SIST ISO 18909:2023

(Main)Photography - Processed photographic colour films and paper prints - Methods for measuring image stability

Photography - Processed photographic colour films and paper prints - Methods for measuring image stability

This document describes test methods for determining the long-term dark storage stability of colour photographic images and the colour stability of such images when subjected to certain illuminants at specified temperatures and relative humidities.

This document is applicable to colour photographic images made with traditional, continuous-tone photographic materials with images formed with dyes. These images are generated with chromogenic, silver dye-bleach, dye transfer, and dye-diffusion-transfer instant systems. The tests have not been verified for evaluating the stability of colour images produced with dry- and liquid-toner electrophotography, thermal dye transfer (sometimes called dye sublimation), ink jet, pigment-gelatin systems, offset lithography, gravure and related colour imaging systems. If these reflection print materials, including silver halide (chromogenic), are digitally printed, refer to ISO 18936, ISO 18941, ISO 18946, and ISO 18949 for dark stability tests, and the ISO 18937 series for light stability tests.

This document does not include test procedures for the physical stability of images, supports or binder materials. However, it is recognized that in some instances, physical degradation such as support embrittlement, emulsion cracking or delamination of an image layer from its support, rather than image stability, will determine the useful life of a colour film or print material.

Photographie - Films et papiers photographiques couleur traités - Méthodes de mesure de la stabilité de l'image

Fotografija - Procesirani barvni fotografski filmi in papirni natisi - Metode za merjenje slikovne stabilnosti

Ta dokument opisuje preskusne metode za določanje dolgotrajne stabilnosti barvnih fotografskih slik pri shranjevanju v temi in barvno stabilnost takih slik pri izpostavitvi določenim svetilom pri določenih temperaturah in relativni vlagi.

Ta dokument se uporablja za barvne fotografske slike, narejene s tradicionalnimi fotografskimi materiali z neprekinjenim tonom s slikami, narejenimi z barvili. Te slike nastanejo s kromogenskimi sistemi, sistemi s srebrovim barvilom in belilom, sistemi s prenosom barvil in polaroidnimi sistemi z difuzijo in prenosom barvil. Preskusi niso preverjeni za vrednotenje stabilnosti barvnih slik, narejenih z elektrofotografijo s suhim in tekočim tonerjem, s sistemom s toplotnim prenosom barvil (včasih imenovanim sublimacija barvil), z brizgalnim tiskalnikom, s sistemom pigmentov in želatine, ofsetno litografijo, gravuro in podobnimi sistemi za barvno upodabljanje. Če so ti materiali za odsevni tisk, vključno s srebrovim halogenidom (kromogenski) natisnjeni digitalno, glej standarde ISO 18936, ISO 18941, ISO 18946 in ISO 18949 za preskuse stabilnosti v temi in serijo ISO 18937 za preskuse stabilnosti na svetlobi.

Ta dokument ne vključuje preskusnih postopkov za fizikalno stabilnost slik, podpor ali vezivnih materialov. Priznava pa se, da v nekaterih primerih fizikalna degradacija, kot je krhkost podpore, pokanje emulzije ali delaminacija plasti slike s podpore, bolj kot stabilnost slike določa življenjsko dobo barvnega filma ali materiala za tiskanje.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 20-Aug-2023

- Technical Committee

- GRT - Graphical technology

- Current Stage

- 6060 - National Implementation/Publication (Adopted Project)

- Start Date

- 17-Jun-2023

- Due Date

- 22-Aug-2023

- Completion Date

- 21-Aug-2023

Relations

- Effective Date

- 01-Sep-2023

- Effective Date

- 01-Sep-2023

Overview

SIST ISO 18909:2023 - "Photography - Processed photographic colour films and paper prints - Methods for measuring image stability" - defines standardized test methods to evaluate the long-term dark storage stability and light (display) stability of colour photographic images formed with dyes. It applies to traditional continuous‑tone photographic materials (chromogenic, silver dye‑bleach, dye transfer, dye‑diffusion‑transfer instant systems) and describes accelerated ageing and light‑exposure procedures used to predict real-world performance.

Key topics and technical requirements

- Scope and exclusions

- Covers dye‑based, continuous‑tone colour films and prints.

- Not verified for electrophotography (dry/liquid toner), thermal dye transfer (dye‑sublimation), inkjet, pigment‑gelatin systems, offset/gravure printing.

- For digitally printed reflection materials, refers to related ISO standards (see Related Standards).

- Dark‑stability test methods

- Accelerated high‑temperature ageing with controlled relative humidity to model long‑term dark storage behaviour.

- Specimen handling options: free‑hanging in air or sealed in moisture‑proof bags; conditioning and incubation procedures are specified.

- Data treatment and computation of image‑life parameters (including Arrhenius‑based approaches in informative annexes).

- Light‑stability (display) test methods

- Controlled irradiation tests with specified illuminants, temperatures and relative humidity.

- Illuminant prescriptions include xenon arc for simulated indoor/outdoor daylight (e.g., 50–100 klx), glass‑filtered fluorescent (Cool White, ≤80 klx), incandescent (CIE illuminant A, ~3.0 klx), simulated outdoor sunlight (D65 at 100 klx), and high‑intensity slide projection (1 000 klx).

- Requirements for irradiance measurement, specimen backing, and normalization of test results.

- Measurement and analysis

- Sensitometric exposure, processing, densitometry, density correction methods and color‑balance assessment.

- Annexes provide interpolation methods, density corrections, data treatment and worked examples.

Practical applications and users

SIST ISO 18909:2023 is essential for:

- Conservation professionals and archives - to assess and plan long‑term storage and display strategies for colour photographs.

- Photographic material manufacturers and processors - for product development, quality control and specification of expected image life.

- Testing laboratories - to run reproducible accelerated ageing and light‑exposure tests and report standardized metrics.

- Museums, galleries and libraries - to evaluate risks from exhibition lighting, glazing, humidity and temperature and to set conservation policies.

- Photographers and repro labs - to understand fading risks and make informed choices about materials and display conditions.

Keywords: SIST ISO 18909:2023, image stability, photographic colour films, paper prints, dark stability, light stability, accelerated ageing, dye fading, colour balance, conservation.

Related Standards

- ISO 18936, ISO 18941, ISO 18946, ISO 18949 - dark stability tests for digitally printed reflection materials

- ISO 18937 series - light stability tests for digital prints

Frequently Asked Questions

SIST ISO 18909:2023 is a standard published by the Slovenian Institute for Standardization (SIST). Its full title is "Photography - Processed photographic colour films and paper prints - Methods for measuring image stability". This standard covers: This document describes test methods for determining the long-term dark storage stability of colour photographic images and the colour stability of such images when subjected to certain illuminants at specified temperatures and relative humidities. This document is applicable to colour photographic images made with traditional, continuous-tone photographic materials with images formed with dyes. These images are generated with chromogenic, silver dye-bleach, dye transfer, and dye-diffusion-transfer instant systems. The tests have not been verified for evaluating the stability of colour images produced with dry- and liquid-toner electrophotography, thermal dye transfer (sometimes called dye sublimation), ink jet, pigment-gelatin systems, offset lithography, gravure and related colour imaging systems. If these reflection print materials, including silver halide (chromogenic), are digitally printed, refer to ISO 18936, ISO 18941, ISO 18946, and ISO 18949 for dark stability tests, and the ISO 18937 series for light stability tests. This document does not include test procedures for the physical stability of images, supports or binder materials. However, it is recognized that in some instances, physical degradation such as support embrittlement, emulsion cracking or delamination of an image layer from its support, rather than image stability, will determine the useful life of a colour film or print material.

This document describes test methods for determining the long-term dark storage stability of colour photographic images and the colour stability of such images when subjected to certain illuminants at specified temperatures and relative humidities. This document is applicable to colour photographic images made with traditional, continuous-tone photographic materials with images formed with dyes. These images are generated with chromogenic, silver dye-bleach, dye transfer, and dye-diffusion-transfer instant systems. The tests have not been verified for evaluating the stability of colour images produced with dry- and liquid-toner electrophotography, thermal dye transfer (sometimes called dye sublimation), ink jet, pigment-gelatin systems, offset lithography, gravure and related colour imaging systems. If these reflection print materials, including silver halide (chromogenic), are digitally printed, refer to ISO 18936, ISO 18941, ISO 18946, and ISO 18949 for dark stability tests, and the ISO 18937 series for light stability tests. This document does not include test procedures for the physical stability of images, supports or binder materials. However, it is recognized that in some instances, physical degradation such as support embrittlement, emulsion cracking or delamination of an image layer from its support, rather than image stability, will determine the useful life of a colour film or print material.

SIST ISO 18909:2023 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 37.040.20 - Photographic paper, films and plates. Cartridges. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

SIST ISO 18909:2023 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to SIST ISO 18909:2011/Cor 1:2011, SIST ISO 18909:2011. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

SIST ISO 18909:2023 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-september-2023

Nadomešča:

SIST ISO 18909:2011

SIST ISO 18909:2011/Cor 1:2011

Fotografija - Procesirani barvni fotografski filmi in papirni natisi - Metode za

merjenje slikovne stabilnosti

Photography - Processed photographic colour films and paper prints - Methods for

measuring image stability

Photographie - Films et papiers photographiques couleur traités - Méthodes de mesure

de la stabilité de l'image

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: ISO 18909:2022

ICS:

37.040.20 Fotografski papir, filmi in Photographic paper, films

fotografske plošče. Filmski and plates. Cartridges

zvitki

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 18909

Second edition

2022-02

Photography — Processed

photographic colour films and paper

prints — Methods for measuring

image stability

Photographie — Films et papiers photographiques couleur traités —

Méthodes de mesure de la stabilité de l'image

Reference number

© ISO 2022

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may

be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on

the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below

or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

CP 401 • Ch. de Blandonnet 8

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva

Phone: +41 22 749 01 11

Email: copyright@iso.org

Website: www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii

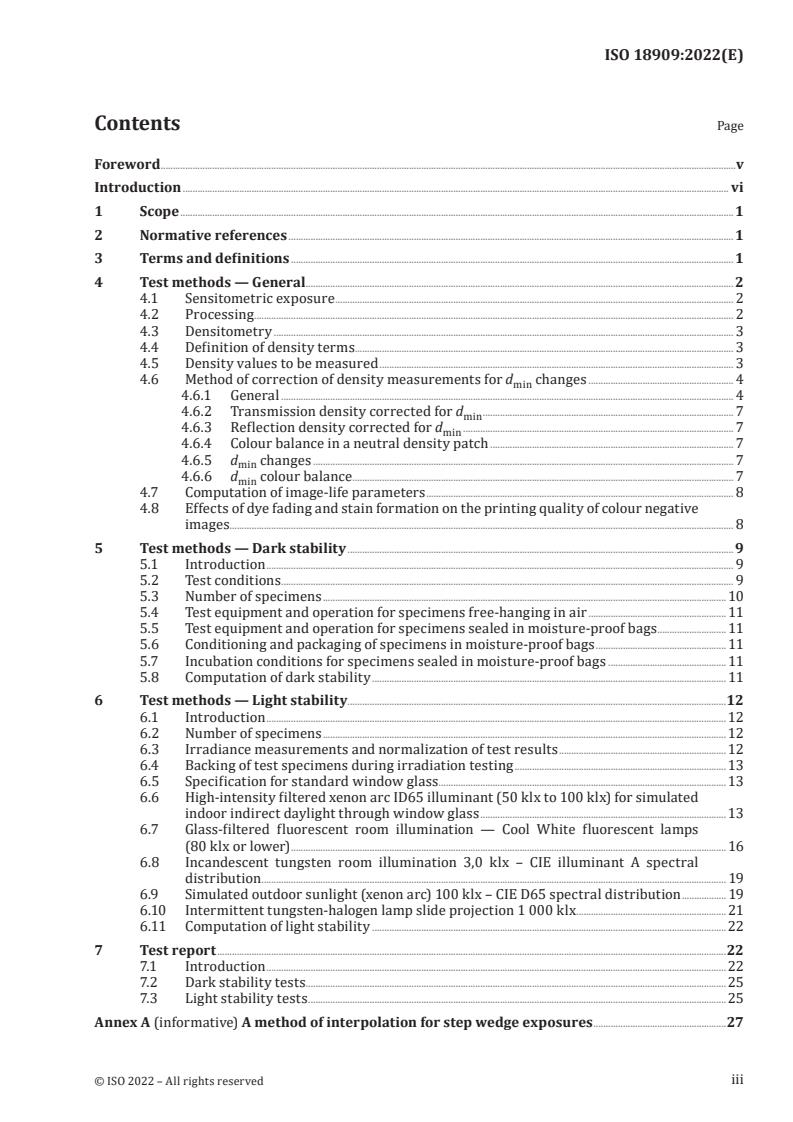

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction . vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Test methods — General . 2

4.1 Sensitometric exposure . 2

4.2 Processing . 2

4.3 Densitometry . 3

4.4 Definition of density terms . . 3

4.5 Density values to be measured . 3

4.6 Method of correction of density measurements for d changes . 4

min

4.6.1 General . 4

4.6.2 Transmission density corrected for d . 7

min

4.6.3 Reflection density corrected for d . 7

min

4.6.4 Colour balance in a neutral density patch . 7

4.6.5 d changes . 7

min

4.6.6 d colour balance . 7

min

4.7 Computation of image-life parameters . 8

4.8 Effects of dye fading and stain formation on the printing quality of colour negative

images. 8

5 Test methods — Dark stability .9

5.1 Introduction . 9

5.2 Test conditions . 9

5.3 Number of specimens . 10

5.4 Test equipment and operation for specimens free-hanging in air . 11

5.5 Test equipment and operation for specimens sealed in moisture-proof bags . 11

5.6 Conditioning and packaging of specimens in moisture-proof bags . 11

5.7 Incubation conditions for specimens sealed in moisture-proof bags . 11

5.8 Computation of dark stability . 11

6 Test methods — Light stability .12

6.1 Introduction . 12

6.2 Number of specimens . 12

6.3 Irradiance measurements and normalization of test results .12

6.4 Backing of test specimens during irradiation testing . 13

6.5 Specification for standard window glass . 13

6.6 High-intensity filtered xenon arc ID65 illuminant (50 klx to 100 klx) for simulated

indoor indirect daylight through window glass . 13

6.7 Glass-filtered fluorescent room illumination — Cool White fluorescent lamps

(80 klx or lower) . 16

6.8 Incandescent tungsten room illumination 3,0 klx – CIE illuminant A spectral

distribution . 19

6.9 Simulated outdoor sunlight (xenon arc) 100 klx – CIE D65 spectral distribution . 19

6.10 Intermittent tungsten-halogen lamp slide projection 1 000 klx . 21

6.11 Computation of light stability .22

7 Test report .22

7.1 Introduction . 22

7.2 Dark stability tests . . 25

7.3 Light stability tests . 25

Annex A (informative) A method of interpolation for step wedge exposures .27

iii

Annex B (informative) Method for power formula d correction of reflection print

min

materials .28

Annex C (informative) Illustration of Arrhenius calculation for dark stability .33

Annex D (informative) The importance of the starting density in the assessment of dye

fading and colour balance changes in light-stability tests .37

Annex E (informative) Enclosure effects in light-stability tests with prints framed under

glass or plastic sheets .39

Annex F (informative) Data treatment for the stability of light-exposed colour images .41

Bibliography .49

iv

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular, the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation of the voluntary nature of standards, the meaning of ISO specific terms and

expressions related to conformity assessment, as well as information about ISO's adherence to

the World Trade Organization (WTO) principles in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT), see

www.iso.org/iso/foreword.html.

This document was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 42, Photography.

This second edition cancels and replaces the first edition (ISO 18909:2006), of which it constitutes a

minor revision. The changes are as follows:

— a corrigendum published in 2006 has been incorporated, and

— updates have been made to align and compliment test methods for digital print materials.

Any feedback or questions on this document should be directed to the user’s national standards body. A

complete listing of these bodies can be found at www.iso.org/members.html.

v

Introduction

This document is divided into two parts. The first covers the methods and procedures for predicting

the long-term, dark storage stability of colour photographic images; the second covers the methods

and procedures for measuring the colour stability of such images when exposed to light of specified

intensities and spectral distribution, at specified temperatures and relative humidities.

Today, the majority of continuous-tone photographs are made with colour photographic materials. The

length of time that such photographs are to be kept can vary from a few days to many hundreds of

years and the importance of image stability can be correspondingly small or great. Often the ultimate

use of a particular photograph may not be known at the outset. Knowledge of the useful life of colour

photographs is important to many users, especially since stability requirements often vary depending

upon the application. For museums, archives, and others responsible for the care of colour photographic

materials, an understanding of the behaviour of these materials under various storage and display

conditions is essential if they are to be preserved in good condition for long periods of time.

Organic cyan, magenta and yellow dyes that are dispersed in transparent binder layers coated on to

transparent or white opaque supports form the images of most modern colour photographs. Colour

photographic dye images typically fade during storage and display; they will usually also change in

colour balance because the three image dyes seldom fade at the same rate. In addition, a yellowish (or

occasionally other colour) stain may form and physical degradation may occur, such as embrittlement

and cracking of the support and image layers. The rate of fading and staining can vary appreciably

and is governed principally by the intrinsic stability of the colour photographic material and by the

conditions under which the photograph is stored and displayed. The quality of chemical processing is

another important factor. Post-processing treatments, such as application of lacquers, plastic laminates

and retouching colours, may also affect the stability of colour materials.

The two main factors that influence storage behaviour, or dark stability, are the temperature and relative

humidity of the air that has access to the photograph. High temperature, particularly in combination

with high relative humidity, will accelerate the chemical reactions that can lead to degradation of one or

more of the image dyes. Low-temperature, low-humidity storage, on the other hand, can greatly prolong

the life of photographic colour images. Other potential causes of image degradation are atmospheric

pollutants (such as oxidizing and reducing gases), micro-organisms and insects.

Primarily the intensity of the illumination, the duration of exposure to light, the spectral distribution

of the illumination, and the ambient environmental conditions influence the stability of colour

photographs when displayed indoors or outdoors. (However, the normally slower dark fading and

staining reactions also proceed during display periods and will contribute to the total change in image

quality). Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is particularly harmful to some types of colour photographs and

can cause rapid fading as well as degradation of plastic layers such as the pigmented polyethylene layer

of resin-coated (RC) paper supports.

In practice, colour photographs are stored and displayed under varying combinations of temperature,

relative humidity and illumination, and for different lengths of time. For this reason, it is not possible to

precisely predict the useful life of a given type of photographic material unless the specific conditions

of storage and display are known in advance. Furthermore, the amount of change that is acceptable

differs greatly from viewer to viewer and is influenced by the type of scene and the tonal and colour

qualities of the image.

After extensive examination of amateur and professional colour photographs that have suffered varying

degrees of fading or staining, no consensus has been achieved on how much change is acceptable for

various image quality criteria. For this reason, this document does not specify acceptable end-points

for fading and changes in colour balance. Generally, however, the acceptable limits are twice as wide for

changes in overall image density as for changes in colour balance. For this reason, different criteria have

been used as examples in this document for predicting changes in image density and colour balance.

Pictorial tests can be helpful in assessing the visual changes that occur in light and dark stability tests,

but are not included in this document because no single scene is representative of the wide variety of

scenes actually encountered in photography.

vi

In dark storage at normal room temperatures, most modern colour films and papers have images that

fade and stain too slowly to allow evaluation of the dark storage stability simply by measuring changes

in the specimens over time. In such cases, too many years would be required to obtain meaningful

stability data. It is possible, however, to assess in a relatively short time the probable long-term fading

and staining behaviour at moderate or low temperatures by means of accelerated ageing tests carried

out at high temperatures. The influence of relative humidity also can be evaluated by conducting the

high-temperature tests at two or more humidity levels.

Similarly, information about the light stability of colour photographs can be obtained from accelerated

light-stability tests. These require special test units equipped with high-intensity light sources in

which test strips can be exposed for days, weeks, months or even years, to produce the desired amount

of image fading (or staining). The temperature of the specimens and their moisture content shall be

controlled throughout the test period, and the types of light sources shall be chosen to yield data that

can be correlated satisfactorily with those obtained under conditions of normal use.

Accelerated light stability tests for predicting the behaviour of photographic colour images under

normal display conditions may be complicated by reciprocity failure. When applied to light-induced

fading and staining of colour images, reciprocity failure refers to the failure of many dyes to fade, or

to form stain, equally when dyes are irradiated with high-intensity versus low-intensity light, even

though the total light exposure (intensity × time) is kept constant through appropriate adjustments

in exposure duration (see Reference [1]). The extent of dye fading and stain formation can be greater

or smaller under accelerated conditions, depending on the photochemical reactions involved in the

dye degradation, the kind of dye dispersion, the nature of the binder material, and other variables. For

example, the supply of oxygen that can diffuse from the surrounding atmosphere into a photograph's

image-containing emulsion layers may be restricted in an accelerated test (dry gelatin is an excellent

oxygen barrier). This may change the rate of dye-fading relative to that which would occur under normal

display conditions. The temperature and moisture content of the test specimen also influence the

magnitude of reciprocity failure. Furthermore, light fading is influenced by the pattern of irradiation

(continuous versus intermittent) as well as by light/dark cycling rates.

For all these reasons, long-term changes in image density, colour balance and stain level can be

reasonably estimated only for conditions similar to those employed in the accelerated tests, or when

good correlation has been confirmed between accelerated tests and actual conditions of use.

In order to establish the validity of the test methods for evaluating the dark and light stability of

different types of photographic colour films and papers, the following product types were selected for

the tests:

a) colour negative film with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

b) colour negative motion picture pre-print and negative films with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

c) colour reversal film with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

d) colour reversal film with incorporated Fischer-type couplers;

e) colour reversal film with couplers in the developers;

f) silver dye-bleach film and prints;

g) colour prints with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

h) colour motion picture print films with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

i) colour dye imbibition (dye transfer) prints;

j) integral colour instant print film with dye developers;

k) peel-apart colour instant print film with dye developers;

l) integral colour instant print film with dye releasers.

vii

The results of extensive tests with these materials showed that the methods and procedures of this

document can be used to obtain meaningful information about the long-term dark stability and the

light stability of colour photographs made with a specific product. They also can be used to compare

the stability of colour photographs made with different products and to access the effects of processing

variations or post-processing treatments. The accuracy of predictions made on the basis of such

accelerated ageing tests will depend greatly upon the actual storage or display conditions.

It should also be remembered that density changes induced by the test conditions and measured during

and after the tests include those in the film or paper support and in the various auxiliary layers that

may be included in a particular product. With most materials, however, the major changes occur in the

dye image layers.

Stability when stored in the dark

The tests for predicting the stability of colour photographic images in dark storage are based on an

[2][3]

adaptation of the Arrhenius method described by Bard et al. ) and earlier references by Arrhenius,

Steiger and others (see References [4], [5] and [6]). Although this method is derived from well-

understood and proven theoretical precepts of chemistry, the validity of its application for predicting

changes of photographic images rests on empirical confirmation. Although many chromogenic-type

colour products yield image-fading and staining data in both accelerated and non-accelerated dark

ageing tests that are in good agreement with the Arrhenius relationship, some other types of products

do not.

NOTE For example, integral-type instant colour print materials often exhibit atypical staining at elevated

temperatures; treatment of some chromogenic materials at temperatures above 80 °C and 60 % RH can cause

loss of incorporated high-boiling solvents and abnormal image degradation; and the dyes of silver dye-bleach

images deaggregate at combinations of very high temperature and high relative humidity, causing abnormal

changes in colour balance and saturation (see Reference [7]). In general, photographic materials tend to undergo

dramatic changes at relative humidities above 60 % (especially at the high temperatures employed in accelerated

tests) owing to changes in the physical properties of gelatin.

Stability when exposed to light

The methods of testing light stability in this document are based on the concept that increasing the light

intensity without changing the spectral distribution of the illuminant or the ambient temperature and

relative humidity should produce a proportional increase in the photochemical reactions that occur at

typical viewing or display conditions, without introducing any undesirable side effects.

However, because of reciprocity failures that are discussed in this Introduction, this assumption does

not always apply. Thus, the accelerated light stability test methods described in this document are

valid at the specified accelerated test conditions, but may not reliably predict the behaviours of a given

product in long-term display under normal conditions.

Translucent print materials, designed for viewing by either reflected or transmitted light (or a

combination of reflected and transmitted light), shall be evaluated as transparencies or as reflection

prints, depending on how they will be used. Data shall be reported for each condition of intended use.

This document does not specify which of the several light stability tests is the most important for any

particular product.

viii

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 18909:2022(E)

Photography — Processed photographic colour films and

paper prints — Methods for measuring image stability

1 Scope

This document describes test methods for determining the long-term dark storage stability of colour

photographic images and the colour stability of such images when subjected to certain illuminants at

specified temperatures and relative humidities.

This document is applicable to colour photographic images made with traditional, continuous-

tone photographic materials with images formed with dyes. These images are generated with

chromogenic, silver dye-bleach, dye transfer, and dye-diffusion-transfer instant systems. The tests

have not been verified for evaluating the stability of colour images produced with dry- and liquid-toner

electrophotography, thermal dye transfer (sometimes called dye sublimation), ink jet, pigment-gelatin

systems, offset lithography, gravure and related colour imaging systems. If these reflection print

materials, including silver halide (chromogenic), are digitally printed, refer to ISO 18936, ISO 18941,

ISO 18946, and ISO 18949 for dark stability tests, and the ISO 18937 series for light stability tests.

This document does not include test procedures for the physical stability of images, supports or binder

materials. However, it is recognized that in some instances, physical degradation such as support

embrittlement, emulsion cracking or delamination of an image layer from its support, rather than image

stability, will determine the useful life of a colour film or print material.

2 Normative references

The following documents are referred to in the text in such a way that some or all of their content

constitutes requirements of this document. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For

undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 5-2, Photography and graphic technology — Density measurements — Part 2: Geometric conditions for

transmittance density

ISO 5-3, Photography and graphic technology — Density measurements — Part 3: Spectral conditions

ISO 5-4, Photography and graphic technology — Density measurements — Part 4: Geometric conditions for

reflection density

ISO 18911, Imaging materials — Processed safety photographic films — Storage practices

ISO 18913, Imaging materials — Permanence — Vocabulary

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions given in ISO 18913 apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at https:// www .iso .org/ obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at https:// www .electropedia .org/

4 Test methods — General

4.1 Sensitometric exposure

The photographic material shall be exposed and processed in accordance with the manufacturer’s

recommendations to obtain areas (patches) of uniform density at least 5 mm × 5 mm. This document

requires measuring the changes in colour densities in minimum density areas, d , and at a density

min

of 1,0 ± 0,05 above d . These changes are to be monitored in neutral areas, i.e. where the initial red,

min

green and blue densities are approximately equal (above their respective d , as well as in areas

min

1)

selectively exposed to produce the purest possible cyan, magenta and yellow dye scales . These shall

be made with the aid of appropriate filters (see Table 1).

The desired density may be obtained from a single precise exposure or from a continuous wedge

exposure. Alternatively, if it is more convenient (e.g. with automated densitometry), the starting

densities of 1,0 above d may be interpolated from other densities (one way to do this is described in

min

Annex A).

Table 1 — Suitable filters for exposing test specimens

Filters to generate

a

b c

Type of material

(e.g. Kodak Wratten filters or Fuji filters )

Cyan dye Magenta dye Yellow dye

Minus red Minus green Minus blue

Wratten 32

Reversal and direct positive Wratten 44 Wratten 12

Fuji SP-4

Fuji SP-5 Fuji SC-50 or SC-52

or SP-12

Red Green Blue

Wratten 29 Wratten 99 Wratten 47B

Negative working

Fuji SC-62 Fuji BPN-55 Fuji BPB-42

a

If materials to be tested have unusual spectral sensitivity characteristics, consult the manufacturer for filter

recommendations.

b

Kodak Filters for Scientific and Technical Uses, Kodak Publication No. B-3, Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, New York,

USA; 1985. This information is given for the convenience of users of this document and does not constitute an endorsement

by ISO of the product named. Equivalent products may be used if they can be shown to lead to the same results.

c

Fujifilm Filter “Optical," Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; 1993. This information is given for the convenience of

users of this document and does not constitute an endorsement by ISO of the product named. Equivalent products may be

used if they can be shown to lead to the same results.

4.2 Processing

The sensitometrically exposed specimens shall be processed using the processing system of primary

interest.

The processing chemicals and processing procedure can have a significant effect on the dark-keeping

and/or light-keeping stability of a colour photographic material. For example, a chromogenic colour

negative print paper processed in a washless or non-plumbed system with a stabilizer rinse bath

instead of a water wash probably has stability characteristics that are different from the same colour

paper processed in a conventional chemistry and a final water wash. Therefore, the specific processing

chemicals and procedure shall be listed along with the name of the colour product in any reference to

the test results.

1) Because of optical or chemical interactions, a neutral patch or a patch with a colour composed of a mixture of

two dyes, e.g. red, green or blue, often exhibit stability effects that are different from pure cyan, magenta or yellow

dye patches. This situation is particularly likely to occur when images are subjected to light fading.

Stability data obtained from a colour material processed in certain processing chemicals shall not

be applied to the colour material processed in different chemicals, or using a different processing

procedure. Likewise, data obtained from test specimens shall not be applied to colour materials that

have been subjected to post-processing treatments (e.g. application of lacquers, plastic laminates or

retouching colours) that differ from the treatments given to the test specimens.

4.3 Densitometry

Image density shall be measured with the spectral conditions specified for Status A densitometry

(transparencies and reflection prints) and for Status M densitometry (negatives) as described in ISO 5-3.

Transmission density, D , (90° opal; S: < 10°; s) shall be measured with an instrument complying with

T

the geometric conditions described in ISO 5-2. Reflection density, D , (40° to 50°; S: 5°; s) shall be

R

measured as described in ISO 5-4.

One of the problems encountered in densitometry is the instability of the measuring devices, especially

during the course of long-term tests. Some of the components of densitometers that can change

appreciably with age, as well as from one unit or batch to another, are the optical filters, the light sensors

and the lamps. For example, the filters in many modern densitometers will deteriorate with age and

shall be replaced periodically, often within 2 years to 3 years. However, replacement filters of the same

type frequently do not exactly match the original filters in spectral transmittance characteristics. Such

changes in transmittance will cause unequal changes in the measured density values of dyes having

different spectral absorption properties.

One way of dealing with such problems in a densitometer system is to keep standard reference

specimens of each test product sealed in vapour-proof containers and stored at −18 °C or lower. These

specimens can be used to check the performance of the system periodically and to derive correction

factors for different products as required (the calibration standards supplied with a densitometer are

not adequate for this purpose).

4.4 Definition of density terms

d is the symbol for measured density;

D is the symbol for density corrected for d .

min

4.5 Density values to be measured

The following densities of the specimens, prepared as described in 4.1, shall be measured before and

after the treatment interval (see Figure 1):

a) d (R) , d (G) , d (B)

min t min t min t

the red, green and blue minimum densities of specimens that have been treated for time t, where t

takes on values from 0 to the end of the test;

b) d (R) , d (G) , d (B)

N t N t N t

the red, green and blue densities of neutral patches that initially had densities of 1,0 above d and that

min

have been treated for time t, where t takes on values from 0 to the end of the test;

c) d (R) , d (G) , d (B)

C t M t Y t

the red, green and blue densities of cyan, magenta and yellow colour patches that initially had densities

of 1,0 above d and that have been treated for time t, where t takes on values from 0 to the end of the

min

test.

4.6 Method of correction of density measurements for d changes

min

4.6.1 General

The areas of minimum density of many types of colour photographs change with time during dark

storage, and generally to a lesser extent also change on prolonged exposure to light during display or

projection. Such changes most commonly take the form of density (stain) increases, usually yellowish in

colour. However, some materials, under certain conditions, may exhibit a loss in minimum density; e.g.

colour negatives in dark storage.

For the purposes of this document, changes in minimum density as measured in d patches, whether

min

increases or losses, are assumed to have occurred equally at all density levels. Therefore, in order to

determine accurately the amount of dye-fading that has taken place during testing or during storage

and display, it is necessary to take into account the change in the d value (see Table 2).

min

a

Table 2 — Correction of density measurements for d changes

min

Type of material and test Correction

Transmission materials in dark and light stability tests Full d correction (for starting density of 1,0 above

min

d )

min

1/2 d correction (for starting densities of 0,7 to

min

Reflection materials in dark and light stability tests

1,0 above d )

min

Reflection materials in dark and light stability tests

d correction by power formula

min

(alternative method – see Annex B)

a

No correction is made for d changes when determining colour balance changes of neutral patches.

min

Different methods of d correction are specified for transmission and reflection materials because

min

multiple internal reflections affect the d density values obtained with reflection materials, but not

min

those of transmission materials (see References [8] and [9]). Specifically, the multiple reflections within

the image and auxiliary layers of a reflection material cause an increase in the measured value of the

stain density, but have much less effect on the measured values of reflection densities in the range of 0,7

to 1,0 above d . It was determined empirically that one-half the change measured in the d value of

min min

reflection materials provides a reasonable approximation of the actual d contribution to measured

min

reflection densities in the range of 0,7 to 1,0 above d .

min

For translucent materials the most common method of density measurement is transmission; however,

these materials shall be measured by reflection if that is their intended use. Translucent materials with

very high initial transmission d may show a loss of d with light or dark treatment. In these cases,

min min

the use of half d correction may confound the measurements and caution shall be used.

min

An alternative method for d correction using a multi-power relationship among stain, dye and

min

measured densities is described in Annex B. This method is particularly useful for the correction of

measured densities when relatively high stain levels are present and/or when measuring low-density

levels below 0,7.

Two examples are described in a) and b) to help clarity the d correction procedures (illustrated in

min

Figure 1 for transmission materials and Figure 2 for reflection materials).

Key

X log of exposure

Y transmission density

1 before testing

2 after testing

Figure 1 — Illustration of the blue transmission density of a neutral patch of

a transparency-type colour material (as defined by formulae in 4.6.2)

a) A colour transparency material tested for dark stability had a neutral patch with a starting blue

density D (B) of 1,0 since:

N o

d (B) = 1,1

N o

d (B) = 0,1, and therefore

min o

D (B) = [d (B) − d (B) ] = 1,1 − 0,1 = 1,0

N o N o min o

After incubation for time t, the blue density D (B) was 0,72 because the measured density values had

N t

changed as follows:

d (B) = 0,90

N t

d (B) = 0,18, and therefore

min t

D (B) = [d (B) − d (B) ] = 0,90 − 0,18 = 0,72

N t N t min t

Hence, the blue density of the neutral patch decreased by 0,28, whereas that of the minimum density

patch increased (due to formation of yellowish stain) by 0,08. If the d value had increased less,

min

or even decreased (as can occur with colour negative films, for example), the value of d (B) would

N t

have changed by a different, commensurate amount. However, by subtracting the d density from

min

the density of the neutral patch, both before and after incubation, the actual change in density of the

neutral patch is determined. Similar procedures are employed to correct the cyan, magenta and yellow

patches for d changes.

min

Key

X log of exposure

Y refection density

1 before testing

2 after testing

Figure 2 — Illustration of the blue reflection density of a neutral patch of

a reflection-type colour material (as defined by formulae in 4.6.3)

b) A colour reflection print material tested for dark stability had a neutral patch with a starting blue

density D (B) of 1,0 since:

N o

d (B) = 1,1

N o

d (B) = 0,1, and therefore

min o

D (B) = [d (B) − d (B) ] = 1,1 − 0,1 = 1,0

N o N o min o

After incubation for time t, the blue density D (B) was 0,76 because the measured density values had

N t

changed as follows:

d (B) = 0,90

N t

d (B) = 0,18, and therefore

min t

D (B) = d (B) − d (B) + ½ [d (B) − d (B) ] = 0,90 − 0,18 + ½ (0,18 − 0,10) = 0,72 + 0,04 = 0,76

N t N t min t min t min o

Hence, the blue density of the neutral patch decreased by 0,24, whereas that of the minimum density

patch increased (due to formation of yellowish stain) by 0,08. However, this increase in the measured

d value was due in part to the effects of multiple internal reflections, as explained in 4.5. Therefore,

min

a correction was made equal to + ½ the measured change of 0,08. Such a correction of + ½ d change

min

would also have to be made if the d value had decreased rather than increased. Similar procedures

min

are employed to correct the cyan, magenta and yellow patches for d changes.

min

NOTE The gradient of the two curves of Figure 2 was deliberately lowered in order to provide a clearer view

of the density relations defined in the formula.

4.6.2 Transmission density corrected for d

min

a) D (R) = d (R) − d (R)

N t N t min t

b) D (G) = d (G) − d (G)

N t N t min t

c) D (B) = d (B) − d (B)

N t N t min t

d) D (R) = d (R) − d (R)

C t C t min t

e) D (G) = d (G) − d (G)

M t M t min t

f) D (B) = d (B) − d (B)

Y t Y t min t

4.6.3 Reflection density corrected for d

min

a) D (R) = d (R) − d (R) +1/2 [d (R) − d (R) ]

N t N t min t min t min o

b) D (G) = d (G) − d (G) +1/2 [d (G) − d (G) ]

N t N t min t min t min o

c) D (B) = d (B) − d (B) +1/2 [d (B) − d (B) ]

N t N t min t min t min o

d) D (R) = d (R) − d (R) +1/2[d (R) − d (R) ]

C t C t min t min t min o

e) D (G) = d (G) − d (G) +1/2 [d (G) − d (G) ]

M t M t min t min t min o

f) D (B) = d (B) − d (B) +1/2 [d (B) − d (B) ]

Y t Y t min t min t min o

NOTE The d correction for reflection density is identical to that for transmission density, except that it

min

includes a back correction equal to one half the d gain.

min

4.6.4 Colour balance in a neutral density patch

These are calculated as the percent of the average density.

dd()RG− ()

NNtt

a) d ()RG−= × 100 %

N t

05,[dd()R + (G) ]

NNtt

dd(

...

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 18909

Second edition

2022-02

Photography — Processed

photographic colour films and paper

prints — Methods for measuring

image stability

Photographie — Films et papiers photographiques couleur traités —

Méthodes de mesure de la stabilité de l'image

Reference number

© ISO 2022

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may

be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on

the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below

or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

CP 401 • Ch. de Blandonnet 8

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva

Phone: +41 22 749 01 11

Email: copyright@iso.org

Website: www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction . vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Test methods — General . 2

4.1 Sensitometric exposure . 2

4.2 Processing . 2

4.3 Densitometry . 3

4.4 Definition of density terms . . 3

4.5 Density values to be measured . 3

4.6 Method of correction of density measurements for d changes . 4

min

4.6.1 General . 4

4.6.2 Transmission density corrected for d . 7

min

4.6.3 Reflection density corrected for d . 7

min

4.6.4 Colour balance in a neutral density patch . 7

4.6.5 d changes . 7

min

4.6.6 d colour balance . 7

min

4.7 Computation of image-life parameters . 8

4.8 Effects of dye fading and stain formation on the printing quality of colour negative

images. 8

5 Test methods — Dark stability .9

5.1 Introduction . 9

5.2 Test conditions . 9

5.3 Number of specimens . 10

5.4 Test equipment and operation for specimens free-hanging in air . 11

5.5 Test equipment and operation for specimens sealed in moisture-proof bags . 11

5.6 Conditioning and packaging of specimens in moisture-proof bags . 11

5.7 Incubation conditions for specimens sealed in moisture-proof bags . 11

5.8 Computation of dark stability . 11

6 Test methods — Light stability .12

6.1 Introduction . 12

6.2 Number of specimens . 12

6.3 Irradiance measurements and normalization of test results .12

6.4 Backing of test specimens during irradiation testing . 13

6.5 Specification for standard window glass . 13

6.6 High-intensity filtered xenon arc ID65 illuminant (50 klx to 100 klx) for simulated

indoor indirect daylight through window glass . 13

6.7 Glass-filtered fluorescent room illumination — Cool White fluorescent lamps

(80 klx or lower) . 16

6.8 Incandescent tungsten room illumination 3,0 klx – CIE illuminant A spectral

distribution . 19

6.9 Simulated outdoor sunlight (xenon arc) 100 klx – CIE D65 spectral distribution . 19

6.10 Intermittent tungsten-halogen lamp slide projection 1 000 klx . 21

6.11 Computation of light stability .22

7 Test report .22

7.1 Introduction . 22

7.2 Dark stability tests . . 25

7.3 Light stability tests . 25

Annex A (informative) A method of interpolation for step wedge exposures .27

iii

Annex B (informative) Method for power formula d correction of reflection print

min

materials .28

Annex C (informative) Illustration of Arrhenius calculation for dark stability .33

Annex D (informative) The importance of the starting density in the assessment of dye

fading and colour balance changes in light-stability tests .37

Annex E (informative) Enclosure effects in light-stability tests with prints framed under

glass or plastic sheets .39

Annex F (informative) Data treatment for the stability of light-exposed colour images .41

Bibliography .49

iv

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular, the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation of the voluntary nature of standards, the meaning of ISO specific terms and

expressions related to conformity assessment, as well as information about ISO's adherence to

the World Trade Organization (WTO) principles in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT), see

www.iso.org/iso/foreword.html.

This document was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 42, Photography.

This second edition cancels and replaces the first edition (ISO 18909:2006), of which it constitutes a

minor revision. The changes are as follows:

— a corrigendum published in 2006 has been incorporated, and

— updates have been made to align and compliment test methods for digital print materials.

Any feedback or questions on this document should be directed to the user’s national standards body. A

complete listing of these bodies can be found at www.iso.org/members.html.

v

Introduction

This document is divided into two parts. The first covers the methods and procedures for predicting

the long-term, dark storage stability of colour photographic images; the second covers the methods

and procedures for measuring the colour stability of such images when exposed to light of specified

intensities and spectral distribution, at specified temperatures and relative humidities.

Today, the majority of continuous-tone photographs are made with colour photographic materials. The

length of time that such photographs are to be kept can vary from a few days to many hundreds of

years and the importance of image stability can be correspondingly small or great. Often the ultimate

use of a particular photograph may not be known at the outset. Knowledge of the useful life of colour

photographs is important to many users, especially since stability requirements often vary depending

upon the application. For museums, archives, and others responsible for the care of colour photographic

materials, an understanding of the behaviour of these materials under various storage and display

conditions is essential if they are to be preserved in good condition for long periods of time.

Organic cyan, magenta and yellow dyes that are dispersed in transparent binder layers coated on to

transparent or white opaque supports form the images of most modern colour photographs. Colour

photographic dye images typically fade during storage and display; they will usually also change in

colour balance because the three image dyes seldom fade at the same rate. In addition, a yellowish (or

occasionally other colour) stain may form and physical degradation may occur, such as embrittlement

and cracking of the support and image layers. The rate of fading and staining can vary appreciably

and is governed principally by the intrinsic stability of the colour photographic material and by the

conditions under which the photograph is stored and displayed. The quality of chemical processing is

another important factor. Post-processing treatments, such as application of lacquers, plastic laminates

and retouching colours, may also affect the stability of colour materials.

The two main factors that influence storage behaviour, or dark stability, are the temperature and relative

humidity of the air that has access to the photograph. High temperature, particularly in combination

with high relative humidity, will accelerate the chemical reactions that can lead to degradation of one or

more of the image dyes. Low-temperature, low-humidity storage, on the other hand, can greatly prolong

the life of photographic colour images. Other potential causes of image degradation are atmospheric

pollutants (such as oxidizing and reducing gases), micro-organisms and insects.

Primarily the intensity of the illumination, the duration of exposure to light, the spectral distribution

of the illumination, and the ambient environmental conditions influence the stability of colour

photographs when displayed indoors or outdoors. (However, the normally slower dark fading and

staining reactions also proceed during display periods and will contribute to the total change in image

quality). Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is particularly harmful to some types of colour photographs and

can cause rapid fading as well as degradation of plastic layers such as the pigmented polyethylene layer

of resin-coated (RC) paper supports.

In practice, colour photographs are stored and displayed under varying combinations of temperature,

relative humidity and illumination, and for different lengths of time. For this reason, it is not possible to

precisely predict the useful life of a given type of photographic material unless the specific conditions

of storage and display are known in advance. Furthermore, the amount of change that is acceptable

differs greatly from viewer to viewer and is influenced by the type of scene and the tonal and colour

qualities of the image.

After extensive examination of amateur and professional colour photographs that have suffered varying

degrees of fading or staining, no consensus has been achieved on how much change is acceptable for

various image quality criteria. For this reason, this document does not specify acceptable end-points

for fading and changes in colour balance. Generally, however, the acceptable limits are twice as wide for

changes in overall image density as for changes in colour balance. For this reason, different criteria have

been used as examples in this document for predicting changes in image density and colour balance.

Pictorial tests can be helpful in assessing the visual changes that occur in light and dark stability tests,

but are not included in this document because no single scene is representative of the wide variety of

scenes actually encountered in photography.

vi

In dark storage at normal room temperatures, most modern colour films and papers have images that

fade and stain too slowly to allow evaluation of the dark storage stability simply by measuring changes

in the specimens over time. In such cases, too many years would be required to obtain meaningful

stability data. It is possible, however, to assess in a relatively short time the probable long-term fading

and staining behaviour at moderate or low temperatures by means of accelerated ageing tests carried

out at high temperatures. The influence of relative humidity also can be evaluated by conducting the

high-temperature tests at two or more humidity levels.

Similarly, information about the light stability of colour photographs can be obtained from accelerated

light-stability tests. These require special test units equipped with high-intensity light sources in

which test strips can be exposed for days, weeks, months or even years, to produce the desired amount

of image fading (or staining). The temperature of the specimens and their moisture content shall be

controlled throughout the test period, and the types of light sources shall be chosen to yield data that

can be correlated satisfactorily with those obtained under conditions of normal use.

Accelerated light stability tests for predicting the behaviour of photographic colour images under

normal display conditions may be complicated by reciprocity failure. When applied to light-induced

fading and staining of colour images, reciprocity failure refers to the failure of many dyes to fade, or

to form stain, equally when dyes are irradiated with high-intensity versus low-intensity light, even

though the total light exposure (intensity × time) is kept constant through appropriate adjustments

in exposure duration (see Reference [1]). The extent of dye fading and stain formation can be greater

or smaller under accelerated conditions, depending on the photochemical reactions involved in the

dye degradation, the kind of dye dispersion, the nature of the binder material, and other variables. For

example, the supply of oxygen that can diffuse from the surrounding atmosphere into a photograph's

image-containing emulsion layers may be restricted in an accelerated test (dry gelatin is an excellent

oxygen barrier). This may change the rate of dye-fading relative to that which would occur under normal

display conditions. The temperature and moisture content of the test specimen also influence the

magnitude of reciprocity failure. Furthermore, light fading is influenced by the pattern of irradiation

(continuous versus intermittent) as well as by light/dark cycling rates.

For all these reasons, long-term changes in image density, colour balance and stain level can be

reasonably estimated only for conditions similar to those employed in the accelerated tests, or when

good correlation has been confirmed between accelerated tests and actual conditions of use.

In order to establish the validity of the test methods for evaluating the dark and light stability of

different types of photographic colour films and papers, the following product types were selected for

the tests:

a) colour negative film with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

b) colour negative motion picture pre-print and negative films with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

c) colour reversal film with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

d) colour reversal film with incorporated Fischer-type couplers;

e) colour reversal film with couplers in the developers;

f) silver dye-bleach film and prints;

g) colour prints with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

h) colour motion picture print films with incorporated oil-soluble couplers;

i) colour dye imbibition (dye transfer) prints;

j) integral colour instant print film with dye developers;

k) peel-apart colour instant print film with dye developers;

l) integral colour instant print film with dye releasers.

vii

The results of extensive tests with these materials showed that the methods and procedures of this

document can be used to obtain meaningful information about the long-term dark stability and the

light stability of colour photographs made with a specific product. They also can be used to compare

the stability of colour photographs made with different products and to access the effects of processing

variations or post-processing treatments. The accuracy of predictions made on the basis of such

accelerated ageing tests will depend greatly upon the actual storage or display conditions.

It should also be remembered that density changes induced by the test conditions and measured during

and after the tests include those in the film or paper support and in the various auxiliary layers that

may be included in a particular product. With most materials, however, the major changes occur in the

dye image layers.

Stability when stored in the dark

The tests for predicting the stability of colour photographic images in dark storage are based on an

[2][3]

adaptation of the Arrhenius method described by Bard et al. ) and earlier references by Arrhenius,

Steiger and others (see References [4], [5] and [6]). Although this method is derived from well-

understood and proven theoretical precepts of chemistry, the validity of its application for predicting

changes of photographic images rests on empirical confirmation. Although many chromogenic-type

colour products yield image-fading and staining data in both accelerated and non-accelerated dark

ageing tests that are in good agreement with the Arrhenius relationship, some other types of products

do not.

NOTE For example, integral-type instant colour print materials often exhibit atypical staining at elevated

temperatures; treatment of some chromogenic materials at temperatures above 80 °C and 60 % RH can cause

loss of incorporated high-boiling solvents and abnormal image degradation; and the dyes of silver dye-bleach

images deaggregate at combinations of very high temperature and high relative humidity, causing abnormal

changes in colour balance and saturation (see Reference [7]). In general, photographic materials tend to undergo

dramatic changes at relative humidities above 60 % (especially at the high temperatures employed in accelerated

tests) owing to changes in the physical properties of gelatin.

Stability when exposed to light

The methods of testing light stability in this document are based on the concept that increasing the light

intensity without changing the spectral distribution of the illuminant or the ambient temperature and

relative humidity should produce a proportional increase in the photochemical reactions that occur at

typical viewing or display conditions, without introducing any undesirable side effects.

However, because of reciprocity failures that are discussed in this Introduction, this assumption does

not always apply. Thus, the accelerated light stability test methods described in this document are

valid at the specified accelerated test conditions, but may not reliably predict the behaviours of a given

product in long-term display under normal conditions.

Translucent print materials, designed for viewing by either reflected or transmitted light (or a

combination of reflected and transmitted light), shall be evaluated as transparencies or as reflection

prints, depending on how they will be used. Data shall be reported for each condition of intended use.

This document does not specify which of the several light stability tests is the most important for any

particular product.

viii

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 18909:2022(E)

Photography — Processed photographic colour films and

paper prints — Methods for measuring image stability

1 Scope

This document describes test methods for determining the long-term dark storage stability of colour

photographic images and the colour stability of such images when subjected to certain illuminants at

specified temperatures and relative humidities.

This document is applicable to colour photographic images made with traditional, continuous-

tone photographic materials with images formed with dyes. These images are generated with

chromogenic, silver dye-bleach, dye transfer, and dye-diffusion-transfer instant systems. The tests

have not been verified for evaluating the stability of colour images produced with dry- and liquid-toner

electrophotography, thermal dye transfer (sometimes called dye sublimation), ink jet, pigment-gelatin

systems, offset lithography, gravure and related colour imaging systems. If these reflection print

materials, including silver halide (chromogenic), are digitally printed, refer to ISO 18936, ISO 18941,

ISO 18946, and ISO 18949 for dark stability tests, and the ISO 18937 series for light stability tests.

This document does not include test procedures for the physical stability of images, supports or binder

materials. However, it is recognized that in some instances, physical degradation such as support

embrittlement, emulsion cracking or delamination of an image layer from its support, rather than image

stability, will determine the useful life of a colour film or print material.

2 Normative references

The following documents are referred to in the text in such a way that some or all of their content

constitutes requirements of this document. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For

undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 5-2, Photography and graphic technology — Density measurements — Part 2: Geometric conditions for

transmittance density

ISO 5-3, Photography and graphic technology — Density measurements — Part 3: Spectral conditions

ISO 5-4, Photography and graphic technology — Density measurements — Part 4: Geometric conditions for

reflection density

ISO 18911, Imaging materials — Processed safety photographic films — Storage practices

ISO 18913, Imaging materials — Permanence — Vocabulary

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions given in ISO 18913 apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at https:// www .iso .org/ obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at https:// www .electropedia .org/

4 Test methods — General

4.1 Sensitometric exposure

The photographic material shall be exposed and processed in accordance with the manufacturer’s

recommendations to obtain areas (patches) of uniform density at least 5 mm × 5 mm. This document

requires measuring the changes in colour densities in minimum density areas, d , and at a density

min

of 1,0 ± 0,05 above d . These changes are to be monitored in neutral areas, i.e. where the initial red,

min

green and blue densities are approximately equal (above their respective d , as well as in areas

min

1)

selectively exposed to produce the purest possible cyan, magenta and yellow dye scales . These shall

be made with the aid of appropriate filters (see Table 1).

The desired density may be obtained from a single precise exposure or from a continuous wedge

exposure. Alternatively, if it is more convenient (e.g. with automated densitometry), the starting

densities of 1,0 above d may be interpolated from other densities (one way to do this is described in

min

Annex A).

Table 1 — Suitable filters for exposing test specimens

Filters to generate

a

b c

Type of material

(e.g. Kodak Wratten filters or Fuji filters )

Cyan dye Magenta dye Yellow dye

Minus red Minus green Minus blue

Wratten 32

Reversal and direct positive Wratten 44 Wratten 12

Fuji SP-4

Fuji SP-5 Fuji SC-50 or SC-52

or SP-12

Red Green Blue

Wratten 29 Wratten 99 Wratten 47B

Negative working

Fuji SC-62 Fuji BPN-55 Fuji BPB-42

a

If materials to be tested have unusual spectral sensitivity characteristics, consult the manufacturer for filter

recommendations.

b

Kodak Filters for Scientific and Technical Uses, Kodak Publication No. B-3, Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, New York,

USA; 1985. This information is given for the convenience of users of this document and does not constitute an endorsement

by ISO of the product named. Equivalent products may be used if they can be shown to lead to the same results.

c

Fujifilm Filter “Optical," Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; 1993. This information is given for the convenience of

users of this document and does not constitute an endorsement by ISO of the product named. Equivalent products may be

used if they can be shown to lead to the same results.

4.2 Processing

The sensitometrically exposed specimens shall be processed using the processing system of primary

interest.

The processing chemicals and processing procedure can have a significant effect on the dark-keeping

and/or light-keeping stability of a colour photographic material. For example, a chromogenic colour

negative print paper processed in a washless or non-plumbed system with a stabilizer rinse bath

instead of a water wash probably has stability characteristics that are different from the same colour

paper processed in a conventional chemistry and a final water wash. Therefore, the specific processing

chemicals and procedure shall be listed along with the name of the colour product in any reference to

the test results.

1) Because of optical or chemical interactions, a neutral patch or a patch with a colour composed of a mixture of

two dyes, e.g. red, green or blue, often exhibit stability effects that are different from pure cyan, magenta or yellow

dye patches. This situation is particularly likely to occur when images are subjected to light fading.

Stability data obtained from a colour material processed in certain processing chemicals shall not

be applied to the colour material processed in different chemicals, or using a different processing

procedure. Likewise, data obtained from test specimens shall not be applied to colour materials that

have been subjected to post-processing treatments (e.g. application of lacquers, plastic laminates or

retouching colours) that differ from the treatments given to the test specimens.

4.3 Densitometry

Image density shall be measured with the spectral conditions specified for Status A densitometry

(transparencies and reflection prints) and for Status M densitometry (negatives) as described in ISO 5-3.

Transmission density, D , (90° opal; S: < 10°; s) shall be measured with an instrument complying with

T

the geometric conditions described in ISO 5-2. Reflection density, D , (40° to 50°; S: 5°; s) shall be

R

measured as described in ISO 5-4.

One of the problems encountered in densitometry is the instability of the measuring devices, especially

during the course of long-term tests. Some of the components of densitometers that can change

appreciably with age, as well as from one unit or batch to another, are the optical filters, the light sensors

and the lamps. For example, the filters in many modern densitometers will deteriorate with age and

shall be replaced periodically, often within 2 years to 3 years. However, replacement filters of the same

type frequently do not exactly match the original filters in spectral transmittance characteristics. Such

changes in transmittance will cause unequal changes in the measured density values of dyes having

different spectral absorption properties.

One way of dealing with such problems in a densitometer system is to keep standard reference

specimens of each test product sealed in vapour-proof containers and stored at −18 °C or lower. These

specimens can be used to check the performance of the system periodically and to derive correction

factors for different products as required (the calibration standards supplied with a densitometer are

not adequate for this purpose).

4.4 Definition of density terms

d is the symbol for measured density;

D is the symbol for density corrected for d .

min

4.5 Density values to be measured

The following densities of the specimens, prepared as described in 4.1, shall be measured before and

after the treatment interval (see Figure 1):

a) d (R) , d (G) , d (B)

min t min t min t

the red, green and blue minimum densities of specimens that have been treated for time t, where t

takes on values from 0 to the end of the test;

b) d (R) , d (G) , d (B)

N t N t N t

the red, green and blue densities of neutral patches that initially had densities of 1,0 above d and that

min

have been treated for time t, where t takes on values from 0 to the end of the test;