ISO/IEC Directives, IEC Supplement,

available at www.iec.ch/members_experts/refdocs. The main document types developed by

IEC are described in greater detail at www.iec.ch/standardsdev/publications.

It has the status of a basic safety publication in accordance with IEC Guide 104 and

ISO/IEC Guide 51.

In this standard, the following print types are used:

Arial bold: terms referred to in Clause 2

This standard is to be read in conjunction with IEC TS 60695-5-2.

A list of all parts in the IEC 60695 series, published under the general title Fire hazard testing,

can be found on the IEC website.

The committee has decided that the contents of this document will remain unchanged until the

stability date indicated on the IEC website under webstore.iec.ch in the data related to the

specific document. At this date, the document will be

• reconfirmed,

• withdrawn,

• replaced by a revised edition, or

• amended.

IMPORTANT – The 'colour inside' logo on the cover page of this publication indicates that it

contains colours which are considered to be useful for the correct understanding of its

contents. Users should therefore print this document using a colour printer.

– 6 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

INTRODUCTION

The risk of fire should be considered in any electrical circuit. With regard to this risk, the

circuit and equipment design, the selection of components and the choice of materials should

contribute towards reducing the likelihood of fire even in the event of foreseeable abnormal

use, malfunction or failure. The practical aim should be to prevent ignition caused by electrical

malfunction but, if ignition and fire occur, to control the fire preferably within the bounds of the

enclosure of the electrotechnical product.

In the design of an electrotechnical product the risk of fire and the potential hazards

associated with fire need to be considered. In this respect the objective of component, circuit

and equipment design, as well as the choice of materials, is to reduce the risk of fire to a

tolerable level even in the event of reasonably foreseeable (mis)use, malfunction or failure.

IEC 60695-1-10, IEC 60695-1-11, and IEC 60695-1-12 [1] provide guidance on how this is to

be accomplished.

Fires involving electrotechnical products can also be initiated from external non-electrical

sources. Considerations of this nature are dealt with in an overall fire hazard assessment.

The aim of the IEC 60695 series is to save lives and property by reducing the number of fires

or reducing the consequences of the fire. This can be accomplished by:

• trying to prevent ignition caused by an electrically energised component part and, in the

event of ignition, to confine any resulting fire within the bounds of the enclosure of the

electrotechnical product.

• trying to minimise flame spread beyond the product’s enclosure and to minimise the

harmful effects of fire effluents including heat, smoke, and toxic or corrosive combustion

products.

All fire effluent is corrosive to some degree and the level of potential to corrode depends on

the nature of the fire, the combination of combustible materials involved in the fire, the nature

of the substrate under attack, and the temperature and relative humidity of the environment in

which the corrosion damage is taking place. There is no evidence that fire effluent from

electrotechnical products offers greater risk of corrosion damage than the fire effluent from

other products such as furnishings, or building materials, etc.

The performance of electrical and electronic components can be adversely affected by

corrosion damage when subjected to fire effluent. A wide variety of combinations of small

quantities of effluent gases, smoke particles, moisture and temperature may provide

conditions for electrical component or system failures from breakage, overheating or shorting.

Evaluation of potential corrosion damage is particularly important for high value and safety-

related electrotechnical products and installations.

Technical committees responsible for products will choose the test(s) and specify the level of

severity.

The study of corrosion damage requires an interdisciplinary approach involving chemistry,

electricity, physics, mechanical engineering, metallurgy and electrochemistry. In the

preparation of this part of IEC 60695-5, all of the above have been considered.

IEC 60695-5-1 defines the scope of the guidance and indicates the field of application.

IEC TS 60695-5-2 provides a summary of test methods including relevance and usefulness.

___________

Numbers in square brackets refer to the bibliography.

IEC 60695-5-3 provides details of a small-scale test method for the measurement of leakage

current and metal loss caused by fire effluent.

– 8 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

FIRE HAZARD TESTING –

Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent –

General guidance

1 Scope

This part of IEC 60695 provides guidance on the following:

a) general aspects of corrosion damage test methods;

b) methods of measurement of corrosion damage;

c) consideration of test methods;

d) relevance of corrosion damage data to hazard assessment.

This basic safety publication is primarily intended for use by technical committees in the

preparation of standards in accordance with the principles laid down in IEC Guide 104 and

ISO/IEC Guide 51. It is not intended for use by manufacturers or certification bodies.

One of the responsibilities of a technical committee is, wherever applicable, to make use of

basic safety publications in the preparation of its publications. The requirements, test

methods or test conditions of this basic safety publication will not apply unless specifically

referred to or included in the relevant publications.

2 Normative references

The following documents are referred to in the text in such a way that some or all of their

content constitutes requirements of this document. For dated references, only the edition

cited applies. For undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including

any amendments) applies.

IEC 60695-1-1:1999, Fire hazard testing – Part 1-1: Guidance for assessing the fire hazard

of electrotechnical products – General guidelines

IEC/TS 60695-5-2:2002, Fire hazard testing – Part 5-2: Corrosion damage effects of fire

effluent – Summary and relevance of test methods

IEC/TS 60695-5-3, Fire hazard testing – Part 5-3: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent –

Leakage current and metal loss test method

IEC 60754-1:1994, Test on gases evolved during combustion of materials from cables –

Part 1: Determination of the amount of halogen acid gas

IEC 60754-2:1991, Test on gases evolved during combustion of electric cables – Part 2:

Determination of degree of acidity of gases evolved during the combustion of materials taken

from electric cables by measuring pH and conductivity

IEC 60754-2, Amendment 1 (1997)

ISO/TR 9122-1:1989, Toxicity testing of fire effluents – Part 1: General

___________

To be published.

ISO 11907-2:1995, Plastics – Smoke generation – Determination of the corrosivity of fire

effluents – Part 2: Static method

ISO 11907-3:1998, Plastics – Smoke generation – Determination of the corrosivity of fire

effluents – Part 3: Dynamic decomposition method using a travelling furnace

ISO 11907-4:1998, Plastics – Smoke generation – Determination of the corrosivity of fire

effluents – Part 4: Dynamic decomposition method using a conical radiant heater

ISO/IEC 13943:2000, Fire safety – Vocabulary

ASTM D 2671 – 00, Standard Test Methods for Heat-Shrinkable Tubing for Electrical Use

IEC 60695-1-10, Fire hazard testing – Part 1-10: Guidance for assessing the fire hazard of

electrotechnical products – General guidelines

IEC 60695-1-11, Fire hazard testing – Part 1-11: Guidance for assessing the fire hazard of

electrotechnical products – Fire hazard assessment

IEC TS 60695-5-2, Fire hazard testing – Part 5-2: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent –

Summary and relevance of test methods

IEC GUIDE 104, The preparation of safety publications and the use of basic safety

publications and group safety publications

ISO/IEC Guide 51, Safety aspects – Guidelines for their inclusion in standards

ISO 11907-1:2019, Plastics – Smoke generation – Determination of the corrosivity of fire

effluents – Part 1: General concepts and applicability

ISO 13943:2017, Fire safety – Vocabulary

ISO 19706:2011, Guidelines for assessing the fire threat to people

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions, some of which have

been taken from ISO/IEC 13943, apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following

addresses:

• IEC Electropedia: available at http://www.electropedia.org/

• ISO Online browsing platform: available at http://www.iso.org/obp

3.1

corrosion damage

physical and/or chemical damage or impaired function caused by chemical action

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC 13943, definition 25 ISO 13943:2017, 3.69]

3.2

corrosion target

sensor used to determine the degree of corrosion damage (3.1), under specified conditions

– 10 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

Note 1 to entry: This sensor may be a product, a component, or a reference material used to simulate them. It

may also be a reference material or object used to simulate the behaviour of a product or a component.

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC 13943, definition 26 ISO 13943:2017, 3.70]

3.3

critical relative humidity

level of relative humidity that causes leakage current to exceed a value defined in the product

specification

3.3

fire decay

stage of fire development after a fire has reached its maximum intensity and during which the

heat release rate and the temperature of the fire are decreasing

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.122]

3.4

fire effluent

totality of all gases and/or aerosols, (including suspended particles), created by combustion

or pyrolysis (3.9) and emitted to the environment

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC 13943, definition 45 ISO 13943:2017, 3.123]

3.5

fire effluent decay characteristics

physical and/or chemical changes in fire effluent due to time and transport

3.6

fire effluent transport

movement of fire effluent away from the location of the fire

3.5

fire scenario

detailed description of conditions, including environmental, of one or more stages from before

ignition to after completion of combustion in an actual fire at a specific location or in a real-

scale simulation

[ISO/IEC 13943, definition 58]

qualitative description of the course of a fire with respect to time, identifying key events that

characterize the studied fire and differentiate it from other possible fires

Note 1 to entry: See fire scenario cluster (ISO 13943:2017, 3.154) and representative fire scenario

(ISO 13943:2017, 3.153).

Note 2 to entry: It typically defines the ignition and fire growth processes, the fully developed fire stage, the fire

decay (3.3) stage, and the environment and systems that will impact on the course of the fire.

Note 3 to entry: Unlike deterministic fire analysis, where fire scenarios are individually selected and used as

design fire scenarios, in fire risk assessment, fire scenarios are used as representative fire scenarios within fire

scenario clusters.

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.152]

3.8

ignition source

source of energy that initiates combustion

([SO/IEC 13943, definition 97]

3.6

flashover

transition to a state of total surface involvement in a fire of combustible

materials within an enclosure

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.184]

3.7

full developed fire

state of total involvement of combustible materials in a fire

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.192]

3.8

leakage current

electrical current flowing in an undesired circuit

3.9

physical fire model

laboratory process, including the apparatus, the environment and the fire test procedure

intended to represent a certain phase of a fire

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.298]

3.10

pyrolysis

chemical decomposition of a substance by the action of heat

Note 1 to entry: Pyrolysis is often used to refer to a stage of fire before flaming combustion has begun.

Note 2 to entry: In fire science, no assumption is made about the presence or absence of oxygen.

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.316]

3.11

small-scale fire test

fire test performed on a test specimen of small dimensions

Note 1 to entry: There is no clear upper limit for the dimensions of the test specimen in a small-scale fire test. In

some instances, a fire test performed on a test specimen with a maximum dimension of less than 1 m is called a

small-scale fire test. However, a fire test performed on a test specimen of which the maximum dimension is

between 0,5 m and 1,0 m is often called a medium-scale fire test.

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.346]

3.12

smoke

visible part of a fire effluent

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC 13943, definition 150 ISO 13943:2017, 3.347]

– 12 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

4 Fire scenarios and physical fire models

During recent years, major advances have been made in the analysis of fire effluents. It is

recognized that the composition of the mixture of combustion products is particularly

dependent upon the nature of the combusting materials, the prevailing temperatures and the

ventilation conditions, especially access of oxygen to the seat of the fire. Table 1 shows how

the different stages of a fire relate to the changing atmosphere. Conditions for use in

laboratory scale tests can be derived from the table in order to correspond, as far as possible,

to full-scale fires.

Fire involves a complex and interrelated array of physical and chemical phenomena. As a

result, it is difficult to simulate all aspects of a real fire in laboratory scale apparatus. This

problem of fire model validity is perhaps the single most perplexing technical problem

associated with all fire testing.

General guidance for assessing the fire hazard of electrotechnical products is given in

IEC 60695-1-10. Guidance concerning fire hazard assessment is given in IEC 60695-1-11.

ISO 11907-1 defines terms related to smoke corrosivity as well as smoke acidity and smoke

toxicity. It presents the scenario-based approach that controls smoke corrosivity. It describes

the test methods to assess smoke corrosivity at laboratory scale and deals with test

applicability and post-exposure conditions.

After ignition, fire development may occur in different ways depending on the environmental

conditions, as well as on the physical arrangement of the combustible materials. However, a

general pattern can be established for fire development within a compartment, where the

general temperature-time curve shows three stages, plus a fire decay stage (see Figure 1).

Stage 1 (non-flaming decomposition) is the incipient stage of the fire prior to sustained

flaming, with little rise in the fire room temperature. Ignition and smoke generation are the

main hazards during this stage.

Stage 2 (developing fire) starts with ignition and ends with a rapid rise in fire room

temperature. Spread of flame and heat release are the main hazards in addition to smoke

during this stage.

Stage 3 (fully developed fire) starts when the surface of all of the combustible contents of the

room has decomposed to such an extent that sudden ignition occurs all over the room, with a

rapid and large increase in temperature (flashover).

At the end of Stage 3, the combustibles and/or oxygen have been largely consumed and

hence the temperature decreases at a rate which depends on the ventilation and the heat and

mass transfer characteristics of the system. This is known as the fire decay stage.

In each of these stages, a different mixture of decomposition products may be formed and

this, in turn, influences the corrosive potential of the fire effluent produced during that stage.

Characteristics of these fire stages are given in Table 1.

Figure 1 – Different stages in the development of a fire within a compartment

Table 1 – General classification of fires (ISO/TR 9122-1)

Oxygen * CO2/CO Temperature * Irradiance ***

Stages of fire

ratio **

°

−2

% C kW⋅m

Stage 1 Non-flaming decomposition

a) Smouldering (self-sustaining) 21 Not applicable <100 Not applicable

b) Non-flaming (oxidative) 5 to 21 Not applicable <500 <25

c) Non-flaming (pyrolytic) <5 Not applicable <1 000 Not applicable

Stage 2 Developing fire (flaming) 10 to 15 100 to 200 400 to 600 20 to 40

Stage 3 Fully developed fire (flaming)

a) Relatively low ventilation 1 to 5 <10 600 to 900 40 to 70

b) Relatively high ventilation 5 to 10 <100 600 to 1 200 50 to 150

* General environmental condition (average) within compartment.

** Mean value in fire plume near to fire.

*** Incident irradiance onto test specimen (average).

5 General aspects of the corrosivity of fire effluent

5.1 Corrosion damage scenarios

With respect to electrotechnical equipment and systems, there are three corrosion damage

scenarios which are of concern. These are where corrosion damage is caused by fire effluent

in the following situations:

a) within electrotechnical equipment and systems when exposed to fire effluent caused by

unusual, localized, internal sources of excessive heat and ignition;

b) within electrotechnical equipment and systems when exposed to fire effluent caused by

external sources of flame or excessive heat;

c) within building structures when exposed to fire effluent emitted from electrotechnical

equipment and systems.

– 14 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

Table 1 – Characteristics of fire stages (from Table 1 of ISO 19706:2011)

Max. temperature Oxygen volume

[CO]

Heat flux to

100×[CO2]

Fuel/air %

fuel surface

[CO2]

Fire stage °C % equivalence

([CO2]+[CO])

ratio (plume)

2 efficiency

kW/m Fuel surface Upper layer Entrained Exhausted v/v

1. Non-flaming

a. self-sustaining not

d

450 to 800 25 to 85 20 20 – 0,1 to 1 50 to 90

(smouldering) applicable

b. oxidative pyrolysis from

b c c

externally applied – 300 to 600 a 20 20 < 1

radiation

c. anaerobic pyrolysis from

b c c

externally applied – 100 to 500 0 0 >> 1

radiation

d e

2. Well-ventilated flaming 0 to 60 350 to 650 50 to 500 ≈ 20 ≈ 20 < 1 < 0,05 > 95

f

3. Underventilated flaming

a. small, localized fire,

a

generally in a poorly

0 to 30 300 to 600 50 to 500 15 to 20 5 to 10 > 1 0,2 to 0,4 70 to 80

ventilated compartment

g h i

b. post-flashover fire 50 to 150 350 to 650 > 600 < 15 < 5 > 1 0,1 to 0,4 70 to 90

a

The upper limit is lower than for well-ventilated flaming combustion of a given combustible.

b

The temperature in the upper layer of the fire room is most likely determined by the source of the externally applied radiation and room geometry.

c

There are few data, but for pyrolysis this ratio is expected to vary widely depending on the material chemistry and the local ventilation and thermal conditions.

d

The fire’s oxygen consumption is small compared to that in the room or the inflow, the flame tip is below the hot gas upper layer or the upper layer is not yet significantly

vitiated to increase the CO yield significantly, the flames are not truncated by contact with another object, and the burning rate is controlled by the availability of fuel.

e

The ratio can be up to an order of magnitude higher for materials that are fire-resistant. There is no significant increase in this ratio for equivalence ratios up to ≈ 0,75.

Between ≈ 0,75 and 1, some increase in this ratio may occur.

f

The fire’s oxygen demand is limited by the ventilation opening(s); the flames extend into the upper layer.

g

Assumed to be similar to well-ventilated flaming.

h

The plume equivalence ratio has not been measured; the use of a global equivalence ratio is inappropriate.

i

Instances of lower ratios have been measured. Generally, these result from secondary combustion outside the room vent.

5.2 Types of corrosion damage effects

5.2.1 Introduction

Four types of corrosion damage effect are recognized. These are

a) metal loss,

b) moving parts becoming immobile,

c) bridging of conductor circuits,

d) formation of a non-conducting layer on contact surfaces.

5.2.2 Metal loss

Metal loss is caused by oxidation of elemental metal to a positive oxidation state. One of the

simplest reactions of this type is with an acid to form a metal salt and water, and this is why

early efforts to combat potential corrosion were directed at reducing the acid gas production in

fire effluent.

However, it is not necessary for an acid to be present for oxidation to occur. If a metal is in

contact with an electrically conductive solution, the free ions of the solution can facilitate

corrosion of contacting metals by either reacting directly with the metal or by depolarizing the

area around the reacting metal. The rate of corrosion will depend on the area of metal

affected, the temperature, and on the magnitude of the difference between the electrode

potentials of the oxidizing and reducing couples. Metals higher in the electrochemical series

are more prone to corrosion.

Metal loss can cause many undesired effects. In buildings it can result in a weakening or

failure of structural elements. In electrical equipment it can cause a decrease in electrical

conductivity or ultimately the breaking of a circuit.

5.2.3 Moving parts becoming immobile

Fire effluent can cause moving parts in mechanical or electromechanical equipment to

become immobile, e.g. a ball bearing or parts in a circuit breaker. This may be because of the

deposition of sticky particulate matter or because of the formation of chemical corrosion

products between surfaces.

5.2.4 Bridging of conductor circuits

Fire effluent may contain conductive particulates, e.g. graphitic carbon or ionic species.

Metal corrosion also produces ionic species. These conductive species can bridge the small

gaps between the copper tracks on circuit boards causing undesired leakage currents. This

is of particular concern with digital telecommunications equipment.

5.2.5 Formation of a non-conducting layer on contact surfaces

This is a particular case of metal loss. Corrosion at the interface of a metal contact can result

in the formation of a layer of non-conducting material resulting in the loss of the circuit. This is

particularly likely if the contact is between dissimilar metals because they will form an

electrochemical cell when in contact with a conductive medium.

– 16 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

5.3 Factors affecting corrosivity

5.3.1 Introduction

The significant corrosion damage effects of fire effluent are assessed in terms of the rate of

functional impairment of the circuit or material affected. This impairment is dependent on a

number of factors. Some are related to the nature of the fire effluent, e.g.

– the chemical and physical nature and concentration of the fire effluent;

– interactions within the fire effluent such as smoke particulate ageing, agglomeration and

settling, condensation of liquid species, precipitation phenomena, and the absorption by

smoke particles of chemically reactive effluents.

These will in turn depend on the nature of the material being burned and on the physical fire

model being used.

Some factors are related to the corrosion environment, e.g.

– the physical and chemical nature of the affected circuits or materials;

– the prevailing conditions of temperature and relative humidity;

– the time of exposure;

– whether or not an electrical circuit is present and energized;

– post-exposure cleaning.

5.3.2 The nature of fire effluent

Many factors affect the production of fire effluent and its properties. A full description of such

properties is not possible, but the influence of several important variables is recognized.

Fire effluent is a consequence of both pyrolysis and combustion. Combustion may be

flaming or non-flaming, including smouldering, and these different modes of combustion may

produce quite different types of effluent. In pyrolysis and non-flaming combustion, volatiles

are evolved at elevated temperatures. When they mix with cool air, they condense to form

spherical droplets which appear as a light-coloured smoke aerosol. Flaming combustion

produces a black carbon-rich smoke in which the particles have a very irregular shape. The

smoke particles from flaming combustion are formed in the gas phase and in regions where

the oxygen concentrations are low enough to cause incomplete combustion. The most

abundant species in most fire effluents are carbon dioxide, water, carbon monoxide and

carbon-rich smoke.

However, many other chemicals may be present, including inorganic acids, organic acids and

ionic species. It is predominantly these last three types of material which cause fire effluent

to have a corrosive nature. The amounts of these materials which are present in fire effluent

will depend on the nature of the material being burnt and on the stage of the fire.

The heat flux on the test specimen influences how the material burns. It is good practice to

evaluate the effluent generated from materials at low levels of incident irradiance (e.g.

–2 –2 –2 –2

15 kW × m to 25 kW × m ) as well as at higher levels (e.g. 40 kW × m to 50 kW × m ).

In this way, the effects of the growth stages of a fire on the corrosive nature of the effluent

can be assessed.

The particle size distribution of smoke aerosols changes with time; smoke particles coagulate

as they age. Some properties also change with temperature so that the properties of aged, or

cold, smoke may be different from young, hot smoke. These factors may affect the way in

which smoke particles can cause short-circuits between electrical components.

5.3.3 The corrosion environment

The potential for corrosion damage can be reduced by protecting susceptible surfaces,

generally by using paint or lacquers. However, in many cases involving electrotechnical

equipment, this is not a practical solution.

The chemical nature of the exposed material will affect its susceptibility to corrosion

damage. Metals higher in the electrochemical series are more reactive. Those low in the

series such as gold and platinum are effectively inert. If dissimilar metals are in contact, one

of them will be particularly prone to corrosion because they make an electrochemical cell

when in contact with a conducting medium.

In many fire scenarios the affected materials will be at a high temperature, and temperature

has a major effect on the rate of corrosion. On average, the rate of a chemical reaction

doubles with a 10 °C K rise in temperature. The use of low heat release rate materials will

help to reduce fire temperatures and thus will reduce corrosive damage.

Relative humidity also affects corrosion reactions. Many reactions will not proceed in the

absence of water. Unfortunately, almost all fires produce water vapour as a major component

of the fire effluent so the relative humidity in the corrosion environment is likely to be high.

Also, if automatic water spray systems or fire fighters have been used, large quantities of

liquid water are likely to be present.

Two exposure times are involved. There is the time of exposure to the fire effluent when the

fire is occurring, and there is the subsequent exposure time to the prevailing conditions after

the fire has ceased. Both exposure times will affect the degree of corrosion damage. Some

reactions are auto-catalytic and therefore are initially slow but after a certain time will

progress rapidly. Also, some metals have a passive layer on their surface and again initial

reaction will be slow but when the passive layer has been removed, subsequent reaction may

be rapid.

A special problem with electrotechnical equipment is that exposed circuits may be energized.

This can cause electrochemical reactions that would not otherwise occur, and in some cases

can lead to destructive bridging or arcing phenomena.

6 Principles of corrosion damage measurement

6.1 Introduction

Corrosion damage measurement involves essentially two stages:

a) generation of the fire effluent;

b) assessment of the corrosive nature of the fire effluent.

However, each of these stages is complex and they both involve the selection of test

parameters from a wide range of possible choices.

6.2 Generation of the fire effluent

6.2.1 General

In a corrosion damage test, there are essentially two stages involved in the generation of the

fire effluent:

a) selection of the test specimen to be burned;

b) selection of an appropriate physical fire model relevant to the hazard being considered.

– 18 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 RLV © IEC 2021

6.2.2 Selection of the test specimen to be burned

Different types of test specimens may be tested. In product testing, the test specimen is a

manufactured product. In simulated product testing, the test specimen is a representative

portion of a product. The test specimen may also be a basic material (solid or liquid) or a

composite of materials.

The nature of the test specimen is governed to a large extent by the scale of the test. Small-

scale fire tests are suited more to the testing of materials and small products or

representative samples of larger products. On a larger scale, whole products may be tested.

Given a choice, it is always preferable to select a test specimen that most closely reflects its

end use.

6.2.3 Selection of the physical fire model

It is important to consider the physical fire model or models most relevant to the hazard

being assessed, and to select tests which have fire models characteristics similar to those

being assessed (see IEC TS 60695-5-2).

6.3 Assessment of corrosive potential

6.3.1 General

It is desirable that the test procedure be designed in such a manner that the results are valid

for the application of an analysis of corrosion hazard, and also as part of an analysis of total

fire hazard. Work on the design of reaction-to-fire tests to ensure that results are valid for

assessment of hazard is in its early stages (see IEC 60695-1-1 for early guidance). The

guidance in this subclause will therefore be superseded as work progresses.

There are two approaches to the assessment of the corrosive potential of fire effluent. One

involves the exposure of a specific target to the effluent, and some measurement of

impairment. In this case, the target may be an actual product or it may be a simulated

product, e.g. a test circuit or a thin sheet of metal. The other approach is indirect and involves

the measurement of certain chemical properties of the fire effluent from which the corrosive

potential may, under defined conditions, be estimated or assessed. A summary of test

methods is given in Table 2.

6.3.2 Indirect assessment

Indirect assessment involves the dissolution of a known quantity of f

...

IEC 60695-5-1 ®

Edition 3.0 2021-10

INTERNATIONAL

STANDARD

NORME

INTERNATIONALE

HORIZONTAL PUBLICATION

PUBLICATION HORIZONTALE

Fire hazard testing –

Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent – General guidance

Essais relatifs aux risques du feu –

Partie 5-1: Effets des dommages de corrosion des effluents du feu –

Recommandations générales

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from

either IEC or IEC's member National Committee in the country of the requester. If you have any questions about IEC

copyright or have an enquiry about obtaining additional rights to this publication, please contact the address below or

your local IEC member National Committee for further information.

Droits de reproduction réservés. Sauf indication contraire, aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite

ni utilisée sous quelque forme que ce soit et par aucun procédé, électronique ou mécanique, y compris la photocopie

et les microfilms, sans l'accord écrit de l'IEC ou du Comité national de l'IEC du pays du demandeur. Si vous avez des

questions sur le copyright de l'IEC ou si vous désirez obtenir des droits supplémentaires sur cette publication, utilisez

les coordonnées ci-après ou contactez le Comité national de l'IEC de votre pays de résidence.

IEC Central Office Tel.: +41 22 919 02 11

3, rue de Varembé info@iec.ch

CH-1211 Geneva 20 www.iec.ch

Switzerland

About the IEC

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is the leading global organization that prepares and publishes

International Standards for all electrical, electronic and related technologies.

About IEC publications

The technical content of IEC publications is kept under constant review by the IEC. Please make sure that you have the

latest edition, a corrigendum or an amendment might have been published.

IEC publications search - webstore.iec.ch/advsearchform IEC online collection - oc.iec.ch

The advanced search enables to find IEC publications by a Discover our powerful search engine and read freely all the

variety of criteria (reference number, text, technical publications previews. With a subscription you will always

committee, …). It also gives information on projects, replaced have access to up to date content tailored to your needs.

and withdrawn publications.

Electropedia - www.electropedia.org

IEC Just Published - webstore.iec.ch/justpublished

The world's leading online dictionary on electrotechnology,

Stay up to date on all new IEC publications. Just Published

containing more than 22 000 terminological entries in English

details all new publications released. Available online and

and French, with equivalent terms in 18 additional languages.

once a month by email.

Also known as the International Electrotechnical Vocabulary

(IEV) online.

IEC Customer Service Centre - webstore.iec.ch/csc

If you wish to give us your feedback on this publication or

need further assistance, please contact the Customer Service

Centre: sales@iec.ch.

A propos de l'IEC

La Commission Electrotechnique Internationale (IEC) est la première organisation mondiale qui élabore et publie des

Normes internationales pour tout ce qui a trait à l'électricité, à l'électronique et aux technologies apparentées.

A propos des publications IEC

Le contenu technique des publications IEC est constamment revu. Veuillez vous assurer que vous possédez l’édition la

plus récente, un corrigendum ou amendement peut avoir été publié.

Recherche de publications IEC - IEC online collection - oc.iec.ch

webstore.iec.ch/advsearchform Découvrez notre puissant moteur de recherche et consultez

La recherche avancée permet de trouver des publications IEC gratuitement tous les aperçus des publications. Avec un

en utilisant différents critères (numéro de référence, texte, abonnement, vous aurez toujours accès à un contenu à jour

comité d’études, …). Elle donne aussi des informations sur adapté à vos besoins.

les projets et les publications remplacées ou retirées.

Electropedia - www.electropedia.org

IEC Just Published - webstore.iec.ch/justpublished

Le premier dictionnaire d'électrotechnologie en ligne au

Restez informé sur les nouvelles publications IEC. Just

monde, avec plus de 22 000 articles terminologiques en

Published détaille les nouvelles publications parues.

anglais et en français, ainsi que les termes équivalents dans

Disponible en ligne et une fois par mois par email.

16 langues additionnelles. Egalement appelé Vocabulaire

Electrotechnique International (IEV) en ligne.

Service Clients - webstore.iec.ch/csc

Si vous désirez nous donner des commentaires sur cette

publication ou si vous avez des questions contactez-nous:

sales@iec.ch.

IEC 60695-5-1 ®

Edition 3.0 2021-10

INTERNATIONAL

STANDARD

NORME

INTERNATIONALE

HORIZONTAL PUBLICATION

PUBLICATION HORIZONTALE

Fire hazard testing –

Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent – General guidance

Essais relatifs aux risques du feu –

Partie 5-1: Effets des dommages de corrosion des effluents du feu –

Recommandations générales

INTERNATIONAL

ELECTROTECHNICAL

COMMISSION

COMMISSION

ELECTROTECHNIQUE

INTERNATIONALE

ICS 29.020 ISBN 978-2-8322-1011-3

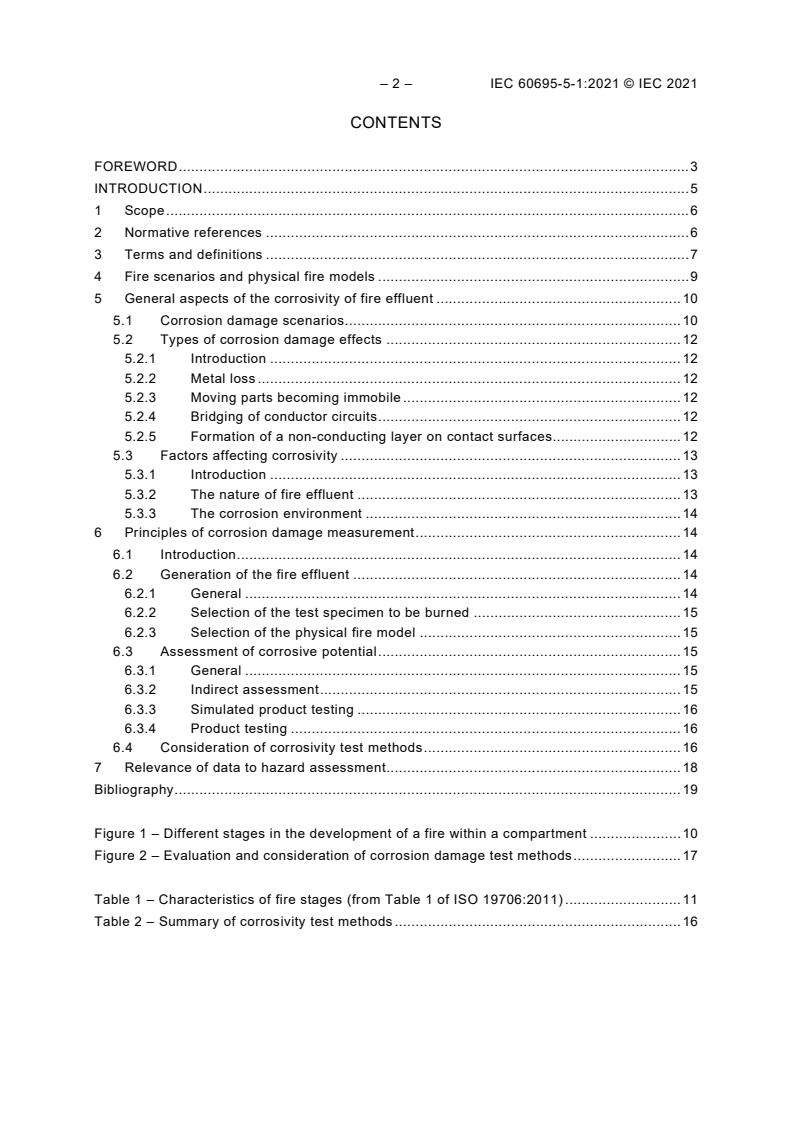

– 2 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 © IEC 2021

CONTENTS

FOREWORD . 3

INTRODUCTION . 5

1 Scope . 6

2 Normative references . 6

3 Terms and definitions . 7

4 Fire scenarios and physical fire models . 9

5 General aspects of the corrosivity of fire effluent . 10

5.1 Corrosion damage scenarios . 10

5.2 Types of corrosion damage effects . 12

5.2.1 Introduction . 12

5.2.2 Metal loss . 12

5.2.3 Moving parts becoming immobile . 12

5.2.4 Bridging of conductor circuits . 12

5.2.5 Formation of a non-conducting layer on contact surfaces. 12

5.3 Factors affecting corrosivity . 13

5.3.1 Introduction . 13

5.3.2 The nature of fire effluent . 13

5.3.3 The corrosion environment . 14

6 Principles of corrosion damage measurement . 14

6.1 Introduction . 14

6.2 Generation of the fire effluent . 14

6.2.1 General . 14

6.2.2 Selection of the test specimen to be burned . 15

6.2.3 Selection of the physical fire model . 15

6.3 Assessment of corrosive potential . 15

6.3.1 General . 15

6.3.2 Indirect assessment . 15

6.3.3 Simulated product testing . 16

6.3.4 Product testing . 16

6.4 Consideration of corrosivity test methods . 16

7 Relevance of data to hazard assessment . 18

Bibliography . 19

Figure 1 – Different stages in the development of a fire within a compartment . 10

Figure 2 – Evaluation and consideration of corrosion damage test methods . 17

Table 1 – Characteristics of fire stages (from Table 1 of ISO 19706:2011) . 11

Table 2 – Summary of corrosivity test methods . 16

INTERNATIONAL ELECTROTECHNICAL COMMISSION

____________

FIRE HAZARD TESTING –

Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent –

General guidance

FOREWORD

1) The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is a worldwide organization for standardization comprising

all national electrotechnical committees (IEC National Committees). The object of IEC is to promote

international co-operation on all questions concerning standardization in the electrical and electronic fields. To

this end and in addition to other activities, IEC publishes International Standards, Technical Specifications,

Technical Reports, Publicly Available Specifications (PAS) and Guides (hereafter referred to as “IEC

Publication(s)”). Their preparation is entrusted to technical committees; any IEC National Committee interested

in the subject dealt with may participate in this preparatory work. International, governmental and non-

governmental organizations liaising with the IEC also participate in this preparation. IEC collaborates closely

with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in accordance with conditions determined by

agreement between the two organizations.

2) The formal decisions or agreements of IEC on technical matters express, as nearly as possible, an international

consensus of opinion on the relevant subjects since each technical committee has representation from all

interested IEC National Committees.

3) IEC Publications have the form of recommendations for international use and are accepted by IEC National

Committees in that sense. While all reasonable efforts are made to ensure that the technical content of IEC

Publications is accurate, IEC cannot be held responsible for the way in which they are used or for any

misinterpretation by any end user.

4) In order to promote international uniformity, IEC National Committees undertake to apply IEC Publications

transparently to the maximum extent possible in their national and regional publications. Any divergence

between any IEC Publication and the corresponding national or regional publication shall be clearly indicated in

the latter.

5) IEC itself does not provide any attestation of conformity. Independent certification bodies provide conformity

assessment services and, in some areas, access to IEC marks of conformity. IEC is not responsible for any

services carried out by independent certification bodies.

6) All users should ensure that they have the latest edition of this publication.

7) No liability shall attach to IEC or its directors, employees, servants or agents including individual experts and

members of its technical committees and IEC National Committees for any personal injury, property damage or

other damage of any nature whatsoever, whether direct or indirect, or for costs (including legal fees) and

expenses arising out of the publication, use of, or reliance upon, this IEC Publication or any other IEC

Publications.

8) Attention is drawn to the Normative references cited in this publication. Use of the referenced publications is

indispensable for the correct application of this publication.

9) Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this IEC Publication may be the subject of

patent rights. IEC shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

International Standard IEC 60695-5-1 has been prepared by IEC technical committee 89: Fire

hazard testing.

This third edition cancels and replaces the second edition, published in 2002, and constitutes

a technical revision.

This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous

edition:

a) References to IEC TS 60695-5-3 (withdrawn in 2014) have been removed.

b) References to IEC 60695-1-1 are now to its replacements: IEC 60695-1-10 and

IEC 60695-1-11.

c) ISO/TR 9122-1 has been revised by ISO 19706.

d) Table 1 has been updated.

– 4 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 © IEC 2021

e) References to ISO 11907-2 and ISO 11907-3 have been removed.

f) Terms and definitions have been updated.

g) Text in 6.4 has been updated.

h) Bibliographic references have been updated.

The text of this International Standard is based on the following documents:

FDIS Report on voting

89/1539/FDIS 89/1543/RVD

Full information on the voting for its approval can be found in the report on voting indicated in

the above table.

The language used for the development of this International Standard is English.

This document was drafted in accordance with ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2, and developed in

accordance with ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1 and ISO/IEC Directives, IEC Supplement,

available at www.iec.ch/members_experts/refdocs. The main document types developed by

IEC are described in greater detail at www.iec.ch/standardsdev/publications.

It has the status of a basic safety publication in accordance with IEC Guide 104 and

ISO/IEC Guide 51.

In this standard, the following print types are used:

Arial bold: terms referred to in Clause 2

This standard is to be read in conjunction with IEC TS 60695-5-2.

A list of all parts in the IEC 60695 series, published under the general title Fire hazard testing,

can be found on the IEC website.

The committee has decided that the contents of this document will remain unchanged until the

stability date indicated on the IEC website under webstore.iec.ch in the data related to the

specific document. At this date, the document will be

• reconfirmed,

• withdrawn,

• replaced by a revised edition, or

• amended.

INTRODUCTION

In the design of an electrotechnical product the risk of fire and the potential hazards

associated with fire need to be considered. In this respect the objective of component, circuit

and equipment design, as well as the choice of materials, is to reduce the risk of fire to a

tolerable level even in the event of reasonably foreseeable (mis)use, malfunction or failure.

IEC 60695-1-10, IEC 60695-1-11, and IEC 60695-1-12 [1] provide guidance on how this is to

be accomplished.

Fires involving electrotechnical products can also be initiated from external non-electrical

sources. Considerations of this nature are dealt with in an overall fire hazard assessment.

The aim of the IEC 60695 series is to save lives and property by reducing the number of fires

or reducing the consequences of the fire. This can be accomplished by:

• trying to prevent ignition caused by an electrically energised component part and, in the

event of ignition, to confine any resulting fire within the bounds of the enclosure of the

electrotechnical product.

• trying to minimise flame spread beyond the product’s enclosure and to minimise the

harmful effects of fire effluents including heat, smoke, and toxic or corrosive combustion

products.

All fire effluent is corrosive to some degree and the level of potential to corrode depends on

the nature of the fire, the combination of combustible materials involved in the fire, the nature

of the substrate under attack, and the temperature and relative humidity of the environment in

which the corrosion damage is taking place. There is no evidence that fire effluent from

electrotechnical products offers greater risk of corrosion damage than the fire effluent from

other products such as furnishings or building materials.

The performance of electrical and electronic components can be adversely affected by

corrosion damage when subjected to fire effluent. A wide variety of combinations of small

quantities of effluent gases, smoke particles, moisture and temperature may provide

conditions for electrical component or system failures from breakage, overheating or shorting.

Evaluation of potential corrosion damage is particularly important for high value and safety-

related electrotechnical products and installations.

Technical committees responsible for products will choose the test(s) and specify the level of

severity.

The study of corrosion damage requires an interdisciplinary approach involving chemistry,

electricity, physics, mechanical engineering, metallurgy and electrochemistry. In the

preparation of this part of IEC 60695-5, all of the above have been considered.

IEC 60695-5-1 defines the scope of the guidance and indicates the field of application.

IEC TS 60695-5-2 provides a summary of test methods including relevance and usefulness.

___________

Numbers in square brackets refer to the bibliography.

– 6 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 © IEC 2021

FIRE HAZARD TESTING –

Part 5-1: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent –

General guidance

1 Scope

This part of IEC 60695 provides guidance on the following:

a) general aspects of corrosion damage test methods;

b) methods of measurement of corrosion damage;

c) consideration of test methods;

d) relevance of corrosion damage data to hazard assessment.

This basic safety publication is primarily intended for use by technical committees in the

preparation of standards in accordance with the principles laid down in IEC Guide 104 and

ISO/IEC Guide 51. It is not intended for use by manufacturers or certification bodies.

One of the responsibilities of a technical committee is, wherever applicable, to make use of

basic safety publications in the preparation of its publications. The requirements, test

methods or test conditions of this basic safety publication will not apply unless specifically

referred to or included in the relevant publications.

2 Normative references

The following documents are referred to in the text in such a way that some or all of their

content constitutes requirements of this document. For dated references, only the edition

cited applies. For undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including

any amendments) applies.

IEC 60695-1-10, Fire hazard testing – Part 1-10: Guidance for assessing the fire hazard of

electrotechnical products – General guidelines

IEC 60695-1-11, Fire hazard testing – Part 1-11: Guidance for assessing the fire hazard of

electrotechnical products – Fire hazard assessment

IEC TS 60695-5-2, Fire hazard testing – Part 5-2: Corrosion damage effects of fire effluent –

Summary and relevance of test methods

IEC GUIDE 104, The preparation of safety publications and the use of basic safety

publications and group safety publications

ISO/IEC Guide 51, Safety aspects – Guidelines for their inclusion in standards

ISO 11907-1:2019, Plastics – Smoke generation – Determination of the corrosivity of fire

effluents – Part 1: General concepts and applicability

ISO 13943:2017, Fire safety – Vocabulary

ISO 19706:2011, Guidelines for assessing the fire threat to people

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following

addresses:

• IEC Electropedia: available at http://www.electropedia.org/

• ISO Online browsing platform: available at http://www.iso.org/obp

3.1

corrosion damage

physical and/or chemical damage or impaired function caused by chemical action

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.69]

3.2

corrosion target

sensor used to determine the degree of corrosion damage (3.1), under specified conditions

Note 1 to entry: This sensor may be a product, a component. It may also be a reference material or object used to

simulate the behaviour of a product or a component.

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.70]

3.3

fire decay

stage of fire development after a fire has reached its maximum intensity and during which the

heat release rate and the temperature of the fire are decreasing

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.122]

3.4

fire effluent

all gases and aerosols, including suspended particles, created by combustion or

pyrolysis (3.9) and emitted to the environment

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.123]

3.5

fire scenario

qualitative description of the course of a fire with respect to time, identifying key events that

characterize the studied fire and differentiate it from other possible fires

Note 1 to entry: See fire scenario cluster (ISO 13943:2017, 3.154) and representative fire scenario

(ISO 13943:2017, 3.153).

Note 2 to entry: It typically defines the ignition and fire growth processes, the fully developed fire stage, the fire

decay (3.3) stage, and the environment and systems that will impact on the course of the fire.

Note 3 to entry: Unlike deterministic fire analysis, where fire scenarios are individually selected and used as

design fire scenarios, in fire risk assessment, fire scenarios are used as representative fire scenarios within fire

scenario clusters.

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.152]

– 8 – IEC 60695-5-1:2021 © IEC 2021

3.6

flashover

transition to a state of total surface involvement in a fire of combustible

materials within an enclosure

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.184]

3.7

full developed fire

state of total involvement of combustible materials in a fire

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.192]

3.8

leakage current

electrical current flowing in an undesired circuit

3.9

physical fire model

laboratory process, including the apparatus, the environment and the fire test procedure

intended to represent a certain phase of a fire

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.298]

3.10

pyrolysis

chemical decomposition of a substance by the action of heat

Note 1 to entry: Pyrolysis is often used to refer to a stage of fire before flaming combustion has begun.

Note 2 to entry: In fire science, no assumption is made about the presence or absence of oxygen.

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.316]

3.11

small-scale fire test

fire test performed on a test specimen of small dimensions

Note 1 to entry: There is no clear upper limit for the dimensions of the test specimen in a small-scale fire test. In

some instances, a fire test performed on a test specimen with a maximum dimension of less than 1 m is called a

small-scale fire test. However, a fire test performed on a test specimen of which the maximum dimension is

between 0,5 m and 1,0 m is often called a medium-scale fire test.

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.346]

3.12

smoke

visible part of a fire effluent

[SOURCE: ISO 13943:2017, 3.347]

4 Fire scenarios and physical fire models

During recent years, major advances have been made in the analysis of fire effluents. It is

recognized that the composition of the mixture of combustion products is particularly

dependent upon the nature of the combusting materials, the prevailing temperatures and the

ventilation conditions, especially access of oxygen to the seat of the fire. Table 1 shows how

the different stages of a fire relate to the changing atmosphere. Conditions for use in

laboratory scale tests can be derived from the table in order to correspond, as far as possible,

to full-scale fires.

Fire involves a complex and interrelated array of physical and chemical phenomena. As a

result, it is difficult to simulate all aspects of a real fire in laboratory scale apparatus. This

problem is perhaps the single most perplexing technical problem associated with all fire

testing.

General guidance for assessing the fire hazard of electrotechnical products is given in

IEC 60695-1-10. Guidance concerning fire hazard assessment is given in IEC 60695-1-11.