ISO/TR 14073:2016

(Main)Environmental management — Water footprint — Illustrative examples on how to apply ISO 14046

Environmental management — Water footprint — Illustrative examples on how to apply ISO 14046

ISO/TR 14073:2016 provides illustrative examples of how to apply ISO 14046, in order to assess the water footprint of products, processes and organizations based on life cycle assessment. The examples are presented to demonstrate particular aspects of the application of ISO 14046 and therefore do not present all of the details of an entire water footprint study report as required by ISO 14046. NOTE The examples are presented as different ways of applying ISO 14046 and do not preclude alternative ways of calculating the water footprint, provided they are in accordance with ISO 14046.

Management environnemental — Empreinte eau — Exemples illustrant l'application de l'ISO 14046

General Information

- Status

- Withdrawn

- Publication Date

- 18-Aug-2016

- Withdrawal Date

- 18-Aug-2016

- Technical Committee

- ISO/TC 207/SC 5 - Life cycle assessment

- Drafting Committee

- ISO/TC 207/SC 5 - Life cycle assessment

- Current Stage

- 9599 - Withdrawal of International Standard

- Start Date

- 24-Aug-2016

- Completion Date

- 12-Feb-2026

Relations

- Consolidated By

ISO 13297:2020 - Small craft — Electrical systems — Alternating and direct current installations - Effective Date

- 06-Jun-2022

- Effective Date

- 03-Sep-2016

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

BSI Group

BSI (British Standards Institution) is the business standards company that helps organizations make excellence a habit.

Bureau Veritas

Bureau Veritas is a world leader in laboratory testing, inspection and certification services.

DNV

DNV is an independent assurance and risk management provider.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO/TR 14073:2016 is a technical report published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Environmental management — Water footprint — Illustrative examples on how to apply ISO 14046". This standard covers: ISO/TR 14073:2016 provides illustrative examples of how to apply ISO 14046, in order to assess the water footprint of products, processes and organizations based on life cycle assessment. The examples are presented to demonstrate particular aspects of the application of ISO 14046 and therefore do not present all of the details of an entire water footprint study report as required by ISO 14046. NOTE The examples are presented as different ways of applying ISO 14046 and do not preclude alternative ways of calculating the water footprint, provided they are in accordance with ISO 14046.

ISO/TR 14073:2016 provides illustrative examples of how to apply ISO 14046, in order to assess the water footprint of products, processes and organizations based on life cycle assessment. The examples are presented to demonstrate particular aspects of the application of ISO 14046 and therefore do not present all of the details of an entire water footprint study report as required by ISO 14046. NOTE The examples are presented as different ways of applying ISO 14046 and do not preclude alternative ways of calculating the water footprint, provided they are in accordance with ISO 14046.

ISO/TR 14073:2016 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 13.020.10 - Environmental management; 13.020.60 - Product life-cycles. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO/TR 14073:2016 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to ISO 13297:2020, ISO/TR 14073:2017. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

ISO/TR 14073:2016 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

TECHNICAL ISO/TR

REPORT 14073

First edition

2016-09-01

Environmental management — Water

footprint — Illustrative examples on

how to apply ISO 14046

Management environnemental — Empreinte eau — Exemples

illustrant l’application de l’ISO 14046

Reference number

©

ISO 2016

© ISO 2016, Published in Switzerland

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior

written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of

the requester.

ISO copyright office

Ch. de Blandonnet 8 • CP 401

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva, Switzerland

Tel. +41 22 749 01 11

Fax +41 22 749 09 47

copyright@iso.org

www.iso.org

ii © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

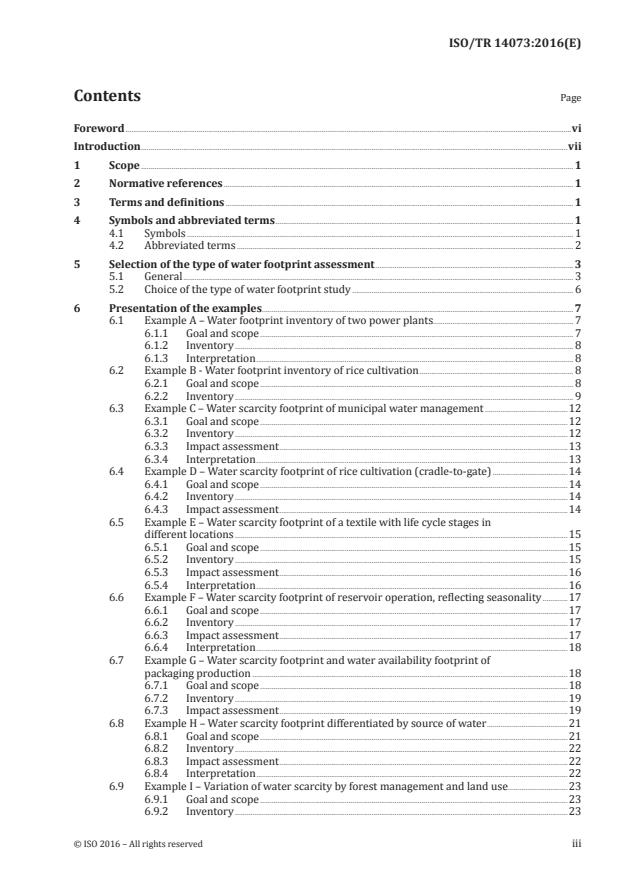

Contents Page

Foreword .vi

Introduction .vii

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Symbols and abbreviated terms . 1

4.1 Symbols . 1

4.2 Abbreviated terms . 2

5 Selection of the type of water footprint assessment . 3

5.1 General . 3

5.2 Choice of the type of water footprint study . 6

6 Presentation of the examples . 7

6.1 Example A – Water footprint inventory of two power plants. 7

6.1.1 Goal and scope . 7

6.1.2 Inventory . 8

6.1.3 Interpretation . 8

6.2 Example B - Water footprint inventory of rice cultivation . 8

6.2.1 Goal and scope . 8

6.2.2 Inventory . 9

6.3 Example C – Water scarcity footprint of municipal water management .12

6.3.1 Goal and scope .12

6.3.2 Inventory .12

6.3.3 Impact assessment .13

6.3.4 Interpretation .13

6.4 Example D – Water scarcity footprint of rice cultivation (cradle-to-gate) .14

6.4.1 Goal and scope .14

6.4.2 Inventory .14

6.4.3 Impact assessment .14

6.5 Example E – Water scarcity footprint of a textile with life cycle stages in

different locations .15

6.5.1 Goal and scope .15

6.5.2 Inventory .15

6.5.3 Impact assessment .16

6.5.4 Interpretation .16

6.6 Example F – Water scarcity footprint of reservoir operation, reflecting seasonality .17

6.6.1 Goal and scope .17

6.6.2 Inventory .17

6.6.3 Impact assessment .17

6.6.4 Interpretation .18

6.7 Example G – Water scarcity footprint and water availability footprint of

packaging production .18

6.7.1 Goal and scope .18

6.7.2 Inventory .19

6.7.3 Impact assessment .19

6.8 Example H – Water scarcity footprint differentiated by source of water .21

6.8.1 Goal and scope .21

6.8.2 Inventory .22

6.8.3 Impact assessment .22

6.8.4 Interpretation .22

6.9 Example I – Variation of water scarcity by forest management and land use .23

6.9.1 Goal and scope .23

6.9.2 Inventory .23

6.9.3 Impact assessment .23

6.9.4 Interpretation .24

6.10 Example J - Water eutrophication footprint of maize cultivation, calculated as one

or two indicator results .24

6.10.1 Goal and scope .24

6.10.2 Inventory .24

6.10.3 Impact assessment .25

6.11 Example K – Comprehensive water footprint profile of packaging production .27

6.11.1 Goal and scope .27

6.11.2 Inventory .27

6.11.3 Impact assessment .27

6.11.4 Interpretation .30

6.12 Example L – Non-comprehensive weighted water footprint of cereal cultivation .30

6.12.1 Goal and scope .30

6.12.2 Inventory .30

6.12.3 Impact assessment .30

6.13 Example M - Water footprint of packaging production as part of a life cycle assessment .32

6.13.1 Goal and scope .32

6.13.2 Inventory .32

6.13.3 Impact assessment .32

6.13.4 Interpretation .33

6.14 Example N – Non-comprehensive water footprint of textile production .33

6.14.1 Goal and Scope .33

6.14.2 Inventory .33

6.14.3 Impact assessment .34

6.14.4 Discussion .36

6.14.5 Limitations .36

6.15 Example O – Non-comprehensive weighted water footprint of municipal

water management .37

6.15.1 Goal and scope .37

6.15.2 Inventory .37

6.15.3 Impact assessment .38

6.15.4 Interpretation .40

6.16 Example P – Non-comprehensive water footprint of a company producing

chemicals (organization).41

6.16.1 Goal and scope .41

6.16.2 Inventory .42

6.16.3 Impact assessment .43

6.16.4 Interpretation .45

6.17 Example Q – Water scarcity footprint of an aluminium company (organization) .46

6.17.1 Goal and scope .46

6.17.2 Inventory .47

6.17.3 Impact assessment .47

6.17.4 Interpretation .51

6.18 Example R – Non-comprehensive direct water footprint of a hotel (organization)

considering seasonality .51

6.18.1 Goal and scope .51

6.18.2 Inventory .52

6.18.3 Impact assessment .52

6.18.4 Interpretation .53

7 Issues arising in water footprint studies .53

7.1 Seasonality .53

7.2 Use of a baseline .54

7.3 Evaporation, transpiration and evapotranspiration .55

7.4 Water quality .55

7.4.1 General.55

7.4.2 Relevant air and soil (and water) emissions .56

7.5 Choice of indicators along the environmental mechanism .57

iv © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

7.6 Identification of foreseen consequences of the excluded impacts .58

7.7 Sensitivity analysis .58

Bibliography .60

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation on the meaning of ISO specific terms and expressions related to conformity assessment,

as well as information about ISO’s adherence to the World Trade Organization (WTO) principles in the

Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) see the following URL: www.iso.org/iso/foreword.html.

The committee responsible for this document is Technical Committee ISO/TC 207, Environmental

management, Subcommittee SC 5, Life cycle assessment.

vi © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

Introduction

Principles, requirements and guidelines for the quantification and reporting of a water footprint are

given in ISO 14046. The water footprint assessment according to ISO 14046 can be conducted as a

stand-alone assessment, where only impacts related to water are assessed, or as part of a life cycle

assessment. In addition, a variety of modelling choices and approaches are possible depending on the

goal and scope of the assessment. The water footprint can be reported as a single value or as a profile of

impact category indicator results.

This document provides illustrative examples on the application of ISO 14046 to further enhance

understanding of ISO 14046 and to facilitate its widespread application.

At the time of the publication of this document, water footprint assessment methods are developing

rapidly. Practitioners are encouraged to be aware of the latest developments when undertaking water

footprint studies.

These examples are for illustrative purposes only and some of the data used are fictitious. The data are

not intended be used outside of the context of this document.

The Bibliography might contain references to methods that are not fully compliant with ISO 14046:2014.

TECHNICAL REPORT ISO/TR 14073:2016(E)

Environmental management — Water footprint —

Illustrative examples on how to apply ISO 14046

1 Scope

This document provides illustrative examples of how to apply ISO 14046, in order to assess the water

footprint of products, processes and organizations based on life cycle assessment.

The examples are presented to demonstrate particular aspects of the application of ISO 14046 and

therefore do not present all of the details of an entire water footprint study report as required by

ISO 14046.

NOTE The examples are presented as different ways of applying ISO 14046 and do not preclude alternative

ways of calculating the water footprint, provided they are in accordance with ISO 14046.

2 Normative references

The following documents are referred to in the text in such a way that some or all of their content

constitutes requirements of this document. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For

undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 14046:2014, Environmental management — Water footprint — Principles, requirements and guidelines

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions given in ISO 14046:2014 apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at http://www.iso.org/obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at http://www.electropedia.org/

4 Symbols and abbreviated terms

4.1 Symbols

α characterization factor

C concentration

E emission

F footprint

R rainfall

V volume

4.2 Abbreviated terms

1,4-DB 1,4-Dichlorobenzene

2,4-D 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

APSIM Agricultural Production Systems sIMulator

BOD Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD5 means “measured during 5 days”)

CF Characterization Factor

COD Chemical Oxygen Demand

CTU Comparative Toxic Unit

NOTE 1 “CTU ” for ecosystems; “CTU ” for humans; “CTU ” for cancer; “CTU ” for

e h c n-c

non-cancer.

CWU Consumptive Water Use

CWV Critical Water Volume

DALY Disability Adjusted Life Years

DWU Degradative Water Use

DWCM-AgWU Distributed Water Circulation Model Incorporating Agricultural Water Use

ET Evapotranspiration

FU Functional Unit

H O-eq Water “equivalent”

NOTE 2 Typical unit to express the impact score associated with water scarcity. Some-

times the term H O-eq is written H O eq, or H Oe.

2 2 2

LCA Life Cycle Assessment

LCI Life Cycle Inventory

LCIA Life Cycle Impact Assessment

OEF Organization Environmental Footprint

PEF Product Environmental Footprint

PDF Potentially Disappeared Fraction of species

PAF Potentially Affected Fraction of species

RU Reporting Unit

TOC Total Organic Carbon

WSI Water Scarcity Index

2 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

NOTE 3 Sometimes the term water stress index (also abbreviated as WSI) is used in the

literature for what is termed a water scarcity index in this document.

WSF Water Scarcity Footprint

WULCA Water Use in LCA

5 Selection of the type of water footprint assessment

5.1 General

The water footprint assessment conducted according to ISO 14046 can be:

— a stand-alone assessment where only impacts related to water are assessed;

— a part of a life cycle assessment (LCA) where consideration is given to a comprehensive set of

environmental impacts, which are not only impacts related to water.

Table 1 lists the illustrative examples in this document and the different topics that are highlighted in

each example.

Table 1 — Types of water footprint assessment shown in the examples

Product/

Case study Impact

process or Topic highlight- Type of footprint System

Example used in the assessment

a a

organization ed boundary

a

example method

focus

n/a (Water foot-

Product/ Water footprint n/a (inventory

A Power plant print inventory Gate-to-gate

Process inventory only)

only)

Water footprint n/a (Water foot-

Product/ Rice cultiva- n/a (inventory

B inventory using a print inventory Gate-to-gate

Process tion only)

baseline only)

Boulay et al.

Option com- Municipal

Product/ Water scarcity

(2016) (WU

C parison using water manage- Gate-to-gate

Process footprint

scarcity ment

[5]

LCA)

Application of Ridoutt and

Product/ Water scarcity

D water scarcity Rice Gate-to-gate Pfister (2010)

Process footprint

[6]

footprint method

Boulay et

al. (2016)

(WULCA)

[5]

; Pfister et

[7]

al. (2009) ;

Frischknecht

et al. (2008)

Influence of im-

[8]

; EU (2013)

Product/ pact assessment Water scarcity Cradle-to-

[9]

E Textile (PEF/OEF) ;

Process method chosen footprint grave

Boulay et al.

for scarcity

[10]

(2011a) ;

Hoekstra et al.

(2012) (Water

Footprint Net-

work - WFN)

[11]

; Berger et

[12]

al. (2014)

a

All examples explicitly or implicitly contain a water footprint inventory.

Table 1 (continued)

Product/

Case study Impact

process or Topic highlight- Type of footprint System

Example used in the assessment

a a

organization ed boundary

a

example method

focus

Pfister and

Product/ Reservoir Water scarcity

F Seasonality Gate-to-gate Bayer (2014)

Process operation footprint

[13]

Water scarcity

Product/ Scarcity vs avail- Packaging footprint; water Boulay et al.

G Gate-to-gate

[10]

Process ability production availability foot- (2011a)

print

Product/ Influence of Wheat cultiva- Water scarcity Yano et al.

H Gate-to-gate

[14]

Process water sources tion footprint (2015)

Influence of for-

Product/ Beer produc- Water scarcity Yano et al.

I est management Gate-to-gate

[14]

Process tion footprint (2015)

/ land use change

EU (2013)

[9]

(PEF/OEF) ;

Number of indi-

Product/ Water eutrophica- Cradle-to- Jolliet et al.

J cators per type Maize

Process tion footprint gate (2003) (IM-

of impact

PACT 2002+)

[15]

Bulle et

al. (2016)

(IMPACT

[16]

World+) ;

Rosenbaum

et al. (2008)

[17]

(USEtox) ;

Guinée et

[19]

al. 2001 ;

Water footprint

EU (2013)

Product/ Comprehensive Packaging Cradle-to-

K (comprehensive

(PEF/OEF)

Process water footprint product gate

profile) [9]

; Verones

et al. (2011)

[19]

; Boulay

et al. (2016)

[5]

(WULCA) ;

Boulay et al.

[9]

(2011a) ;

Hannafiah et

[20]

al. (2011)

Goedkoop

et al. (2009)

[21]

(ReCiPe) ;

Applying weight- Non-comprehen-

Product/ Cereal cultiva- Ridoutt and

L ing to obtain a sive weighted Gate-to-gate

Process tion Pfister (2010)

single value water footprint

[6]

; Ridoutt

and Pfister

[22]

(2013)

a

All examples explicitly or implicitly contain a water footprint inventory.

4 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

Table 1 (continued)

Product/

Case study Impact

process or Topic highlight- Type of footprint System

Example used in the assessment

a a

organization ed boundary

a

example method

focus

Boulay et

al. (2016)

[5]

(WULCA)

Product/ Water footprint Packaging Water footprint as Cradle-to-

(Water

M

Process as part of an LCA product part of an LCA gate

degradation

footprint

profile already

present)

Hoekstra et

Non-compre- al. (2012);

Product/ Cradle-to-

N Seasonality Textile product hensive water (Water Foot-

Process gate

footprint print Network

[11]

- WFN)

Pfister et al.

[7]

(2009) ;

Ridoutt and

Pfister (2013)

[22]

;

Goedkoop et

Applying weight- Municipal Non-comprehen-

al., (2009)

Product/ Cradle-to-

O ing to obtain to water manage- sive weighted

(ReCiPe)

Process grave

single value ment water footprint

[21]

; Jolliet

et al. (2003)

(IMPACT

[15]

2002+) ;

Rosenbaum

et al. (2008)

[17]

(USEtox)

Berger et al.

Applying water Non-compre-

[12]

Chemical pro- (2014) ;

P Organization footprint to dif- hensive water Gate-to-gate

duction Saling et al.

ferent sites footprint

[23]

(2002)

Applying water

footprint to Aluminium Water scarcity Cradle-to- Pfister et al.

Q Organization

[7]

supply chain of a production footprint gate (2009)

company

Boulay et

al. (2016)

[5]

(WULCA) at

Applying water Non-compre-

the monthly

Hotel opera-

R Organization footprint to a ser- hensive water Gate-to-gate

approach;

tion

vice company footprint

Goedkoop

et al. (2009)

[21]

(ReCiPe)

a

All examples explicitly or implicitly contain a water footprint inventory.

NOTE 1 Guidance about application of LCA to organizations is given in ISO/TS 14072. In addition,

ISO 14046:2014, Annex A, provides guidelines for water footprint assessment of organizations.

NOTE 2 The principles of comprehensiveness for an LCA study and for a water footprint assessment are

different (see ISO 14040:2006, 4.1.7, and ISO 14046:2014, 4.13).

NOTE 3 The term “partial” is sometimes used as a synonym for “non-comprehensive”. However, “partial” is

avoided in this document as it is also used with a different meaning, such as in ISO/TS 14067.

5.2 Choice of the type of water footprint study

The different types of water footprint are defined in ISO 14046:2014, 5.4.5 to 5.4.7. The choice of a

particular type of water footprint to be assessed in a stand-alone water footprint study is determined

in the goal and scope definition phase.

In addition to the goal of the study (see ISO 14046:2014, 5.2.1) the choice of type of water footprint may

be influenced by consideration of an appropriate system boundary, the type(s) of water resource used

and affected water resources, the associated changes in water quantity and quality and determination

of relevant impact assessment categories and methodologies.

Figure 1 illustrates a procedure for choosing the type of water footprint for a stand-alone water

footprint study.

Figure 1 — Procedure for choosing the type of a water footprint assessment for a stand-alone

water footprint study

The procedure for choosing an appropriate system boundary in a water footprint study as defined in

ISO 14046:2014, 3.3.8, can be supported by collation of additional information such as:

— developing a map showing the geographical location of each unit process;

— identification of the unit processes that are located in areas of critical water availability (taking into

account relevant seasonal and temporal variability);

— identification of the unit processes with air, water and soil emissions that can potentially affect

ecologically vulnerable water bodies.

All water inputs and outputs relevant to the system (see examples in Figure 2) are considered for

relevant changes in water quantity (volume) and water quality parameters and/or characteristics,

including emissions to air, water and soil that affect water quality. Estimates may be based on readily

available data or models.

6 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

Figure 2 — Examples of water inputs (left) and outputs (right) for a unit process under study

In addition to the goal of the water footprint study, the information collected in order to define the

system boundary, the type(s) of water resource used and affected water resources, and the associated

(quantitative and/or qualitative) changes in water, can assist in determining the appropriate impact

categories, category indicators and the characterization models to be considered for the water

footprint study – and therefore choice of a type of water footprint. Based on the information collected,

it is possible to:

— estimate the degree of likely significance (i.e. potential contribution to the water footprint) of each

unit process for the study, and therefore which unit processes should become the focus for more

detailed data collection;

— specify the data requirements (e.g. primary data, secondary data, estimated data) based on the

likely significance of each unit process for the water footprint;

— define the initial cut-off criteria for the study (which are revisited throughout the study following

ISO 14046:2014, 4.5).

Based on this information and general information related to the goal of the study (see ISO 14046:2014,

5.2.1) the type of water footprint that will be a result of the water footprint study can be chosen.

6 Presentation of the examples

6.1 Example A – Water footprint inventory of two power plants

6.1.1 Goal and scope

This example illustrates the compilation of water flows and emissions affecting water of a unit process.

A utility wanting to evaluate which of two planned options has the lowest direct water footprint starts

by creating the direct water footprint inventory of both options, from a gate-to-gate perspective.

This direct water footprint inventory can then be used in combination with water footprint impact

assessment methods, considering water scarcity footprint and/or water degradation footprint, to

evaluate the direct water footprint of both options.

NOTE The term “direct” is used as “what happens on the site” (see ISO 14046:2014, 3.5.14) (gate-to-gate,

excluding any inputs such as infrastructure production, maintenance and outputs such as electricity). The term

“indirect” is used for background processes (see ISO 14046:2014, 3.5.15).

6.1.2 Inventory

Table 2 shows the water footprint inventory associated with both options. The inventory is based on

collected and modelled data and expressed per kWh of electricity produced.

Table 2 — Gate-to-gate water footprint inventory associated with two power plants options

Option 2

Option 1

Unit

(power plant, situated in a

(power plant, situated in a

Flows

(per kWh location B, with lower river

location A, using through

produced) flow and therefore using a

flow without cooling tower)

cooling tower)

Address of the power plant — AA BB

— Location A (name of the Location B (name of the

Location country and if possible country and if possible

drainage basin) drainage basin)

— Assumed to be a constant Assumed to be a constant

Temporal variation

use of water use of water

Water withdrawal l 40 10

Water release l 38 6

Temperature of water released °C 25 25

Water consumed l 2 4

Chromium (III) emitted to water g 0,001 0,001

Oil emitted to water g 0,02 0,02

SO emitted to air g 0,7 0,7

NO emitted to air g 0,6 0,6

x

Mercury emitted to air mg 0,04 0,04

Dioxin, 2,3,7,8, Tetrachlorodibenzo-p- ng 0,07 0,07

More if available … … …

6.1.3 Interpretation

Such an inventory can be as extensive as needed to capture all emissions (as well as other information)

useful to apply the impact assessment methods that will be chosen in the study. The quality of the data

is sometimes specified in order to provide information about the accuracy of the water footprint that

will be calculated based on this inventory. The naming of the flows in the inventory is matched with the

naming of the flows in the impact assessment.

From the address of the power plants, the data of the location (e.g. the water scarcity index) can be

determined within a subsequent impact assessment using satellite imagery. As the water scarcity

footprint of both locations can be very different, comparison between both options on the inventory

level can be misleading.

6.2 Example B - Water footprint inventory of rice cultivation

6.2.1 Goal and scope

This example illustrates calculation of water flows based on the hydrology of an area.

This example is not a traditional LCA case study, but it illustrates a special case, considering non-

irrigated paddies as the baseline.

The example is shown as an exercise of a non-comprehensive water footprint inventory by utilizing

existing hydrological knowledge, namely the usage of a hydrological model to analyse water footprint

inventory of unit processes.

8 © ISO 2016 – All rights reserved

This example refers to rice cultivation, as an example of a water footprint inventory analysis, in a

country in monsoon Asia with moderate rainfall and suitable rice cultivation practices. An irrigated

area lies downstream of the intake facility (Figure 3) and the baseline land use is rainfed (i.e. non-

irrigated) rice.

This is a “gate-to-gate” example. For the purpose of this example, energy and goods required for rice

cultivation are excluded.

Figure 3 — Depiction of basin-wide processes

6.2.2 Inventory

The elementary flows are quantified by utilizing a hydrological model, such as DWCM-AgWU (Yoshida et

[24] [25]

al. 2012 ; Masumoto et al. 2009 ), at the scale of drainage basins. Agricultural situations typically

require modelling because it is difficult, or even impossible, to measure all the elementary flows.

The elementary flows quantified in the water footprint inventory can be used to determine the water

scarcity footprint which is described in other examples. In order to determine the water availability

footprint, the water degradation footprint or a water footprint profile, other elementary flows related

to water quality need to be determined.

6.2.2.1 Elementary flows

In this approach, a single process in an agricultural area receives rainfall, irrigation and residual water

(water that has not been diverted from the river for the intention to irrigate this area; inflow locations)

as inputs, and have evaporation, transpiration, percolation to groundwater and return flow to the river

as outputs (Figure 4).

Furthermore, it is shown that all input water is withdrawn from the location of the process and all

output water is released to the location of the process. Part of water output as groundwater gradually

returns back into the river systems or is utilized as the source of public water supply.

In paddy areas, the source of freshwater differs between rainfed (precipitation) and irrigated

paddies (irrigation water). In both cases, various types of water use exist, such as three types in

rainfed agriculture (only rainfall, rainfall plus supplementary water stored in small ponds, and using

flooding water) and six categories in irrigated paddies (gravity-fed water, pumped water, reservoirs,

impounding of silty water (colmatage), release of river water into coastal wetlands and near-shore

waters by managing controlling tides, and groundwater).

NOTE 1 Upwelling flow is defined as part of seepage NOTE 2 The irrigated area is delineated for the

returning to the surface from the ground within an DWCM-AgWU.

irrigated area.

a) Water balance b) Inflow and outflows in an irrigated area

Figure 4 — Schematics of the calculation for hydrological components and river return ratio

6.2.2.2 Calculation procedure of water footprint inventory

The water footprint inventory is determined as follows:

a) the estimation in water footprint inventory of unit process for rice cultivation in paddy areas is

carried out at the scale of the irrigated area;

b) each elementary flow is modelled using DWCM-AgWU, which comprises water allocation and

management, evapotranspiration, planting time/area (rice phenology), paddy water use and runoff

[24] [25]

models (Yoshida et al. 2012 ; Masumoto et al. 2009 );

c) the water balance of the baseline situation is calculated assuming no irrigation is carried out.

NOTE In the paddy-dominant areas with two or three crops within a year, paddies are classified into rainfed

in rainy seasons and irrigated in dry season. As for the baseline situation, it is assumed that an irrigation system

is not introduced, so paddies are regarded as rainfed types.

These results are then summed across the basin (an example in one region of the basin; Table 3) and

3 3

expressed in the units m per ha per irrigation period, or m per kg brown rice for example.

6.2.2.3 Input parameters and calculated results of unit processes

Input parameters into the DWCM-AgWU model are land use data, meteorological data, geological and

geomorphologic data, and celled basin data. The model estimates the planting area of paddies, intake

amount and soil moistur

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...