ISO 7626-2:2015

(Main)Mechanical vibration and shock — Experimental determination of mechanical mobility — Part 2: Measurements using single-point translation excitation with an attached vibration exciter

Mechanical vibration and shock — Experimental determination of mechanical mobility — Part 2: Measurements using single-point translation excitation with an attached vibration exciter

ISO 7626-2:2015 specifies procedures for measuring linear mechanical mobility and other frequency-response functions of structures, such as buildings, machines and vehicles, using a single-point translational vibration exciter attached to the structure under test for the duration of the measurement. It is applicable to measurements of mobility, accelerance, or dynamic compliance, either as a driving-point measurement or as a transfer measurement. It also applies to the determination of the arithmetic reciprocals of those ratios, such as free effective mass. Although excitation is applied at a single point, there is no limit on the number of points at which simultaneous measurements of the motion response may be made. Multiple-response measurements are required, for example, for modal analyses.

Vibrations et chocs — Détermination expérimentale de la mobilité mécanique — Partie 2: Mesurages avec utilisation d'une excitation de translation en un seul point, au moyen d'un générateur de vibrations solidaire de ce point

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 12-Apr-2015

- Technical Committee

- ISO/TC 108 - Mechanical vibration, shock and condition monitoring

- Drafting Committee

- ISO/TC 108 - Mechanical vibration, shock and condition monitoring

- Current Stage

- 9093 - International Standard confirmed

- Start Date

- 17-Dec-2021

- Completion Date

- 12-Feb-2026

Relations

- Consolidated By

ISO 19085-9:2019 - Woodworking machines — Safety — Part 9: Circular saw benches (with and without sliding table) - Effective Date

- 06-Jun-2022

- Effective Date

- 14-Jul-2012

Overview

ISO 7626-2:2015 - part of the ISO 7626 series on mechanical vibration and shock - defines standardized procedures for experimental determination of mechanical mobility using a single-point translational vibration exciter attached to the test structure. The standard covers measurement of related frequency‑response functions (mobility, accelerance, dynamic compliance) as driving‑point or transfer measurements. Although excitation is applied at one location, simultaneous motion measurements at multiple points are supported, making the method suitable for modal analysis and multi-point dynamic characterization.

Key topics and technical requirements

- Measurement configuration: overall test-system layout, support of the structure (grounded vs ungrounded), and exciter attachment.

- Excitation methods: permitted waveforms (discretely dwelled sinusoidal, slowly swept sine, stationary random, and others) and control of excitation levels and duration.

- Vibration exciters: selection, attachment, and requirements to minimize spurious forces and moments (including transducer mass and rotational inertia effects).

- Transducer and force measurement: placement and attachment of accelerometers/velocity sensors and force transducers; procedures for mass loading and cancellation.

- Signal acquisition and processing: determination of frequency‑response functions, filtering, frequency resolution and avoidance of saturation for both sinusoidal and random excitation.

- Calibration and validation: operational calibration of sensors and amplifiers, tests for valid data (normative annex), and criteria for reliable measurements.

- Modal parameter identification: guidance (informative annex) on extracting modal properties (natural frequencies, damping ratios, mode shapes) from multiple-response mobility data.

- Supporting annexes: normative tests for validity and requirements for excitation frequency increments/durations.

Applications and users

ISO 7626-2:2015 is intended for engineers and laboratories involved in:

- Vibration testing and structural dynamics of buildings, machines, vehicles and other assemblies.

- Modal analysis, model validation and updating of finite-element models using measured mobility or accelerance data.

- Predicting dynamic interaction between interconnected components and assessing vibration transmission.

- Material dynamic property estimation and troubleshooting vibration problems in design and manufacturing.

Typical users: vibration test engineers, NVH (noise‑vibration‑harshness) specialists, structural dynamics researchers, test-house personnel and consultants.

Related standards

- ISO 7626-1 - Basic terms, definitions and transducer specifications (refer to for definitions and limitations).

- ISO 7626-5 - Measurements using impact excitation (alternative excitation method).

- ISO/TC 108 - Technical committee on mechanical vibration, shock and condition monitoring.

Keywords: ISO 7626-2:2015, mechanical mobility, vibration testing, single-point translation excitation, vibration exciter, frequency-response functions, accelerance, dynamic compliance, modal analysis.

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

BSMI (Bureau of Standards, Metrology and Inspection)

Taiwan's standards and inspection authority.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO 7626-2:2015 is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Mechanical vibration and shock — Experimental determination of mechanical mobility — Part 2: Measurements using single-point translation excitation with an attached vibration exciter". This standard covers: ISO 7626-2:2015 specifies procedures for measuring linear mechanical mobility and other frequency-response functions of structures, such as buildings, machines and vehicles, using a single-point translational vibration exciter attached to the structure under test for the duration of the measurement. It is applicable to measurements of mobility, accelerance, or dynamic compliance, either as a driving-point measurement or as a transfer measurement. It also applies to the determination of the arithmetic reciprocals of those ratios, such as free effective mass. Although excitation is applied at a single point, there is no limit on the number of points at which simultaneous measurements of the motion response may be made. Multiple-response measurements are required, for example, for modal analyses.

ISO 7626-2:2015 specifies procedures for measuring linear mechanical mobility and other frequency-response functions of structures, such as buildings, machines and vehicles, using a single-point translational vibration exciter attached to the structure under test for the duration of the measurement. It is applicable to measurements of mobility, accelerance, or dynamic compliance, either as a driving-point measurement or as a transfer measurement. It also applies to the determination of the arithmetic reciprocals of those ratios, such as free effective mass. Although excitation is applied at a single point, there is no limit on the number of points at which simultaneous measurements of the motion response may be made. Multiple-response measurements are required, for example, for modal analyses.

ISO 7626-2:2015 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 17.160 - Vibrations, shock and vibration measurements. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO 7626-2:2015 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to ISO 19085-9:2019, ISO 7626-2:1990. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

ISO 7626-2:2015 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 7626-2

Second edition

2015-04-01

Mechanical vibration and shock —

Experimental determination of

mechanical mobility —

Part 2:

Measurements using single-point

translation excitation with an attached

vibration exciter

Vibrations et chocs — Détermination expérimentale de la mobilité

mécanique —

Partie 2: Mesurages avec utilisation d’une excitation de translation en

un seul point, au moyen d’un générateur de vibrations solidaire de ce

point

Reference number

©

ISO 2015

© ISO 2015

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior

written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of

the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO 2015 – All rights reserved

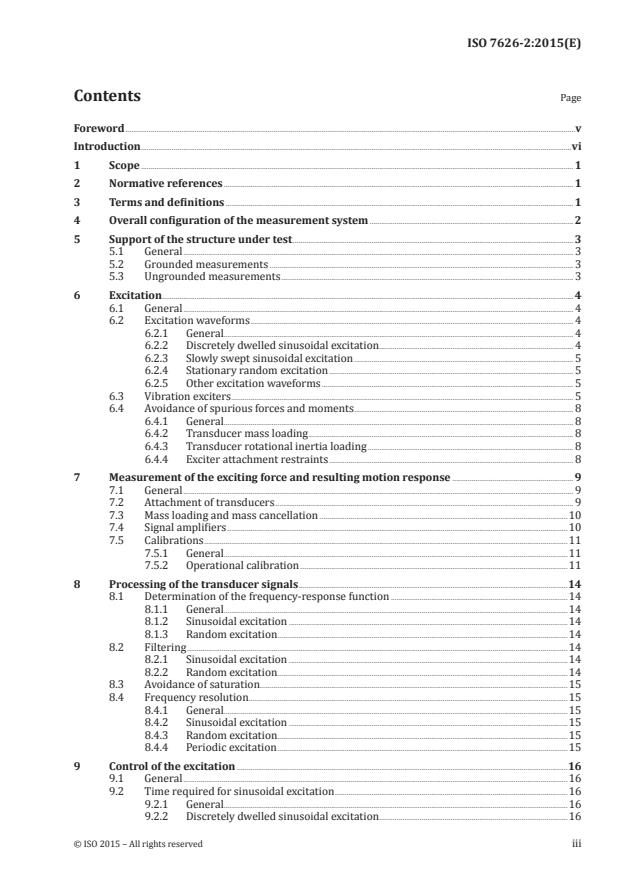

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction .vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Overall configuration of the measurement system . 2

5 Support of the structure under test . 3

5.1 General . 3

5.2 Grounded measurements . 3

5.3 Ungrounded measurements . 3

6 Excitation . 4

6.1 General . 4

6.2 Excitation waveforms . 4

6.2.1 General. 4

6.2.2 Discretely dwelled sinusoidal excitation . 4

6.2.3 Slowly swept sinusoidal excitation . 5

6.2.4 Stationary random excitation . 5

6.2.5 Other excitation waveforms . 5

6.3 Vibration exciters . 5

6.4 Avoidance of spurious forces and moments . 8

6.4.1 General. 8

6.4.2 Transducer mass loading . 8

6.4.3 Transducer rotational inertia loading . 8

6.4.4 Exciter attachment restraints . 8

7 Measurement of the exciting force and resulting motion response .9

7.1 General . 9

7.2 Attachment of transducers . 9

7.3 Mass loading and mass cancellation .10

7.4 Signal amplifiers .10

7.5 Calibrations .11

7.5.1 General.11

7.5.2 Operational calibration .11

8 Processing of the transducer signals .14

8.1 Determination of the frequency-response function .14

8.1.1 General.14

8.1.2 Sinusoidal excitation .14

8.1.3 Random excitation .14

8.2 Filtering .14

8.2.1 Sinusoidal excitation .14

8.2.2 Random excitation .14

8.3 Avoidance of saturation .15

8.4 Frequency resolution.15

8.4.1 General.15

8.4.2 Sinusoidal excitation .15

8.4.3 Random excitation .15

8.4.4 Periodic excitation .15

9 Control of the excitation .16

9.1 General .16

9.2 Time required for sinusoidal excitation .16

9.2.1 General.16

9.2.2 Discretely dwelled sinusoidal excitation .16

9.2.3 Slowly swept sinusoidal excitation .17

9.3 Time required for random excitation .17

9.4 Dynamic range.18

9.4.1 General.18

9.4.2 Sinusoidal excitation .18

9.4.3 Random excitation .18

10 Tests for valid data .18

11 Modal parameter identification .19

Annex A (normative) Tests for validity of measurement results .20

Annex B (normative) Requirements for excitation frequency increments and duration .23

Annex C (informative) Modal parameter identification .25

Bibliography .26

iv © ISO 2015 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of any

patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or on

the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation on the meaning of ISO specific terms and expressions related to conformity

assessment, as well as information about ISO’s adherence to the WTO principles in the Technical Barriers

to Trade (TBT), see the following URL: Foreword — Supplementary information.

The committee responsible for this document is ISO/TC 108, Mechanical vibration, shock and condition

monitoring.

This second edition cancels and replaces the first edition (ISO 7626-2:1990), which has been technically

revised.

ISO 7626 consists of the following parts, under the general title Mechanical vibration and shock —

Experimental determination of mechanical mobility:

— Part 1: Basic terms and definitions, and transducer specifications

— Part 2: Measurements using single-point translational excitation with an attached vibration exciter

— Part 5: Measurements using impact excitation with an exciter which is not attached to the structure

Introduction

General introduction to the ISO 7626- series on mobility measurement

Dynamic characteristics of structures can be determined as a function of frequency from mobility

measurements or measurements of the related frequency-response functions, known as accelerance and

dynamic compliance. Each of these frequency-response functions is the phasor of the motion response

at a point on a structure due to a unit force (or moment) excitation. The magnitude and the phase of

these functions are frequency-dependent.

Accelerance and dynamic compliance differ from mobility only in that the motion response is expressed

in terms of acceleration and displacement, respectively, instead of in terms of velocity. In order to

simplify the various parts of ISO 7626, only the term “mobility” is used. It is understood that all test

procedures and requirements described are also applicable to the determination of accelerance and

dynamic compliance.

Typical applications for mobility measurements are for:

a) predicting the dynamic response of structures to known or assumed input excitation;

b) determining the modal properties of a structure (natural frequencies, damping ratios and mode

shapes);

c) predicting the dynamic interaction of interconnected structures;

d) checking the validity and improving the accuracy of mathematical models of structures;

e) determining dynamic properties (i.e. the complex modulus of elasticity) of materials in pure or

composite forms.

For some applications, a complete description of the dynamic characteristics can be required using

measurements of translational forces and motions along three mutually perpendicular axes as well as

measurements of moments and rotational motions about these three axes. This set of measurements

results in a 6 × 6 mobility matrix for each location of interest. For N locations on a structure, the system

thus has an overall mobility matrix of size 6N × 6N.

For most practical applications, it is not necessary to know the entire 6N × 6N matrix. Often it is

sufficient to measure the driving-point mobility and a few transfer mobilities by exciting with a force at

a single point in a single direction and measuring the translational response motions at key points on

the structure. In other applications, only rotational mobilities might be of interest.

Mechanical mobility is defined as the frequency-response function formed by the ratio of the phasor

of the translational or rotational response velocity to the phasor of the applied force or moment

excitation. If the response is measured with an accelerometer, conversion to velocity is required to

obtain the mobility. Alternatively, the ratio of acceleration to force, known as accelerance, can be used

to characterize a structure. In other cases, dynamic compliance, the ratio of displacement to force, can

be used.

NOTE Historically, frequency-response functions of structures have often been expressed in terms of the

reciprocal of one of the above-named dynamic characteristics. The arithmetic reciprocal of mechanical mobility

has often been called mechanical impedance. It should be noted, however, that this is misleading because the

arithmetic reciprocal of mobility does not, in general, represent any of the elements of the impedance matrix of

a structure. Rather, conversion of mobility to impedance requires an inversion of the full mobility matrix. This

point is elaborated upon in ISO 7626-1.

Mobility test data cannot be used directly as part of an impedance model of the structure. In order to

achieve compatibility of the data and the model, the impedance matrix of the model is converted to

mobility or vice versa (see ISO 7626-1 for limitations).

vi © ISO 2015 – All rights reserved

Introduction to this part of ISO 7626

For many applications of mechanical mobility data, it is sufficient to determine the driving-point

mobility and a few transfer mobilities by exciting the structure at a single location in a single direction

and measuring the translational response motions at key points on the structure. The translational

excitation force can be applied either by vibration exciters attached to the structure under test or by

devices that are not attached.

Categorization of excitation devices as “attached” or “unattached” has significance in terms of the ease

of moving the excitation point to a new position. It is much easier, for example, to change the location of

an impulse applied by an instrumented hammer than it is to relocate an attached vibration exciter to a

new point on the structure. Both methods of excitation have applications to which they are best suited.

This part of ISO 7626 deals with measurements using a single attached exciter; measurements made by

impact excitation without the use of attached exciters are covered by ISO 7626-5.

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 7626-2:2015(E)

Mechanical vibration and shock — Experimental

determination of mechanical mobility —

Part 2:

Measurements using single-point translation excitation

with an attached vibration exciter

1 Scope

This part of ISO 7626 specifies procedures for measuring linear mechanical mobility and other frequency-

response functions of structures, such as buildings, machines and vehicles, using a single-point

translational vibration exciter attached to the structure under test for the duration of the measurement.

It is applicable to measurements of mobility, accelerance, or dynamic compliance, either as a driving-

point measurement or as a transfer measurement. It also applies to the determination of the arithmetic

reciprocals of those ratios, such as free effective mass. Although excitation is applied at a single point,

there is no limit on the number of points at which simultaneous measurements of the motion response

may be made. Multiple-response measurements are required, for example, for modal analyses.

2 Normative references

The following documents, in whole or in part, are normatively referenced in this document and are

indispensable for its application. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For undated

references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 2041, Mechanical vibration, shock and condition monitoring — Vocabulary

ISO 7626-1, Mechanical vibration and shock — Experimental determination of mechanical mobility —

Part 1: Basic terms and definitions, and transducer specifications

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions given in ISO 7626-1 and ISO 2041 and the

following apply.

Note As this part of ISO 7626 deals with mechanical mobility, the notes to the definitions below provide

more detail than is given in ISO 2041.

3.1

frequency-response function

frequency dependent ratio of complex motion response to complex excitation force for a linear system

Note 1 to entry: Excitation may be harmonic, random or transient functions of time. The frequency-response

function does not depend on the type of excitation function if the tested structure can be considered a linear

system in a certain range of the excitation or response. In such a case, the test results obtained with one type of

excitation may be used for estimating the response of the system to any other type of excitation. Phasors and their

equivalents for random and transient excitation are discussed in Annex B.

Note 2 to entry: Linearity of the system is a condition which, in practice, is met only approximately, depending on

the type of system and on the magnitude of the input. Care has to be taken to avoid nonlinear effects, particularly

when applying impulse excitation. Structures which are known to be nonlinear (e.g. structures with fluid

elements) should not be tested with impulse excitation and great care is required when using random excitation

for testing of such structures.

Note 3 to entry: Motion may be expressed in terms of velocity, acceleration or displacement; the corresponding

frequency response function designations are mobility, accelerance and dynamic compliance, respectively. In

some publications, these quantities are alternately referred to (in whole or in part) as mechanical admittance,

inertance and receptance, respectively. These alternate terms are avoided herein, and are provided only for

reference.

[SOURCE: ISO 2041:2009, 1.53, modified]

3.2

mobility

mechanical mobility

complex ratio of the velocity, taken at a point in a mechanical system, to the excitation force, taken at the

same or other point in the system

Note 1 to entry: Mobility is the ratio of the complex velocity-response at point i to the complex excitation force

at point j with all other measurement points on the structure allowed to respond freely without any constraints

other than those constraints which represent the normal support of the structure in its intended application.

Note 2 to entry: The term “point”, as used here, designates both a location and a direction. The terms “coordinate”

and “degree-of-freedom” have also been used with the same meaning as “point”.

Note 3 to entry: The velocity response can be either translational or rotational, and the excitation force can be

either a rectilinear force or a moment.

Note 4 to entry: If the velocity response measured is a translational one and if the excitation force applied is a

rectilinear one, the units of the mobility term are m/(N · s) in the SI system.

Note 5 to entry: Mechanical mobility is an element of the inverse of mechanical impedance matrix.

[SOURCE: ISO 2041:2009, 1.54, modified]

3.3

driving-point mobility

Y

jj

frequency-response function formed by the complex velocity-response at point j to the complex excitation

force applied at the same point with all other measurement points on the structure allowed to respond

freely without any constraint other than those constraints which represent the normal support of the

structure in its intended application

[SOURCE: ISO 2041:2009, Note to 1.55, modified]

3.4

transfer mobility

Y

ij

frequency-response function formed by the complex velocity-response at point i to the complex excitation

force applied at point j with all points on the structure, other than j, allowed to respond freely without

any constraint other than those constraints which represent the normal support of the structure in its

intended application

[SOURCE: ISO 2041:2009, 1.56, modified]

3.5

frequency range of interest

span between the lowest frequency to the highest frequency at which mobility data are to be obtained

in a given test series

[SOURCE: ISO 7626-1:2011, 3.1.5, modified]

4 Overall configuration of the measurement system

Individual components of the system used for mobility measurements carried out in accordance with

this part of ISO 7626 shall be selected to suit each particular application.

2 © ISO 2015 – All rights reserved

However, all such systems should include certain basic components arranged as shown in Figure 1.

Requirements for the characteristics and usage of those components are given in the relevant clauses.

Key

1 basic feature 8 structure under test

2 optional feature 9 motion response transducer(s)

3 signal generator 10 signal conditioners

4 power amplifier 11 monitoring oscilloscope

5 vibration exciter 12 analyser

6 drive rod 13 plotter or other output device

7 force transducer

Figure 1 — Block diagram of mobility measurement system

5 Support of the structure under test

5.1 General

Mobility measurements are performed on structures either in an ungrounded condition (freely

suspended) or in a grounded condition (attached to one or more supports), depending on the purpose

of the test. The restraints on the structure induced by the application of the vibration exciter are dealt

with in 6.4.

5.2 Grounded measurements

The support of the test structure shall be representative of its support in typical applications unless it

has been specified otherwise. A description of the support should be included in the test report.

5.3 Ungrounded measurements

A compliant suspension of the test structure shall be used. The magnitude of driving-point mobility

of the suspension at each point of attachment to the structure under test should be at least 10 times

greater than that of the structure at the same attachment point, within the frequency range of interest.

Details of the suspension system used shall be included in the test report.

In the absence of quantitative information, design of the suspension is largely a matter of judgment

depending on the frequency range of interest. As a minimum requirement, all resonance frequencies of

the rigid-body modes of the suspended structure shall be less than half the lowest frequency of interest.

Items commonly used to provide compliant suspension include shock cords and resilient pads of

material such as foam and rubber. Since some suspension systems have mass but little damping, care

shall be taken to ensure that the frequencies of the suspension resonances are well away from the

modal frequencies of the test structure itself. The masses of any suspension components, such as hooks

and turnbuckles, located close to the structure under test shall also be less than one-tenth of the free

effective mass of the structure at each frequency of interest.

Preliminary testing should be performed to identify locations for the attachment of the suspension

with the minimum possible effect on the intended measurements. Suspension near nodal points of

the structure under test will minimize the interaction of the suspension system with the structure.

Suspension cables should run normal to the direction of excitation, if practical, and even in this case,

transverse string vibrations of suspension cables can affect the data.

CAUTION — Attention should also be paid to any added damping of the structure due to the

suspension system.

6 Excitation

6.1 General

The selection of appropriate excitation depends on the particulars of the measurement application.

Factors to consider when selecting the appropriate excitation include the frequency-response and

amplitude characteristics of the exciter to be used, desired signal-to-noise ratio, available test time, and

the capabilities of the available analyser and signal-generation equipment. Prior to the advent of modern

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysers, the most common waveforms were sinusoidal. This allowed

determination of a response at a single frequency, requiring a process of stepping through the frequency

range of interest one frequency at a time. With modern FFT analysers, more complex waveforms can be

used to excite wider frequency bands to produce frequency response functions via Fourier processing

methods. Features of various types of waveforms and exciters are provided in 6.2 and 6.3.

6.2 Excitation waveforms

6.2.1 General

Applicable excitation waveforms include, but are not limited to, those described in 6.2.2 to 6.2.5. This

part of ISO 7626 reflects technology in wide use during its drafting and is not inclusive of all possible

waveforms that may be used. Comparative advantages and disadvantages of the different types of

waveforms and structures are discussed in Reference [4].

6.2.2 Discretely dwelled sinusoidal excitation

The excitation for a given measurement consists of a set of individual discrete-frequency sinusoidal

signals, applied sequentially. The frequencies of the signals are incrementally spaced over the frequency

range of interest; requirements for selecting the frequency increment are given in 9.2.2. At each

frequency, the excitation is applied over a small interval of time. The length of the time interval shall be

sufficiently long to achieve steady-state response of those natural vibration modes of the structure that

are excited at the particular frequency and to achieve proper processing of the signal.

4 © ISO 2015 – All rights reserved

6.2.3 Slowly swept sinusoidal excitation

The excitation for a given measurement is a sinusoidal signal continuously swept in frequency from the

lower to the upper limit of the frequency range of interest. The rate at which the frequency is swept shall

be slow enough to achieve quasi-steady-state response of the structure; requirements for selecting the

sweep rate are given in 9.2.3. Over a small interval of time, the energy of excitation is concentrated in

the small frequency band swept during that interval.

6.2.4 Stationary random excitation

The waveform of stationary random excitation has no explicit mathematical representation, but does

have certain statistical properties. The spectrum of the excitation signal shall be specified by the

spectral density of the exciting force. Recommendations for shaping the spectral density to concentrate

the excitation in the frequency range of interest are given in 9.4.3. All vibration modes having frequencies

within this frequency range are excited simultaneously.

6.2.5 Other excitation waveforms

6.2.5.1 General

Additional types of waveforms, described in 6.2.5.2 to 6.2.5.5, also simultaneously excite all vibration

modes within a frequency band of interest. The methods of signal processing and excitation control

used in conjunction with these waveforms are similar to those used with stationary-random excitation.

These waveforms are repetitive and are recommended when synchronous time-domain averaging of

the response waveform is necessary to measure properly the motion response of the structure.

6.2.5.2 Pseudo-random excitation

The excitation signal is synthesized digitally in the frequency domain to attain a desired spectrum

shape. An inverse Fourier transformation of the spectrum may be performed to generate repetitive

digital signals which are then converted to analogue electrical signals to drive the vibration exciter.

6.2.5.3 Periodic-chirp excitation

A periodic chirp is a rapid repetitive sweep of a sinusoidal signal in which the frequency is swept up or

down between selected frequency limits. The signal may be generated either digitally or by a sweep

oscillator and should be synchronized with the signal processor for waveform averaging to improve the

signal-to-noise ratio.

6.2.5.4 Periodic-impulse excitation

A suitably shaped impulse function, usually generated digitally, is periodically repeated. The signal

processor should be synchronized with the signal generator. The impulse function shape (typically half-

sine or decaying step functions) shall be chosen to meet the excitation frequency requirements.

6.2.5.5 Periodic-random excitation

A periodic-random excitation combines the features of stationary random and pseudo-random excitation

in that it satisfies the conditions for a periodic signal and yet changes with time so that it excites the

structure in a random manner; this is done by using different pseudo-random excitation for each average.

6.3 Vibration exciters

Devices commonly attached to the structure under test to apply input forces having desired waveforms

include electrodynamic, electrohydraulic, piezoelectric, and rotating eccentric mass vibration exciters.

The frequency ranges of general applicability for each type of exciter are shown in Figure 2.

The basic requirement of a vibration exciter is that it shall provide a sufficient force and displacement

capability so that mobility measurement can be made over the entire frequency range of interest with an

adequate signal-to-noise ratio. A vibration exciter with higher force output might be required to apply

adequate broad-band random excitation to a given structure than is needed for sinusoidal excitation.

Exciters with lower force output may be used if a band limiting of the random noise is selected or if time-

domain averaging of the excitation and response signal wave-forms is used (see 6.2.5).

NOTE The coherence function can be used as a measure of the adequacy of the vibration exciter in relation to

background and electronic noise.

The excitation-force input to a structure gives rise to a reaction force which is provided either by the

exciter support or by the inertia of the exciter itself; these approaches are illustrated in Figures 3 a)

and 3 b). If necessary, an additional mass should be attached to the exciter. An incorrect set-up which

would allow transmission of exciter reaction forces to the structure via a path other than through the

force transducer, i.e. through a common base on which both the exciter and the structure are mounted,

is illustrated in Figure 3 c).

Key

1 piezoelectric 3 electrohydraulic

2 electrodynamic 4 eccentric rotating mass

Figure 2 — Frequency ranges of typical vibration exciters

6 © ISO 2015 – All rights reserved

a) Reaction by external support b) Reaction by exciter inertia

c) Reaction by excited structure: undesirable

Key

1 structure suspension 3 exciter suspension

2 exciter support

Figure 3 — Reactions of exciter

6.4 Avoidance of spurious forces and moments

6.4.1 General

For translational mobility measurements, it is required that the excitation force be applied only along

the intended direction at the points of interest on a structure.

Any spurious moment or force (other than that along the intended direction) will cause errors in the

resulting mobility data. The driving point and all measurement points on the structure shall be free to

respond by moving in any direction without restraint. Dynamic interactions between the structure and

the motion and force transducers as well as between the structure and the exciter shall be avoided. In

order to ensure that spurious forces and moments be avoided the factors dealt with in 6.4.2 to 6.4.4 shall

be taken into consideration.

6.4.2 Transducer mass loading

Spurious forces are generated at each transducer attachment point as a result of the acceleration of

the transducer mass. Measurement errors caused by mass loading shall be minimized by selecting

transducers having the smallest mass consistent with sensitivity requirements. When measuring

driving-point mobility, such loading by a force transducer can be electronically compensated to a certain

extent (see 7.3).

6.4.3 Transducer rotational inertia loading

Spurious moments are generated at each transducer attachment point as a result of the rotational

acceleration of the transducer, especially impedance heads which may have a large rotational inertia.

Such spurious moments shall be minimized by selecting transducers having low moments of inertia

about their mounting points.

6.4.4 Exciter attachment restraints

Spurious moments and cross-axis forces are generated at the exciter attachment point by restraints

imposed on the rotational and lateral driving-point responses of the structure under test. For example,

clamping constraints introduced by the exciter/impedance head assembly could adversely affect the

measurement of low-order modes in test structures. The use of area-reducing cones may be required to

approximate more closely a point driving force.

NOTE 1 Area-reducing cones can further increase the likelihood of introducing a spurious moment if careful

consideration is not given to their use.

Avoidance of exciter attachment restraints is often the most difficult problem encountered when using

fixed vibration exciters to measure the mobility of lightweight structures.

To avoid measurement errors caused by attachment restraints, the magnitudes of the lateral and

rotational driving-point mobilities of the exciter attachment, when the exciter and attachment hardware

are disconnected from the structure, shall be at least ten times larger, at all frequencies of interest, than

those of the corresponding elements of the driving-point mobility matrix of the structure itself.

In the absence of quantitative data for either lateral or rotational driving-point mobility, determination of

whether a particular test set-up avoids measurement errors caused by significant attachment restraints

is often a matter of judgment. The following items shall be taken into consideration:

a) the use of a free-floating voice-coil exciter as in Reference [5];

b) the design of the support system for an inertia-controlled exciter such that the reaction to the force

applied to the structure under test will not result in any rotational motion of the exciter nor in any

motion transverse to the axis of the force transducers;

c) the installation of a drive rod connecting the exciter to the force transducers.

8 © ISO 2015 – All rights reserved

[6]

The drive rod shall be designed to provide a high stiffness in the axial direction and sufficient flexibility

in all other directions. Slender short rods are frequently used for this purpose; however, thick rods with

thin flexible sections near each end may give better results. Care shall be taken to ensure that the exciter

and drive rod are aligned with the force transducer axis.

If flexible drive rods are used, the accelerometer shall be attached directly to the structure in all cases.

The accelerometer shall not be connected to the structure via intermediate devices, such as drive rods,

the axial compliance of which would render motion-response measurements invalid [see Figure 4 a)].

The force transducer shall be arranged so that it always measures the force transmitted from the drive

rod to the structure [see Figure 4 b)]. Only with extreme caution can the force transducer be located at

the exciter end of the rod [see Figure 4 c)]. If the arrangement illustrated in Figure 4 c) is unavoidable,

the effect of the drive rod compliance shall be checked as described in ISO 7626-1 and the compensation

for the rod mass shall be applied using the procedure specified in 7.3.

NOTE 2 Drive-rod bending modes having natural frequencies within the frequency range of interest might

interfere with the mobility test. Furthermore, bending vibrations of the moving systems of the exciter might

introduce moments into the structure, which are not detected by the force transducer, but can affect the response

measurements.

7 Measurement of the exciting force and resulting motion response

7.1 General

Basic criteria and requirements for the selection of motion transducers, force transducers and impedance

heads, and methods for determining the characteristics of those transducers are specified in ISO 7626-1.

Measurements of exciter current or voltage shall not be used to infer excitation force amplitudes without

calibration by taking all factors (masses, friction, etc). Preferably, excitation forces shall be measured by

a suitable transducer.

The types of transducers most commonly used in structural frequency-response measurements are

piezoelectric accelerometers, piezoelectric force transducers, and impedance heads combining those

devices in one assembly. Displacement or velocity transducers may be used in lieu of accelerometers. Some

displacement transducers offer the advantage of a non-contacting design. Piezo-resistive accelerometers

have certain advantages when impulsive excitation waveforms are used. Care shall be taken to ensure

that the frequency response and linear range of any candidate transducer are sufficiently broad and

the base strain sensitivity of the accelerometers is sufficiently low to avoid any misinterpretation of the

signals.

Any of the three types of motion (displacement, velocity and acceleration) may be determined using

any type of motion transducer by multiplying the measurement result, at each frequency f, using the

following factor raised to the appropriate positive or negative integer exponent:

n

jf2π (1)

()

where

j=−1 , f is the frequency concerned, the integer exponent n = −2 for acceleration measurement to

displacement presentation, n = −1 for acceleration to velocity or velocity to displacement, n = 1 for

displacement to velocity or velocity to acceleration, and n = 2 for displacement to acceleration.

7.2 Attachment of transducers

Two methods commonly used to attach force and motion transducers to structures are threaded

studs and cement; detailed guidance on transducer attachment methods is given in ISO 5348 and

References [7],

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...