IEC 60076-10-1:2016

(Main)Power transformers - Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels - Application guide

Power transformers - Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels - Application guide

IEC 60076-10-1:2016 provides supporting information to help both manufacturers and purchasers to apply the measurement techniques described in IEC 60076-10. Besides the introduction of some basic acoustics, the sources and characteristics of transformer and reactor sound are described. Practical guidance on making measurements is given, and factors influencing the accuracy of the methods are discussed. This application guide also indicates why values measured in the factory may differ from those measured in service. This application guide is applicable to transformers and reactors together with their associated cooling auxiliaries. This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous edition:

a) extended information on sound fields provided;

b) effect of current harmonics in windings enfolded;

c) updated information on measuring methods sound pressure and sound intensity given;

d) supporting information on measuring procedures walk-around and point-by-point given;

e) clarification of A-weighting provided;

f) new information on frequency bands given;

g) background information on measurement distance provided;

h) new annex on sound-built up due to harmonic currents in windings introduced.

This publication is to be read in conjunction with IEC 60076-10:2016.

Transformateurs de puissance - Partie 10-1: Détermination des niveaux de bruit - Guide d'application

L'IEC 60076-10-1:2016 fournit des informations visant à aider les fabricants et les acheteurs à appliquer les techniques de mesure décrites dans l'IEC 60076-10. Outre l'introduction de certaines notions acoustiques de base, les sources et caractéristiques relatives aux transformateurs et aux bobines d'inductance sont décrites. Des lignes directrices pratiques relatives aux mesures sont fournies, et les facteurs exerçant une influence sur la précision des méthodes sont abordés. Le présent guide d'application indique également pourquoi les valeurs mesurées en usine peuvent différer de celles mesurées en service. Le présent guide d'application s'applique aux transformateurs et aux bobines d'inductance ainsi qu'à leurs auxiliaires de refroidissement associés. Cette édition inclut les modifications techniques majeures suivantes par rapport à l'édition précédente:

a) ajout d'informations étendues relatives aux champs acoustiques;

b) intégration de l'effet des harmoniques réels sur les enroulements;

c) ajout d'informations mises à jour sur les méthodes de mesure en pression acoustique et sur l'intensité acoustique;

d) informations à l'appui relatives aux procédures de mesure d'inspection en continu et point par point;

e) ajout d'une clarification de la pondération A;

f) ajout de nouvelles informations sur les bandes de fréquence;

g) ajout d'informations de contexte sur la distance de mesure;

h) introduction d'une nouvelle annexe sur l'augmentation acoustique due aux courants harmoniques dans les enroulements.

Cette publication doit être lue conjointement avec la IEC 60076-10:2016.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 23-Mar-2016

- Technical Committee

- TC 14 - Power transformers

- Drafting Committee

- MT 60076-10 - TC 14/MT 60076-10

- Current Stage

- PPUB - Publication issued

- Start Date

- 24-Mar-2016

- Completion Date

- 15-May-2016

Relations

- Effective Date

- 05-Sep-2023

- Effective Date

- 05-Sep-2023

Overview

IEC 60076-10-1:2016 - Power transformers – Part 10‑1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide is an IEC application guide that supports manufacturers and purchasers in applying the measurement techniques given in IEC 60076-10. It explains basic acoustics, describes the sources and characteristics of transformer and reactor sound (including cooling auxiliaries), and gives practical guidance on making sound measurements and interpreting results. This edition incorporates amendment changes (2020) that extend guidance on sound fields, harmonics, measurement methods and procedures, A‑weighting, frequency bands, and measurement distance.

Key topics and technical content

- Basic acoustics: sound pressure, particle velocity, sound intensity and sound power; near-field, far-field and diffuse-field concepts.

- Sources of transformer/reactor noise: core magnetostriction, winding forces, stray-flux control elements, fans and pumps; effects of current harmonics and DC bias.

- Measurement methods: detailed practical guidance on sound pressure and sound intensity methods, including microphone arrangements, spacer selection and handling for reliable readings.

- Measurement procedures: supported procedures such as walk‑around and point‑by‑point approaches, with advice on avoiding standing waves and other artefacts.

- Frequency analysis: guidance on relevant frequency bands and transformer tones (including A‑weighting clarification) for accurate assessment.

- Factory vs field differences: explanation why measured values can differ between factory tests and in‑service measurements (operating voltage, load current, harmonics, reflections, temperature, remanent flux, auxiliaries).

- Harmonic effects: new annex and background on sound build‑up due to harmonic currents in windings and how harmonics influence tonal content and levels.

Practical applications

- Performing and specifying accurate power transformer noise measurements for type tests, acceptance tests and field audits.

- Diagnosing dominant sound sources (core, winding, fans) to support design improvements, mitigation or compliance with acoustic limits.

- Comparing factory and site sound levels and explaining discrepancies for purchasers and utilities.

- Guiding acoustic consultants, test engineers and manufacturers on best practices for measurement setup, frequency band selection and reporting.

Who should use this standard

- Transformer and reactor manufacturers, purchasers, and utilities

- Test engineers, acoustic consultants, and certification bodies involved in noise assessment

- Design teams addressing noise control and compliance with environmental or contractual sound limits

Related standards

- Read in conjunction with IEC 60076-10:2016 (main measurement standard).

- Refer also to relevant international acoustic measurement standards and local regulations when specifying test methods and reporting requirements.

Keywords: IEC 60076-10-1:2016, power transformers, transformer noise, sound levels, sound pressure, sound intensity, A‑weighting, harmonic currents, measurement procedures, transformer sound measurement.

IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV - Power transformers - Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels - Application guide Released:11/2/2020

IEC 60076-10-1:2016 - Power transformers - Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels - Application guide

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

Intertek Testing Services NA Inc.

Intertek certification services in North America.

UL Solutions

Global safety science company with testing, inspection and certification.

ANCE

Mexican certification and testing association.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

IEC 60076-10-1:2016 is a standard published by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Its full title is "Power transformers - Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels - Application guide". This standard covers: IEC 60076-10-1:2016 provides supporting information to help both manufacturers and purchasers to apply the measurement techniques described in IEC 60076-10. Besides the introduction of some basic acoustics, the sources and characteristics of transformer and reactor sound are described. Practical guidance on making measurements is given, and factors influencing the accuracy of the methods are discussed. This application guide also indicates why values measured in the factory may differ from those measured in service. This application guide is applicable to transformers and reactors together with their associated cooling auxiliaries. This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous edition: a) extended information on sound fields provided; b) effect of current harmonics in windings enfolded; c) updated information on measuring methods sound pressure and sound intensity given; d) supporting information on measuring procedures walk-around and point-by-point given; e) clarification of A-weighting provided; f) new information on frequency bands given; g) background information on measurement distance provided; h) new annex on sound-built up due to harmonic currents in windings introduced. This publication is to be read in conjunction with IEC 60076-10:2016.

IEC 60076-10-1:2016 provides supporting information to help both manufacturers and purchasers to apply the measurement techniques described in IEC 60076-10. Besides the introduction of some basic acoustics, the sources and characteristics of transformer and reactor sound are described. Practical guidance on making measurements is given, and factors influencing the accuracy of the methods are discussed. This application guide also indicates why values measured in the factory may differ from those measured in service. This application guide is applicable to transformers and reactors together with their associated cooling auxiliaries. This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous edition: a) extended information on sound fields provided; b) effect of current harmonics in windings enfolded; c) updated information on measuring methods sound pressure and sound intensity given; d) supporting information on measuring procedures walk-around and point-by-point given; e) clarification of A-weighting provided; f) new information on frequency bands given; g) background information on measurement distance provided; h) new annex on sound-built up due to harmonic currents in windings introduced. This publication is to be read in conjunction with IEC 60076-10:2016.

IEC 60076-10-1:2016 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 29.180 - Transformers. Reactors. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

IEC 60076-10-1:2016 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to IEC 60076-10-1:2016/AMD1:2020, IEC 60076-10-1:2005. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

IEC 60076-10-1:2016 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

IEC 60076-10-1 ®

Edition 2.1 2020-11

CONSOLIDATED VERSION

INTERNATIONAL

STANDARD

colour

inside

Power transformers –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from

either IEC or IEC's member National Committee in the country of the requester. If you have any questions about IEC

copyright or have an enquiry about obtaining additional rights to this publication, please contact the address below or

your local IEC member National Committee for further information.

IEC Central Office Tel.: +41 22 919 02 11

3, rue de Varembé info@iec.ch

CH-1211 Geneva 20 www.iec.ch

Switzerland

About the IEC

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is the leading global organization that prepares and publishes

International Standards for all electrical, electronic and related technologies.

About IEC publications

The technical content of IEC publications is kept under constant review by the IEC. Please make sure that you have the

latest edition, a corrigendum or an amendment might have been published.

IEC publications search - webstore.iec.ch/advsearchform Electropedia - www.electropedia.org

The advanced search enables to find IEC publications by a The world's leading online dictionary on electrotechnology,

variety of criteria (reference number, text, technical containing more than 22 000 terminological entries in English

committee,…). It also gives information on projects, replaced and French, with equivalent terms in 16 additional languages.

and withdrawn publications. Also known as the International Electrotechnical Vocabulary

(IEV) online.

IEC Just Published - webstore.iec.ch/justpublished

Stay up to date on all new IEC publications. Just Published IEC Glossary - std.iec.ch/glossary

details all new publications released. Available online and 67 000 electrotechnical terminology entries in English and

once a month by email. French extracted from the Terms and definitions clause of

IEC publications issued between 2002 and 2015. Some

IEC Customer Service Centre - webstore.iec.ch/csc entries have been collected from earlier publications of IEC

If you wish to give us your feedback on this publication or TC 37, 77, 86 and CISPR.

need further assistance, please contact the Customer Service

Centre: sales@iec.ch.

IEC 60076-10-1 ®

Edition 2.1 2020-11

CONSOLIDATED VERSION

INTERNATIONAL

STANDARD

colour

inside

Power transformers –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

INTERNATIONAL

ELECTROTECHNICAL

COMMISSION

ICS 29.180 ISBN 978-2-8322-9027-9

IEC 60076-10-1 ®

Edition 2.1 2020-11

CONSOLIDATED VERSION

REDLINE VERSION

colour

inside

Power transformers –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

– 2 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV

IEC 2020

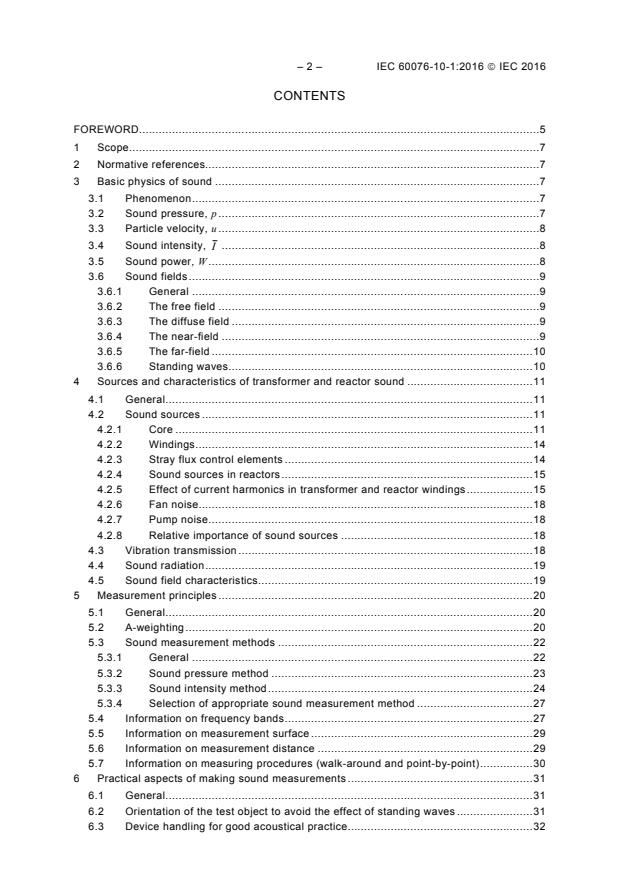

CONTENTS

FOREWORD . 5

1 Scope . 7

2 Normative references . 7

3 Basic physics of sound . 7

3.1 Phenomenon . 7

3.2 Sound pressure, p . 7

3.3 Particle velocity, u . 8

3.4 Sound intensity, . 8

I

3.5 Sound power, W . 8

3.6 Sound fields . 9

3.6.1 General . 9

3.6.2 The free field . 9

3.6.3 The diffuse field . 9

3.6.4 The near-field . 9

3.6.5 The far-field . 10

3.6.6 Standing waves . 10

4 Sources and characteristics of transformer and reactor sound . 11

4.1 General . 11

4.2 Sound sources . 11

4.2.1 Core . 11

4.2.2 Windings . 14

4.2.3 Stray flux control elements . 14

4.2.4 Sound sources in reactors . 15

4.2.5 Effect of current harmonics in transformer and reactor windings . 15

4.2.6 Fan noise . 18

4.2.7 Pump noise . 18

4.2.8 Relative importance of sound sources . 18

4.3 Vibration transmission . 18

4.4 Sound radiation. 19

4.5 Sound field characteristics . 19

5 Measurement principles . 20

5.1 General . 20

5.2 A-weighting . 20

5.3 Sound measurement methods . 22

5.3.1 General . 22

5.3.2 Sound pressure method . 23

5.3.3 Sound intensity method . 24

5.3.4 Selection of appropriate sound measurement method . 27

5.4 Information on frequency bands . 27

5.5 Information on measurement surface . 29

5.6 Information on measurement distance . 29

5.7 Information on measuring procedures (walk-around and point-by-point) . 30

6 Practical aspects of making sound measurements . 31

6.1 General . 31

6.2 Orientation of the test object to avoid the effect of standing waves . 31

6.3 Device handling for good acoustical practice . 32

IEC 2020

6.4 Choice of microphone spacer for the sound intensity method . 33

6.5 Measurements with tank mounted sound panels providing incomplete

coverage . 33

6.6 Testing of reactors . 34

7 Difference between factory tests and field sound level measurements . 34

7.1 General . 34

7.2 Operating voltage . 34

7.3 Load current . 34

7.4 Load power factor and power flow direction . 35

7.5 Operating temperature . 35

7.6 Harmonics in the load current and in voltage . 35

7.7 DC magnetization . 36

7.8 Effect of remanent flux . 36

7.9 Sound level build-up due to reflections . 36

7.10 Converter transformers with saturable reactors (transductors) . 37

Annex A (informative) Sound level built up due to harmonic currents in windings . 38

A.1 Theoretical derivation of winding forces due to harmonic currents . 38

A.2 Force components for a typical current spectrum caused by a B6 bridge. 39

A.3 Estimation of sound level increase due to harmonic currents by calculation . 42

Bibliography . 44

Figure 1 – Simulation of the spatially averaged sound intensity level (solid lines) and

sound pressure level (dashed lines) versus measurement distance d in the near-field . 10

Figure 2 – Example curves showing relative change in lamination length for one type

of electrical core steel during complete cycles of applied 50 Hz a.c. induction up to

peak flux densities B in the range of 1,2 T to 1,9 T . 11

max

Figure 3 – Induction (smooth line) and relative change in lamination length (dotted line)

as a function of time due to applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T – no d.c. bias . 12

Figure 4 – Example curve showing relative change in lamination length during one

complete cycle of applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T with a small d.c. bias of 0,1 T . 12

Figure 5 – Induction (smooth line) and relative change in lamination length (dotted line)

as a function of time due to applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T with a small d.c. bias

of 0,1 T . 13

Figure 6 – Sound level increase due to d.c. current in windings . 13

Figure 7 – Typical sound spectrum due to load current . 14

Figure 8 – Simulation of a sound pressure field (coloured) of a 31,5 MVA transformer

at 100 Hz with corresponding sound intensity vectors along the measurement path . 20

Figure 9 – A-weighting graph derived from function A(f) . 21

Figure 10 – Distribution of disturbances to sound pressure in the test environment . 24

Figure 11 – Microphone arrangement . 25

Figure 12 – Illustration of background sound passing through test area and sound

radiated from the test object . 26

Figure 13 – 1/1- and 1/3-octave bands with transformer tones for 50 Hz and 60 Hz

systems . 28

Figure 14 – Logging measurement demonstrating spatial variation along the

measurement path . 31

Figure 15 – Test environment . 32

Figure A.1 – Current wave shape for a star and a delta connected winding for the

current spectrum given in Table A.2 . 40

– 4 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV

IEC 2020

Table 1 – A-weighting values for the first fifteen transformer tones . 22

Table A.1 – Force components of windings due to harmonic currents . 39

Table A.2 – Current spectrum of a B6 converter bridge . 39

Table A.3 – Calculation of force components and test currents . 41

Table A.4 – Summary of harmonic forces and test currents . 42

IEC 2020

INTERNATIONAL ELECTROTECHNICAL COMMISSION

____________

POWER TRANSFORMERS –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

FOREWORD

1) The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is a worldwide organization for standardization comprising

all national electrotechnical committees (IEC National Committees). The object of IEC is to promote

international co-operation on all questions concerning standardization in the electrical and electronic fields. To

this end and in addition to other activities, IEC publishes International Standards, Technical Specifications,

Technical Reports, Publicly Available Specifications (PAS) and Guides (hereafter referred to as “IEC

Publication(s)”). Their preparation is entrusted to technical committees; any IEC National Committee interested

in the subject dealt with may participate in this preparatory work. International, governmental and non-

governmental organizations liaising with the IEC also participate in this preparation. IEC collaborates closely

with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in accordance with conditions determined by

agreement between the two organizations.

2) The formal decisions or agreements of IEC on technical matters express, as nearly as possible, an international

consensus of opinion on the relevant subjects since each technical committee has representation from all

interested IEC National Committees.

3) IEC Publications have the form of recommendations for international use and are accepted by IEC National

Committees in that sense. While all reasonable efforts are made to ensure that the technical content of IEC

Publications is accurate, IEC cannot be held responsible for the way in which they are used or for any

misinterpretation by any end user.

4) In order to promote international uniformity, IEC National Committees undertake to apply IEC Publications

transparently to the maximum extent possible in their national and regional publications. Any divergence

between any IEC Publication and the corresponding national or regional publication shall be clearly indicated in

the latter.

5) IEC itself does not provide any attestation of conformity. Independent certification bodies provide conformity

assessment services and, in some areas, access to IEC marks of conformity. IEC is not responsible for any

services carried out by independent certification bodies.

6) All users should ensure that they have the latest edition of this publication.

7) No liability shall attach to IEC or its directors, employees, servants or agents including individual experts and

members of its technical committees and IEC National Committees for any personal injury, property damage or

other damage of any nature whatsoever, whether direct or indirect, or for costs (including legal fees) and

expenses arising out of the publication, use of, or reliance upon, this IEC Publication or any other IEC

Publications.

8) Attention is drawn to the Normative references cited in this publication. Use of the referenced publications is

indispensable for the correct application of this publication.

9) Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this IEC Publication may be the subject of

patent rights. IEC shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

This consolidated version of the official IEC Standard and its amendment has been

prepared for user convenience.

IEC 60076-10-1 edition 2.1 contains the second edition (2016-03) [documents

14/847/FDIS and 14/850/RVD] and its amendment 1 (2020-11) [documents 14/1037/CDV

and 14/1047/RVC].

In this Redline version, a vertical line in the margin shows where the technical content

is modified by amendment 1. Additions are in green text, deletions are in strikethrough

red text. A separate Final version with all changes accepted is available in this

publication.

– 6 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV

IEC 2020

International Standard IEC 60076-10-1 has been prepared by technical committee 14: Power

transformers.

This second edition constitutes a technical revision.

This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous

edition:

a) extended information on sound fields provided;

b) effect of current harmonics in windings enfolded;

c) updated information on measuring methods sound pressure and sound intensity given;

d) supporting information on measuring procedures walk-around and point-by-point given;

e) clarification of A-weighting provided;

f) new information on frequency bands given;

g) background information on measurement distance provided;

h) new annex on sound-built up due to harmonic currents in windings introduced.

This standard is to be read in conjunction with IEC 60076-10.

This publication has been drafted in accordance with the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

A list of all parts in the IEC 60076 series, published under the general title Power

transformers, can be found on the IEC website.

The committee has decided that the contents of the base publication and its amendment will

remain unchanged until the stability date indicated on the IEC web site under

"http://webstore.iec.ch" in the data related to the specific publication. At this date, the

publication will be

• reconfirmed,

• withdrawn,

• replaced by a revised edition, or

• amended.

IMPORTANT – The 'colour inside' logo on the cover page of this publication indicates

that it contains colours which are considered to be useful for the correct

understanding of its contents. Users should therefore print this document using a

colour printer.

IEC 2020

POWER TRANSFORMERS –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

1 Scope

This part of IEC 60076 provides supporting information to help both manufacturers and

purchasers to apply the measurement techniques described in IEC 60076-10. Besides the

introduction of some basic acoustics, the sources and characteristics of transformer and

reactor sound are described. Practical guidance on making measurements is given, and

factors influencing the accuracy of the methods are discussed. This application guide also

indicates why values measured in the factory may differ from those measured in service.

This application guide is applicable to transformers and reactors together with their

associated cooling auxiliaries.

2 Normative references

The following documents, in whole or in part, are normatively referenced in this document and

are indispensable for its application. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For

undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any

amendments) applies.

IEC 60076-10:2016, Power transformers – Part 10: Determination of sound levels

3 Basic physics of sound

3.1 Phenomenon

Sound is a wave of pressure variation (in air, water or other elastic media) that the human ear

can detect. Pressure variations travel through the medium (for the purposes of this document,

air) from the sound source to the listener’s ears.

The number of cyclic pressure variations per second is called the ‘frequency’ of the sound

measured in hertz, Hz. A specific frequency of sound is perceived as a distinctive tone or

pitch. Transformer ‘hum’ is low in frequency, typically with fundamental frequencies of 100 Hz

or 120 Hz, while a whistle is of higher frequency, typically above 3 kHz. The normal frequency

range of hearing for a healthy young person extends from approximately 20 Hz to 20 kHz.

3.2 Sound pressure, p

The root-mean-square (r.m.s.) of instantaneous sound pressures over a given time interval at

a specific location is called the sound pressure. It is measured in pascal, Pa.

Sound pressure is a scalar quantity, meaning that it is characterised by magnitude only.

The lowest sound pressure that a healthy human ear can detect is strongly dependent on

frequency; at 1 kHz it has a magnitude of 20 µPa. The threshold of pain corresponds to a

sound pressure of more than a million times higher, 20 Pa. Because of this large range, to

avoid the use of large numbers, the decibel scale (dB) is used in acoustics. The reference

level for sound pressure for the logarithmic scale is 20 µPa corresponding to 0 dB and the

20 Pa threshold of pain corresponds to 120 dB.

– 8 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV

IEC 2020

An additional and very useful aspect of the decibel scale is that it gives a better approximation

to the human perception of loudness than the linear pascal scale as the ear responds to

sound logarithmically.

In the field of acoustics it is generally accepted that

• 1 dB change in level is imperceptible;

• 3 dB change in level is perceptible;

• 10 dB change in level is perceived to be twice as loud.

Human hearing is frequency dependent. The sensitivity peaks at about 1 kHz and reduces at

lower and higher frequencies. An internationally standardized filter termed ‘A-weighting’

ensures that sound measurements reflect the human perception of sound over the whole

frequency range of hearing (see 5.2).

3.3 Particle velocity, u

The root-mean-square (r.m.s.) of instantaneous particle velocity over a given time interval at a

specific location is called particle velocity. It is measured in metres per second, m/s.

This quantity describes the oscillation velocity of the particles of the medium in which the

sound waves are propagating. It is characterised by magnitude and direction and is therefore

a vector quantity.

3.4 Sound intensity,

I

The time-averaged product of the instantaneous sound pressure and instantaneous particle

velocity at a specific location is called sound intensity:

(1)

I = (p(t)×u (t))dt

∫

T

T

It is measured in watts per square metre, W/m .

Sound intensity describes the sound power flow per unit area and is a vector quantity with

magnitude and direction. The normal sound intensity is the sound power flow per unit area

measured in a direction normal, i.e. at 90º to the specified unit area.

The direction of the sound power flow is determined by the phase angle of the particle velocity

at the specific location.

3.5 Sound power, W

Sound power is the rate of acoustic energy radiated from a sound source. It is stated in watts.

A sound source radiates power into the surrounding air resulting in a sound field. Sound

power characterises the emission of the sound source. Sound pressure and particle velocity

characterise the sound at a specific location. The sound pressure which is heard or measured

with a microphone is dependent on the distance from the source and the properties of the

acoustic environment. Therefore, the sound power of a source cannot be quantified by simply

measuring sound pressure or intensity alone. The determination of sound power requires an

integration of sound pressure or sound intensity over the entire enveloping surface. Sound

power is more or less independent of the environment and is therefore a unique descriptor of

the sound source.

IEC 2020

3.6 Sound fields

3.6.1 General

A sound field is a region through which sound waves propagate. It is classified according to

the manner in which the sound waves propagate.

When sound pressure and particle velocity are in phase, the corresponding sound field is said

to be active. When sound pressure and particle velocity are 90° out of phase, the

corresponding sound field is said to be reactive. With an active field the sound energy

propagates entirely outwards from the source, as it does (approximately) in far-fields (see

3.6.5). In case of a reactive field the sound energy is travelling outwards but it will be returned

at a later instant; the energy is stored as if in a spring. Examples for reactive fields are the

diffuse field of a reverberant room (see 3.6.3) and standing waves (see 3.6.6). Averaged over

a cycle, the net energy transfer in a reactive field is zero and hence the measured sound

intensity is zero, although sound pressure and particle velocity are present.

A practical sound field is composed of both active and reactive components.

3.6.2 The free field

A sound field in a homogeneous isotropic medium whose boundaries exert a negligible effect

on sound waves is called a free field. It is an idealised free space where there are no

disturbances and through which active sound power propagates.

These conditions hold in the open air when sufficiently far away from the ground and any

walls, or in a fully anechoic chamber where all the sound striking the walls, ceiling and floor is

absorbed.

Sound propagation from a theoretical point source within a free field environment is

characterised by a 6 dB drop in sound pressure level and intensity level each time the

distance from the source is doubled. This is also approximately correct when the distance

from an area source is large enough for it to appear as a theoretical point source.

When measuring power transformer sound levels free field conditions will be approached with

the exception of reflections from the floor.

IEC 60076-10 requires all sound measurements to be made over a reflecting surface.

Therefore, measurements in fully anechoic chambers are not allowed.

3.6.3 The diffuse field

In a diffuse field, multiple reflections result in a sound field with equal probability of direction

and magnitude, hence the same sound pressure level exists at all locations and the sound

intensity tends to zero. This field is approximated in a reverberant room. According to the law

of conservation of energy, an equilibrium condition will occur when the sound power absorbed

by or transmitted through the room boundaries equals the sound power emitted by the source.

This phenomenon may result in very high sound pressure levels in environments having low

sound absorption or transmission characteristics.

A practical example of a diffuse field may be the interior of a transformer sound enclosure.

3.6.4 The near-field

The acoustic near-field is considered to be the region adjacent to the vibrating surface of the

sound source, usually defined as being within a distance of ¼ of the wavelength of the

particular frequency of interest. This region is characterized by the existence of both active

and reactive sound components. The reactive sound component decays exponentially with

distance from the vibrating surface of the sound source.

– 10 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV

IEC 2020

Reactive sound components are created if the bending wavelength of the vibrating structure is

shorter than the wavelength of the radiated sound. Sound radiation at this condition is

characterised by acoustic short-circuits between adjacent regions with over-pressure and

under-pressure. In such acoustic short-circuits the air acts as a mass-spring system storing

and releasing energy in every cycle. As a result, a part of the sound power is always being

circulated and not all of it is radiated into the far-field (see 3.6.5).

The extent of the near-field reduces with increasing frequency.

Sound pressure measurements applied in the near-field will result in a systematic

overestimation (Figure 1) because of the inherent phase difference between the sound

pressure and particle velocity in the near-field (see 3.6.1). As a result, spatially averaged

sound pressure levels are typically 2 dB to 5 dB higher whilst spot measurements may be up

to 15 dB higher than the corresponding measured sound intensity level.

100 Hz

75 200 Hz

300 Hz

0 0,1 0,2 0,3 0,4 0,5 0,6 0,7 0,8 0,9 1

d (m)

IEC

Figure 1 – Simulation of the spatially averaged sound intensity level (solid lines) and

sound pressure level (dashed lines) versus measurement distance d in the near-field

3.6.5 The far-field

The sound field beyond a certain distance from the source where inherent disturbances due to

the size and shape of the source as well as other interfering disturbances become

insignificant is called the far-field. In this field the source can be treated as a theoretical point

source and approximate free field conditions exist.

3.6.6 Standing waves

Standing waves are the result of interference between two sound waves of the same

frequency travelling in opposite directions. Standing waves are formed as a result of

reflections between a sound source and structural discontinuities such as the boundaries of

the sound field, emphasised if the reflecting surfaces are parallel and when the relationship

between sound frequency and distance meets certain conditions. The existence of standing

waves of frequency f depends upon the distance d between the reflecting walls as follows:

ν

c

(2)

f = ν

ν

2 d

where c is the speed of sound in air in m/s (at 20 °C, c = 343 m/s), ν = 1,2,3….

A standing wave does not transmit energy to the far-field; it is an example of a reactive field.

L (dB)(A)

IEC 2020

Within the region of a standing wave

• large variations in measured sound pressure will occur over small distances with the

tendency to overestimate sound pressure;

• sound intensity measurements tend to be inaccurate and underestimate the actual sound

intensity.

4 Sources and characteristics of transformer and reactor sound

4.1 General

Transformer and reactor sound has several inherent physical origins. The significance of

those origins of sound generation depends on the design of the equipment and its operating

conditions. The design will impact the sound producing vibrations and their propagation from

the origin to the transformer tank or enclosure surface and finally the sound radiation into the

air.

4.2 Sound sources

4.2.1 Core

Magnetostriction is the change in dimension observed in ferromagnetic materials when they

are subjected to a change in magnetic flux density (induction). In electrical core steel this

dimensional change is in the range of 0,1 µm to 10 µm per metre length (µm/m) at typical

induction levels. Figure 2 shows magnetostriction versus flux density for one type of core

lamination measured at five different flux densities. Each loop describes one 50 Hz cycle with

flux density B .

max

B = 1,9 T

max

B = 1,8 T

max

B = 1,6 T

max

B = 1,4 T

max

B = 1,2 T

max

–1

–2

–3

–2 –1 0 1 2

Flux density T

IEC

Figure 2 – Example curves showing relative change in lamination length for one type

of electrical core steel during complete cycles of applied 50 Hz a.c. induction

up to peak flux densities B in the range of 1,2 T to 1,9 T

max

NOTE 1 Mechanical stresses in core laminations will have a strong influence on magnetostriction.

The strain does not depend on the sign of the flux density, only on its magnitude and

orientation relative to certain crystallographic axes of the material. Therefore, when excited by

a sinusoidal flux, the fundamental frequency of the dimensional change will be twice the

exciting frequency. The effect is highly non-linear, especially at induction levels near

saturation. This non-linearity will result in a significant harmonic content of the strain and this

causes the vibration spectrum of the core. Figure 3 shows the magnetostriction for a

= 1,8 T and a frequency of 50 Hz. It has a periodicity of double

sinusoidal induction with B

max

the exciting frequency with peaks at 5 ms and 15 ms which are indistinguishable.

Strain (µ m/m)

– 12 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV

IEC 2020

The sound emitted by transformer cores depends on the velocity of the vibrations, i.e. the rate

of change of the magnetostriction (dotted line in Figure 3). This results in an amplification of

the harmonics (distortion) in relation to the fundamental which is at double the exciting

frequency. Several even multiples of the exciting frequency will be seen in the spectrum; in

such cases the fundamental component at double the exciting frequency is seldom the

dominant frequency component of the A-weighted sound.

3 3

2 2

1 1

0 0

–1 –1

–2 –2

–3 –3

0 10 20 30 40

Time (ms)

IEC

Figure 3 – Induction (smooth line) and relative change in lamination length (dotted line)

as a function of time due to applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T – no d.c. bias

If the flux has a d.c. bias, for example due to remanence in the core from preceding testing of

the windings’ resistance, or due to a d.c. component in the current, the strong non-linearity of

magnetostriction causes a significant increase in vibration amplitudes. With a d.c. bias on the

induction, the peaks in magnetostriction at the positive and negative peak flux density differ

significantly; obvious in the magnetostriction loop in Figure 4.

–1

–2

–3

–2 –1 0 1 2

Flux density (T)

IEC

Figure 4 – Example curve showing relative change in lamination length

during one complete cycle of applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T

with a small d.c. bias of 0,1 T

The vibration pattern is now repeated every cycle, that is every 20 ms in a 50 Hz system,

indicating a magnetostriction at exciting frequency (see Figure 5). The presence of odd

harmonics in the sound spectrum is a clear indication of d.c. bias in the induction.

Flux density (T)

Strain (µ m/m)

Strain (µ m/m)

IEC 2020

2 2

0 0

–1 –1

–2 –2

–3

–3

0 10 20 30 40

Time (ms)

IEC

Figure 5 – Induction (smooth line) and relative change in lamination length (dotted line)

as a function of time due to applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T

with a small d.c. bias of 0,1 T

A d.c. bias in magnetization can significantly affect the sound level of a transformer.

Therefore, a transformer undergoing sound tests shall be energised until the temporary

effects of inrush currents and remanence have decayed and the sound levels have stabilised.

The ratio between the d.c. bias current and the r.m.s. no-load current is a useful parameter

for predicting the increase in sound power due to the d.c. bias current. The relationship

between d.c. bias current over no-load current and sound level increase has been measured

on a number of large power transformers; Figure 6 shows one set of this data.

Y

B = 1,6 T

max

B = 1,7 T

max

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

X

IEC

Key

X axis d.c. bias current as per unit of a.c. no-load current (r.m.s.)

Y axis increase in total sound level in dB(A)

Figure 6 – Sound level increase due to d.c. current in windings

NOTE 2 Figure 6 shows the results for a certain design of large power transformers with a core having a path for

flux return and the core made from high permeable electrical steel. For other constructions, for example with

different core form or different electrical steel type, the curve can deviate in detail but will contain the same upward

trend.

Flux density (T)

Strain (µ m/m)

– 14 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV

IEC 2020

4.2.2 Windings

Load currents in transformer and reactor windings generate a magnetic field that oscillates at

the excitation frequency. The resultant electromagnetic forces on the windings act both axially

and radially. The magnitude of these forces depends on the magnitude of the load current and

on the magnetic field, which itself is a function of the load current. Thus, the magnetic forces

on the windings are proportional to the square of the load current while their frequency is

twice the excitation frequency. The resulting vibration amplitudes depend on the elastic

properties of the conductor, those of the electrical insulation and the proximity of the

mechanical eigenfrequencies (natural frequencies of the windings) to the vibration frequency.

In a well clamped and tightly wound winding, the elastic properties of the insulating material

are almost linear in the range of displacements occurring under normal operating currents.

Metals have very linear elastic moduli. Therefore harmonic vibration is normally minimal and

the fundamental frequency (double the exciting frequency) dominates the vibration spectrum

of windings (see Figure 7).

Winding deflections and their vibrational velocities are proportional to the excitation force

which is proportional to the square of the load current. The sound power radiated from a

vibrating body is proportional to the square of the vibration velocity (see 4.4). Consequently,

the sound power generated by windings varies with the fourth power of the load current.

Harmonics in the load current appear in the sound spectrum at twice their electrical frequency

and at the sum and difference of all their frequencies. They can contribute significantly to the

transformer or reactor sound level. For more details see 4.2.5.

0 200 400 600 800 1 000 1 200 1 400 1 600 1 800 2 000

Frequency (Hz)

IEC

Figure 7 – Typical sound spectrum due to load current

4.2.3 Stray flux control elements

Magnetic stray flux in loaded transformers is linked to windings and connection leads. This

stray flux shall be controlled to avoid the overheating of inactive metal parts such as the tank

by reducing eddy current losses. There are in principle three possibilities to control magnetic

stray flux:

• by application of laminated electrical steel the stray flux is guided in a controlled way.

Elements providing this guidance are commonly called ‘shunts’ or ‘tank shunts’;

A-weigthed sound pressure level (dB)(A)

IEC 2020

• by application of copper or aluminium shields the stray flux is repelled by eddy current

loops in the shield;

• by sizing the tank such that stray flux control is not necessary.

Elements used for stray flux control as well as the tank itself are also sources of vibration due

to electromagnetic forces and magnetostriction and they impact the overall sound power level.

The method of attachment of stray flux control elements may influence the sound power level.

4.2.4 Sound sources in reactors

There are several types of single-phase and three-phase reactors, generally utilising two

different technologies in their design.

• In air-core reactors, the sound power produced by the winding due to the load current is

dominant. The interaction of the current flowing through the winding and its magnetic field

lead to vibrational winding forces. While the oscillating forces can be clearly determined,

the vibrational response of the winding structure is complex. The vibrational amplitude, the

size of the sound radiating surface and its radiation efficiency determine the sound power.

The sound power is governed by the magnitude of the winding vibration in the radial

direction (because the winding represents the main part of the radiating surface). The

contribution of axial winding vibrations and that of other components to the total sound

power is usually low.

• In magnetically-shielded reactors (with or without gapped cores), the magnetic force

between the yokes tends to close the gap as the flux increases; the cyclic displacement

thus produced is the dominant sound source. This force mechanically excites the entire

magnetic circuit of the reactor, resulting in a sound spectrum dominated by double the

excitation frequency and its first few harmonics. Magnetostriction, winding vibrations and

stray flux control elements are also contributing factors to sound power radiation.

NOTE See IEC 60076-6 for definitions of different types of reactor.

4.2.5 Effect of current harmonics in transformer and reactor windings

4.2.5.1 General

As indicated in 7.6 of this standard, power electronic devices can be a source of current

harmonics. This effect on the overall sound power level can be significant.

The spectrum of harmonic currents in magnitude and phase shall be specified by the

purchaser or the manufacturer of the power electronic device in order to predict a realistic in

service sound power level. Where phase angles are not available a statistical approach may

be applied.

More detailed information of the theory and engineering practice of additional sound produced

by harmonic currents in windings is given in Annex A of this standard.

Radiated sound power from a transformer/reactor depends on the current at all frequencies

but usually it is only the fundamental and the most significant harmonic currents out of the

current spectrum that contribute significantly.

The determination of the additional sound power due to harmonic currents can be performed

with two different approaches:

• by exciting and measuring individual frequencies (usually applicable only for special

reactors, such as filter reactors);

• by calculation of the individual frequency contributions.

– 16 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016+AMD1:2020 CSV

...

IEC 60076-10-1 ®

Edition 2.0 2016-03

INTERNATIONAL

STANDARD

NORME

INTERNATIONALE

colour

inside

Power transformers –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

Transformateurs de puissance –

Partie 10-1: Détermination des niveaux de bruit – Guide d'application

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from

either IEC or IEC's member National Committee in the country of the requester. If you have any questions about IEC

copyright or have an enquiry about obtaining additional rights to this publication, please contact the address below or

your local IEC member National Committee for further information.

Droits de reproduction réservés. Sauf indication contraire, aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite

ni utilisée sous quelque forme que ce soit et par aucun procédé, électronique ou mécanique, y compris la photocopie

et les microfilms, sans l'accord écrit de l'IEC ou du Comité national de l'IEC du pays du demandeur. Si vous avez des

questions sur le copyright de l'IEC ou si vous désirez obtenir des droits supplémentaires sur cette publication, utilisez

les coordonnées ci-après ou contactez le Comité national de l'IEC de votre pays de résidence.

IEC Central Office Tel.: +41 22 919 02 11

3, rue de Varembé Fax: +41 22 919 03 00

CH-1211 Geneva 20 info@iec.ch

Switzerland www.iec.ch

About the IEC

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is the leading global organization that prepares and publishes

International Standards for all electrical, electronic and related technologies.

About IEC publications

The technical content of IEC publications is kept under constant review by the IEC. Please make sure that you have the

latest edition, a corrigenda or an amendment might have been published.

IEC Catalogue - webstore.iec.ch/catalogue Electropedia - www.electropedia.org

The stand-alone application for consulting the entire The world's leading online dictionary of electronic and

bibliographical information on IEC International Standards, electrical terms containing 20 000 terms and definitions in

Technical Specifications, Technical Reports and other English and French, with equivalent terms in 15 additional

documents. Available for PC, Mac OS, Android Tablets and languages. Also known as the International Electrotechnical

iPad. Vocabulary (IEV) online.

IEC publications search - www.iec.ch/searchpub IEC Glossary - std.iec.ch/glossary

The advanced search enables to find IEC publications by a 65 000 electrotechnical terminology entries in English and

variety of criteria (reference number, text, technical French extracted from the Terms and Definitions clause of

committee,…). It also gives information on projects, replaced IEC publications issued since 2002. Some entries have been

and withdrawn publications. collected from earlier publications of IEC TC 37, 77, 86 and

CISPR.

IEC Just Published - webstore.iec.ch/justpublished

Stay up to date on all new IEC publications. Just Published IEC Customer Service Centre - webstore.iec.ch/csc

details all new publications released. Available online and If you wish to give us your feedback on this publication or

also once a month by email. need further assistance, please contact the Customer Service

Centre: csc@iec.ch.

A propos de l'IEC

La Commission Electrotechnique Internationale (IEC) est la première organisation mondiale qui élabore et publie des

Normes internationales pour tout ce qui a trait à l'électricité, à l'électronique et aux technologies apparentées.

A propos des publications IEC

Le contenu technique des publications IEC est constamment revu. Veuillez vous assurer que vous possédez l’édition la

plus récente, un corrigendum ou amendement peut avoir été publié.

Catalogue IEC - webstore.iec.ch/catalogue Electropedia - www.electropedia.org

Application autonome pour consulter tous les renseignements

Le premier dictionnaire en ligne de termes électroniques et

bibliographiques sur les Normes internationales,

électriques. Il contient 20 000 termes et définitions en anglais

Spécifications techniques, Rapports techniques et autres

et en français, ainsi que les termes équivalents dans 15

documents de l'IEC. Disponible pour PC, Mac OS, tablettes

langues additionnelles. Egalement appelé Vocabulaire

Android et iPad.

Electrotechnique International (IEV) en ligne.

Recherche de publications IEC - www.iec.ch/searchpub

Glossaire IEC - std.iec.ch/glossary

La recherche avancée permet de trouver des publications IEC 65 000 entrées terminologiques électrotechniques, en anglais

en utilisant différents critères (numéro de référence, texte, et en français, extraites des articles Termes et Définitions des

comité d’études,…). Elle donne aussi des informations sur les publications IEC parues depuis 2002. Plus certaines entrées

projets et les publications remplacées ou retirées. antérieures extraites des publications des CE 37, 77, 86 et

CISPR de l'IEC.

IEC Just Published - webstore.iec.ch/justpublished

Service Clients - webstore.iec.ch/csc

Restez informé sur les nouvelles publications IEC. Just

Published détaille les nouvelles publications parues. Si vous désirez nous donner des commentaires sur cette

Disponible en ligne et aussi une fois par mois par email. publication ou si vous avez des questions contactez-nous:

csc@iec.ch.

IEC 60076-10-1 ®

Edition 2.0 2016-03

INTERNATIONAL

STANDARD

NORME

INTERNATIONALE

colour

inside

Power transformers –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

Transformateurs de puissance –

Partie 10-1: Détermination des niveaux de bruit – Guide d'application

INTERNATIONAL

ELECTROTECHNICAL

COMMISSION

COMMISSION

ELECTROTECHNIQUE

INTERNATIONALE

ICS 29.180 ISBN 978-2-8322-3253-8

– 2 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016 IEC 2016

CONTENTS

FOREWORD . 5

1 Scope . 7

2 Normative references. 7

3 Basic physics of sound . 7

3.1 Phenomenon . 7

3.2 Sound pressure, p . 7

3.3 Particle velocity, u . 8

3.4 Sound intensity, I . 8

3.5 Sound power, W . 8

3.6 Sound fields . 9

3.6.1 General . 9

3.6.2 The free field . 9

3.6.3 The diffuse field . 9

3.6.4 The near-field . 9

3.6.5 The far-field . 10

3.6.6 Standing waves . 10

4 Sources and characteristics of transformer and reactor sound . 11

4.1 General . 11

4.2 Sound sources . 11

4.2.1 Core . 11

4.2.2 Windings . 14

4.2.3 Stray flux control elements . 14

4.2.4 Sound sources in reactors . 15

4.2.5 Effect of current harmonics in transformer and reactor windings . 15

4.2.6 Fan noise . 18

4.2.7 Pump noise . 18

4.2.8 Relative importance of sound sources . 18

4.3 Vibration transmission . 18

4.4 Sound radiation . 19

4.5 Sound field characteristics . 19

5 Measurement principles . 20

5.1 General . 20

5.2 A-weighting . 20

5.3 Sound measurement methods . 22

5.3.1 General . 22

5.3.2 Sound pressure method . 23

5.3.3 Sound intensity method . 24

5.3.4 Selection of appropriate sound measurement method . 27

5.4 Information on frequency bands . 27

5.5 Information on measurement surface . 29

5.6 Information on measurement distance . 29

5.7 Information on measuring procedures (walk-around and point-by-point) . 30

6 Practical aspects of making sound measurements . 31

6.1 General . 31

6.2 Orientation of the test object to avoid the effect of standing waves . 31

6.3 Device handling for good acoustical practice . 32

6.4 Choice of microphone spacer for the sound intensity method . 33

6.5 Measurements with tank mounted sound panels providing incomplete

coverage . 33

6.6 Testing of reactors . 34

7 Difference between factory tests and field sound level measurements . 34

7.1 General . 34

7.2 Operating voltage . 34

7.3 Load current . 34

7.4 Load power factor and power flow direction . 35

7.5 Operating temperature . 35

7.6 Harmonics in the load current and in voltage . 35

7.7 DC magnetization . 36

7.8 Effect of remanent flux . 36

7.9 Sound level build-up due to reflections . 36

7.10 Converter transformers with saturable reactors (transductors) . 37

Annex A (informative) Sound level built up due to harmonic currents in windings . 38

A.1 Theoretical derivation of winding forces due to harmonic currents . 38

A.2 Force components for a typical current spectrum caused by a B6 bridge . 39

A.3 Estimation of sound level increase due to harmonic currents by calculation . 42

Bibliography . 44

Figure 1 – Simulation of the spatially averaged sound intensity level (solid lines) and

sound pressure level (dashed lines) versus measurement distance d in the near-field . 10

Figure 2 – Example curves showing relative change in lamination length for one type

of electrical core steel during complete cycles of applied 50 Hz a.c. induction up to

peak flux densities B in the range of 1,2 T to 1,9 T . 11

max

Figure 3 – Induction (smooth line) and relative change in lamination length (dotted line)

as a function of time due to applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T – no d.c. bias . 12

Figure 4 – Example curve showing relative change in lamination length during one

complete cycle of applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T with a small d.c. bias of 0,1 T . 12

Figure 5 – Induction (smooth line) and relative change in lamination length (dotted line)

as a function of time due to applied 50 Hz a.c. induction at 1,8 T with a small d.c. bias

of 0,1 T . 13

Figure 6 – Sound level increase due to d.c. current in windings . 13

Figure 7 – Typical sound spectrum due to load current . 14

Figure 8 – Simulation of a sound pressure field (coloured) of a 31,5 MVA transformer

at 100 Hz with corresponding sound intensity vectors along the measurement path . 20

Figure 9 – A-weighting graph derived from function A(f) . 21

Figure 10 – Distribution of disturbances to sound pressure in the test environment . 24

Figure 11 – Microphone arrangement . 25

Figure 12 – Illustration of background sound passing through test area and sound

radiated from the test object . 26

Figure 13 – 1/1- and 1/3-octave bands with transformer tones for 50 Hz and 60 Hz

systems . 28

Figure 14 – Logging measurement demonstrating spatial variation along the

measurement path . 31

Figure 15 – Test environment . 32

Figure A.1 – Current wave shape for a star and a delta connected winding for the

current spectrum given in Table A.2 . 40

– 4 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016 IEC 2016

Table 1 – A-weighting values for the first fifteen transformer tones . 22

Table A.1 – Force components of windings due to harmonic currents . 39

Table A.2 – Current spectrum of a B6 converter bridge . 39

Table A.3 – Calculation of force components and test currents . 41

Table A.4 – Summary of harmonic forces and test currents . 42

INTERNATIONAL ELECTROTECHNICAL COMMISSION

____________

POWER TRANSFORMERS –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

FOREWORD

1) The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is a worldwide organization for standardization comprising

all national electrotechnical committees (IEC National Committees). The object of IEC is to promote

international co-operation on all questions concerning standardization in the electrical and electronic fields. To

this end and in addition to other activities, IEC publishes International Standards, Technical Specifications,

Technical Reports, Publicly Available Specifications (PAS) and Guides (hereafter referred to as “IEC

Publication(s)”). Their preparation is entrusted to technical committees; any IEC National Committee interested

in the subject dealt with may participate in this preparatory work. International, governmental and non-

governmental organizations liaising with the IEC also participate in this preparation. IEC collaborates closely

with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in accordance with conditions determined by

agreement between the two organizations.

2) The formal decisions or agreements of IEC on technical matters express, as nearly as possible, an international

consensus of opinion on the relevant subjects since each technical committee has representation from all

interested IEC National Committees.

3) IEC Publications have the form of recommendations for international use and are accepted by IEC National

Committees in that sense. While all reasonable efforts are made to ensure that the technical content of IEC

Publications is accurate, IEC cannot be held responsible for the way in which they are used or for any

misinterpretation by any end user.

4) In order to promote international uniformity, IEC National Committees undertake to apply IEC Publications

transparently to the maximum extent possible in their national and regional publications. Any divergence

between any IEC Publication and the corresponding national or regional publication shall be clearly indicated in

the latter.

5) IEC itself does not provide any attestation of conformity. Independent certification bodies provide conformity

assessment services and, in some areas, access to IEC marks of conformity. IEC is not responsible for any

services carried out by independent certification bodies.

6) All users should ensure that they have the latest edition of this publication.

7) No liability shall attach to IEC or its directors, employees, servants or agents including individual experts and

members of its technical committees and IEC National Committees for any personal injury, property damage or

other damage of any nature whatsoever, whether direct or indirect, or for costs (including legal fees) and

expenses arising out of the publication, use of, or reliance upon, this IEC Publication or any other IEC

Publications.

8) Attention is drawn to the Normative references cited in this publication. Use of the referenced publications is

indispensable for the correct application of this publication.

9) Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this IEC Publication may be the subject of

patent rights. IEC shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

International Standard IEC 60076-10-1 has been prepared by technical committee 14: Power

transformers.

This second edition cancels and replaces the first edition published in 2005. This edition

constitutes a technical revision.

This edition includes the following significant technical changes with respect to the previous

edition:

a) extended information on sound fields provided;

b) effect of current harmonics in windings enfolded;

c) updated information on measuring methods sound pressure and sound intensity given;

d) supporting information on measuring procedures walk-around and point-by-point given;

e) clarification of A-weighting provided;

f) new information on frequency bands given;

– 6 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016 IEC 2016

g) background information on measurement distance provided;

h) new annex on sound-built up due to harmonic currents in windings introduced.

This standard is to be read in conjunction with IEC 60076-10.

The text of this standard is based on the following documents:

FDIS Report on voting

14/847/FDIS 14/850/RVD

Full information on the voting for the approval of this standard can be found in the report on

voting indicated in the above table.

This publication has been drafted in accordance with the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

A list of all parts in the IEC 60076 series, published under the general title Power

transformers, can be found on the IEC website.

The committee has decided that the contents of this publication will remain unchanged until

the stability date indicated on the IEC website under "http://webstore.iec.ch" in the data

related to the specific publication. At this date, the publication will be

• reconfirmed,

• withdrawn,

• replaced by a revised edition, or

• amended.

IMPORTANT – The 'colour inside' logo on the cover page of this publication indicates

that it contains colours which are considered to be useful for the correct

understanding of its contents. Users should therefore print this document using a

colour printer.

POWER TRANSFORMERS –

Part 10-1: Determination of sound levels – Application guide

1 Scope

This part of IEC 60076 provides supporting information to help both manufacturers and

purchasers to apply the measurement techniques described in IEC 60076-10. Besides the

introduction of some basic acoustics, the sources and characteristics of transformer and

reactor sound are described. Practical guidance on making measurements is given, and

factors influencing the accuracy of the methods are discussed. This application guide also

indicates why values measured in the factory may differ from those measured in service.

This application guide is applicable to transformers and reactors together with their

associated cooling auxiliaries.

2 Normative references

The following documents, in whole or in part, are normatively referenced in this document and

are indispensable for its application. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For

undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any

amendments) applies.

IEC 60076-10:2016, Power transformers – Part 10: Determination of sound levels

3 Basic physics of sound

3.1 Phenomenon

Sound is a wave of pressure variation (in air, water or other elastic media) that the human ear

can detect. Pressure variations travel through the medium (for the purposes of this document,

air) from the sound source to the listener’s ears.

The number of cyclic pressure variations per second is called the ‘frequency’ of the sound

measured in hertz, Hz. A specific frequency of sound is perceived as a distinctive tone or

pitch. Transformer ‘hum’ is low in frequency, typically with fundamental frequencies of 100 Hz

or 120 Hz, while a whistle is of higher frequency, typically above 3 kHz. The normal frequency

range of hearing for a healthy young person extends from approximately 20 Hz to 20 kHz.

3.2 Sound pressure, p

The root-mean-square (r.m.s.) of instantaneous sound pressures over a given time interval at

a specific location is called the sound pressure. It is measured in pascal, Pa.

Sound pressure is a scalar quantity, meaning that it is characterised by magnitude only.

The lowest sound pressure that a healthy human ear can detect is strongly dependent on

frequency; at 1 kHz it has a magnitude of 20 µPa. The threshold of pain corresponds to a

sound pressure of more than a million times higher, 20 Pa. Because of this large range, to

avoid the use of large numbers, the decibel scale (dB) is used in acoustics. The reference

level for sound pressure for the logarithmic scale is 20 µPa corresponding to 0 dB and the

20 Pa threshold of pain corresponds to 120 dB.

– 8 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016 IEC 2016

An additional and very useful aspect of the decibel scale is that it gives a better approximation

to the human perception of loudness than the linear pascal scale as the ear responds to

sound logarithmically.

In the field of acoustics it is generally accepted that

• 1 dB change in level is imperceptible;

• 3 dB change in level is perceptible;

• 10 dB change in level is perceived to be twice as loud.

Human hearing is frequency dependent. The sensitivity peaks at about 1 kHz and reduces at

lower and higher frequencies. An internationally standardized filter termed ‘A-weighting’

ensures that sound measurements reflect the human perception of sound over the whole

frequency range of hearing (see 5.2).

3.3 Particle velocity, u

The root-mean-square (r.m.s.) of instantaneous particle velocity over a given time interval at a

specific location is called particle velocity. It is measured in metres per second, m/s.

This quantity describes the oscillation velocity of the particles of the medium in which the

sound waves are propagating. It is characterised by magnitude and direction and is therefore

a vector quantity.

3.4 Sound intensity,

I

The time-averaged product of the instantaneous sound pressure and instantaneous particle

velocity at a specific location is called sound intensity:

(1)

I = (p(t)×u (t))dt

∫

T

T

It is measured in watts per square metre, W/m .

Sound intensity describes the sound power flow per unit area and is a vector quantity with

magnitude and direction. The normal sound intensity is the sound power flow per unit area

measured in a direction normal, i.e. at 90º to the specified unit area.

The direction of the sound power flow is determined by the phase angle of the particle velocity

at the specific location.

3.5 Sound power, W

Sound power is the rate of acoustic energy radiated from a sound source. It is stated in watts.

A sound source radiates power into the surrounding air resulting in a sound field. Sound

power characterises the emission of the sound source. Sound pressure and particle velocity

characterise the sound at a specific location. The sound pressure which is heard or measured

with a microphone is dependent on the distance from the source and the properties of the

acoustic environment. Therefore, the sound power of a source cannot be quantified by simply

measuring sound pressure or intensity alone. The determination of sound power requires an

integration of sound pressure or sound intensity over the entire enveloping surface. Sound

power is more or less independent of the environment and is therefore a unique descriptor of

the sound source.

3.6 Sound fields

3.6.1 General

A sound field is a region through which sound waves propagate. It is classified according to

the manner in which the sound waves propagate.

When sound pressure and particle velocity are in phase, the corresponding sound field is said

to be active. When sound pressure and particle velocity are 90° out of phase, the

corresponding sound field is said to be reactive. With an active field the sound energy

propagates entirely outwards from the source, as it does (approximately) in far-fields (see

3.6.5). In case of a reactive field the sound energy is travelling outwards but it will be returned

at a later instant; the energy is stored as if in a spring. Examples for reactive fields are the

diffuse field of a reverberant room (see 3.6.3) and standing waves (see 3.6.6). Averaged over

a cycle, the net energy transfer in a reactive field is zero and hence the measured sound

intensity is zero, although sound pressure and particle velocity are present.

A practical sound field is composed of both active and reactive components.

3.6.2 The free field

A sound field in a homogeneous isotropic medium whose boundaries exert a negligible effect

on sound waves is called a free field. It is an idealised free space where there are no

disturbances and through which active sound power propagates.

These conditions hold in the open air when sufficiently far away from the ground and any

walls, or in a fully anechoic chamber where all the sound striking the walls, ceiling and floor is

absorbed.

Sound propagation from a theoretical point source within a free field environment is

characterised by a 6 dB drop in sound pressure level and intensity level each time the

distance from the source is doubled. This is also approximately correct when the distance

from an area source is large enough for it to appear as a theoretical point source.

When measuring power transformer sound levels free field conditions will be approached with

the exception of reflections from the floor.

IEC 60076-10 requires all sound measurements to be made over a reflecting surface.

Therefore, measurements in fully anechoic chambers are not allowed.

3.6.3 The diffuse field

In a diffuse field, multiple reflections result in a sound field with equal probability of direction

and magnitude, hence the same sound pressure level exists at all locations and the sound

intensity tends to zero. This field is approximated in a reverberant room. According to the law

of conservation of energy, an equilibrium condition will occur when the sound power absorbed

by or transmitted through the room boundaries equals the sound power emitted by the source.

This phenomenon may result in very high sound pressure levels in environments having low

sound absorption or transmission characteristics.

A practical example of a diffuse field may be the interior of a transformer sound enclosure.

3.6.4 The near-field

The acoustic near-field is considered to be the region adjacent to the vibrating surface of the

sound source, usually defined as being within a distance of ¼ of the wavelength of the

particular frequency of interest. This region is characterized by the existence of both active

and reactive sound components. The reactive sound component decays exponentially with

distance from the vibrating surface of the sound source.

– 10 – IEC 60076-10-1:2016 IEC 2016

Reactive sound components are created if the bending wavelength of the vibrating structure is

shorter than the wavelength of the radiated sound. Sound radiation at this condition is

characterised by acoustic short-circuits between adjacent regions with over-pressure and

under-pressure. In such acoustic short-circuits the air acts as a mass-spring system storing

and releasing energy in every cycle. As a result, a part of the sound power is always being

circulated and not all of it is radiated into the far-field (see 3.6.5).

The extent of the near-field reduces with increasing frequency.

Sound pressure measurements applied in the near-field will result in a systematic

overestimation (Figure 1) because of the inherent phase difference between the sound

pressure and particle velocity in the near-field (see 3.6.1). As a result, spatially averaged

sound pressure levels are typically 2 dB to 5 dB higher whilst spot measurements may be up

to 15 dB higher than the corresponding measured sound intensity level.

100 Hz

75 200 Hz

300 Hz

0 0,1 0,2 0,3 0,4 0,5 0,6 0,7 0,8 0,9 1

d (m)

IEC

Figure 1 – Simulation of the spatially averaged sound intensity level (solid lines) and

sound pressure level (dashed lines) versus measurement distance d in the near-field

3.6.5 The far-field

The sound field beyond a certain distance from the source where inherent disturbances due to

the size and shape of the source as well as other interfering disturbances become

insignificant is called the far-field. In this field the source can be treated as a theoretical point

source and approximate free field conditions exist.

3.6.6 Standing waves

Standing waves are the result of interference between two sound waves of the same