SIST-TP CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025

(Main)Environmentally sustainable Artificial Intelligence

Environmentally sustainable Artificial Intelligence

he proposed document will establish a framework for quantification of environmental impact of AI and its long-term sustainability, and

encourage AI developers and users to improve efficiency of AI use. It will also provide a summary of the state of the art of AI technology for direct control and optimisation of energy use in energy systems. The document will provide life-cycle assessment of AI development, deployment and use.

Emissions that are produced directly by combustion of fossil fuels are Scope 1 emissions. These are observed in transport system

and in fossil-fuel energy generators, and the like. AI may help reduce Scope 1 emissions via smart interventions (demand-side response, optimisation of combustion, etc.) Scope 2 are indirect emissions from electricity use, and AI will play a major role in reducing these emissions. Scope 3 are emissions produced during a life cycle of a technology – these emissions are important in assessment of AI solution and will be in scope of this project. Emissions of Scope 4 are the avoided emissions – AI has great potential in quantifying avoided emissions (carbon savings), and the report will address this as well.

Informationstechnik - Künstliche Intelligenz - Grüne und nachhaltige KI

Okoljsko trajnostna umetna inteligenca

Ta dokument opisuje glavna vprašanja okoljske trajnosti, ki jih organizacije ali posamezniki, ki razvijajo in/ali uporabljajo umetno inteligenco (AI), upoštevajo zlasti v kontekstu evropskih energetskih sistemov in virov.

Pomembno se je osredotočiti na uporabo umetne inteligence pri optimizaciji in virtualnem uvajanju inženirskih rešitev [1], zlasti v Evropi, z omejenimi naravnimi viri. Ta dokument preučuje evropsko področje umetne inteligence v kontekstu okoljske trajnosti. To je obravnavano s poudarkom na posebnih evropskih vidikih zahtev umetne inteligence po virih in njeni zmožnosti prispevanja k okoljski trajnosti v Evropi [2]. Dokument oblikuje pregled vplivov in tehnik za podporo okoljsko trajnostne uporabe umetne inteligence ter pravičen dostop do računalniških virov.

Predlagane izboljšave pri upravljanju virov umetne inteligence se osredotočajo na:

• zmanjšanje operativne porabe energije umetne inteligence (glej razdelek 5);

• zmanjšanje porabe drugih virov umetne inteligence (voda itd.) (glej razdelek 6).

Dokument obravnava tudi morebitne koristi uporabe umetne inteligence z vidika trajnosti. Prav tako so kvantificirane metode merjenja vplivov umetne inteligence na okoljsko trajnost.

Ta dokument je namenjen za pomoč pri pripravi novih standardov ter kot dopolnitev obstoječih evropskih standardov in standardizacijskih dokumentov, ki opredeljujejo merjenje virov za uporabo umetne inteligence. Opisuje najboljše prakse ter določa tehnike in procese upravljanja za izboljšanje učinkovitosti virov umetne inteligence in okoljske vzdržnosti. Pričakuje se, da bo dokument prispeval k prostovoljni korporativni družbeni odgovornosti (CSR) v Evropi ter izboljšal ozaveščenost posameznikov o trajnosti pri načrtovanju, razvoju in uporabi umetne inteligence. Cilj je doseči osredotočenost na odgovorno uporabo umetne inteligence, ki daje prednost etičnim vidikom, človeškim vrednotam ter razumevanju družbenih posledic razvoja in uporabe umetne inteligence.

Ta dokument je usklajen z enakovrednimi dejavnostmi v dokumentu ISO/IEC/JTC 1/SC42/WG4, TR 20226 »Zelena in trajnostna umetna inteligenca«, vendar upošteva tudi posebne vidike evropskega energetskega sistema, ki se ne uporabljajo drugje. Pri ocenjevanju ogljičnega odtisa umetne inteligence bo upoštevana zlasti trajnostna oskrba z energijo prek evropskih povezovalnih daljnovodov. Poleg tega bodo pregledane in kvantificirane rešitve umetne inteligence za optimizacijo porabe energije, da se uravnoteži poraba energije aplikacij in storitev umetne inteligence, ki uporabljajo energijo v velikem obsegu. To poročilo tudi opredeljuje in obravnava cilje trajnostnega razvoja Združenih narodov [3, 4]. Ta dokument je usklajen s standardoma ISO/IEC DIS 21031, Informacijska tehnologija – Ogljična intenzivnost programske opreme (SCI) [5] in ISO/DIS 59004, Krožno gospodarstvo – Terminologija, načela in smernice za izvajanje ter s standardom računovodstva in poročanja o emisijah toplogrednih plinov (GHG), povezanih z življenjskim ciklom izdelka [6].

Nastajajoči zakon EU o umetni inteligenci v trenutnem osnutku spodbuja prostovoljno ocenjevanje okoljske trajnosti podjetij.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Public Enquiry End Date

- 07-Jan-2025

- Publication Date

- 09-Mar-2025

- Technical Committee

- UMI - Artificial intelligence

- Current Stage

- 6060 - National Implementation/Publication (Adopted Project)

- Start Date

- 05-Mar-2025

- Due Date

- 10-May-2025

- Completion Date

- 10-Mar-2025

Overview

CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025 - "Environmentally sustainable Artificial Intelligence" - establishes a practical framework to quantify the environmental impacts and long‑term sustainability of AI across its life cycle. The technical report addresses AI energy use, non‑energy resource consumption (water, materials, land), and the potential for AI to deliver avoided emissions (carbon savings). It focuses on European energy‑system specifics (fuel mix, interconnectors, 30‑minute reporting of grid mixes) and aligns with international initiatives for green and sustainable AI.

Key Topics and Technical Requirements

- Life‑Cycle Assessment (LCA): Guidance for assessing environmental impacts across AI model development, deployment and operational use.

- Carbon and Emissions Scope: Coverage of Scope 1 (direct combustion), Scope 2 (indirect electricity), Scope 3 (life‑cycle up‑stream/down‑stream), and Scope 4 (avoided emissions) relevant to AI solutions.

- Quantification Framework: Methods to estimate AI carbon footprint and comparative efficiency metrics, including uncertainty analysis for grid fuel mixes and cross‑border power flows.

- Energy Efficiency Measures: Software, hardware and location strategies to reduce operational AI energy consumption (e.g., model optimization, efficient hardware, siting in low‑carbon grids).

- Non‑Energy Resource Impacts: Assessment and mitigation of water use, materials for hardware, land use and circular economy approaches.

- AI for Energy Optimization: Survey and summary of state‑of‑the‑art AI applications that directly control or optimize energy systems (demand response, combustion optimization, grid balancing).

- Governance and Best Practices: Recommendations for resource management, CSR, equitable access to compute, and policy guidance to reduce environmental impact.

Applications - Who Should Use This Standard

- AI developers and data scientists seeking to measure and reduce model carbon footprints.

- Cloud and data‑centre operators optimizing energy, PUE and siting decisions.

- Energy system operators and transmission system operators (TSOs) deploying AI for grid optimisation.

- Corporate sustainability and CSR teams quantifying AI‑related Scope 2/3 emissions and avoided emissions (Scope 4).

- Policymakers and regulators designing voluntary assessment frameworks and aligning with the EU AI Act.

- Standardization bodies and auditors using LCA and measurement guidance to develop complementary standards and reporting.

Related Standards and Alignment

CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025 aligns with and references international documents such as:

- ISO/IEC TR 20226 “Green and Sustainable AI” (WG4 activities)

- ISO/IEC DIS 21031 Software Carbon Intensity (SCI)

- ISO/DIS 59004 Circular Economy guidance

- Greenhouse Gas Protocol - Product Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard

Keywords: Environmentally sustainable Artificial Intelligence, green AI, AI carbon footprint, life cycle assessment, energy efficiency, Scope 1 Scope 2 Scope 3 Scope 4, European energy system, AI resource management.

Frequently Asked Questions

SIST-TP CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025 is a technical report published by the Slovenian Institute for Standardization (SIST). Its full title is "Environmentally sustainable Artificial Intelligence". This standard covers: he proposed document will establish a framework for quantification of environmental impact of AI and its long-term sustainability, and encourage AI developers and users to improve efficiency of AI use. It will also provide a summary of the state of the art of AI technology for direct control and optimisation of energy use in energy systems. The document will provide life-cycle assessment of AI development, deployment and use. Emissions that are produced directly by combustion of fossil fuels are Scope 1 emissions. These are observed in transport system and in fossil-fuel energy generators, and the like. AI may help reduce Scope 1 emissions via smart interventions (demand-side response, optimisation of combustion, etc.) Scope 2 are indirect emissions from electricity use, and AI will play a major role in reducing these emissions. Scope 3 are emissions produced during a life cycle of a technology – these emissions are important in assessment of AI solution and will be in scope of this project. Emissions of Scope 4 are the avoided emissions – AI has great potential in quantifying avoided emissions (carbon savings), and the report will address this as well.

he proposed document will establish a framework for quantification of environmental impact of AI and its long-term sustainability, and encourage AI developers and users to improve efficiency of AI use. It will also provide a summary of the state of the art of AI technology for direct control and optimisation of energy use in energy systems. The document will provide life-cycle assessment of AI development, deployment and use. Emissions that are produced directly by combustion of fossil fuels are Scope 1 emissions. These are observed in transport system and in fossil-fuel energy generators, and the like. AI may help reduce Scope 1 emissions via smart interventions (demand-side response, optimisation of combustion, etc.) Scope 2 are indirect emissions from electricity use, and AI will play a major role in reducing these emissions. Scope 3 are emissions produced during a life cycle of a technology – these emissions are important in assessment of AI solution and will be in scope of this project. Emissions of Scope 4 are the avoided emissions – AI has great potential in quantifying avoided emissions (carbon savings), and the report will address this as well.

SIST-TP CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 13.020.20 - Environmental economics. Sustainability; 35.020 - Information technology (IT) in general; 35.240.01 - Application of information technology in general. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

SIST-TP CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-april-2025

Okoljsko trajnostna umetna inteligenca

Environmentally sustainable Artificial Intelligence

Informationstechnik - Künstliche Intelligenz - Grüne und nachhaltige KI

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025

ICS:

13.020.20 Okoljska ekonomija. Environmental economics.

Trajnostnost Sustainability

35.020 Informacijska tehnika in Information technology (IT) in

tehnologija na splošno general

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

TECHNICAL REPORT CEN/CLC/TR 18145

RAPPORT TECHNIQUE

TECHNISCHER REPORT

February 2025

ICS 13.020.20; 35.240.01

English version

Environmentally sustainable Artificial Intelligence

Informationstechnik - Künstliche Intelligenz - Grüne

und nachhaltige KI

This Technical Report was approved by CEN on 10 February 2025. It has been drawn up by the Technical Committee

CEN/CLC/JTC 21.

CEN and CENELEC members are the national standards bodies and national electrotechnical committees of Austria, Belgium,

Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy,

Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia,

Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Türkiye and United Kingdom.

CEN-CENELEC Management Centre:

Rue de la Science 23, B-1040 Brussels

© 2025 CEN/CENELEC All rights of exploitation in any form and by any means

Ref. No. CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025 E

reserved worldwide for CEN national Members and for

CENELEC Members.

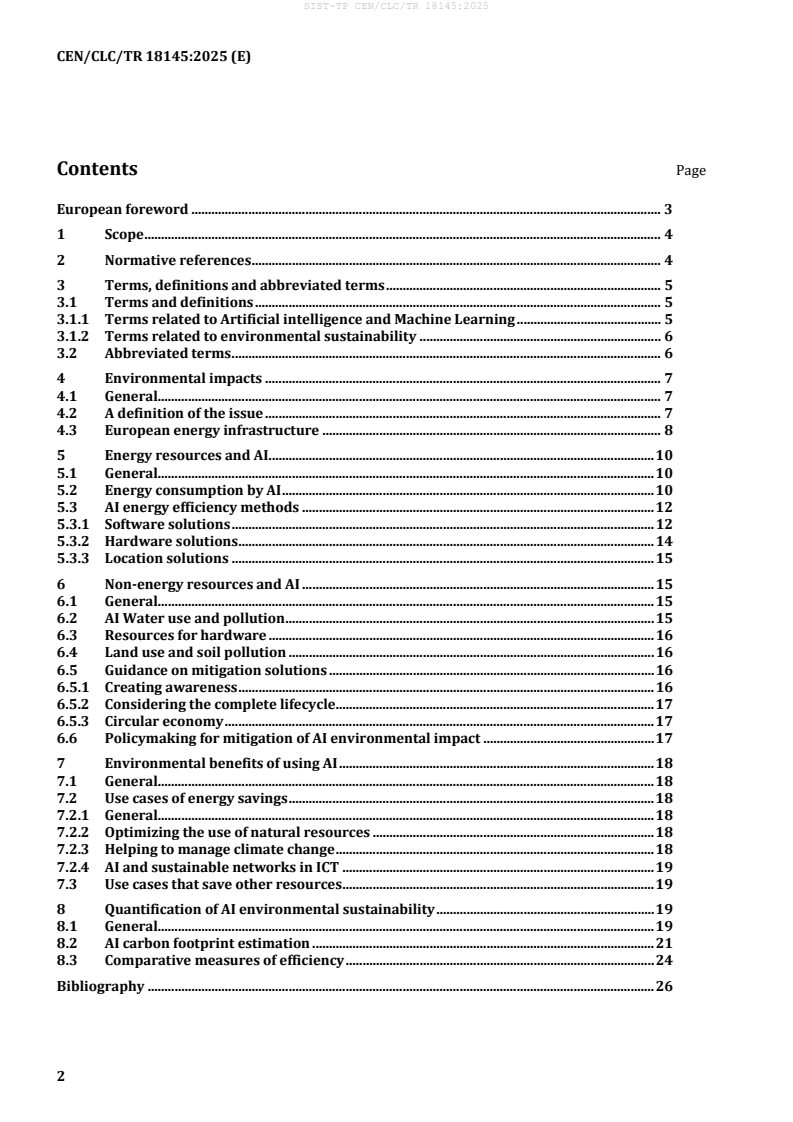

Contents Page

European foreword . 3

1 Scope . 4

2 Normative references . 4

3 Terms, definitions and abbreviated terms . 5

3.1 Terms and definitions . 5

3.1.1 Terms related to Artificial intelligence and Machine Learning . 5

3.1.2 Terms related to environmental sustainability . 6

3.2 Abbreviated terms . 6

4 Environmental impacts . 7

4.1 General. 7

4.2 A definition of the issue . 7

4.3 European energy infrastructure . 8

5 Energy resources and AI . 10

5.1 General. 10

5.2 Energy consumption by AI . 10

5.3 AI energy efficiency methods . 12

5.3.1 Software solutions . 12

5.3.2 Hardware solutions . 14

5.3.3 Location solutions . 15

6 Non-energy resources and AI . 15

6.1 General. 15

6.2 AI Water use and pollution . 15

6.3 Resources for hardware . 16

6.4 Land use and soil pollution . 16

6.5 Guidance on mitigation solutions . 16

6.5.1 Creating awareness . 16

6.5.2 Considering the complete lifecycle . 17

6.5.3 Circular economy . 17

6.6 Policymaking for mitigation of AI environmental impact . 17

7 Environmental benefits of using AI . 18

7.1 General. 18

7.2 Use cases of energy savings . 18

7.2.1 General. 18

7.2.2 Optimizing the use of natural resources . 18

7.2.3 Helping to manage climate change . 18

7.2.4 AI and sustainable networks in ICT . 19

7.3 Use cases that save other resources . 19

8 Quantification of AI environmental sustainability . 19

8.1 General. 19

8.2 AI carbon footprint estimation . 21

8.3 Comparative measures of efficiency . 24

Bibliography . 26

European foreword

This document (CEN/CLC/TR 18145:2025) has been prepared by Technical Committee CEN/CLC/JTC 21

“Artificial Intelligence”, the secretariat of which is held by DS.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. CEN shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

Any feedback and questions on this document should be directed to the users’ national standards body.

A complete listing of these bodies can be found on the CEN website.

1 Scope

This document provides a description of the main environmental sustainability issues that organisations

or individuals that are developing and/or using Artificial Intelligence (AI) consider, in particular, in the

context of the European energy systems and resources.

It is important to have a focus where AI helps in optimization and virtual deployment of engineering

solutions [1], especially in Europe with limited natural resources. This document reviews the European

AI landscape, with a context of environmental sustainability. This is addressed with a focus on European-

specific aspects of AI demands for resources, as well as its potential to contribute to environmental

sustainability in Europe [2]. The document creates an inventory of impacts and techniques to support

environmentally sustainable use of AI, and an equitable access to computation resources.

Suggested improvements in AI resource management are focused on:

• reduction of the operational AI energy consumption (see section 5)

• reduction of other AI resource consumption (water, etc.) (see section 6)

The document also considers the potential benefits of using AI from a sustainability perspective. Methods

of measuring the environmental sustainability impacts of AI are also quantified.

This document is intended to help with the development of new standards and complement existing

European standards and standardization deliverables that define resource measurement for the use of

AI. It describes best practices and indicates which techniques and management processes for

improvement of AI resource performance and environmental viability. The document is expected to

contribute to voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) in Europe, and increase sustainability

awareness for individuals when designing, developing, and using AI. The aim is to create a focus on the

responsible use of AI that prioritizes ethical considerations, human values, and an understanding of the

social implications of AI design and use.

The document is aligned with equivalent activities in ISO/IEC/JTC 1/SC42/WG4, TR 20226 “Green and

Sustainable AI”, but takes into account specific aspects of the European energy system that are not

applicable elsewhere. In particular, sustainable energy supply provided via the European interconnectors

will be taken into account when assessing AI carbon footprint. Additionally AI solutions for the

optimization of energy use will be reviewed and quantified to balance the energy use of AI applications

and services which make extensive use of energy. This report also identifies and addresses the United

Nations Sustainable Development Goals [3, 4]. Additionally, this document aligns with ISO/IEC DIS 21031

Information Technology – Software Carbon Intensity (SCI) [5], ISO/DIS 59004 Circular Economy –

Terminology, Principles and Guidance for Implementation, and the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG),

Product Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard [6].

The upcoming EU AI Act in its current draft encourages voluntary assessment of companies for

environmental sustainability.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references in this document.

3 Terms, definitions and abbreviated terms

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminology databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at https://www.iso.org/obp/

— IEC Electropedia: available at https://www.electropedia.org/

3.1 Terms and definitions

3.1.1 Terms related to Artificial intelligence and Machine Learning

3.1.1.1

artificial intelligence

AI

research and development of mechanisms and applications of AI systems

Note 1 to entry: Research and development can take place across a number of fields such as computer science, data

science, humanities, mathematics and natural sciences.

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC 22989:2022]

3.1.1.2

artificial intelligence system

AI system

engineered system that generates outputs such as content, forecasts, recommendations or decisions for

a given set of human-defined objectives

Note 1 to entry: The engineered system can use various techniques and approaches related artificial intelligence to

develop a model to represent data, knowledge, process, etc which can be used to conduct tasks.

Note 2 to entry: AI systems are designed to operate with varying levels of automation.

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC 22989:2022]

3.1.1.3

dark data

information assets that organizations collect, process and store during regular business activities, but fail

to use for purposes beyond those associated with the initial collection

3.1.1.4

internet of things

IoT

infrastructure of interconnected entities, people, systems, and information resources together with

services which processes and reacts to information from the physical world and virtual world

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC 20924:2021]

3.1.1.5

machine learning

ML

process of optimizing model parameters through computational techniques, such that the model's

behaviour reflects the data or experience

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC 22989:2022]

3.1.2 Terms related to environmental sustainability

3.1.2.1

environmental sustainability

state in which the ecosystem and its functions are maintained for the present and future generation

[SOURCE: ISO 17889-1:2021]

3.1.2.2

life cycle

evolution of a system, product, service, project or other human-made entity from conception through

retirement

[SOURCE: ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288:2015: Systems and software engineering — Software life cycle processes

Note 1 to entry: ISO/IEC 24748-1:2018 Systems and software engineering — Life cycle management — Part 1:

Guide for life cycle management and ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288:2015 Systems and software engineering — System life

cycle processes provide unified and consolidated guidance of life cycle management of systems and software

3.1.2.3

life cycle assessment

LCA

systematic evaluation of the environmental impact of a product(s) that includes all stages of its life cycle

[SOURCE: ISO 17889-2:2023]

3.1.2.4

circular economy

economic system that uses a systemic approach to maintain a circular flow of resources, by recovering,

retaining or adding to their value, while contributing to sustainable development

Note 1 to entry: The inflow of virgin resources is kept as low as possible, and the circular flow of resources is kept

as closed as possible to minimize waste, losses and releases from the economic system. Resources can be considered

concerning both stocks and flows

[SOURCE: ISO/DIS 59004]

3.2 Abbreviated terms

AI Artificial Intelligence

CPU Central Processing Unit

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility

CNN Convolutional Neural Network

DNN Deep Neural Network

ENTSO-E European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity

FFT Fast Fourier Transform

FL Federated Learning

GEMM General Matrix Multiplication

GPU Graphic Processing Unit

GWh Giga-Watt hour

GUM Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement

HDC Hyperdimensional Computing

HPC High-Performance Computing

ICT Information and Communication Technologies

IoT Internet of Things

kWh Kilowatt-hour

LCA Life-Cycle Assessment

LLM Large Language Model

ML Machine Learning

NLP Natural Language Processing

NN Neural Network

PUE Power Usage Effectiveness

PV Photovoltaic

RAM Random Access Memory

TSO Transmission System Operator

4 Environmental impacts

4.1 General

The primary environmental impact of AI (and other computer software) is the use of electricity, which is

produced in power stations using various fuels and a variety of power suppliers. Most of these resources

used by AI are from fossil fuels, such as natural gas, oil and coal.

4.2 A definition of the issue

New technologies help improve lives of European citizens and bring major benefits to society and

economy through better healthcare, more efficient public administration, safer transport, image analysis,

optimization of use of resources, a more competitive industry and sustainable agriculture.

AI is developing rapidly and requires nonlinear growth of resources such as electricity and cooling

systems consuming freshwater resources to stabilize the operational use and distributed use of resources

to serve an increasing number of cloud service users.

However, some uses of AI lead to unprecedented energy and resource impact in its life cycles, i.e. training,

deployment, and operational use.

In some European countries, such as France, majority of energy generation is nominated by nuclear fuel.

In other European countries the fuel used is more complex. With the deployment of renewable energy

sources, the complexity and intermittency of multiple types of generation are considered. The fuel mix

used for energy generation in Europe is particularly complex. National Grid operators currently report

fuel mix with a 30-min temporal resolution. The impact of cross-boundary European interconnectors,

which deliver electricity from non-European countries with different fuel mixes, also needs to be

considered. These complexities are analysed along with the associated uncertainties on fuel types to

obtain a combined uncertainty of the operational indirect carbon emissions from the power supply used

by AI. ISO/IEC Guide 98-3 – Uncertainty of Measurement – Part 3 Guide to the expression of uncertainty

in measurement [7, 8] establishes the principles and rules which are used for a broad spectrum of GUM

measurements, not just energy generation.

With broader deployment of renewable energy generation capabilities there is increasing demand for the

allocation of land and construction of the related infrastructure. Photovoltaic generation requires

substantial land mass, wind turbines are installed in offshore waters as well as in mountainous areas and

less common installations. For example, Nevada’s Ivanpah Solar Power Facility uses fields with focussing

mirrors for concentrated solar power, these can be deployed in large exclusion zones, such as deserts.

With the recent disruption of energy supplies seen in 2022, natural gas is sourced from various countries

(not necessarily in Europe), including deliveries of liquified gas by sea. Emissions from ships are direct

emissions alongside other Scope 1 transport emissions. The life cycle of all Scope 1 emissions, those

produced directly by the use of fossil fuel transport systems and energy generation, need to be included

and assessed for the estimation of carbon footprint of AI.

It is important that the life cycle assessment of hardware is included in the assessment of the carbon

footprint of AI. This will involve tracing the supply of rare earth metals, which are not currently mined in

Europe. The hardware emissions are likely to be negligible compared with the operational carbon

footprint of a large language model. It is important to note that many aspects of the life cycle assessment

often remain non-transparent. It is important that these transparency issues are noted in any emissions

assessed.

The focus of the emissions assessment on the impact of the AI corresponds to the Scope 2 indirect

emissions from operational use. These can be immediately quantified using publicly available data

supplied from European national grids. The AI carbon emissions footprint needs to be quantifiable and is

likely to be high impact to understand how AI deployment can be measured in a sustainable way. This is

the recommended approach to measure AI deployments and can be considered responsible AI.

4.3 European energy infrastructure

There are European specific aspects of energy use for AI and there are gaps in current standardization

activities which do not consider the specific energy supply. There are issues for, hydro and nuclear

generation and integrated energy systems (interconnectors). These need to be considered alongside the

United Nations sustainable development goals internationally, in Europe issues related to the delivery of

the European Green Deal, and nationally such as the UK’s Net-Zero-Carbon targets. These specific issues

introduce challenges for the assessment of carbon footprint of energy generation in quantifying the

energy mix used for energy delivery at the point of consumption, for example, at a data centre [9].

Figure 1 — Trans-European energy network ENTSO-E with major electrical interconnectors

International electrical connections are marked by blue lines, and international gas pipes by red lines,

national and minor links are denoted by grey lines. Major interconnectors are critical to understand the

cross-boundary interconnectors for energy in Europe, and the energy mix is key to assessing the energy

carbon footprint of AI use.

No other continent has such a dense interconnected network of high complex energy supply that needs

to be modelled appropriately to estimate the carbon footprint of AI energy use, specifically because

energy is imported from outside of Europe and uses different energy sources. The European Network of

Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E) is the association of the European transmission

system operators (TSOs) representing 35 countries. The synchronous grid of Europe is the largest

synchronous electrical grid (by connected power) in the world. It is an interconnected single phase-

locked 50 Hz mains frequency electricity grid that supplies over 500 million customers, most of the

European Union. The synchronous grid goals are sustainability, affordability and resilience, with a large

number of renewables integrated into many national grids [10].

Eastern European countries rely heavily on brown coal (containing lignite rather than anthracite in black

coal) for their energy supply. In France up to 75 % of electricity is generated by nuclear energy. Carbon

emissions differ depending on the fuel used and the life cycle of energy used. The energy landscape in

Europe is constantly changing, with varying suppliers, domestic and foreign, whose operational

emissions are quantified based on the publicly available data in each European country. In the UK, the

National Grid is providing 30-min fuel mix data, including interconnector data with Scandinavia, Ireland,

and France [11].

AI will be instrumental in improving energy efficiency in the European Network of Trans-European

Energy Network, optimizing energy use in demand-side response programmes, and supporting digital

energy services.

5 Energy resources and AI

5.1 General

Energy is key in the use of computer technologies, and this is particularly the case of the AI systems, as

training and deployment of neural networks can be very energy intensive. The research community is

addressing the emerging challenge of the environmental sustainability of AI with several collaboration

initiatives [12].

AI algorithms that are currently solely evaluated in terms of accuracy, in future will be judged on the

environmental impact of their complete life cycle [13, 14]. An AI system will consume energy at all stages

of its life cycle. Emissions will be created from inception, design and development, verification and

validation, deployment, operation and monitoring, continuous validation and retirement (AI system life

cycle are defined in ISO/IEC 22989:2022). At each step of the AI life cycle, energy resources are

consumed. It is essential that they are quantified, reduced where possible, optimized and efficiently used

to deliver responsible AI.

Where AI systems are using cloud service provision, processing and data handling need to be analysed

with respect to the associated cooling and energy consumed by the corresponding data centres. With

increasing use of multimedia files, in particular, images and videos of high resolution (current photo

matrices reach 45-50 megapixels), data transfer and processing become increasingly higher. Images are

often processed by cloud services without changes to the default device settings, i.e. in full resolution, one

image often reaches 10-15Mb. Contemporary standards of data handling and processing assume

automatic synchronisation of media libraries without much compression by default settings, which most

users never modify. Not only it is necessary to achieve changes to existing industry standards, but it is

also important to raise awareness with users and AI practitioners of good practices for data usage [15]

and application of AI/ML tools.

Citing the German brain researcher and biochemist Henning, “AI is also an energy-guzzling process. The

brain works with 20 watts. This is enough to cover our entire thinking ability. AI needs an incredible

amount of energy to recognize a picture of a penguin from 10 million images. To solve the problem, it

requires entire data centres that need to be kept cool., Because AI aims to reproduce brain activities but

lacks brain’s energy efficiency, we will need a vast number of nuclear power plants to provide the

necessary energy, assuming it would even be possible” [16].

In 2018 OpenAI reported that the amount of compute time used in the largest AI training runs had been

increasing exponentially, doubling every 3.4-month. This is evidenced by an analysis of OpenAI’s compute

time of the largest AI training runs. Additionally, AI is used for targeting customers’ interests online, thus

incentivizing internet browsing and streaming. Large platform companies routinely mine their databases

to address their customers with suggestions for further internet activities. According to the Shift Project

in 2019 much of this increase in compute time has been driven by online video use. This growing use of

compute time is increased by features such as default auto play and smart frame advertisements.

5.2 Energy consumption by AI

There are various side effects of electricity generation due to AI use. For example, direct and indirect

carbon emissions, air and water pollution, disposal of nuclear waste, water recycling for cooling. Amongst

these side effects indirect carbon emissions are currently the biggest social impact in the context of

climate change and require quantification for assessment of environmental sustainability of AI.

In 2015, the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) and Semiconductor Research Corporation

published a SIA report which contained a crude estimate of the future energy use required for the Internet

of Things, directly related of the number of raw bit transitions. AI applications were not considered in the

SIA 2015 report though, meaning projections of energy production was underestimated. The report did

not anticipate fast construction of power station that run on coal. In 2022 China built two new coal plants

per week to meet high energy demands. The UK is keeping open the last remaining coal power plant and

Germany has postponed the phase-out of coal as a fuel and has reactivated some coal power plants. The

SIA 2015 report stated that by 2040, digital solutions would exceed the global electric capacity, this was

without the large-scale deployment of AI experienced today in Europe and beyond.

A recent large-scale AI solution, the generative AI model called Evolved Transformer with 110 million

parameters was trained using graphics processing units (GPUs) and consumed about 656 MWh of

electricity which is equivalent to about 284 tonnes of CO emissions, the carbon footprint of a round-trip

transcontinental flight for one person [17]. Later in 2022, a group of Google researchers [18] revised

these estimates and downscaled them, due to the hardware usage and green supply of electricity at

Google. However, such flagship examples provide lower estimates of energy use, which is not average in

industry. Large language models (LLM), such as ChatGPT have require enormous amount of power,

meaning that thousands of processors are needed to both train the models and support the billions of

daily prompts created by users. Each processing unit can consume over 400 W of power while operating.

Typically, LLMs also consume a similar amount of power for cooling and power management as well. This

can lead to up to 10 gigawatt-hour (GWh) power consumption to train a single LLM such as ChatGPT-3

[19]. However, it is necessary to remember that technological development will provide more energy

efficient hardware, and consumption of energy by large models in future be compensated by lower

energy demand. The current report provides the basis for estimation of such impact in general layouts.

The number of AI solutions is growing, and it is essential that the sustainability of AI energy use influences

AI development, not least for the sustainability of the European power supply.

AI requires data, and moving data from its originating point, sensor or information source, consumes

resources. In general, the results of AI processing are smaller in size than the raw data used for the

process. It is recommended that AI processing is carried out as close as possible to the data source,

recognizing that in some cases data needs to be consolidated from several sources before it can be

processed. Solutions for processing the data as close as possible to data sources are emerging and already

available as commercial products: For example:

• Machine learning on Internet of Things (IoT) processors enabling the processing directly in

appliances such as an intelligent scale that performs body parameter analysis and learning inside the

appliance, or rotating machine vibration analysis, that performs machine learning on inexpensive

(€1) processors.

• Federated or collaborative learning where sub-models are created close to the data and consolidated

centrally by transferring the sub-models rather than the data.

• Data compression techniques that use processing to avoid precision loss when targeting artificial

intelligence processes.

Another common resource consumption factor is sensor power. Typically, IoT devices have three stages:

sleep, sense, and connect. With AI at the edge [20], the “sensing” function is associated with a sense-

making function (pattern recognition, classification, elementary transformation step from data towards

knowledge), and this additional AI-related processing will consume energy which needs to be assessed

when choosing and comparing AI strategies, for example, Edge-AI vs Cloud-AI, or Hybrid AI [21]. It is

important to consider that some commercially available edge devices combine on a single VLSI chip a

sensing layer and a pretrained neural network processing layer and therefore are considered AI at the

Edge.

The use of the Internet in general has a large carbon footprint. Electricity consumption from data centres

is 1 % of all energy demand [22], with carbon footprint ranging from 28 to 63 gCO2eq/Gb [23].

Computational load is rarely performed on a stand-alone computer, but rather operates on distributed

compute, high performance computing clusters and cloud service provision [9, 24]. This includes AI

applications, which are often resource demanding. As was shown in [17], training a single natural

language processing model can emit 284,000kg of CO , equivalent to 125 round-trip flights between New

York and Beijing.

Emissions that are produced directly by combustion of fossil fuels are Scope 1 emissions. These emissions

are created using fossil fuel transport systems and energy generation. AI will help reduce Scope 1

emissions via smart interventions (demand-side response, optimization of combustion, etc.) Scope 2 are

indirect emissions from electricity use, and AI can play a major role in reducing these emissions. Scope 3

emissions are produced during the life cycle use of technology, these emissions are important in the

assessment of emissions which would be created by an AI solution and are in the scope of this report.

Scope 4 Emissions are avoided emissions. AI has great potential for quantifying avoided emissions and

the resultant carbon savings, these are addressed in this report.

5.3 AI energy efficiency methods

5.3.1 Software solutions

The following software-based methods can help improve the carbon footprint of AI:

— Use of pre-trained modules and optimization (re-use, transfer of training algorithms)

— Use of one-for-all neural networks

— Federated learning

— Compression algorithms

— Frugal AI (using smaller data sets to train models)

— Avoidance of dark data, which is sometimes stored by organisations beyond the term of use

Software-based optimization of resources is achieved in several ways, for example by using pre-trained

modules, parallelisation, and optimal algorithms. The AI community has started to recognize their

responsibility to develop sustainable AI solutions which reduce computational load [25], such as Once-

for-all neural networks [26]. One method to address the reduction of the volume of data transfer and the

associated resource cost is federated learning (FL). This approach implements a distributed machine

learning process in which different parties collaborate to jointly train a machine learning model without

the need to share training data with the other parties [27]. This approach also has the advantage of

facilitating the application of different regulatory and privacy requirements that would apply on data

transfer, by only transferring models that do not contain such regulated information.

The large number of parameters in most of the state-of-the-art deep neural networks (DNN) make them

compute intensive, resulting in high infrastructure demands and latency [28]. Hence, it is crucial to

reduce the computational demands of DNNs to successfully meet the latency and resource requirements

of a production environment (which can be a shared resource like cloud, or a low resource system like

mobile phones). Common state-of-the-art compression mechanisms for convolutional neural networks

(CNN) include filter and weight pruning, sparsification, quantization, binarization [29], encoding, low

rank decompositions, thresholding, etc. More advanced compression techniques for BERT use

distillation, word vector elimination, and others [30, 31].

New solutions are being created to avoid training a model each time a combination of use-case or device

changes [25, 26]. These solutions design a once-for-all network that can then be configured in accordance

with the target environments and use-cases, sharing the training cost between all of the target

environments [32].

Building algorithms often consumes more resources than running them. Therefore, it makes sense to

reuse algorithms as much as possible [31]. To make more energy efficient AI systems, companies and

universities work together on an open-source basis [33] because building an AI service from scratch uses

the most data and is therefore the most energy intensive. (For more information see [34])

Energy efficient approaches are leading to the creation of Edge AI solutions, these are implemented in

some commercially available single chip systems with a sensor layer and a pretrained neural network

layer for AI processing.

During the learning phase of AI models, a large amount of data are required to achieve the best precision

possible (without over training). This is the case for example with Natural Language Programming (NLP)

where many data sets are available online, although sometimes not free and not labelled, indicating an

inequality in data accessibility. For example, in some domains edge computing where data are scarce

finding energy efficient solutions to train models could help reduce the need for data and eventually

create solutions which require reduced energy consumption.

Training of an AI model with smaller data sets which achieve precision is then transferable to algorithms

which currently require large training data sets. This is a field of research known as Frugal AI [35]. One

approach is to create a “teaching” block see the transfer-learning structure diagram below. A Frugal AI

approach would be to learn on existing models by recycling old algorithms to create new ones. This Frugal

AI approach is also known as transfer learning. The concept of transfer learning comes from the human

ability to apply previous knowledge to new situations. These techniques are already used in NLP and

computer vision, which are two data intensive domains [36].

Figure 2 — Transfer learning structure [35]

In some cases, it is possible to achieve better results using transfer learning [37] because the fine-tuning

of the hyper parameters is better when using models already trained with large data sets on a given

subject.

As energy becomes more valuable, financially and environmentally, reusing existing algorithms for AI

services could bring significant energy efficiency gains [14]. The extraction of structural relations and

features, such as the ones obtained through physical or biological modelling, reduces the need in the

system where artificial intelligence, i.e. machine learning, deep learning, reinforcement learning is still

necessary. An efficient mathematical structure of the AI implementation provides further efficiency gains,

for example Fast Fourier transformation versus classical Fourier transform, operations regularity and

simplification through a butterfly type of computation arrays, etc.

Many digital applications such as IoT sensors create large quantities of data that are stored but are often

of very little use to any application, including AI. This data uses energy when it is generated, transported,

and stored. AI systems need to avoid importing any data that is of no use. Data filtering techniques help

optimize the data that are ingested by AI systems.

Where data are to be kept long-term (for example, for compliance purposes) but is used only rarely, the

storage solutions in low energy environments and formats (such as tape or laser disks) are to be

considered.

In some circumstances using AI is not the optimal solution, or its benefits are outweighed by

environmental impacts. In these circumstances, alternative processing methods are used. This is a central

issue of circular economy and sustainability when considering the trade-offs between AI’s benefits and

negative environmental impacts. The current report provides an approach with a robust methodology

for assessment as whether the environmental negative impacts will be higher than the benefits of AI.

5.3.2 Hardware solutions

The hardware-based methods that can help improve the carbon footprint of AI:

— Reduced precision hardware and hardware accelerators

— in-memory computing methods

— neuromorphic computing

— Edge computing

— New technologies using task distribution, including optic fibre innovations.

Recently reduced precision techniques have proven exceptionally effective in accelerating deep learning

training and inference applications. The most used arithmetic function in deep learning is the dot product,

which is the building block of generalized matrix multiplication (GEMM) and convolution computations.

With current hardware architectures a dot product requires two floating-point computations requiring

accumulation inside processors. Research work verified experimentally the minimum accumulation

precision required for these computations, this is targeted to dramatically cut AI training time and cost.

Research has developed a way to enable 4-bit training of deep learning models that can be used across

many domains. Reduced accumulation bit-width requirement translates directly to a 1,5 –

2,2 × improvement in hardware energy efficiency [38].

The human brain has no separate compartments to store and compute data (“no hard drive, only RAM”),

and therefore consumes significantly less energy. Artificial Intelligence models are typically stored in off-

chip memory, and computational tasks require a constant shuffling of data between the memory and

computing units. This is a process that slows down computation and limits the maximum achievable

energy efficiency. In-memory computing methods using resistance-based memristive storage devices are

showing promising results as are non-von Neumann approaches for developing hardware that can

efficiently support AI inference models [39].

Neuromorphic computing which encompasses devices that can mimic the natural biological structures of

the human nervous system presents a promising energy efficient alternative over conventional

computing architectures [40]. High-performance computing (HDC), as an emerging computational

paradigm aims to mimic attributes of the human brain’s neuronal circuits such as hyper dimensionality,

fully distributed holographic representation, and (pseudo) randomness with the energy efficiency of

human brain [41]. This research work was performed in collaboration with ETH Zürich and was

supported in part by the European Research Council [42].

AI on Edge is low energy processor machine learning. Low energy processors with embedded machine

learning for IoT are technologies for powering devices on the edge. It brings analytics and machine

learning to the on-premises edge environment, enabling machine performance optimization, proactive

maintenance, and operational intelligence at a much lower energy cost and better efficiency. These

solutions address latency (there's no round-trip to a server), privacy (no personal data leaves the device),

connectivity (internet connectivity is not required), size (reduced model and binary size) and efficient

power consumption (efficient inference and a lack of network connections).

The European Commission will support the development of AI on Edge with dedicated testing and

experimentation facilities under the Digital Europe Programme. The Edge AI testing and experimentation

facilities aim, as a European platform, to enable companies of any size to test and experiment innovative

edge AI components based on advanced low-power computing technologies and advanced connectivity

[43, 44]. The Digital Europe Programme will also fund other testing and experimentation facilities in four

sectors (agri-food, healthcare, manufacturing, and smart cities/communities) that in part are focused on

reducing AI’s carbon footprint and/or use AI to reduce the respective sector’s carbon footprint.

Large-scale distributed training of deep neural networks on state-of-the-art platforms is expected to be

severely communication constrained and induce higher energy consumption

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...