ISO 1100-2:1998

(Main)Measurement of liquid flow in open channels — Part 2: Determination of the stage-discharge relation

Measurement of liquid flow in open channels — Part 2: Determination of the stage-discharge relation

Mesurage de débit des liquides dans les canaux découverts — Partie 2: Détermination de la relation hauteur-débit

General Information

- Status

- Withdrawn

- Publication Date

- 06-May-1998

- Withdrawal Date

- 06-May-1998

- Technical Committee

- ISO/TC 113/SC 1 - Velocity area methods

- Drafting Committee

- ISO/TC 113/SC 1 - Velocity area methods

- Current Stage

- 9599 - Withdrawal of International Standard

- Start Date

- 15-Nov-2010

- Completion Date

- 14-Feb-2026

Relations

- Effective Date

- 15-Apr-2008

- Effective Date

- 15-Apr-2008

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

BSMI (Bureau of Standards, Metrology and Inspection)

Taiwan's standards and inspection authority.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO 1100-2:1998 is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Measurement of liquid flow in open channels — Part 2: Determination of the stage-discharge relation". This standard covers: Measurement of liquid flow in open channels — Part 2: Determination of the stage-discharge relation

Measurement of liquid flow in open channels — Part 2: Determination of the stage-discharge relation

ISO 1100-2:1998 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 17.120.20 - Flow in open channels. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO 1100-2:1998 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to ISO 1100-2:1982, ISO 1100-2:2010. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

ISO 1100-2:1998 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 1100-2

Second edition

1998-05-01

Measurement of liquid flow in open

channels —

Part 2:

Determination of the stage-discharge relation

Mesurage de débit des liquides dans les canaux découverts —

Partie 2: Détermination de la relation hauteur-débit

A

Reference number

©

ISO

Contents

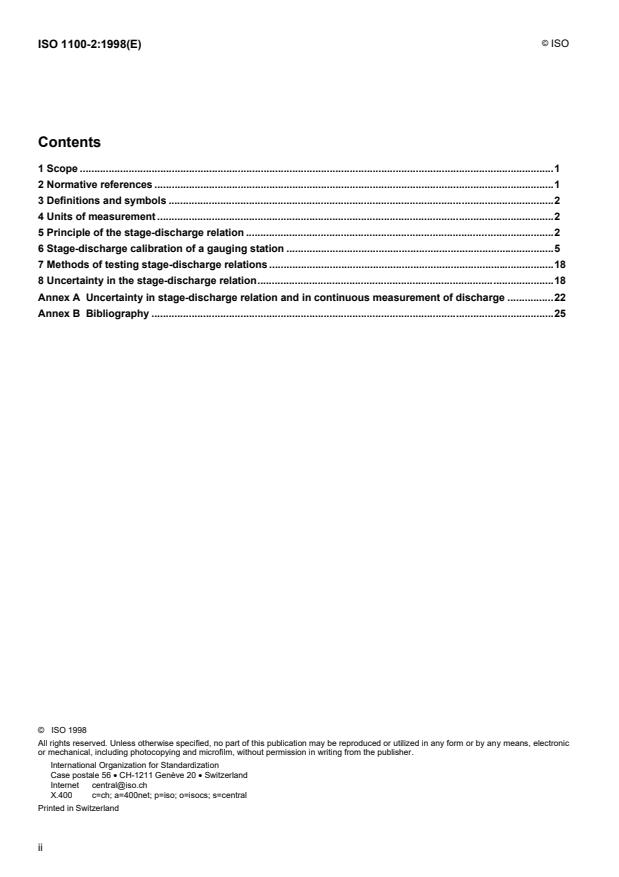

1 Scope .1

2 Normative references .1

3 Definitions and symbols .2

4 Units of measurement .2

5 Principle of the stage-discharge relation .2

6 Stage-discharge calibration of a gauging station .5

7 Methods of testing stage-discharge relations .18

8 Uncertainty in the stage-discharge relation.18

Annex A Uncertainty in stage-discharge relation and in continuous measurement of discharge .22

Annex B Bibliography .25

© ISO 1998

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from the publisher.

International Organization for Standardization

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Genève 20 • Switzerland

Internet central@iso.ch

X.400 c=ch; a=400net; p=iso; o=isocs; s=central

Printed in Switzerland

ii

©

ISO ISO 1100-2:1998(E)

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies

(ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through ISO technical

committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical committee has been established has

the right to be represented on that committee. International organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in

liaison with ISO, also take part in the work. ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical

Commission (IEC) on all matters of electrotechnical standardization.

Draft International Standards adopted by the technical committees are circulated to the member bodies for voting.

Publication as an International Standard requires approval by at least 75 % of the member bodies casting a vote.

International Standard ISO 1100-2 was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 113, Hydrometric determinations,

Subcommittee SC 1,

Velocity-area methods.

This second edition cancels and replaces the first edition (ISO 1100-2:1982), which has been technically revised.

Annexes A and B of this part of ISO 1100 are for information only.

iii

©

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO ISO 1100-2:1998(E)

Measurement of liquid flow in open channels —

Part 2:

Determination of the stage-discharge relation

1 Scope

This part of ISO 1100 specifies methods of determining the stage-discharge relation for a gauging station. A

sufficient number of discharge measurements, complete with corresponding stage measurements, is required to

define a stage-discharge relation to the accuracy required by this part of ISO 1100.

Stable and unstable channels are considered, including brief descriptions of the effects on the stage-discharge

relation of ice and hysteresis. Methods for determining discharge for twin-gauge stations, ultrasonic velocity

stations, electromagnetic velocity stations, and other complex ratings are not described in detail. These types of

rating are described in other International Standards and Technical Reports, namely ISO/TR 9123, ISO 6416 and

ISO 9213, as shown in clause 2.

2 Normative references

The following standards contain provisions which, through reference in this text, constitute provisions of this part of

ISO 1100. At the time of publication, the editions indicated were valid. All standards are subject to revision, and

parties to agreements based on this part of ISO 1100 are encouraged to investigate the possibility of applying the

most recent editions of the standards indicated below. Members of IEC and ISO maintain registers of currently valid

International Standards.

ISO 31:1992 (all parts), Quantities, units and symbols.

ISO 772:1996, Hydrometric determinations — Vocabulary and symbols.

ISO 1000:1992, SI units and recommendations for the use of their multiples and of certain other units.

1)

ISO/TR 5168: – , Measurement of fluid flow — Evaluation of uncertainties.

ISO 6416:1992, Liquid flow measurement in open channels — Measurement of discharge by the ultrasonic

(acoustic) method.

ISO/TR 9123:1986, Liquid flow measurement in open channels — Stage-fall-discharge relations.

ISO 9196:1992, .

Liquid flow measurement in open channels — Flow measurements under ice conditions

ISO 9213:1992, Measurement of total discharge in open channels — Electromagnetic method using a full-channel-

width coil.

1)

To be published. (Revision of ISO 5168:1978)

©

3 Definitions and symbols

For the purpose of this part of ISO 1100, the definitions and symbols given in ISO 772 apply. Those that are not

covered by ISO 772 are given in the text of this part of ISO 1100. The symbols used in this part of ISO 1100 are

given below:

A cross-sectional area,

C a coefficient of discharge,

D

C Chezy's channel rugosity coefficient,

h gauge height of the water surface,

b slope of the rating curve,

Q total discharge,

Q steady-state discharge,

o

r hydraulic radius, equal to the effective cross-sectional area divided by the wetted perimeter (A/P)

h

S friction slope,

f

S water surface slope corresponding to steady discharge,

o

velocity of a flood wave,

v

w

B cross-section width,

e effective gauge height of zero flow,

H total head (hydraulic head),

is Manning's channel rugosity coefficient,

n

p is a constant that is numerically equal to the discharge when the effective depth of flow (h 2 e) is equal

to 1,

t is time.

4 Units of measurement

The International System of Units (SI Units) is used in this part of ISO 1100 in accordance with ISO 31 and ISO

1000.

5 Principle of the stage-discharge relation

The stage-discharge relation is the relation at a gauging station between stage and discharge, and is sometimes

referred to as a rating or rating curve. The principles of the establishment and operation of a gauging station are

described in ISO 1100-1.

©

ISO

5.1 Controls

5.1.1 General

The stage-discharge relation for open-channel flow at a gauging station is governed by channel conditions

downstream from the gauge, referred to as a control. Two types of control can exist, depending on channel and flow

conditions. Low flows are usually controlled by a section control, whereas high flows are usually controlled by a

channel control. Medium flows may be controlled by either type of control. At some stages, a combination of section

and channel control may occur. These are general rules and exceptions can and do occur. Knowledge of the

channel features that control the stage-discharge relation is important. The development of stage-discharge curves

where more than one control is effective, where control features change, and where the number of measurements

is limited, usually requires judgement in interpolating between measurements and in extrapolating beyond the

highest or lowest measurements. This is particularly true where the controls are not permanent and tend to shift

from time to time, resuIting in changes in the positioning of segments of the stage-discharge relation.

Controls and their governing equations are described in the following clauses.

5.1.2 Section control

A section control is a specific cross-section of a stream channel, located downstream from a water-level gauge, that

controls the relation between gauge height and discharge at the gauge. A section control can be a natural feature

such as a rock ledge, a sand bar, a severe constriction in the channel, or an accumulation of debris. Likewise, a

section control can be a manmade feature such as a small dam, a weir, a flume, or an overflow spillway. Section

controls can frequently be visually identified in the field by observing a riffle, or pronounced drop in the water

surface, as the flow passes over the control. Frequently, as gauge height increases because of higher flows, the

section control will become submerged to the extent that it no longer controls the relation between gauge height and

discharge. At this point, the riffle is no longer observable, and flow is then regulated either by another section control

further downstream, or by the hydraulic geometry and roughness of the channel downstream (i.e. channel control).

5.1.3 Channel control

A channel control consists of a combination of features throughout a reach downstream from a gauge. These

features include channel size, shape, curvature, slope, and rugosity. The length of channel reach that controls a

stage-discharge relation varies. The stage-discharge relation for relatively steep channels may be controlled by a

relatively short channel reach, whereas, the relation for a relatively flat channel may be controlled by a much longer

channel reach. In addition, the length of a channel control will vary depending on the magnitude of flow. Precise

definition of the length of a channel-control reach is usually neither possible nor necessary.

5.1.4 Combination controls

At some stages, the stage-discharge relation may be governed by a combination of section and channel controls.

This usually occurs for a short range in stage between section-controlled and channel-controlled segments of the

rating. This part of the rating is commonly referred to as a transition zone of the rating, and represents the change

from section control to channel control. In other instances, a combination control may consist of two section

controls, where each has partial controlling effect. More than two controls acting simultaneously is rare. In any case,

combination controls, and/or transition zones, occur for very limited parts of a stage-discharge relation and can

usually be defined by plotting procedures. Transition zones in particular represent changes in the slope or shape of

a stage-discharge relation.

5.2 Governing hydraulic equations

Stage-discharge relations are hydraulic relations that can be defined according to the type of control that exists.

Section controls, either natural or manmade, are governed by some form of the weir or flume equations. In a very

general and basic form, these equations are expressed as:

1,5

Q = C BH (1)

D

©

where

Q is discharge, in cubic metres per second (m /s),

C is a coefficient of discharge and may include several factors,

D

B is cross-section width, in metres (m), and

H is hydraulic head, in metres.

Stage-discharge relations for channel controls with uniform flow are governed by the Manning or Chezy equation,

as it applies to the reach of controlling channel downstream from a gauge. The Manning equation is:

0,67 0,5

A r S

h f

Q = (2)

n

where

A is cross-section area, in square metres,

r is hydraulic radius, in metres,

h

S is friction slope, and

f

n is channel rugosity.

The Chezy equation is:

0,50 0,50

Q = C A r S (3)

h f

where C is the Chezy form of rugosity.

The above equations are generally applicable for gradually varied, uniform flow. For highly varied, nonuniform flow,

equations such as the Saint-Venant unsteady flow equations would be appropriate. However, these are seldom

used in the development of stage-discharge relations, and are not described in this part of ISO 1100.

5.3 Complexities of stage-discharge relations

Stage-discharge relations for stable controls such as a rock outcrop, and manmade structures such as weirs,

flumes, and small dams usually present few problems in their calibration and maintenance. However, complexities

can arise when controls are not stable and/or when variable backwater occurs. For unstable controls, segments of a

stage-discharge relation may change position occasionally, or even frequently. This is usually a temporary condition

which can be accounted for through the use of the shifting-control method.

Variable backwater can affect a stage-discharge relation, both for stable and unstable channels. Sources of

backwater can be downstream reservoirs, tributaries, tides, ice, dams and other obstructions that influence the flow

at the gauging station control.

Another complexity that exists for some streams is hysteresis, which results when the water surface slope changes

due to either rapidly rising or rapidly falling water levels in a channel control reach. Hysteresis is sometimes referred

to as loop ratings, and is most pronounced in relatively flat sloped streams. On rising stages the water surface slope

is significantly steeper than for steady flow conditions, resulting in greater discharge than indicated by the steady

flow rating. The reverse is true for falling stages. See 6.8.4 for details on hysteresis ratings.

The succeeding clauses of this part of ISO 1100 will describe in more detail some of the techniques available for

analyzing the various complexities that may arise.

©

ISO

6 Stage-discharge calibration of a gauging station

6.1 General

The primary object of a stage-discharge gauging station is to provide a record of the discharge of the open channel

or river at which the water lever gauge is sited. This is achieved by measuring the stage and converting this stage to

discharge by means of a stage-discharge relation, which correlates discharge and water level. In some instances,

other parameters such as index velocity, water surface fall between two gauges, or rate-of-change in stage may

also be used in rating calibrations. Stage-discharge relations are usually calibrated by measuring discharge and the

corresponding gauge height. Theoretical computations may also be used to aid in the shaping and positioning of the

rating curve. Stage-discharge relations from previous time periods should also be considered as an aid in the

shaping of the rating.

6.2 General preparation of a stage-discharge relation

6.2.1 General

The relation between stage and discharge is defined by plotting measurements of discharge with corresponding

observations of stage, taking into account whether the discharge is steady, increasing or decreasing, and also

noting the rate of change in stage. This may be done manually by plotting on paper, or by using computerized

plotting techniques. A choice of two types of plotting scale is available, either an arithmetic scale or a logarithmic

scale. Each has certain advantages and disadvantages, as explained in subsequent clauses. It is customary to plot

the stage as ordinate and the discharge as abscissa, although when using the stage-discharge relation to derive

discharge from a measured value of stage, the stage is treated as the independent variable.

6.2.2 List of discharge measurements

The first step before making a plot of stage versus discharge is to prepare a list of discharge measurements that will

be used for the plot. At a minimum this list should include at least 12 to 15 measurements, all made during the

period of analysis. These measurements should be well distributed over the range in gauge heights experienced. It

should also include low and high measurements from other times that might be useful in defining the correct shape

of the rating and/or for extrapolating the rating. Extreme low and high measurements should be included wherever

possible.

For each discharge measurement in the list the following items shall be included:

a) Unique identification number

b) Date of measurement

c) Gauge height of measurement

d) Total discharge

e) Accuracy of measurement

f) Rate-of-change in stage during measurement, a plus sign indicating rising stage and a minus sign indicating

falling stage.

Other information might be included in the list of measurements, but is not mandatory. Table 1 shows a typical list of

discharge measurements, including a number of items in addition to the mandatory items. The discharge

measurement list may be handwritten for use when hand-plotting is done, or the data may be a computer list where

a computerized plot is developed.

©

Table 1 — Typical list of discharge measurements

ID Date Width Area Mean Gauge Effective Number Gauge

Made Discharge Method Rated

number velocity height depth verticals height

by

change

m m m/s m m m/h

m /s

12 04/08/38 MEF 36,27 77,94 1,272 2,682 2,082 99,12 0,2/0,8 22 –0,082 GOOD

183 02/06/55 GTC 33,53 78,41 1,405 2,786 2,186 110,2 0,6/0,2/0,8 22 –0,047 GOOD

201 02/04/57 AJB 28,96 21,92 1,511 2,002 1,402 33,13 0,6/0,2/0,8 21 –0,013 POOR

260 03/13/63 GMP 26,52 21,46 1,400 1,981 1,381 30,02 0,6 22 –0,020 GOOD

313 08/24/66 HFR 30,18 42,08 1,602 2,374 1,774 67,40 0,6/0,2/0,8 22 +0,006 GOOD

366 08/21/73 MAF 28,96 14,86 0,476 1,557 0,957 7,080 0,6 21 0 GOOD

367 10/10/73 MAF 28,96 13,66 0,361 1,490 0,890 4,928 0,6 21 0 GOOD

368 11/26/73 MAF 29,26 14,21 0,373 1,509 0,909 5,296 0,6 18 0 GOOD

369 02/19/74 MAF 29,87 16,26 1,291 1,838 1,238 20,99 0,6 21 0 GOOD

370 04/09/74 MAF 29,26 21,27 0,805 1,780 1,180 17,13 0,6/0,2/0,8 21 0 GOOD

371 05/29/74 MAF 29,57 19,69 0,688 1,710 1,110 13,54 0,6 21 0 GOOD

372 07/10/74 MAF 28,96 16,81 0,458 1,573 0,973 7,703 0,6 21 0 GOOD

373 08/22/74 MAF 29,26 15,79 0,481 1,570 0,970 7,590 0,6 21 0 GOOD

374 10/01/74 MAF 29,26 13,19 0,264 1,414 0,814 3,483 0,6 21 0 GOOD

375 11/11/74 MAJ 28,96 11,71 0,283 1,396 0,796 3,313 0,6 21 0 GOOD

382 10/01/75 MAF 30,48 43,76 1,598 2,432 1,832 69,95 0,2/0,8 21 +0,017 GOOD

6.2.3 Arithmetic plotting scales

The simplest type out measurements shown in figure 1. Scale subdivisions should be chosen to cover the complete

range of gauge height and discharge expected to occur at the gauging site. Scales should be subdivided in uniform,

even increments that are easy to read and interpolate. They should also be chosen to produce a rating curve that is

not unduly steep or flat. Usually the curve should follow a slope of between 30° and 50°. If the range in gauge height

or discharge is large, it may be necessary to plot the rating curve in two or more segments to provide scales that

are easily read with the necessary precision. This procedure may result in separate curves for low water, medium

water, and high water. Care should be taken to see that, when joined, the separate curves form a smooth,

continuous combined curve.

Graph paper with arithmetic scales is convenient to use and easy to read. Such scales are ideal for displaying a

rating curve, and have an advantage over logarithmic scales, in that zero values of gauge height and/or discharge

can be plotted. However, for analytical purposes, arithmetic scales have practically no advantage. A stage-

discharge relation on arithmetic scales is almost always a curved line, concave downward, which can be difficult to

shape correctly if only a few discharge measurements are available. Logarithmic scales, on the other hand, have a

number of analytical advantages as described in the next clause. Generally, a stage-discharge relation is first drawn

on logarithmic plotting paper for shaping and analytical purposes, and then later transferred to arithmetic plotting

paper if a display plot is needed.

6.2.4 Logarithmic plotting scales

Most stage-discharge relations, or segments thereof, are best analyzed graphically through the use of logarithmic

plotting paper. To utilize fully this procedure, gauge height should be transformed to effective depth of flow on the

control by subtracting from it the effective gauge height of zero discharge. A rating curve segment for a given

control will then tend to plot as a straight line with an equation form as described in 6.2.4.2. The slope of the straight

line will conform to the type of control (section or channel), thereby providing valuable information to shape correctly

©

ISO

the rating curve segment. In addition, this feature allows the analyst to calibrate the stage-discharge relation with

fewer discharge measurements. The slope of a rating curve is the ratio of the horizontal distance to the vertical

distance. This non-standard way of measuring slope is necessary because the dependent variable (discharge) is

always plotted as the abscissa.

NOTE — Numbers indicated against plotted observations refer to ID numbers given in table 1.

Figure 1 — Arithmetic plot of stage-discharge relation

Rating curves for section controls such as a weir or flume conform to equation (1), and when plotted logarithmically

the slope will be 1,5 or greater depending on control shape, velocity of approach, and minor variations of the

coefficient of discharge. Logarithmic rating curves for most weir shapes will plot with a slope of 2 or greater. An

exception is the sharp-crested rectangular weir, which plots with a slope slightly greater than 1,5. Logarithmic

ratings for section controls in natural channels will almost always have a slope of 2 or greater. This characteristic

slope of 2 or greater for most section controls allows the analyst to identify easily the existence of section control

conditions simply by plotting discharge versus effective depth, (h-e), on logarithmic plotting paper.

Rating curves for channel controls, on the other hand, are governed by equation (2) or (3), and when plotted as

effective depth versus discharge the slope will usually be between 1,5 and 2. Variations in the slope of the rating

when channel control exists are the result of changes in rugosity and friction slope as depth changes.

The above discussion applies to control sections of regular shape (triangular, trapezoidal, parabolic, etc.). When a

significant change in shape occurs, such as a trapezoidal section control with a small V-notch for extreme low

water, there will be a change in the rating curve slope at the point where the control shape changes. Likewise, when

the control changes from section control to channel control, the logarithmic plot will show a change in slope. These

©

changes are usually defined by short curved segments of the rating, referred to as transitions. This kind of

knowledge about the plotting characteristics of a rating curve is extremely valuable in the calibration and

maintenance of the rating, and in later analysis of shifting control conditions. By knowing the kind of control (section

or channel), and the shape of the control, the analyst can more precisely define the correct hydraulic shape of the

rating curve. In addition, these kinds of information allow the analyst to extrapolate accurately a rating curve, or

conversely, know when extrapolation is likely to lead to significant errors

Figure 2 gives examples of a hypothetical rating curve showing the logarithmic plotting characteristics for channel

and section controls, and for cross-section shape changes. Insert A in figure 2 shows a trapezoidal channel with no

flood plain and with channel control conditions. The corresponding logarithmic plot of the rating curve, when plot ted

with an effective gauge height of zero flow (e) that results in a straight fine rating, has a slope less than 2. In insert B

a flood plain has been added which is also channel control. This is a change to the shape of the control cross-

section, and results in a change in the shape of the rating curve above bankful stage. If the upper segment (above

the transition curve) were replotted to the correct value of effective gauge height of zero flow, it too would have à

slope less than 2. In the third plot, insert C, a section control for low flow has been added. This results in a change

in rating curve shape because of the change in control. For the low water part of the rating, the slope will usually be

greater than 2.

Figure 3 is a logarithmic plot of an actual rating curve, using the measurements shown in table 1. This rating is for a

real stream where section control exists throughout the range of flow, including the high flow measurements. The

effective gauge height of zero flow (e) for this stream is 0,6 metres, which is subtracted from the gauge height of the

measurements to define the effective depth of flow at the control. The slope of the rating below 1,4 m is about 4,3,

which is greater than 2 and conforms to a section control. Above1,5 m, the slope is 2,8, which also conforms to a

section control. The change in slope of the rating above about 1,5 m is caused by a change in the shape of the

control cross-section. Below about 1,4 m the control section is essentially a triangular shape. In the range of 1,4 to

1,5 m the control shape is changing to trapezoidal, resulting in the transition curve of the rating. And above about

1,5 m the control cross-section is basically trapezoidal.

The examples of figures 2 and 3 are intended to illustrate some of the principals of logarithmic plotting. The analyst

should try to use these principals to the best extent possible, but should always be aware that there are probably

exceptions and differences that occur at some sites.

©

ISO

Figure 2 — Relation of channel and control properties to rating curve shape

NOTE — Numbers indicated against plotted observations refer to ID numbers given in table 1.

Figure 3 — Logarithmic plot of stage-discharge relation

6.2.4.1 Gauge height of zero flow

The actual gauge height of zero flow is the gauge height of the lowest point in the control cross-section for a section

control [sometimes referred to as the cease-to-flow (CTF) value]. For natural channels, this value can sometimes be

measured in the field by measuring the depth of flow at the deepest place in the control section, and subtracting this

depth and the velocity head from the gauge height at the time of measurement.

The effective gauge height of zero flow is a value that, when subtracted from the mean gauge heights of the

discharge measurements, will cause the logarithmic rating curve to plot as a straight fine. For regular shaped

section controls, the effective gauge height of zero flow will be nearly the same as the actual gauge height of zero

flow. For irregular shaped controls, the effective gauge height of zero flow is greater than the actual gauge height of

zero flow. At points where the control shape changes significantly, or where the control changes from section

©

control to channel control, the effective gauge height of zero flow will usually change. This results in a need to

analyze rating curves in segments (separate logarithmic plots for each control condition) to properly define the

correct hydraulic shape for each control condition. The gauge height minus the effective gauge height of zero flow is

the effective depth of flow on the control.

The effective gauge height of zero flow should be determined for each rating curve segment. For regular shaped

controls, this value will be close to the actual gauge height of zero flow. For most controls, however, a more exact

determination can be made by a trial-and-error method of plotting. A value is assumed, and measurements are

potted based on this assumed value. If the resulting curve shape is concave upward, then a somewhat larger value

for the effective gauge height of zero flow should be used. A somewhat smaller value should be used if the curve

plots concave downward. Usually only a few trials are needed to find a value that results in a straight fine for the

rating curve segment. The effective gauge height of zero flow is sometimes referred to as the logarithmic scale

offset.

6.2.4.2 Logarithmic equation

The equation for a straight line rating curve on logarithmic plotting paper is:

b

Q = p(h 2 e) (4)

where

(h 2 e) is the effective depth of water on the control,

h is the gauge height of the water surface,

e is the effective gauge height of zero flow,

b is the slope of the rating curve, and

p is a constant that is numerically equal to the discharge when the effective depth of flow (h 2 e) is

equal to 1.

6.3 Curve fitting

6.3.1 General

The curve fitting process for stage-discharge relations includes the actual drawing, positioning, and shaping of the

rating. Hydraulic analysis and mathematical fitting can be used to aid in the curve fitting process, but in the final

analysis, the stage-discharge relation must conform to the calibration measurements. On the other hand, the

analyst must realize that the rating should be hydraulically correct, and that every calibration measurement does not

necessarily fit on the same rating curve because of shifting control conditions that sometimes occur. The curve

fitting process should result in curve shapes that conform to control changes, as described in previous clauses.

6.3.2 Graphical curves

Graphical curves are those that are drawn with the aid of drawing instruments such as straight edges and pre-

shaped plastic curves. The analyst first plots the calibration measurements, determines which of these should be on

the rating curve, and then fits a curve or straightedge to the measurements by eye to produce a smooth curve with

as little variation from the measurements as possible. The analyst should always consider all available information

about the control and the actual gauge height of zero flow in order to give proper consideration to transition curves

and other changes in the shape and slope of the rating curve. Graphical fitting of rating curves is aided considerably

if plotting is performed on logarithmic plotting paper and careful choice of effective gauge height of zero flow is

made. In so doing, it is usually possible to define segments of rating curves by a straight fine rather than a curved

line.

6.3.3 Hydraulic equation curves

The shape of stage-discharge relations can sometimes be defined through the use of hydraulic equations, namely

equations (1), (2) and (3). Where section control exists, the weir equation (1) can be used to compute rating curve

points. Coefficients of discharge, C , are defined in other International Standards for certain types of weirs and

©

ISO

flumes, so that a reasonably accurate rating curve can be computed that will conform to correct hydraulics. For

natural section controls, such as a rock outcrop or sand bar, the coefficient of discharge can be estimated on the

basis of calibration measurements. Widths and depths can be determined from a surveyed cross-section of the

control section.

For segments of the rating curve that are influenced by channel control, the shape of the rating can be defined

through the use of equation (2) or (3). An average or typical cross-section in the control reach is surveyed to define

the channel characteristics of cross-section area and hydraulic radius. The Manning rugosity, n, or the Chezy C is

estimated from field observations. The friction slope is estimated from channel surveys, maps, or calibration

measurements. Equation (2) or (3) can then be used to compute discharge for a few selected gauge heights to

define the shape of the rating curve. This is a simplified procedure which assumes steady, uniform flow. More

complex situations involving non-uniform flow can be analyzed with various techniques of backwater curve

computation. Computer programs are available for such analyses.

For either case, section or channel control, the rating computed by the hydraulic equations is used only for defining

the hydraulic shape of the rating. The correct position of the rating is defined by the calibration measurements. This

procedure can also be used to aid in determining when measurements define a new rating position, such as may be

the result of a shifting control.

6.3.4 Mathematical rating curves

For gauging stations where the control is stable with little or no shifting, the stage-discharge relation can be defined

by mathematical computations, such as regression analysis. Care should be taken, however, because if the

calibration measurements used for regression are not all part of the same rating curve, then the regression results

may define a rating that is not hydraulically correct. Such a rating can lead to erroneous results when applying the

rating for the purpose of computing daily discharges.

Ratings defined by regression analysis should not be used through transition segments or through segments of the

rating that are affected by changes in control shape. Second- or third-order polynomials might be useful to define

these changes in rating shapes. The analyst should use care, however, to be sure the rating shape is hydraulically

reasonable.

6.4 Combination control stage-discharge relations

Combination control rating curves are sometimes referred to as compound control rating curves. A compound

control may consist of two section controls, each of which controls a segment of the rating curve. For instance, a

rock riffle section may control extreme low flows, but at higher flows a different cross-section located downstream

from the rock riffle may cause submergence of the rock riffle and become the controlling section for medium flows.

The plot of such a rating will usually exhibit a change in slope that reflects the change in effective gauge height of

zero flow for the two section controls. Also, there will usually be a transition curve between the two rating segments

which represents partial controlling effect from each of the controls. Graphical analysis of compound, or

combination, controls of this type requires separate logarithmic plots for each segment of the rating in order to

define the segments as straight lines, and properly compute the rating curve slope. When analyzed in this manner,

the rating curve slope for each segment will be greater than 2.

A compound rating may also be a combination of section control for low flows and channel control for medium or

high flows. This has been discussed to some extent in previous clauses. Graphical analysis usually requires that

separate plots be made for the section control segment and the channel control segment. A transition curve

between the two segments will represent the range of flow where there is partial control from both the section and

channel controls. The slope of the section control segment should be greater than 2, and the channel control

segment less than 2, when analyzed in this manner.

6.5 Stable stage-discharge relations

A stable stage-discharge relation is one that does not vary, or change positions, over a period of time. Such a

relation results from stable channel and control conditions, which for natural channels is a relative term. Virtually all

natural channels are subject to at least occasional change as a result of scour, deposition, or growth of vegetation.

©

For stable channels and controls, the stage-discharge relation can usually be defined easily by fitting a curve to the

calibration measurements as described in previous clauses. The example shown in figure 3 represents a stable

stage-discharge relation because the control is a natural section of rock outcropping that is not subject to change.

Shifts of this rating can occur, however, because of debris that might accumulate on the control.

6.6 Unstable stage-discharge relations

Unstable stage-discharge relations are defined as those that shift and change positions frequently. Channel

geometry and friction properties, and hence the control characteristics, vary continuously as a function of time, and

so also does the stage-discharge relation. These conditions are most evident during floods and during periods when

ice or vegetative growth occur. Channel scour and deposition may be a frequent occurrence in some channels due

to the nature of the bed and bank materials, thus causing shifts of the rating. Likewise, weeds, trees and other

vegetation may affect the relation between stage and discharge during certain times of the year.

It is usually not possible to define all changes of the rating with discharge measurements for unstable channels and

controls. Shifting control techniques should then be used to estimate the position of the rating during periods of time

between measurements. These techniques are described in a subsequent clause.

For some gauging stations where unstable channel conditions exist, it is sometimes advisable to install a weir or

flume, if practicable, to stabilize the rating. In other cases, if the rating is unstable because of variable backwater, a

twin-gauge system might be used. This method is described briefly in a subsequent clause, and in detail in

ISO/TR 9123. Another possible way of defining the rating where variable backwater exists is to use an index

velocity gauge in conjunction with the stage gauge. Two types of index velocity gauge can be used, the

electromagnetic type and the ultrasonic type. These are described in detail in ISO 9213 and 6416.

6.7 Shifting controls

Shifting controls occur when channel conditions are unstable, as described in previous clauses. When this condition

exists, discharge measurements made at different times represent different positions of the rating curve. Frequent

discharge measurements should be made during a period of shifting control to define the stage-discharge relation,

or magnitude of shifts, during that period. However, even with infrequent discharge measurements the stage-

discharge relation can be estimated with reasonably good accuracy if the few available discharge measurements

are supplemented with a knowledge of shifting-control behaviour.

Minor deviations of discharge measurements may result from minor random fluctuations resulting from the dynamic

force of moving water. Also, it is recognized that discharge measurements are not error-free. Consequently, an

average rating curve drawn in such a way that the discharge measurements are evenly balanced about the curve

may result in a more accurate determination of discharge than any single measurement. If a group of consecutive

discharge measurements subsequently plot to the right or left of the rating curve, it is usually clear that a shift in the

rating has occurred. On the other hand, if a single discharge measurement departs significantly from the rating, it

may not be clear whether this represents a shift or some unexplained error in the discharge measurement. The

analyst must ultimately be the judge as to whether or not a measurement or group of measurements define a

control shift. Such rating changes may be highlighted by plotting the deviation of each gauging from an average

rating curve versus time. The deviations may be expressed as either percentages, stage differences or

standardized residuals.

When discharge measurements indicate a shift of the rating curve, the analyst may determine if the shift is a

temporary condition, or if it may be permanent. If the shift is expected to last for several months or longer it may be

best to draw a new rating curve. If the shift is a temporary condition that may change again soon, then it is best to

handle the shifting control condition by drawing a temporary shift curve to define discharge during the time of shift

and until new information indicates another shift of the rating. Experience and knowledge of each control is the best

way of knowing whether rating shifts are temporary or permanent.

Shift curves are usually shaped similar to the original rating curve. That is why it is important to have the original, or

base, rating curve shaped correctly as defined by the hydraulics of the stream channel. Scour or deposition of a

natural section control results in a change in the actual and effective gauge height of zero flow. This frequently

results in a shift curve that is parallel to the original rating curve when plotted on arithmetic plotting paper. That is,

the difference in gauge height between the original rating and the shift curve is equal through a range in stage

controlled by the section control. This same shift curve, if plotted on logarithmic plotting paper, will be concave

©

ISO

upward and above the original rating for a deposition condition, and concave downward and below the original

rating for a scour condition. If a determination of the actual gauge height of zero flow was made at the time of the

discharge measurement, then this is equivalent to having a second discharge measurement which can greatly help

in defining the shift curve position and shape.

Shift curves for section controls tend to be asymptotic to the original rating at the higher stages of section control.

This is usually a good place to merge a shift curve with the base rating, because shifts that apply to a section

control probably do not apply to the channel control, or they may become so small relative to channel control

discharges that percentage-wise they are insignificant. The transition curve between section control and channel

control ratings is a good place to merge shift curves and base ratings if it is determined that a shift of one does not

apply to the other.

Channel scour, deposition and vegetative growth are usually the causes of shifts when channel control exists.

Scour usually occurs during stream rises, and deposition occurs during stream recessions. This is an over-

simplification, however, because the process of sediment transport is complex and in reality cannot be analyzed

easily. In fact, for some stream reaches, scour and deposition may be occurring simultaneously at different places

in the channel control reach. Discharge measurements are very important for defining shift curves during flood

conditions if shifting control is likely to occur.

When several discharge measurements made over a period of time appear to lie on the same shift curve, it is

usually best to draw an average shift curve to use during the period of the measurements. This average shift curve

is probably more accurate than any one of the individual measurements. The analyst should carefully determine,

however, that the average shift curve is logical and hydraulically accurate. A shift curve that departs significantly

from correct hydraulic conditions will lead to erroneous determinations of discharge during periods when discharge

measurements are not available.

For streams that shift continuously, it is usually necessary to define shift curves on the basis of discharge

measurements, determinations of the gauge height of zero flow, and hydraulic characteristics of the rating curve,

and then continuously adjust the shift curve between itself and another shift curve (or the base rating) on the basis

of time. The shift curve adjustment may be uniform, or proportional, based on time, or if specific changes can be

defined, a shift curve can be abruptly changed to correspond to the control change. For instance, a deposition of

debris on a section control may quickly wash out during a small rise, thus causing a shift curve to change back to

the original rating or to another position of the shift curve. This can sometimes be detected by examination of the

gauge height record, where abrupt changes may signify abrupt changes to the control. Where no obvious reason

can be determined for a s

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...