ISO 24617-6:2016

(Main)Language resource management — Semantic annotation framework — Part 6: Principles of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles)

Language resource management — Semantic annotation framework — Part 6: Principles of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles)

ISO 24617-6:2016 specifies the approach to semantic annotation characterizing the ISO Semantic annotation framework (SemAF). It outlines the SemAF strategy for developing separate annotation schemes for certain classes of semantic phenomena, aiming in the long term to combine these into a single, coherent scheme for semantic annotation with wide coverage. In particular, it sets out the notions of both an abstract and a concrete syntax for semantic annotations, mirroring the distinction between annotations and representations that is made in the ISO Linguistic Annotation Framework. It describes the role of these notions in relation to the specification of a metamodel and a semantic interpretation of annotations, with a view to defining a well-founded annotation scheme. ISO 24617-6:2016 also provides guidelines for dealing with two issues regarding the annotation schemes defined in SemAF-parts: a) conceptual and terminological inconsistencies that may arise due to overlaps between annotation schemes and b) the treatment of semantic phenomena that cut across SemAF-parts, such as negation, modality and quantification. Instances of both issues are identified, and in some cases, direction is given as to how they may be tackled.

Gestion des ressources linguistiques — Cadre d'annotation sémantique — Partie 6: Principes d'annotation sémantique (SemAF Principes)

Upravljanje z jezikovnimi viri - Ogrodje za semantično označevanje (SemAF) - 6. del: Načela semantičnega označevanja (načela SemAF)

Ta del standarda ISO 24617 določa pristop k semantičnemu označevanju, ki je značilno za ogrodje za semantično označevanje ISO (SemAF). Opredeljuje strategijo ogrodja semantičnega označevanja za razvijanje ločenih shem označevanja, ki so namenjene nekaterim razredom semantičnih fenomenov, pri čemer dolgoročno namerava združiti te sheme v enojno, celovito shemo za obsežno semantično označevanje. Zlasti določa pojme abstraktne in konkretne sintakse semantičnega označevanja, ki ustrezajo razliki med označevanjem in predstavitvami, podani v ogrodju za jezikoslovno označevanje ISO.

Opisuje vlogo teh pojmov v povezavi s specifikacijo metamodela in semantične razlage označevanja ter podaja pogled na opredelitev dobro utemeljene sheme označevanja.

Ta del standarda ISO 24617 podaja tudi navodila za obravnavanje dveh težav, povezanih s shemami označevanja, opredeljenimi v delih ogrodja za semantično označevanje: a) pojmovne in terminološke nedoslednosti, do katerih lahko pride zaradi prekrivanja shem označevanja, ter b) obravnavanje semantičnih fenomenov, kot so negacija, modalnost in kvantifikacija, ki so v nasprotju z deli ogrodja za semantično označevanje. Obravnavani sta obe težavi in v nekaterih primerih so podana navodila, kako ju je mogoče odpraviti.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 31-Jan-2016

- Technical Committee

- ISO/TC 37/SC 4 - Language resource management

- Drafting Committee

- ISO/TC 37/SC 4/WG 2 - Semantic annotation

- Current Stage

- 9093 - International Standard confirmed

- Start Date

- 29-Oct-2021

- Completion Date

- 14-Feb-2026

Overview

ISO 24617-6:2016 - Language resource management - Semantic annotation framework - Part 6: Principles of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles) - defines the methodological and conceptual basis of the ISO Semantic Annotation Framework (SemAF). It documents the strategy for developing separate, interoperable annotation schemes for discrete semantic phenomena (e.g., time/events, dialogue acts, semantic roles) with the long‑term goal of integrating these into a single, coherent wide‑coverage semantic annotation scheme.

Key themes in the standard include the distinction between abstract syntax and concrete syntax for annotations, the specification of a metamodel, and the requirement for a clear semantic interpretation of annotation objects. The standard also addresses consistency across SemAF parts and gives guidance on cross‑cutting semantic phenomena such as negation, modality, and quantification.

Key topics and technical requirements

- Purpose and motivation: promote methodological coherence across SemAF parts and reduce risks arising from separately developed schemes.

- Metamodel: define schematic concepts and relationships used in annotation schemes (conceptual backbone for interoperability).

- Abstract vs. concrete syntax: separate the annotation’s conceptual structure (abstract) from its representational format (concrete), mirroring the ISO Linguistic Annotation Framework (ISO 24612).

- Semantic interpretation: require well‑founded semantics for annotations to ensure consistent meaning across resources.

- Design methodology: staged steps for creating annotation schemes, including feedback loops and optional elements to increase reuse.

- Handling overlaps: procedures to identify and mitigate terminological or conceptual inconsistencies between parts (e.g., spatial/temporal relations appearing as semantic roles).

- Cross‑cutting phenomena: guidance for annotating modalities, polarity/negation, quantification, measures and attribution when these cut across different SemAF parts.

Practical applications and target users

Who benefits:

- NLP and computational semantics researchers building annotated corpora.

- Corpus linguists and language resource developers creating interoperable semantic annotations.

- Annotation-tool and platform developers implementing standards‑compatible formats (abstract/concrete syntax separation helps tool interoperability).

- Machine‑learning engineers training models for event extraction, temporal reasoning, question answering, dialogue systems and semantic parsing.

- Standards bodies and project managers coordinating multi‑part annotation schemes.

Practical advantages:

- Improved interoperability of semantic resources across projects and tools.

- Clearer foundations for combining annotations (e.g., time, spatial info, semantic roles) to support higher‑level applications such as text‑based question answering or automated semantic extraction.

- Reduced ambiguity when multiple SemAF parts interact, making datasets more robust for ML training and evaluation.

Related standards

- ISO 24617 series (SemAF): Part 1 (Time and events, ISO‑TimeML), Part 2 (Dialogue acts), Part 4 (Semantic roles), Part 5 (Discourse structures), Part 7 (Spatial information); Parts 8 and 9 under preparation.

- ISO 24612: Linguistic Annotation Framework - referenced for the annotations vs representations distinction.

For authoritative details and purchasing the full text, consult ISO (www.iso.org) or your national standards body.

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO 24617-6:2016 is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Language resource management — Semantic annotation framework — Part 6: Principles of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles)". This standard covers: ISO 24617-6:2016 specifies the approach to semantic annotation characterizing the ISO Semantic annotation framework (SemAF). It outlines the SemAF strategy for developing separate annotation schemes for certain classes of semantic phenomena, aiming in the long term to combine these into a single, coherent scheme for semantic annotation with wide coverage. In particular, it sets out the notions of both an abstract and a concrete syntax for semantic annotations, mirroring the distinction between annotations and representations that is made in the ISO Linguistic Annotation Framework. It describes the role of these notions in relation to the specification of a metamodel and a semantic interpretation of annotations, with a view to defining a well-founded annotation scheme. ISO 24617-6:2016 also provides guidelines for dealing with two issues regarding the annotation schemes defined in SemAF-parts: a) conceptual and terminological inconsistencies that may arise due to overlaps between annotation schemes and b) the treatment of semantic phenomena that cut across SemAF-parts, such as negation, modality and quantification. Instances of both issues are identified, and in some cases, direction is given as to how they may be tackled.

ISO 24617-6:2016 specifies the approach to semantic annotation characterizing the ISO Semantic annotation framework (SemAF). It outlines the SemAF strategy for developing separate annotation schemes for certain classes of semantic phenomena, aiming in the long term to combine these into a single, coherent scheme for semantic annotation with wide coverage. In particular, it sets out the notions of both an abstract and a concrete syntax for semantic annotations, mirroring the distinction between annotations and representations that is made in the ISO Linguistic Annotation Framework. It describes the role of these notions in relation to the specification of a metamodel and a semantic interpretation of annotations, with a view to defining a well-founded annotation scheme. ISO 24617-6:2016 also provides guidelines for dealing with two issues regarding the annotation schemes defined in SemAF-parts: a) conceptual and terminological inconsistencies that may arise due to overlaps between annotation schemes and b) the treatment of semantic phenomena that cut across SemAF-parts, such as negation, modality and quantification. Instances of both issues are identified, and in some cases, direction is given as to how they may be tackled.

ISO 24617-6:2016 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 01.020 - Terminology (principles and coordination). The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO 24617-6:2016 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-oktober-2018

Upravljanje z jezikovnimi viri - Ogrodje za semantično označevanje (SemAF) - 6.

del: Načela semantičnega označevanja (načela SemAF)

Language resource management -- Semantic annotation framework -- Part 6: Principles

of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles)

Gestion des ressources linguistiques -- Cadre d'annotation sémantique -- Partie 6:

Principes d'annotation sémantique (SemAF Principes)

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: ISO 24617-6:2016

ICS:

01.020 Terminologija (načela in Terminology (principles and

koordinacija) coordination)

01.140.20 Informacijske vede Information sciences

35.240.30 Uporabniške rešitve IT v IT applications in information,

informatiki, dokumentiranju in documentation and

založništvu publishing

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 24617-6

First edition

2016-02-01

Language resource management —

Semantic annotation framework —

Part 6:

Principles of semantic annotation

(SemAF Principles)

Gestion des ressources linguistiques — Cadre d’annotation

sémantique —

Partie 6: Principes d’annotation sémantique (SemAF Principes)

Reference number

©

ISO 2016

© ISO 2016, Published in Switzerland

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior

written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of

the requester.

ISO copyright office

Ch. de Blandonnet 8 • CP 401

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva, Switzerland

Tel. +41 22 749 01 11

Fax +41 22 749 09 47

copyright@iso.org

www.iso.org

ii © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

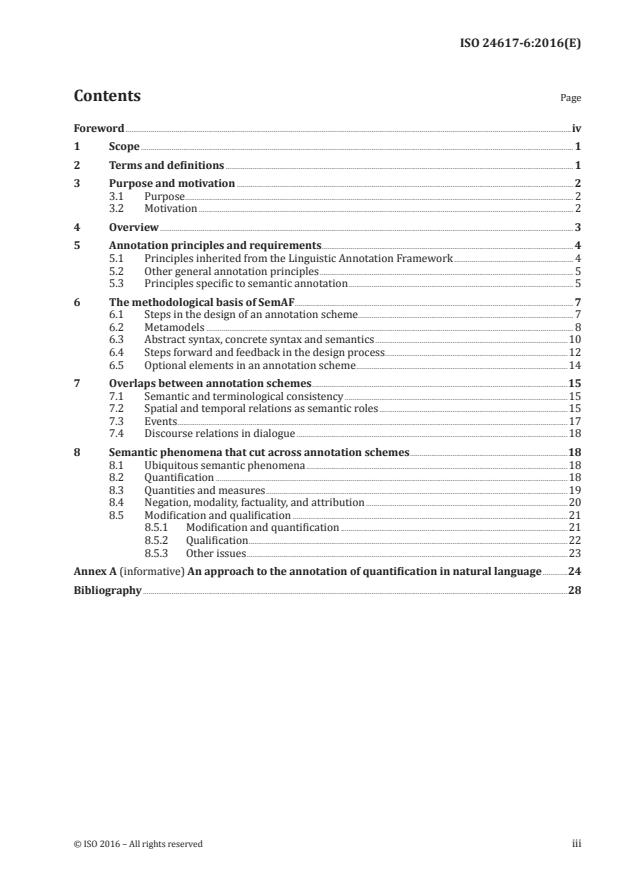

Contents Page

Foreword .iv

1 Scope . 1

2 Terms and definitions . 1

3 Purpose and motivation . 2

3.1 Purpose . 2

3.2 Motivation . 2

4 Overview . 3

5 Annotation principles and requirements . 4

5.1 Principles inherited from the Linguistic Annotation Framework . 4

5.2 Other general annotation principles . 5

5.3 Principles specific to semantic annotation . 5

6 The methodological basis of SemAF . 7

6.1 Steps in the design of an annotation scheme . 7

6.2 Metamodels . 8

6.3 Abstract syntax, concrete syntax and semantics .10

6.4 Steps forward and feedback in the design process .12

6.5 Optional elements in an annotation scheme .14

7 Overlaps between annotation schemes .15

7.1 Semantic and terminological consistency .15

7.2 Spatial and temporal relations as semantic roles .15

7.3 Events .17

7.4 Discourse relations in dialogue .18

8 Semantic phenomena that cut across annotation schemes .18

8.1 Ubiquitous semantic phenomena .18

8.2 Quantification .18

8.3 Quantities and measures .19

8.4 Negation, modality, factuality, and attribution .20

8.5 Modification and qualification .21

8.5.1 Modification and quantification .21

8.5.2 Qualification .22

8.5.3 Other issues .23

Annex A (informative) An approach to the annotation of quantification in natural language .24

Bibliography .28

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation on the meaning of ISO specific terms and expressions related to conformity

assessment, as well as information about ISO’s adherence to the WTO principles in the Technical

Barriers to Trade (TBT) see the following URL: Foreword - Supplementary information.

The committee responsible for this document is ISO/TC 37, Terminology and other language and content

resources, Subcommittee SC 4, Language resource management.

ISO 24617 consists of the following parts, under the general title Language resource management —

Semantic annotation framework (SemAF):

— Part 1: Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISOTimeML)

— Part 2: Dialogue acts (SemAF-Dacts)

— Part 4: Semantic roles (SemAF-SR)

— Part 5: Discourse structures (SemAF-DS) [Technical Specification]

— Part 6: Principles of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles)

— Part 7: Spatial information (ISOspace)

The following parts are in preparation:

— Part 8: Semantic relations in discourse (SemAF DR-core)

— Part 9: Reference (ISOref)

iv © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 24617-6:2016(E)

Language resource management — Semantic annotation

framework —

Part 6:

Principles of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles)

1 Scope

This part of ISO 24617 specifies the approach to semantic annotation characterizing the ISO Semantic

annotation framework (SemAF). It outlines the SemAF strategy for developing separate annotation

schemes for certain classes of semantic phenomena, aiming in the long term to combine these into a

single, coherent scheme for semantic annotation with wide coverage. In particular, it sets out the

notions of both an abstract and a concrete syntax for semantic annotations, mirroring the distinction

between annotations and representations that is made in the ISO Linguistic Annotation Framework.

It describes the role of these notions in relation to the specification of a metamodel and a semantic

interpretation of annotations, with a view to defining a well-founded annotation scheme.

This part of ISO 24617 also provides guidelines for dealing with two issues regarding the annotation

schemes defined in SemAF-parts: a) conceptual and terminological inconsistencies that may arise due

to overlaps between annotation schemes and b) the treatment of semantic phenomena that cut across

SemAF-parts, such as negation, modality and quantification. Instances of both issues are identified, and

in some cases, direction is given as to how they may be tackled.

2 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

NOTE In addition, the terms ‘event’ and ‘eventuality’ are used (as synonyms) as defined in ISO 24617-1 as

something that can be said to obtain or hold true, to happen or to occur.

2.1

primary data

electronic representation of text or communicative behaviour

EXAMPLE Digital representations of text, transcriptions of speech, gestures or multimodal dialogue.

Note 1 to entry: ISO 24612 defines primary data as the ‘electronic representation of language data’. This definition

is unsatisfactory for this part of ISO 24617 as semantic annotation may relate to non-verbal or multimodal data,

such as stretches of spoken dialogue with accompanying gestures and facial expressions, and even gestures

and/or facial expressions without any accompanying speech.

2.2

annotation

linguistic information added to primary data (2.1), independent of its representation

[SOURCE: ISO 24612:2012, 2.3]

2.3

semantic annotation

annotation (2.2) which contains information about the meaning of a segment or region of primary data

(2.1)

2.4

metamodel

schematic representation of the concepts that are used in the analysis and description of the phenomena

covered in annotations (2.2) and of the relationships between them

3 Purpose and motivation

3.1 Purpose

The purpose of this part of ISO 24617 is to provide support for the establishment of a consistent and

coherent set of international standards for semantic annotation within the Semantic Annotation

Framework (SemAF). It aims to do so in three ways.

First, by making explicit which basic principles underlie the approach that has been followed in

defining international standards in the SemAF parts that have been published so far (ISO 24617-1 and

ISO 24617-2, ISO 24617-4 and ISO 24617-7), and in parts that are close to publication (ISO 24617-6)

or in preparation (ISO 24617-8). This approach provides the Semantic Annotation Framework with

methodological coherence and helps to ensure mutual consistency between existing, developing, and

future SemAF parts.

Second, by identifying overlaps between SemAF parts and indicating how such overlaps may be dealt

with. Examples are the occurrence of temporal and spatial relations among semantic roles and of

discourse relations between dialogue acts.

Third, by identifying common issues that arise in various parts of SemAF (they are only partly covered

in these parts, if they are covered at all) and, where possible, by giving directions as to how these issues

may be tackled. Examples of such issues are polarity, modality, quantification, measures, qualification,

veridicity, attribution and non-literal language use.

3.2 Motivation

Semantic annotation enhances primary data with information about their meaning. The state of the art

in computational semantics makes it unlikely that a single existing formalism for annotating semantic

information would receive wide support from researchers and developers. Moreover, semantic

annotation tasks often have the limited aim of annotating certain specific semantic phenomena,

such as semantic roles, discourse relations or coreference relations, rather than annotating the full

meaning of stretches of primary data. A strategy was therefore adopted in ISO TC 37/SC 4 to devise the

SemAF standards in different parts, with separate annotation schemes for those classes of semantic

phenomenon for which the state of the art would justify the establishment of annotation standards;

these schemes could be extended and combined over time, growing into a wide-coverage framework for

semantic annotation.

This ‘crystal growth’ strategy has contributed significantly to the progress made in establishing

standardized annotation concepts and schemes supporting the development of interoperable resources,

but it also entails certain risks:

a) the annotation schemes defined in different SemAF parts are not necessarily mutually consistent,

especially in the case of overlaps in scope;

b) it may not be possible to combine the schemes, defined in different parts, into a coherent single

scheme with a wider coverage if they incorporate different views or employ different methodologies;

c) some semantic phenomena do not belong to the scope of any SemAF parts but cannot be disregarded

entirely in some parts, and this may result in these phenomena being unsatisfactorily treated.

The methodological principles and guidelines provided in this part of ISO 24617 are designed to

minimize these risks.

2 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

With regard to the issue of mutual consistency between SemAF parts, it may be noted that ISO 24617-1

for annotating time and events and ISO 24617-2 for annotating dialogue acts are concerned with

sufficiently distinct kinds of semantic information to allow their definitions to be established

independently. Other SemAF parts, such as those concerned with semantic roles, with relations in

discourse and with spatial information show a certain amount of overlap in the information that they

aim to capture, and the question therefore arises: can we ensure that the annotation schemes, defined

in these parts, are mutually consistent?

Mutual consistency of SemAF parts relates to the possible integration of annotation schemes defined

in different parts. For example, it would be desirable to use the ISO 24617-1 scheme (“ISO-TimeML”) for

annotating time and events in combination with the ISO 24617-4 scheme for semantic roles, thereby

annotating coherently not only the events identified in the data with their temporal properties, but

also the way in which these events are related to their participants. Integrating these annotations with

those of spatial information, using the ISO 24617-7 scheme for spatial information, would be another

plausible and desirable step, given that time and space are intertwined with concepts relating to motion

and velocity. More generally, the integration of SemAF parts would greatly enhance the significance

of the individual parts; in the end, SemAF’s ‘crystal growth’ strategy of SemAF is only really useful

if the annotation schemes defined in the various parts can grow into a single scheme with a wide

coverage of semantic phenomena. Only then can it effectively support such applications as text-based

question answering or extracting semantic information from text, and form the basis for automatically

recognizing semantic phenomena by means of machine-learning techniques. Clearly, this is only possible

if the annotation schemes are mutually consistent (e.g. they use the same classification of event types),

and are coherent whether, for example, temporal and spatial objects are viewed as event participants

or as the circumstances of an event.

With regard to the risk of unsatisfactory partial treatments of phenomena that are not among the

core issues of any (current) SemAF part, it should be noted that some of these phenomena cut across

several of these parts and are important for semantics-driven applications. Negation, or more generally

negative polarity, and quantification are two cases in point. Given that the aim in ISO-TimeML, for

instance, is to support the annotation of events, of their relation to time, and of the temporal relations

among temporal objects, it is desirable to be able to deal with sentences like the following:

(1) John teaches every Monday.

(2) Mary called twice this morning.

(3) John rang home twice a day.

Sentence (1) is about a set of “teach” events, each of which is related to a different element of the set of

temporal objects that are called “Monday”, so this is a case of quantification involving two sets, a set of

events and sets of days. Similarly, sentence (2) about a set of two “call” events, both related to the same

period of time. Sentence (3) is about a set of events and their frequency of occurrence.

In order to deal with such phenomena, ISO-TimeML has certain provisions for annotating quantification,

[13]

but they are not really adequate and do not generalize to cases of quantification where no events

are involved.

4 Overview

The ISO efforts aiming to develop standards for semantic annotation rest on certain basic principles,

some of which have been laid out by Reference [14] as requirements for semantic annotation, and

have been developed further in Reference [5]; others have been formulated as general principles for

linguistic annotation and are part of the ISO Linguistic Annotation Framework (LAF; see Reference [18]

and ISO 24623-1). The two sets of principles and requirements are considered in Clause 5.

The three kinds of risk associated with the SemAF ‘crystal growth’ strategy that have been identified

above correspond to the following issues of consistency and completeness that arise in the design of

semantic annotation schemes within the SemAF framework.

Consistency among annotation schemes:

— methodological consistency: the same basic approach is followed with respect to the distinction

between abstract and concrete syntax and their interrelation, and with respect to their semantics;

— conceptual consistency: different schemes are based on compatible underlying views and ontological

assumptions regarding their basic concepts, as reflected in metamodels (e.g. verbs are viewed as

denoting states or events, rather than relations);

— terminological consistency: terms that occur in different annotation schemes have the same meaning

in every scheme and the same term is used across annotation schemes to indicate the same concept.

Completeness of a set of annotation schemes: the combination of multiple annotation schemes leads to

a scheme that

— covers a wide range of semantic phenomena,

— does not have significant gaps when covering the semantic phenomena that it aims to cover, and

— deals in a satisfactory way with semantic phenomena that cut across the combined schemes but

which do not belong to the core phenomena that any of the combined schemes are designed to cover.

Clause 5 describes the methodological framework for defining annotation schemes in SemAF parts,

thereby ensuring methodological consistency. Clause 6 discusses conceptual and terminological

consistency issues that arise due to overlaps between SemAF parts, while Clause 7 identifies issues of

completeness regarding the annotation of semantic phenomena that cut across existing SemAF parts.

5 Annotation principles and requirements

5.1 Principles inherited from the Linguistic Annotation Framework

The annotation of semantic information when using SemAF inherits the principles for linguistic

annotation as formulated in LAF. These principles are often of a very general nature; they include the

principle that relevant segments of primary data are referred to in a uniform and TEI-compliant way,

and the principle that different layers of annotation over the primary data can co-exist by using stand-

off annotation and a uniform way of cross-referencing between layers.

The latter principle, which concerns the distinction of layers of annotation enabled by a stand-off

representation format, is of particular relevance for SemAF because it allows different annotation

layers to be used for different types of semantic information; for example, one layer could be used for

the annotation of events, time and space, and another one could be used to annotate semantic roles.

In principle, this allows for the use not only of layers that are not mutually consistent, but also of

alternative annotations that employ different annotation schemes for the same phenomena. However,

the SemAF ‘crystal growth’ strategy is designed to ensure that the annotation schemes for the various

types of semantic information can grow into a coherent annotation scheme for a wide range of semantic

phenomena, and it is therefore highly undesirable to have inconsistencies between annotation layers

concerned with different SemAF parts.

[18]

Also of particular relevance for SemAF is the distinction between ‘annotations’ and ‘representations’.

An annotation is any item of linguistic information that is added to primary data, independently of any

particular representation format. A representation is a format into which an annotation is rendered,

for example as an XML expression. ISO standards are assumed to be defined at the level of annotations,

rather than representations. The fundamental distinction between annotations and representations has

prompted the development of a methodology for developing semantic annotation schemes that draws

a distinction between the ‘abstract syntax’ of annotations and the ‘concrete syntax’ of representations.

This methodology is described in Clause 6.

4 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

5.2 Other general annotation principles

In addition to the principles that SemAF inherits from LAF, other general principles for designing

annotation schemes (in particular as part of an ISO standard) are worth mentioning; most of these

emerged during the development of the ISO 24617-2 standard for dialogue act annotation.

a) Theoretical validity: Annotation standards should consolidate existing knowledge and

accordingly should be firmly rooted in theoretical studies of the annotated phenomena. Any concept

that may occur in annotations according to the standard should therefore be well established in the

scientific literature.

b) Empirical validity: Annotation standards are designed to be useful for annotating corpora of

recorded empirical data; the annotation scheme defined in a standard should not therefore include

theoretical constructs that are not found in such corpora, but only concepts that correspond to

phenomena that are observed in empirical data.

c) Learnability: For an annotation scheme to be useful in the construction of annotated language

resources, it should be possible both for human annotators and for automatic annotation systems

to effectively learn how to apply the scheme with acceptable precision.

d) Generalizability: ISO standards should not be restricted in their applicability to particular

languages, subject domains or applications.

e) Extensibility: While ISO standard annotation schemes are designed to be language-independent,

domain-independent and application-independent, some applications and some languages may

require specific concepts that are not relevant in other applications or languages. Annotation

schemes should therefore be open, that is to say, they should allow extension with language-

specific, domain-specific and application-specific concepts.

f) Completeness: An annotation standard is designed to provide a good coverage of the phenomena of

which it is designed to enable the annotation; the set of concepts defined in an annotation standard

should, in that sense, be complete.

g) Variable granularity: One way to achieve good coverage is to include annotation concepts of a

high level of generality and which cover many specific instances. Since an annotation scheme

which uses only very general concepts would not be optimally useful, this leads to the principle

that annotation schemes should include concepts with different levels of granularity. This is also

beneficial for its interoperability, as it provides more possibilities for conversion between existing

annotation schemes and the standard scheme.

h) Compatibility: In order to enable mappings between alternative annotation schemes and thereby

contribute to the interoperability of annotated resources, concepts that are commonly found in

existing annotation schemes should preferably be included in an annotation standard.

5.3 Principles specific to semantic annotation

The idea behind annotating a text, which dates from long before the digital era, is to add information to a

primary text in order to support its understanding. The semantic annotation of digital source texts has

a similar purpose, namely to support the understanding of the text by humans, as well as by machines.

An annotation that does not add any information would therefore seem to make little sense, but the

[39]

following example of the annotation of a temporal expression using TimeML seems to do just that:

NOTE 1 For simplicity, the annotations of the events that are mentioned in the previous sentence is

suppressed here.

(4)

The CEO announced that he would resign as of

the first of December 2008

In this annotation, the subexpression

adds to the noun phrase “the first of December 2008” the information that this phrase describes: the

date 2008-12-01.This does not add any information; rather, it paraphrases the noun phrase in TimeML.

This could be useful if the expression in the annotation language had a well-specified semantics that

could be used directly by computer programs for applications like information extraction and question

answering. Unfortunately, TimeML does not have a semantics.

NOTE 2 It would be very simple to provide a semantics for the XML fragment shown here but it would be very

difficult to do so for the whole of TimeML. See also 7.3.

A case where the annotation of a date as in the above example does add something is (5). From the

utterance “Mr Brewster called a staff meeting today”, it is impossible to know the date on which the event

that is mentioned took place; in this case, the annotation, which is identical to (4), would be informative.

NOTE 3 Note that the examples of TimeML annotations shown here are “old-fashioned” in the sense that the

TIMEX3 element is wrapped around the annotated string. Modern annotation methods (e.g. in ISO-TimeML) use

stand-off representations.

(5) Mr Brewster called a staff meeting today.

Mr Brewster called a staff meeting

today

The examples in (4) and (5) illustrate two different functions that semantic annotations may have:

interpreting a natural language expression by recoding it in a formal annotation language with a well-

defined semantics, and adding context information, in order to allow the interpretation of context-

dependent expressions.

A third function that semantic annotations may have is to make explicit how certain parts of an

utterance are semantically related; for example, this is the function of semantic role labelling and of

indicating semantic relations between sentences in a discourse when no such relation is mentioned.

Note that the first function presupposes annotations to have a well-defined semantics; the other two

functions do not presuppose this, but since semantic annotations in digital corpora are typically

designed to support interpretation and inference, a desideratum for all functions that a semantic

annotation may have is that it has a well-defined semantics. Semantic annotations, like other linguistic

annotations, may also serve the purpose of supporting linguistic research, such as identifying syntactic

and semantic patterns in sentences and texts.

These considerations lead to the following two principles for semantic annotation:

— Semantic additivity: semantic annotations add semantic information to source data, or re-express

certain source data in a formal representation.

— Semantic adequacy: semantic annotations should have a well-defined semantics, making the

annotations machine-interpretable.

6 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

6 The methodological basis of SemAF

6.1 Steps in the design of an annotation scheme

An annotation scheme determines which information may be added to primary data and how that

information is expressed. The design of an annotation scheme from scratch should begin with a

conceptual analysis of the information that the annotations should capture. This analysis identifies

the concepts that form the building blocks of annotations and specifies how these blocks may be

used to build annotation structures. This may be broken down into two steps, the first establishing a

conceptual view of the phenomena to be annotated, the second an articulation of this view in the form

of a formal specification of categories of entities and relations, and of how annotation structures can be

built up from elements in these categories. The first of these steps corresponds to what is known in ISO

projects as the establishment of a ‘metamodel’, that is to say, the expression of a conceptual view of the

phenomena to be annotated in the form of a (UML) diagram. The formal specification produced in the

second step constitutes the abstract syntax of an annotation language.

While these two steps make explicit what information can be captured in the annotations, they do not

concern the use of representation formats, such as XML strings, logical formulas, graphs or feature

structures; the abstract syntax defines the specification of information in terms of set-theoretic

structures, called annotation structures. An annotation structure is a collection of two kinds of structure,

entity structures and link structures. An entity structure contains semantic information about a segment

of primary data and is formally a pair consisting of a markable, which refers to a segment of

primary data, and of certain semantic information. A link structure contains information about the way

two segments of primary data are semantically related; for example, in semantic role annotation a link

structure is a triple where e is an entity structure that contains information about an event,

1 2 i 1

e is an entity structure that contains information about a participant in the event, and R is a relation

2 i

denoting a semantic role.

The third step in the definition of an annotation scheme is the specification of the meaning of the structures

defined by the abstract syntax, that is to say, the specification of semantics for annotation structures.

The fourth and final step is the definition of a format for representing annotation structures, such as a

serialization in XML. The semantics of an expression in this format is that of the annotation structure

that it represents. In sum, this approach to designing annotation schemes consists of four steps, with as

many feedback loops as may be needed.

The method consisting of these four steps is called ‘CASCADES’: Conceptual analysis, Abstract syntax,

Semantics, and Concrete syntax for Annotation language DESign. Figure 1 visualizes the CASCADES

method, of which the central concept, that of an abstract syntax for annotations with the specification

of a semantics for annotation structures (rather than for their representations in a particular format),

was introduced in Reference [5].

The CASCADES method is useful for enabling a systematic design process, in which due attention is

given to the conceptual and semantic choices on which more superficial decisions, such as the choice

of particular XML attributes and values, should be based. Apart from supporting the design of an

annotation scheme starting from scratch, the method also provides support for improving an existing

annotation scheme. This support consists not only of the distinction of four well-defined design steps,

but also of procedures and guidelines for taking these steps. These procedures are outlined in 6.3.

But before that, the use of metamodels, resulting from the conceptual analysis phase of designing an

annotation scheme, is discussed in 6.2.

Figure 1 — Steps and feedback loops in the CASCADES method

6.2 Metamodels

A metamodel of an annotation standard is a schematic representation of the relations between

the concepts that are important in the analysis and description of the phenomena covered in the

annotations. Over the years, two slightly different notions of a metamodel have been used in ISO

projects, namely the following:

— A: as a representation of the relations between the most important concepts that are mentioned in

the document in which the standard is defined;

— B: as a representation of the relations between the concepts denoted by terms that occur in

annotations, according to the standard.

Type-A metamodels may help nontechnical readers to have a better understanding of annotation

schemes; those of type-B are a visual representation of the abstract syntax of the annotations according

to the scheme and may help readers see at a glance what information the annotations may contain.

(Note that a type-A metamodel may have a type-B metamodel as a proper part.) For example, Figure 2

shows the metamodel of ISO 24617-4 for semantic role labelling. This metamodel reflects the view that

semantic roles are relations between eventualities and their participants; different roles correspond

to different ways in which a participant is involved in an eventuality. For example, in “Chris wrote a

poem”, a poem participates in an event in the Result role (i.e. created by the event); in “Chris revised the

poem”, the poem is involved in the Patient role (i.e. affected by the event); and in “Chris read a poem”, a

poem participates in the Theme role (i.e. not affected by the event). The annotation of semantic roles

therefore involves the use both of eventualities, most often corresponding to verbs, and of participants,

typically expressed by noun phrases. The metamodel associates eventualities and participants with

markables, whose source is a stretch of text in the primary data. The participants in an eventuality are

typically individuals, but may also be properties, numbers, quantities, propositions, sets of individuals

or embedded eventualities, as the examples in (6) illustrate.

(6) a. He painted his house blue.

b. The birth of the twins increased the number of children to four.

c. The weight of this suitcase exceeds 20 kilos.

8 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

d. John believes he will get the money together.

e. Marie, Jill and Chris got together.

f. Eric and Nicole went to the concert.

Figure 2 — Metamodel for semantic role annotation (ISO 24617-4)

The term ‘entity’ is used in ISO 24617-4 to denote anything except an eventuality; the fact that a

participant in an eventuality can be an ‘entity’ of any sort as well as an (embedded) eventuality, as in (6f),

is reflected in the metamodel by the “entityFunctionsAs” relation between entities and participants,

and the “eventualityMayFunctionAs” relation between eventualities and participants. Many approaches

to semantic role labelling (e.g. PropBank, FrameNet and VerbNet) make use of “eventuality frames” that

specify the set of semantic roles expected in a type of eventuality, and take the eventuality frame as a

whole into consideration when determining the choice of individual semantic roles. For that reason,

eventuality frames have also been included in the metamodel.

Is this a type-A metamodel or a type-B metamodel? The following is an example of an annotation

representation according to ISO 24617-4 (where m1 is a markable that refers to “The soprano”; m2 is a

markable that refers to “sang”, and m3 is a markable that refers to “an aria”):

(7) a. The soprano sang an aria.

b.

In this annotation, eventualities are directly related to entities by means of an element like

event=”#e1” participant=”#x1” semRole=”agent”/>. There is no ‘participant’ object,

related to an entity via an ‘entityFunctionsAs relation’, as there is in the metamodel. It follows that

this metamodel is not just a visual representation of the (abstract) syntax of annotation structures, but

rather a type-A model, since it has elements that do not appear in annotations. This is corroborated by

the fact that eventuality frames do not occur as such in annotations; eventuality frames may be used in

the process of semantic role labelling, but are not part of the resulting annotations.

6.3 Abstract syntax, concrete syntax and semantics

The abstract syntax of an annotation scheme, as mentioned above, specifies the information in

annotations in terms of set-theoretical structures such as pairs and triples, like the triple

1 2 i

which relates the two arguments e and e through the relation R . More generally, these structures

1 2 i

are n-tuples of elements that are either basic concepts taken from a store of basic concepts called the

‘conceptual inventory’ of the abstract syntax specification, or n-tuples of such structures.

A concrete syntax specifies a representation format for annotation structures, such as the XML format

illustrated in (7), where a triple like is represented by a sequence of three XML elements,

1 2 i

of which the element

represents the relation and the other two elements represent two entity structures.

A representation format for annotation structures should ideally give an exact expression of the

information contained in annotation structures. A concrete syntax, defining a representation format

for a given abstract syntax, is said to be ideal if it has the following properties:

— completeness: every annotation structure defined by the abstract syntax can be represented by an

expression defined by the concrete syntax;

— unambiguity: every representation defined by the concrete syntax is the rendering of exactly one

annotation structure defined by the abstract syntax.

The representation format defined by an ideal concrete syntax is called an ideal representation format.

Due to its completeness, an ideal concrete syntax CS defines a function F from annotation structures

i i

−1

to CS -representations, and due to its ‘unambiguity’, there is also an inverse function F from CS -

i i i

representations to annotation structures. If I is the interpretation function defining the semantics

a

of the abstract syntax, then the meaning of a representation r in the ideal format CS is defined by

k

−1

I (F (r)). It follows that, for any two ideal representation formats CS and CS , there is a meaning-

a k i j

preserving conversion C defined by:

ij

−1

(8) C (r) = F [F (r)]

ij j i

This mapping is meaning-preserving due to the fact that the meaning of a representation is the meaning

of the annotation structure that it encodes. Since this holds for any ideal concrete syntax, it follows that

any two ideal representation formats are semantically equivalent.

Figure 3 visualizes the relations between abstract syntax, semantics, and alternative ideal concrete-

syntax specifications. It is immediately clear that a given representation r defined by concrete syntax

CS can be converted into a semantically equivalent representation r’ in the representation format CS

i j

−1

by first applying the function F in order to determine the annotation structure which it encodes, and

i

applying to that

...

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 24617-6

First edition

2016-02-01

Language resource management —

Semantic annotation framework —

Part 6:

Principles of semantic annotation

(SemAF Principles)

Gestion des ressources linguistiques — Cadre d’annotation

sémantique —

Partie 6: Principes d’annotation sémantique (SemAF Principes)

Reference number

©

ISO 2016

© ISO 2016, Published in Switzerland

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior

written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of

the requester.

ISO copyright office

Ch. de Blandonnet 8 • CP 401

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva, Switzerland

Tel. +41 22 749 01 11

Fax +41 22 749 09 47

copyright@iso.org

www.iso.org

ii © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

Contents Page

Foreword .iv

1 Scope . 1

2 Terms and definitions . 1

3 Purpose and motivation . 2

3.1 Purpose . 2

3.2 Motivation . 2

4 Overview . 3

5 Annotation principles and requirements . 4

5.1 Principles inherited from the Linguistic Annotation Framework . 4

5.2 Other general annotation principles . 5

5.3 Principles specific to semantic annotation . 5

6 The methodological basis of SemAF . 7

6.1 Steps in the design of an annotation scheme . 7

6.2 Metamodels . 8

6.3 Abstract syntax, concrete syntax and semantics .10

6.4 Steps forward and feedback in the design process .12

6.5 Optional elements in an annotation scheme .14

7 Overlaps between annotation schemes .15

7.1 Semantic and terminological consistency .15

7.2 Spatial and temporal relations as semantic roles .15

7.3 Events .17

7.4 Discourse relations in dialogue .18

8 Semantic phenomena that cut across annotation schemes .18

8.1 Ubiquitous semantic phenomena .18

8.2 Quantification .18

8.3 Quantities and measures .19

8.4 Negation, modality, factuality, and attribution .20

8.5 Modification and qualification .21

8.5.1 Modification and quantification .21

8.5.2 Qualification .22

8.5.3 Other issues .23

Annex A (informative) An approach to the annotation of quantification in natural language .24

Bibliography .28

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation on the meaning of ISO specific terms and expressions related to conformity

assessment, as well as information about ISO’s adherence to the WTO principles in the Technical

Barriers to Trade (TBT) see the following URL: Foreword - Supplementary information.

The committee responsible for this document is ISO/TC 37, Terminology and other language and content

resources, Subcommittee SC 4, Language resource management.

ISO 24617 consists of the following parts, under the general title Language resource management —

Semantic annotation framework (SemAF):

— Part 1: Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISOTimeML)

— Part 2: Dialogue acts (SemAF-Dacts)

— Part 4: Semantic roles (SemAF-SR)

— Part 5: Discourse structures (SemAF-DS) [Technical Specification]

— Part 6: Principles of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles)

— Part 7: Spatial information (ISOspace)

The following parts are in preparation:

— Part 8: Semantic relations in discourse (SemAF DR-core)

— Part 9: Reference (ISOref)

iv © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 24617-6:2016(E)

Language resource management — Semantic annotation

framework —

Part 6:

Principles of semantic annotation (SemAF Principles)

1 Scope

This part of ISO 24617 specifies the approach to semantic annotation characterizing the ISO Semantic

annotation framework (SemAF). It outlines the SemAF strategy for developing separate annotation

schemes for certain classes of semantic phenomena, aiming in the long term to combine these into a

single, coherent scheme for semantic annotation with wide coverage. In particular, it sets out the

notions of both an abstract and a concrete syntax for semantic annotations, mirroring the distinction

between annotations and representations that is made in the ISO Linguistic Annotation Framework.

It describes the role of these notions in relation to the specification of a metamodel and a semantic

interpretation of annotations, with a view to defining a well-founded annotation scheme.

This part of ISO 24617 also provides guidelines for dealing with two issues regarding the annotation

schemes defined in SemAF-parts: a) conceptual and terminological inconsistencies that may arise due

to overlaps between annotation schemes and b) the treatment of semantic phenomena that cut across

SemAF-parts, such as negation, modality and quantification. Instances of both issues are identified, and

in some cases, direction is given as to how they may be tackled.

2 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

NOTE In addition, the terms ‘event’ and ‘eventuality’ are used (as synonyms) as defined in ISO 24617-1 as

something that can be said to obtain or hold true, to happen or to occur.

2.1

primary data

electronic representation of text or communicative behaviour

EXAMPLE Digital representations of text, transcriptions of speech, gestures or multimodal dialogue.

Note 1 to entry: ISO 24612 defines primary data as the ‘electronic representation of language data’. This definition

is unsatisfactory for this part of ISO 24617 as semantic annotation may relate to non-verbal or multimodal data,

such as stretches of spoken dialogue with accompanying gestures and facial expressions, and even gestures

and/or facial expressions without any accompanying speech.

2.2

annotation

linguistic information added to primary data (2.1), independent of its representation

[SOURCE: ISO 24612:2012, 2.3]

2.3

semantic annotation

annotation (2.2) which contains information about the meaning of a segment or region of primary data

(2.1)

2.4

metamodel

schematic representation of the concepts that are used in the analysis and description of the phenomena

covered in annotations (2.2) and of the relationships between them

3 Purpose and motivation

3.1 Purpose

The purpose of this part of ISO 24617 is to provide support for the establishment of a consistent and

coherent set of international standards for semantic annotation within the Semantic Annotation

Framework (SemAF). It aims to do so in three ways.

First, by making explicit which basic principles underlie the approach that has been followed in

defining international standards in the SemAF parts that have been published so far (ISO 24617-1 and

ISO 24617-2, ISO 24617-4 and ISO 24617-7), and in parts that are close to publication (ISO 24617-6)

or in preparation (ISO 24617-8). This approach provides the Semantic Annotation Framework with

methodological coherence and helps to ensure mutual consistency between existing, developing, and

future SemAF parts.

Second, by identifying overlaps between SemAF parts and indicating how such overlaps may be dealt

with. Examples are the occurrence of temporal and spatial relations among semantic roles and of

discourse relations between dialogue acts.

Third, by identifying common issues that arise in various parts of SemAF (they are only partly covered

in these parts, if they are covered at all) and, where possible, by giving directions as to how these issues

may be tackled. Examples of such issues are polarity, modality, quantification, measures, qualification,

veridicity, attribution and non-literal language use.

3.2 Motivation

Semantic annotation enhances primary data with information about their meaning. The state of the art

in computational semantics makes it unlikely that a single existing formalism for annotating semantic

information would receive wide support from researchers and developers. Moreover, semantic

annotation tasks often have the limited aim of annotating certain specific semantic phenomena,

such as semantic roles, discourse relations or coreference relations, rather than annotating the full

meaning of stretches of primary data. A strategy was therefore adopted in ISO TC 37/SC 4 to devise the

SemAF standards in different parts, with separate annotation schemes for those classes of semantic

phenomenon for which the state of the art would justify the establishment of annotation standards;

these schemes could be extended and combined over time, growing into a wide-coverage framework for

semantic annotation.

This ‘crystal growth’ strategy has contributed significantly to the progress made in establishing

standardized annotation concepts and schemes supporting the development of interoperable resources,

but it also entails certain risks:

a) the annotation schemes defined in different SemAF parts are not necessarily mutually consistent,

especially in the case of overlaps in scope;

b) it may not be possible to combine the schemes, defined in different parts, into a coherent single

scheme with a wider coverage if they incorporate different views or employ different methodologies;

c) some semantic phenomena do not belong to the scope of any SemAF parts but cannot be disregarded

entirely in some parts, and this may result in these phenomena being unsatisfactorily treated.

The methodological principles and guidelines provided in this part of ISO 24617 are designed to

minimize these risks.

2 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

With regard to the issue of mutual consistency between SemAF parts, it may be noted that ISO 24617-1

for annotating time and events and ISO 24617-2 for annotating dialogue acts are concerned with

sufficiently distinct kinds of semantic information to allow their definitions to be established

independently. Other SemAF parts, such as those concerned with semantic roles, with relations in

discourse and with spatial information show a certain amount of overlap in the information that they

aim to capture, and the question therefore arises: can we ensure that the annotation schemes, defined

in these parts, are mutually consistent?

Mutual consistency of SemAF parts relates to the possible integration of annotation schemes defined

in different parts. For example, it would be desirable to use the ISO 24617-1 scheme (“ISO-TimeML”) for

annotating time and events in combination with the ISO 24617-4 scheme for semantic roles, thereby

annotating coherently not only the events identified in the data with their temporal properties, but

also the way in which these events are related to their participants. Integrating these annotations with

those of spatial information, using the ISO 24617-7 scheme for spatial information, would be another

plausible and desirable step, given that time and space are intertwined with concepts relating to motion

and velocity. More generally, the integration of SemAF parts would greatly enhance the significance

of the individual parts; in the end, SemAF’s ‘crystal growth’ strategy of SemAF is only really useful

if the annotation schemes defined in the various parts can grow into a single scheme with a wide

coverage of semantic phenomena. Only then can it effectively support such applications as text-based

question answering or extracting semantic information from text, and form the basis for automatically

recognizing semantic phenomena by means of machine-learning techniques. Clearly, this is only possible

if the annotation schemes are mutually consistent (e.g. they use the same classification of event types),

and are coherent whether, for example, temporal and spatial objects are viewed as event participants

or as the circumstances of an event.

With regard to the risk of unsatisfactory partial treatments of phenomena that are not among the

core issues of any (current) SemAF part, it should be noted that some of these phenomena cut across

several of these parts and are important for semantics-driven applications. Negation, or more generally

negative polarity, and quantification are two cases in point. Given that the aim in ISO-TimeML, for

instance, is to support the annotation of events, of their relation to time, and of the temporal relations

among temporal objects, it is desirable to be able to deal with sentences like the following:

(1) John teaches every Monday.

(2) Mary called twice this morning.

(3) John rang home twice a day.

Sentence (1) is about a set of “teach” events, each of which is related to a different element of the set of

temporal objects that are called “Monday”, so this is a case of quantification involving two sets, a set of

events and sets of days. Similarly, sentence (2) about a set of two “call” events, both related to the same

period of time. Sentence (3) is about a set of events and their frequency of occurrence.

In order to deal with such phenomena, ISO-TimeML has certain provisions for annotating quantification,

[13]

but they are not really adequate and do not generalize to cases of quantification where no events

are involved.

4 Overview

The ISO efforts aiming to develop standards for semantic annotation rest on certain basic principles,

some of which have been laid out by Reference [14] as requirements for semantic annotation, and

have been developed further in Reference [5]; others have been formulated as general principles for

linguistic annotation and are part of the ISO Linguistic Annotation Framework (LAF; see Reference [18]

and ISO 24623-1). The two sets of principles and requirements are considered in Clause 5.

The three kinds of risk associated with the SemAF ‘crystal growth’ strategy that have been identified

above correspond to the following issues of consistency and completeness that arise in the design of

semantic annotation schemes within the SemAF framework.

Consistency among annotation schemes:

— methodological consistency: the same basic approach is followed with respect to the distinction

between abstract and concrete syntax and their interrelation, and with respect to their semantics;

— conceptual consistency: different schemes are based on compatible underlying views and ontological

assumptions regarding their basic concepts, as reflected in metamodels (e.g. verbs are viewed as

denoting states or events, rather than relations);

— terminological consistency: terms that occur in different annotation schemes have the same meaning

in every scheme and the same term is used across annotation schemes to indicate the same concept.

Completeness of a set of annotation schemes: the combination of multiple annotation schemes leads to

a scheme that

— covers a wide range of semantic phenomena,

— does not have significant gaps when covering the semantic phenomena that it aims to cover, and

— deals in a satisfactory way with semantic phenomena that cut across the combined schemes but

which do not belong to the core phenomena that any of the combined schemes are designed to cover.

Clause 5 describes the methodological framework for defining annotation schemes in SemAF parts,

thereby ensuring methodological consistency. Clause 6 discusses conceptual and terminological

consistency issues that arise due to overlaps between SemAF parts, while Clause 7 identifies issues of

completeness regarding the annotation of semantic phenomena that cut across existing SemAF parts.

5 Annotation principles and requirements

5.1 Principles inherited from the Linguistic Annotation Framework

The annotation of semantic information when using SemAF inherits the principles for linguistic

annotation as formulated in LAF. These principles are often of a very general nature; they include the

principle that relevant segments of primary data are referred to in a uniform and TEI-compliant way,

and the principle that different layers of annotation over the primary data can co-exist by using stand-

off annotation and a uniform way of cross-referencing between layers.

The latter principle, which concerns the distinction of layers of annotation enabled by a stand-off

representation format, is of particular relevance for SemAF because it allows different annotation

layers to be used for different types of semantic information; for example, one layer could be used for

the annotation of events, time and space, and another one could be used to annotate semantic roles.

In principle, this allows for the use not only of layers that are not mutually consistent, but also of

alternative annotations that employ different annotation schemes for the same phenomena. However,

the SemAF ‘crystal growth’ strategy is designed to ensure that the annotation schemes for the various

types of semantic information can grow into a coherent annotation scheme for a wide range of semantic

phenomena, and it is therefore highly undesirable to have inconsistencies between annotation layers

concerned with different SemAF parts.

[18]

Also of particular relevance for SemAF is the distinction between ‘annotations’ and ‘representations’.

An annotation is any item of linguistic information that is added to primary data, independently of any

particular representation format. A representation is a format into which an annotation is rendered,

for example as an XML expression. ISO standards are assumed to be defined at the level of annotations,

rather than representations. The fundamental distinction between annotations and representations has

prompted the development of a methodology for developing semantic annotation schemes that draws

a distinction between the ‘abstract syntax’ of annotations and the ‘concrete syntax’ of representations.

This methodology is described in Clause 6.

4 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

5.2 Other general annotation principles

In addition to the principles that SemAF inherits from LAF, other general principles for designing

annotation schemes (in particular as part of an ISO standard) are worth mentioning; most of these

emerged during the development of the ISO 24617-2 standard for dialogue act annotation.

a) Theoretical validity: Annotation standards should consolidate existing knowledge and

accordingly should be firmly rooted in theoretical studies of the annotated phenomena. Any concept

that may occur in annotations according to the standard should therefore be well established in the

scientific literature.

b) Empirical validity: Annotation standards are designed to be useful for annotating corpora of

recorded empirical data; the annotation scheme defined in a standard should not therefore include

theoretical constructs that are not found in such corpora, but only concepts that correspond to

phenomena that are observed in empirical data.

c) Learnability: For an annotation scheme to be useful in the construction of annotated language

resources, it should be possible both for human annotators and for automatic annotation systems

to effectively learn how to apply the scheme with acceptable precision.

d) Generalizability: ISO standards should not be restricted in their applicability to particular

languages, subject domains or applications.

e) Extensibility: While ISO standard annotation schemes are designed to be language-independent,

domain-independent and application-independent, some applications and some languages may

require specific concepts that are not relevant in other applications or languages. Annotation

schemes should therefore be open, that is to say, they should allow extension with language-

specific, domain-specific and application-specific concepts.

f) Completeness: An annotation standard is designed to provide a good coverage of the phenomena of

which it is designed to enable the annotation; the set of concepts defined in an annotation standard

should, in that sense, be complete.

g) Variable granularity: One way to achieve good coverage is to include annotation concepts of a

high level of generality and which cover many specific instances. Since an annotation scheme

which uses only very general concepts would not be optimally useful, this leads to the principle

that annotation schemes should include concepts with different levels of granularity. This is also

beneficial for its interoperability, as it provides more possibilities for conversion between existing

annotation schemes and the standard scheme.

h) Compatibility: In order to enable mappings between alternative annotation schemes and thereby

contribute to the interoperability of annotated resources, concepts that are commonly found in

existing annotation schemes should preferably be included in an annotation standard.

5.3 Principles specific to semantic annotation

The idea behind annotating a text, which dates from long before the digital era, is to add information to a

primary text in order to support its understanding. The semantic annotation of digital source texts has

a similar purpose, namely to support the understanding of the text by humans, as well as by machines.

An annotation that does not add any information would therefore seem to make little sense, but the

[39]

following example of the annotation of a temporal expression using TimeML seems to do just that:

NOTE 1 For simplicity, the annotations of the events that are mentioned in the previous sentence is

suppressed here.

(4)

The CEO announced that he would resign as of

the first of December 2008

In this annotation, the subexpression

adds to the noun phrase “the first of December 2008” the information that this phrase describes: the

date 2008-12-01.This does not add any information; rather, it paraphrases the noun phrase in TimeML.

This could be useful if the expression in the annotation language had a well-specified semantics that

could be used directly by computer programs for applications like information extraction and question

answering. Unfortunately, TimeML does not have a semantics.

NOTE 2 It would be very simple to provide a semantics for the XML fragment shown here but it would be very

difficult to do so for the whole of TimeML. See also 7.3.

A case where the annotation of a date as in the above example does add something is (5). From the

utterance “Mr Brewster called a staff meeting today”, it is impossible to know the date on which the event

that is mentioned took place; in this case, the annotation, which is identical to (4), would be informative.

NOTE 3 Note that the examples of TimeML annotations shown here are “old-fashioned” in the sense that the

TIMEX3 element is wrapped around the annotated string. Modern annotation methods (e.g. in ISO-TimeML) use

stand-off representations.

(5) Mr Brewster called a staff meeting today.

Mr Brewster called a staff meeting

today

The examples in (4) and (5) illustrate two different functions that semantic annotations may have:

interpreting a natural language expression by recoding it in a formal annotation language with a well-

defined semantics, and adding context information, in order to allow the interpretation of context-

dependent expressions.

A third function that semantic annotations may have is to make explicit how certain parts of an

utterance are semantically related; for example, this is the function of semantic role labelling and of

indicating semantic relations between sentences in a discourse when no such relation is mentioned.

Note that the first function presupposes annotations to have a well-defined semantics; the other two

functions do not presuppose this, but since semantic annotations in digital corpora are typically

designed to support interpretation and inference, a desideratum for all functions that a semantic

annotation may have is that it has a well-defined semantics. Semantic annotations, like other linguistic

annotations, may also serve the purpose of supporting linguistic research, such as identifying syntactic

and semantic patterns in sentences and texts.

These considerations lead to the following two principles for semantic annotation:

— Semantic additivity: semantic annotations add semantic information to source data, or re-express

certain source data in a formal representation.

— Semantic adequacy: semantic annotations should have a well-defined semantics, making the

annotations machine-interpretable.

6 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

6 The methodological basis of SemAF

6.1 Steps in the design of an annotation scheme

An annotation scheme determines which information may be added to primary data and how that

information is expressed. The design of an annotation scheme from scratch should begin with a

conceptual analysis of the information that the annotations should capture. This analysis identifies

the concepts that form the building blocks of annotations and specifies how these blocks may be

used to build annotation structures. This may be broken down into two steps, the first establishing a

conceptual view of the phenomena to be annotated, the second an articulation of this view in the form

of a formal specification of categories of entities and relations, and of how annotation structures can be

built up from elements in these categories. The first of these steps corresponds to what is known in ISO

projects as the establishment of a ‘metamodel’, that is to say, the expression of a conceptual view of the

phenomena to be annotated in the form of a (UML) diagram. The formal specification produced in the

second step constitutes the abstract syntax of an annotation language.

While these two steps make explicit what information can be captured in the annotations, they do not