ISO 22901-1:2008

(Main)Road vehicles — Open diagnostic data exchange (ODX) — Part 1: Data model specification

Road vehicles — Open diagnostic data exchange (ODX) — Part 1: Data model specification

ISO 22901-1:2008 specifies the concept of using a new industry standard diagnostic format to make diagnostic data stream information available to diagnostic tool application manufacturers, in order to simplify the support of the aftermarket automotive service industry. The Open Diagnostic Data Exchange (ODX) modelled diagnostic data are compatible with the software requirements of the Modular Vehicle Communication Interface (MVCI), as specified in ISO 22900-2 and ISO 22900-3. The ODX modelled diagnostic data will enable an MVCI device to communicate with the vehicle Electronic Control Unit(s) (ECU) and interpret the diagnostic data contained in the messages exchanged between the external test equipment and the ECU(s). For ODX compliant external test equipment, no software programming is necessary to convert diagnostic data into technician readable information to be displayed by the tester. The ODX specification contains the data model to describe all diagnostic data of a vehicle and physical ECU, e.g. diagnostic trouble codes, data parameters, identification data, input/output parameters, ECU configuration (variant coding) data and communication parameters. ODX is described in Unified Modelling Language (UML) diagrams and the data exchange format uses Extensible Mark-up Language (XML). The ODX modelled diagnostic data describe: protocol specification for diagnostic communication of ECUs; communication parameters for different protocols and data link layers and for ECU software; ECU programming data (Flash); related vehicle interface description (connectors and pinout); functional description of diagnostic capabilities of a network of ECUs; ECU configuration data (variant coding). The purpose of ISO 22901-1:2008 is to ensure that diagnostic data from any vehicle manufacturer is independent of the testing hardware and protocol software supplied by any test equipment manufacturer.

Véhicules routiers — Échange de données de diagnostic ouvert (ODX) — Partie 1: Spécification de modèle de données

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 05-Nov-2008

- Technical Committee

- ISO/TC 22/SC 31 - Data communication

- Drafting Committee

- ISO/TC 22/SC 31/WG 5 - Test equipment/Data eXchange Formats

- Current Stage

- 9093 - International Standard confirmed

- Start Date

- 02-Jul-2025

- Completion Date

- 14-Feb-2026

Overview

ISO 22901-1:2008 - "Road vehicles - Open diagnostic data exchange (ODX) - Part 1: Data model specification" defines a vendor-neutral diagnostic data model to standardize how vehicle diagnostic information is described and exchanged. The standard makes diagnostic data stream information available to diagnostic tool manufacturers to simplify aftermarket support and ensure that diagnostic content is independent of testing hardware or protocol software.

ODX-modeled diagnostic data are described in UML diagrams and exchanged using XML, enabling external test equipment (diagnostic testers) to interpret messages exchanged with vehicle Electronic Control Units (ECUs) without custom programming. ISO 22901-1 aligns with the Modular Vehicle Communication Interface (MVCI) software requirements as specified in ISO 22900-2 and ISO 22900-3.

Key Topics and Requirements

- Data model specification: Structured representation of all vehicle/ECU diagnostic data for consistent interpretation.

- Diagnostic data types covered:

- Diagnostic trouble codes (DTCs)

- Data parameters and input/output parameters

- Identification and configuration (variant coding) data

- ECU programming (Flash) data

- Communication parameters for protocols and data link layers

- Vehicle interface descriptions (connectors, pinouts)

- Functional descriptions of diagnostic capabilities across ECU networks

- Format and modelling: Uses UML diagrams for the conceptual model and XML for data exchange files.

- Interoperability requirement: Ensures diagnostic content is hardware- and protocol-independent, enabling MVCI-compliant devices to communicate and interpret ECU diagnostic messages without bespoke software conversion.

Applications and Who Uses It

- Aftermarket diagnostic tool manufacturers: Build testers that load ODX files to present readable information to technicians without custom protocol coding.

- Automotive diagnostic software developers: Implement support for ODX XML files and UML-derived structures to interpret ECU data.

- Vehicle OEMs and Tier suppliers: Publish diagnostic descriptions in ODX format to support authorized repair and service ecosystems.

- Service networks and repair shops: Use ODX-compliant testers to diagnose, program, and configure ECUs across vehicle makes and models.

- Benefits: Reduces development time and cost for diagnostic tools, improves cross-vendor compatibility, and standardizes presentation of DTCs, parameters, and ECU functions.

Related Standards

- ISO 22900-2 / ISO 22900-3 (MVCI) - specifies the Modular Vehicle Communication Interface software requirements that ODX-modeled data are compatible with.

- Other ISO automotive diagnostics and vehicle communication standards may complement ODX for protocol-specific implementations.

Keywords: ISO 22901-1, ODX, Open Diagnostic Data Exchange, diagnostic data model, automotive diagnostics, ECU, MVCI, XML, UML, diagnostic trouble codes.

Buy Documents

ISO 22901-1:2008 - Road vehicles -- Open diagnostic data exchange (ODX)

ISO 22901-1:2008 - Road vehicles -- Open diagnostic data exchange (ODX)

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

TÜV Rheinland

TÜV Rheinland is a leading international provider of technical services.

TÜV SÜD

TÜV SÜD is a trusted partner of choice for safety, security and sustainability solutions.

AIAG (Automotive Industry Action Group)

American automotive industry standards and training.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO 22901-1:2008 is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Road vehicles — Open diagnostic data exchange (ODX) — Part 1: Data model specification". This standard covers: ISO 22901-1:2008 specifies the concept of using a new industry standard diagnostic format to make diagnostic data stream information available to diagnostic tool application manufacturers, in order to simplify the support of the aftermarket automotive service industry. The Open Diagnostic Data Exchange (ODX) modelled diagnostic data are compatible with the software requirements of the Modular Vehicle Communication Interface (MVCI), as specified in ISO 22900-2 and ISO 22900-3. The ODX modelled diagnostic data will enable an MVCI device to communicate with the vehicle Electronic Control Unit(s) (ECU) and interpret the diagnostic data contained in the messages exchanged between the external test equipment and the ECU(s). For ODX compliant external test equipment, no software programming is necessary to convert diagnostic data into technician readable information to be displayed by the tester. The ODX specification contains the data model to describe all diagnostic data of a vehicle and physical ECU, e.g. diagnostic trouble codes, data parameters, identification data, input/output parameters, ECU configuration (variant coding) data and communication parameters. ODX is described in Unified Modelling Language (UML) diagrams and the data exchange format uses Extensible Mark-up Language (XML). The ODX modelled diagnostic data describe: protocol specification for diagnostic communication of ECUs; communication parameters for different protocols and data link layers and for ECU software; ECU programming data (Flash); related vehicle interface description (connectors and pinout); functional description of diagnostic capabilities of a network of ECUs; ECU configuration data (variant coding). The purpose of ISO 22901-1:2008 is to ensure that diagnostic data from any vehicle manufacturer is independent of the testing hardware and protocol software supplied by any test equipment manufacturer.

ISO 22901-1:2008 specifies the concept of using a new industry standard diagnostic format to make diagnostic data stream information available to diagnostic tool application manufacturers, in order to simplify the support of the aftermarket automotive service industry. The Open Diagnostic Data Exchange (ODX) modelled diagnostic data are compatible with the software requirements of the Modular Vehicle Communication Interface (MVCI), as specified in ISO 22900-2 and ISO 22900-3. The ODX modelled diagnostic data will enable an MVCI device to communicate with the vehicle Electronic Control Unit(s) (ECU) and interpret the diagnostic data contained in the messages exchanged between the external test equipment and the ECU(s). For ODX compliant external test equipment, no software programming is necessary to convert diagnostic data into technician readable information to be displayed by the tester. The ODX specification contains the data model to describe all diagnostic data of a vehicle and physical ECU, e.g. diagnostic trouble codes, data parameters, identification data, input/output parameters, ECU configuration (variant coding) data and communication parameters. ODX is described in Unified Modelling Language (UML) diagrams and the data exchange format uses Extensible Mark-up Language (XML). The ODX modelled diagnostic data describe: protocol specification for diagnostic communication of ECUs; communication parameters for different protocols and data link layers and for ECU software; ECU programming data (Flash); related vehicle interface description (connectors and pinout); functional description of diagnostic capabilities of a network of ECUs; ECU configuration data (variant coding). The purpose of ISO 22901-1:2008 is to ensure that diagnostic data from any vehicle manufacturer is independent of the testing hardware and protocol software supplied by any test equipment manufacturer.

ISO 22901-1:2008 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 43.180 - Diagnostic, maintenance and test equipment. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO 22901-1:2008 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 22901-1

First edition

2008-11-15

Road vehicles — Open diagnostic data

exchange (ODX) —

Part 1:

Data model specification

Véhicules routiers — Échange de données de diagnostic ouvert

(ODX) —

Partie 1: Spécification de modèle de données

Reference number

©

ISO 2008

PDF disclaimer

PDF files may contain embedded typefaces. In accordance with Adobe's licensing policy, such files may be printed or viewed but shall

not be edited unless the typefaces which are embedded are licensed to and installed on the computer performing the editing. In

downloading a PDF file, parties accept therein the responsibility of not infringing Adobe's licensing policy. The ISO Central Secretariat

accepts no liability in this area.

Adobe is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated.

Details of the software products used to create the PDF file(s) constituting this document can be found in the General Info relative to

the file(s); the PDF-creation parameters were optimized for printing. Every care has been taken to ensure that the files are suitable for

use by ISO member bodies. In the unlikely event that a problem relating to them is found, please inform the Central Secretariat at the

address given below.

This CD-ROM contains the publication ISO 22901-1:2008 in portable document format (PDF), which can be

viewed using Adobe® Acrobat® Reader.

Adobe and Acrobat are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated.

© ISO 2008

All rights reserved. Unless required for installation or otherwise specified, no part of this CD-ROM may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from ISO. Requests for permission to reproduce this product

should be addressed to

ISO copyright office • Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20 • Switzerland

Internet c

...

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 22901-1

First edition

2008-11-15

Road vehicles — Open diagnostic data

exchange (ODX) —

Part 1:

Data model specification

Véhicules routiers — Échange de données de diagnostic ouvert

(ODX) —

Partie 1: Spécification de modèle de données

Reference number

©

ISO 2008

PDF disclaimer

This PDF file may contain embedded typefaces. In accordance with Adobe's licensing policy, this file may be printed or viewed but

shall not be edited unless the typefaces which are embedded are licensed to and installed on the computer performing the editing. In

downloading this file, parties accept therein the responsibility of not infringing Adobe's licensing policy. The ISO Central Secretariat

accepts no liability in this area.

Adobe is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated.

Details of the software products used to create this PDF file can be found in the General Info relative to the file; the PDF-creation

parameters were optimized for printing. Every care has been taken to ensure that the file is suitable for use by ISO member bodies. In

the unlikely event that a problem relating to it is found, please inform the Central Secretariat at the address given below.

© ISO 2008

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from either ISO at the address below or

ISO's member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

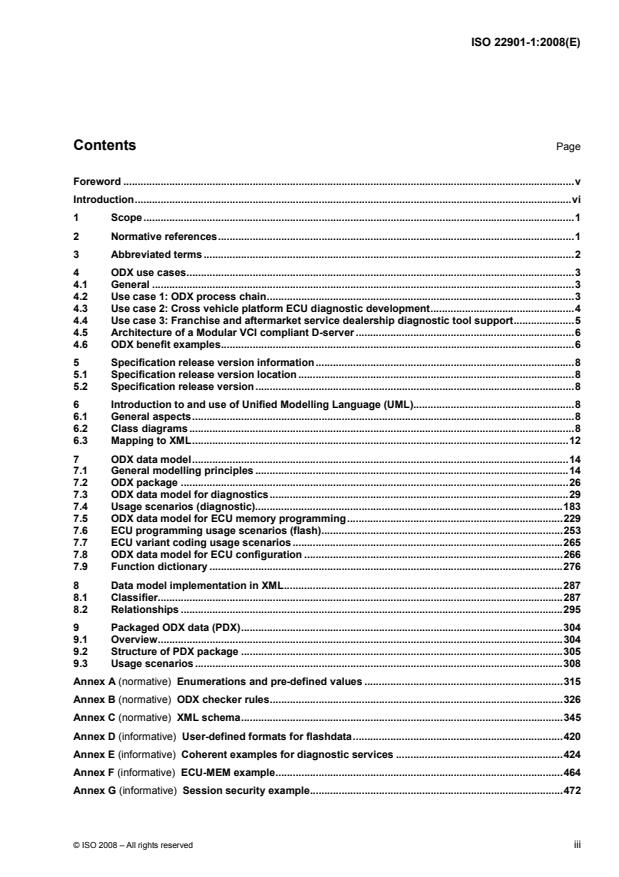

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction.vi

1 Scope.1

2 Normative references.1

3 Abbreviated terms .2

4 ODX use cases.3

4.1 General .3

4.2 Use case 1: ODX process chain.3

4.3 Use case 2: Cross vehicle platform ECU diagnostic development.4

4.4 Use case 3: Franchise and aftermarket service dealership diagnostic tool support.5

4.5 Architecture of a Modular VCI compliant D-server .6

4.6 ODX benefit examples.6

5 Specification release version information.8

5.1 Specification release version location .8

5.2 Specification release version.8

6 Introduction to and use of Unified Modelling Language (UML).8

6.1 General aspects.8

6.2 Class diagrams .8

6.3 Mapping to XML.12

7 ODX data model.14

7.1 General modelling principles .14

7.2 ODX package .26

7.3 ODX data model for diagnostics.29

7.4 Usage scenarios (diagnostic).183

7.5 ODX data model for ECU memory programming.229

7.6 ECU programming usage scenarios (flash).253

7.7 ECU variant coding usage scenarios .265

7.8 ODX data model for ECU configuration .266

7.9 Function dictionary .276

8 Data model implementation in XML.287

8.1 Classifier.287

8.2 Relationships .295

9 Packaged ODX data (PDX).304

9.1 Overview.304

9.2 Structure of PDX package .305

9.3 Usage scenarios .308

Annex A (normative) Enumerations and pre-defined values .315

Annex B (normative) ODX checker rules.326

Annex C (normative) XML schema.345

Annex D (informative) User-defined formats for flashdata.420

Annex E (informative) Coherent examples for diagnostic services .424

Annex F (informative) ECU-MEM example.464

Annex G (informative) Session security example.472

Bibliography .485

iv © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies

(ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through ISO

technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical committee has been

established has the right to be represented on that committee. International organizations, governmental and

non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work. ISO collaborates closely with the

International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of electrotechnical standardization.

International Standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

The main task of technical committees is to prepare International Standards. Draft International Standards

adopted by the technical committees are circulated to the member bodies for voting. Publication as an

International Standard requires approval by at least 75 % of the member bodies casting a vote.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of patent

rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

ISO 22901-1 was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 22, Road vehicles, Subcommittee SC 3,

Electrical and electronic equipment.

ISO 22901 consists of the following parts, under the general title Road vehicles — Open diagnostic data

exchange (ODX):

⎯ Part 1: Data model specification

The following parts are under preparation:

⎯ Part 2: Emissions-related diagnostic data

Introduction

The purpose of this part of ISO 22901 is to define the data format for transferring Electronic Control Unit

(ECU) diagnostic and programming data between the system supplier, vehicle manufacturer and service

dealerships and diagnostic tools of different vendors.

In today's automotive industry, an informal description is generally used to document the diagnostic data

stream information of vehicle ECUs. Any user wishing to use the ECU diagnostic data stream documentation

to set up development tools or service diagnostic test equipment needs a manual transformation of this

documentation into a format readable by these tools. This effort will no longer be required if the diagnostic

data stream information is provided in Open Diagnostic Data Exchange (ODX) format and if those tools

support the ODX format.

This part of ISO 22901 includes the data model definition of ECU diagnostic and programming data and the

related vehicle interface description in Unified Modelling Language (UML). This part of ISO 22901 also

includes an implementation by Extensible Mark-up Language (XML) schema in Annex C.

vi © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 22901-1:2008(E)

Road vehicles — Open diagnostic data exchange (ODX) —

Part 1:

Data model specification

1 Scope

This part of ISO 22901 specifies the concept of using a new industry standard diagnostic format to make

diagnostic data stream information available to diagnostic tool application manufacturers, in order to simplify

the support of the aftermarket automotive service industry. The Open Diagnostic Data Exchange (ODX)

modelled diagnostic data are compatible with the software requirements of the Modular Vehicle

Communication Interface (MVCI), as specified in ISO 22900-2 and ISO 22900-3. The ODX modelled

diagnostic data will enable an MVCI device to communicate with the vehicle Electronic Control Unit(s) (ECU)

and interpret the diagnostic data contained in the messages exchanged between the external test equipment

and the ECU(s). For ODX compliant external test equipment, no software programming is necessary to

convert diagnostic data into technician readable information to be displayed by the tester.

The ODX specification contains the data model to describe all diagnostic data of a vehicle and physical ECU,

e.g. diagnostic trouble codes, data parameters, identification data, input/output parameters, ECU configuration

(variant coding) data and communication parameters. ODX is described in Unified Modelling Language (UML)

diagrams and the data exchange format uses Extensible Mark-up Language (XML).

The ODX modelled diagnostic data describe:

⎯ protocol specification for diagnostic communication of ECUs;

⎯ communication parameters for different protocols and data link layers and for ECU software;

⎯ ECU programming data (Flash);

⎯ related vehicle interface description (connectors and pinout);

⎯ functional description of diagnostic capabilities of a network of ECUs;

⎯ ECU configuration data (variant coding).

Figure 1 shows the usage of ODX in the ECU life cycle.

The purpose of this part of ISO 22901 is to ensure that diagnostic data from any vehicle manufacturer is

independent of the testing hardware and protocol software supplied by any test equipment manufacturer.

2 Normative references

The following referenced documents are indispensable for the application of this document. For dated

references, only the edition cited applies. For undated references, the latest edition of the referenced

document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 8601, Data elements and interchange formats — Information interchange — Representation of dates and

times

ISO/IEC 8859-1, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 1: Latin

alphabet No. 1

ISO/IEC 8859-2, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 2: Latin

alphabet No. 2

ISO/IEC 10646, Information technology — Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS)

ISO 22900-2, Road vehicles — Modular vehicle communication interface (MVCI) — Part 2: Diagnostic

protocol data unit application programming interface (D-PDU API)

ISO 22900-3, Road vehicles — Modular vehicle communication interface (MVCI) — Part 3: Diagnostic server

application programming interface (D-Server API)

IEEE 754, Binary floating-point arithmetic

XML Schema — 2, XML Schema Part 2: Datatypes, 2nd Edition, W3C Recommendation, 2004-10-28

ASAM MCD 2, Harmonized Data Objects Version 1.0

3 Abbreviated terms

API Application Programming Interface

ASAM Association for Standardisation of Automation and Measuring Systems

ASCII American Standard for Character Information Interchange

DOP Data Object Property

ECU Electronic Control Unit

GMT Greenwich Mean Time

MCD Measurement, Calibration and Diagnosis

ODX Open Diagnostic Data Exchange

OEM Original Equipment Manufacturer

PDU Protocol Data Unit

PDX Packaged ODX

UML Unified Modelling Language

UTC Coordinated Universal Time

VMM Vehicle Message Matrix

W3C World Wide Web Consortium

XML Extensible Mark-up Language

2 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

4 ODX use cases

4.1 General

Figure 1 — Usage of ODX data in the ECU life cycle shows the usage of ODX in the ECU life cycle.

Engineering, manufacturing, and service specify communication protocol and data to be implemented in the

ECU. This information will be documented in a structured format utilizing the XML standard and by an

appropriate ODX authoring tool. There is potential to generate ECU software from the ODX file. Furthermore,

the same ODX file is used to setup the diagnostic engineering tools to verify proper communication with the

ECU and to perform functional verification and compliance testing. Once all quality goals are met, the ODX file

may be released to a diagnostic database. Diagnostic information is now available to manufacturing, service,

OEM franchised dealers, and aftermarket service outlets via Intranet and Internet.

Figure 1 — Usage of ODX data in the ECU life cycle

4.2 Use case 1: ODX process chain

Figure 2 shows an example of how ODX data is used in a process chain consisting of three phases, as

described below.

a) Phase A of the development process between vehicle manufacturer and system supplier comprises the

exchange of ODX data to support the development of the diagnostic implementation in the ECU and the

development tools.

b) In phase B of the development process at the vehicle manufacturer, the engineering departments release

the ODX data into a diagnostic database. The manufacturing and service departments use the ODX data

as the basis to setup the End-Of-Line test equipment and service application development tools and

generate service documentation.

c) Phase C of the development process supports the service dealership diagnostic and programming tools.

The service department develops service tool application software based on the ODX data model. The

diagnostic and programming software is now available to all service dealerships.

The ODX data is the base for all exchange of diagnostic and programming data.

Figure 2 — Example of ODX process chain

4.3 Use case 2: Cross vehicle platform ECU diagnostic development

A vehicle manufacturer implements electronic systems into multiple new vehicle platforms. There is little

variation in the electronic system across the different vehicle platforms. Utilizing the same ECU in many

different vehicle platforms reduces redundant development effort. The majority of design, normal operation,

and diagnostic data of an electronic system can be reused in various vehicles.

Large automotive manufacturer tend to have multiple engineering development centres. Diagnostic data

exchange can be based on the ODX data format to reduce the amount of proofreading of diagnostic data at

different development sites. Establishing an ODX compliant tool chain will avoid re-authoring diagnostic data

into various specific formats at different engineering sites.

4 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Figure 3 shows an example of cross vehicle platform ECU diagnostic development between two engineering

sites.

Figure 3 — Example of cross vehicle platform ECU diagnostic development

4.4 Use case 3: Franchise and aftermarket service dealership diagnostic tool support

Figure 4 shows one of many scenarios a vehicle manufacturer may implement to support the service

dealership, franchise and aftermarket. ODX files may be converted into an ODX runtime format for download

to the dealership diagnostic system.

IMPORTANT — The ODX runtime data format may be different between many diagnostic and

programming applications and tools. In such cases, an ODX runtime converter may be used to

support the data conversion to dealership specific test equipment.

Figure 4 — Example of automotive dealership diagnostic tool support

4.5 Architecture of a Modular VCI compliant D-server

Figure 5 shows the interfaces of a D-server and the position of ODX in a diagnostic system. The D-server may

use its own internal specific runtime data format. This data can be imported from the ODX using a specific

format converter.

Figure 5 — Architecture of a Modular VCI compliant D-server

4.6 ODX benefit examples

4.6.1 ECU system supplier

The following benefits are applicable to the ECU system supplier:

⎯ automatic configuration of ECU diagnostic data stream & protocol;

⎯ documentation is generated from XML data format (ECU diagnostic content = documentation);

⎯ automatic configuration of development tester to verify ECU diagnostic behaviour;

⎯ XML data format provides machine readable information to import into supplier diagnostic data base;

⎯ generation of source code to configure diagnostic kernel software components.

4.6.2 Vehicle manufacturer engineering

The following benefits are applicable to the vehicle manufacturer engineering:

⎯ reduction of diagnostic data stream authoring effort;

⎯ various development testers can be supported with “single source” data;

⎯ one single file format for import and export into/from diagnostic database.

6 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

4.6.3 Vehicle manufacturer production

The following benefits are applicable to the vehicle manufacturer production:

⎯ reduced effort for diagnostic data verification, because verification needs to be performed only once;

⎯ reuse of verified diagnostic data;

⎯ fewer errors because of fewer manual process steps;

⎯ end-of-line tester uses the same diagnostic data as engineering diagnostic tester.

4.6.4 Vehicle manufacturer service department and dealerships

The following benefits are applicable to the vehicle manufacturer service department and dealerships:

⎯ more convenient reuse of verified diagnostic data;

⎯ less cost to distribute diagnostic data;

⎯ “pull” (via Intranet/Internet) diagnostic data (e.g. from a portal into a D-server) versus “push” (e.g. send

CD ROMs);

⎯ one single file format for various diagnostic service systems.

4.6.5 Test equipment manufacturer

The following benefits are applicable to the test equipment manufacturer:

⎯ less effort needed to implement high quality scan tool software by using a generic data driven approach;

⎯ focus on “rich diagnostic application(s)” versus bits & bytes;

⎯ more convenient reuse of vehicle manufacturer verified diagnostic data.

4.6.6 Franchise and aftermarket dealerships

The following benefits are applicable to the franchise and aftermarket dealerships:

⎯ more convenient reuse of vehicle manufacturer verified diagnostic data;

⎯ tester configuration by data download instead of by software modification;

⎯ download on demand versus buying tester software update upfront.

4.6.7 Legal authorities

The following benefits are applicable to the legal authorities:

⎯ standardized description format for enhanced diagnostic data documentation (e.g. DTCs, PIDs);

⎯ enables road-side scan tools and I&M (inspection and maintenance) tools to be vehicle manufacturer

independent;

⎯ fulfils requirement of making enhanced diagnostic data available to independent aftermarket.

5 Specification release version information

5.1 Specification release version location

The release version of the ODX standard can be obtained from every ODX file instance. It is contained in the

MODEL-VERSION element.

VERSION="2.2.0">

5.2 Specification release version

The specification release version of this part of ISO 22901 is: 2.2.0.

6 Introduction to and use of Unified Modelling Language (UML)

6.1 General aspects

Unified Modelling Language (UML) is used to define the ODX data model formally and unambiguously. It

enhances readability by graphical data model diagrams.

A short introduction to UML is given in this clause. Only those aspects of UML are described that are used in

the ODX data model. Specifically, from the large set of available UML diagrams, class diagrams are only

applied for data modelling.

6.2 Class diagrams

6.2.1 Class

The central modelling element in UML is a class. A class represents a set of similar objects. Generally

speaking, a class can be instantiated many times. Every instance of a class is called an object. A class has

attributes (defining the properties of these objects) and methods (defining the actions an object can perform).

For ODX, methods are irrelevant and are not used.

Figure 6 — UML representation of class

Figure 6 shows the representation of a class and its attributes in UML notation. A class is symbolized by a

rectangle having up to three fields. The top field contains the name of the class, e.g. PERSON. The second

field contains the attributes of the class, e.g. NAME, AGE, PROFESSION, and ID. Methods are defined in an

optional third field. The attribute field is not always displayed in the ODX data model diagrams. Since the

method-field is unused in the ODX data model, it is never displayed.

Attributes consist of the attribute name, e.g. NAME, followed by the attribute’s cardinality, e.g. [1] or [0.1] and

the attribute type, e.g. String. Furthermore, a default value for the attribute may be specified. Such a default

value follows the type descriptor of the attribute and is separated from it by the symbol “=”.

8 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

UML attributes specified with the <> stereotype in front of their name are implemented as XML attributes

of XML elements. UML attributes without this stereotype are implement as XML sub-elements of XML

elements.

Throughout the ODX data model, class names and attribute names are written in capital letters.

6.2.2 Inheritance relationships

Classes can inherit attributes from other classes. In Figure 7, a new class SCHOOLKID is derived from the

class PERSON. This means that implicitly the class SCHOOLKID has all the same attributes as PERSON

plus those that are defined specifically for the new class SCHOOLKID, e.g. GRADE. PERSON is called the

parent or super class; SCHOOLKID is called the child or subclass of the inheritance relationship. Because the

subclass adds more detail to the super class and is thus more specific, inheritance relationships are often

called “specializations”.

Inheritance relationships can be used to build inheritance trees of arbitrary depth. A class in such a tree

inherits all attributes from those classes in the transitive closure of all ancestors (parents, grandparents, etc.)

in the inheritance tree.

Figure 7 — UML representation of inheritance relationship

6.2.3 Aggregation and composition relationships

Besides the inheritance relationship, a pair of classes may also have an aggregation or a composition

relationship. Aggregation or composition relationships are used if an object of one class is contained in an

object of another class. They are drawn as a line with a diamond at the end of the containing class. A

composition relationship’s diamond is filled; an aggregation’s diamond is not.

The difference between these two kinds of relationships is as follows:

a) the contained element in a composition relationship is a part of the containing element;

b) if the containing element is deleted, the contained element no longer exists.

Therefore, composition means an object may only be contained in one other object. An aggregation

relationship is one of shared objects. This means that multiple objects may aggregate the same object.

1)

Consequently, an aggregated object still exists, even if the aggregating object is deleted .

1) In the special case where the data model is implemented in XML (see below), aggregation and composition

relationships are both mapped onto a sub element relationship between the two model elements. However, the UML

semantics guide prohibits multiple classes from having a composition relationship to the same class. Therefore,

aggregation relationships are used instead, even though the implementation in XML does not differ.

Figure 8 gives an example of three classes with composition and aggregation relationships defined. A

PERSON may have two feet (two objects of type FOOT). A foot is generally an integral part of its owner.

Therefore, a composition relationship is used. If the PERSON no longer exists, nor do the feet. By contrast, a

PERSON may also have a lot of COATs. However, a COAT may generally be used by multiple PERSONs

and its life-cycle is generally independent of the life-cycle of its wearers. Consequently, the relationship

between a PERSON and a COAT is modelled as an aggregation relationship.

Composition relationships may carry cardinalities, as shown in Figure 8. The following cardinalities are

common in UML:

⎯ 1 exactly one (mandatory);

⎯ 0.1 zero or one (optional);

⎯ 1.* one or more;

⎯ 0.* or * zero or more.

More specific cardinalities may be specified, e.g. 5 or 2.8.

Cardinalities are read as follows: To specify how many objects of class PERSON are related to one object of

class FOOT, the cardinality at the PERSON end of the relationship is use. Vice versa the cardinality at the

FOOT end of the relationship is used. This yields the following result: one object of class FOOT may be

related to exactly one object of class PERSON (a foot always belongs to one and only one person) and one

object of class PERSON shall be related to exactly two objects of class FOOT (a person usually has two feet).

Figure 8 — UML representation of composition and aggregation relationships

6.2.4 Association relationships

The third kind of class relationship used within the ODX data model is the association relationship. It is drawn

as a simple line between two classes. An association relationship has weaker semantics than the composition

relationship. Here, both objects have “equal rights”. An association relationship opens visibility onto the

attributes of the related objects. Figure 9 gives an example of an association. In an association, objects of one

class may be related to one or more objects of the other class. To restrict the number of associations of the

same type between two classes, cardinalities are used in the same way as for compositions.

10 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Figure 9 — UML representation of association relationship

Associations may carry a name and a role name can be given at every association end. In Figure 9, the

PERSON class carries the role MOTHER in a relationship to a SCHOOLKID. The cardinalities state that a

SCHOOLKID has exactly one mother, whereas a PERSON may be MOTHER or an arbitrary number of

SCHOOLKIDs.

An association relationship may carry an arrow at one association end. This makes it possible to specify which

of the objects may actually access attributes of the other.

6.2.5 Association classes

An association class is a hybrid of an association and a class. Generally speaking, it can be interpreted as an

association carrying its own attributes (and methods). It is drawn like an association with a class symbol being

connected to the centre of the association line with a dashed line (see Figure 10).

The example of a PERSON being employed by an EMPLOYER is modelled as an association class in

Figure 10. Here, the employment relationship has an attribute named SALARY. This employment-specific

salary is clearly not a property of a PERSON, because one person may have multiple salaries. In addition, the

salary may not exist, if the PERSON is unemployed. It is also not a property of the EMPLOYER, because the

EMPLOYER has many different employee-specific salaries. This is the best indication that the SALARY is a

property of an employment relationship.

Figure 10 — UML representation of association class

6.2.6 Interfaces

An interface makes certain properties of an object available to other objects.

Interfaces are a special means to group certain aspects of a class and make other classes dependent on only

one of these aspects, instead of the class as a whole.

An interface symbol looks identical to a class symbol. It can be distinguished from class through the

stereotype <> within the symbol’s name field.

Figure 11 contains a small example of how interfaces are used within a model. A class COMPANY

implements two interfaces: EMPLOYEE and COMPETITOR. A person being employed by the company will

not observe the company as a competitor and a competing company will not observe the competitor as an

employer. If a class implements an interface, this is shown by a dashed arrow, similar to the inheritance arrow.

A tester class of an interface (e.g. PERSON) may simply use associations or aggregations to relate to an

interface. It is important to know that the tester class (PERSON) may only use those aspects of a class

implementing the EMPLOYER interface that are defined within this interface. Therefore, a company also may

equally employ a person by an administrative body, because the latter also implements the interface

EMPLOYEE.

Figure 11 — UML representation of interfaces

6.2.7 Constraints

The UML makes it possible to define constraints on the model elements used. One constraint that is used

frequently is the {xor} constraint between two associations (or aggregations). It enforces that an instance of

one class has a relationship with instances of one or the other associated class, but never both at the same

time.

Figure 12 displays an example of such a constraint. A person wears either two SHOEs or two BOOTs at any

one time, but never both together.

Figure 12 — UML representation of constraint

6.3 Mapping to XML

The target implementation format of the ODX exchange format is XML. This subclause explains briefly how

the UML model is mapped onto XML language elements. It is not comprehensive, but rather serves as an

example to simplify comprehension of the XML examples given throughout this part of ISO 22901. The

complete XML mapping rules and the resulting XML schema are described in Clause 8.

12 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

Generally speaking, the rules below apply.

a) A class is generally mapped onto an XML element.

b) Attributes of a class are mapped onto XML attributes of the XML element if the <> stereotype is

defined for the UML attribute, or onto a XML sub element if no stereotype is defined. If an UML attribute

with stereotype <> is defined, the attribute is simply mapped onto the content of the XML

element.

c) Classes connected to another class via a composition or aggregation relationship are mapped onto sub

elements. In cases where the target cardinality of the contained class is multiple, a wrapper element

around the sub elements is generated. The wrapper element is omitted if the {nowrapper}-constraint is

defined on the composition or aggregation relationship respectively.

d) Associations to other classes are mapped onto XML references to other elements. Three kinds of

reference mechanisms have been defined for ODX: these are marked through stereotypes <>,

<> and <>, respectively. For the detailed implementation of these reference

mechanisms, see 7.3.13.

e) In ODX, classes that are part of an inheritance hierarchy are mapped in XML, depending on which UML

inheritance relationship stereotype is used. The two inheritance stereotypes used in ODX are <

child>> and <>. Both stereotypes represent specializations, as defined in 6.2.2. When

specifying an inheritance relationship using the <> stereotype, all child or sub-types are

implemented in XML; i.e. every child type will have one XML schema type. When using the <

parent>> stereotype, the generated XML element carries an attribute of name xsi:type. It contains the

name of the child-type that is used in the particular instance.

Figure 13 — UML representation of mapping example

In accordance with these rules, the example in Figure 13 is mapped onto the XML document shown below.

The root element has been included to satisfy shapeliness of the XML.

Jack O. Trades

All Duty Service Technician

Gucci

Kevin

Throughout this part of ISO 22901, some other constraints and stereotypes are used that have not been

explained within this subclause. These include the following:

⎯ <> for inheritance between diagnostic layers;

⎯ <> to deviate from the standard naming schema that XML elements are named like their

UML class counterparts;

⎯ <> to describe the import of data from another diagnostic layer;

⎯ {ordered} to enforce that the order of XML sub elements is significant and shall not be changed by any

ODX-compliant tool;

For more detailed information on the mapping to XML, see Clause 8.

7 ODX data model

7.1 General modelling principles

7.1.1 Common members

SHORT-NAME identifies an ODX object. Its length is limited to 128 characters. A short name consists of

letters, digits and “_” character. The following regular expression describes the syntax of short names:

[a-zA-Z0-9_]+

LONG-NAME is a short description of the functionality of the ODX object. Its length is limited to 255

characters. The LONG-NAME should be displayed in human interface of an application instead of SHORT-

NAME.

DESC describes detailed the functionality of the ODX object and has no length restriction. This element is

optional and may involve several paragraphs marked by the ordered list of element

. The following tags

known from HTML can be used to format the text:

, , , , , ,

- ,

- .

LONG-NAME and DESC may also have an optional member TI (text identifier) that supports multilingualism

for different kinds of text module. The mapping technology is tool-/manufacturer-specific. For example, they

may occur in an external file. The TI attribute then allows the mapping between external and internal

descriptions and can be used for language translations.

ELEMENT-ID is used as a common type to represent the above listed members throughout the ODX data

model. An attribute HANDLE of this type is used at all elements using these common members.

ID is an identifier used by the linking concept “odxlink” described later in this part of ISO 22901. The value of

ID is restricted by XML specification. No ODX compliant tool shall change the content of the ID over the whole

life cycle of the data element. No system that provides import/export facilities of ODX may change existing IDs

during import/modify/export cycles without explicit command by a user. Every ID needs to be unique in one

coherent ODX data pool (project). The process owner may explicitly decide to change IDs and use a tool to

perform the changes, i.e. the tool can assign a new ID to a new object. The process owner decides upon the

method used to ensure uniqueness of IDs, so as to avoid the necessity of subsequent changes due to

14 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

conflicts. However, the use of Universally Unique Identifiers (UUIDs) as described in ISO/IEC 11578 is

recommended.

OID is used for invariant identification of an object, but not for linking. Any ODX compliant tool shall not

change the content of the Object-ID (if present) over the whole life cycle of the data element. Any system that

provides import/export facilities of ODX into an internal format shall ensure the OIDs are maintained during an

import/modify/export cycle. The process owner is responsible for ensuring the uniqueness of the OID

throughout the overall process chain. The use of Universally Unique Identifiers (UUIDs) as described in

ISO/IEC 11578 is recommended.

7.1.2 Common objects

7.1.2.1 Special data group

Special data groups (SDGs) are the standard extension mechanism of ODX, and are used to store any kind of

data that is not covered by the standardized part of the data model in a structured way. Examples for the use

of SDGs in ODX are the company-specific documentation in COMPANY-DOC-INFO. The ODX specification

defines the structure of SDGs, but not its content; thus a standard diagnostic tool conforming to ODX is not

required to process SDGs.

Figure 14 — UML representation of special data group (SDG) illustrates the modelling in UML.

Figure 14 — UML representation of special data group (SDG)

An SDG contains an optional SDG-CAPTION to describe the SDG content, and a list of SDG and SD objects

that contain the special data. This list can contain an arbitrary number of SDGs and SDs, and the ordering of

these SDGs and SDs is not restricted in any way. SDGs can be nested recursively; that way, very complex

data structures may be defined as SDGs. The member SI is used to add semantic information to the

appropriate object, e.g. it can be used to implement a table with key-value pairs (see example 1 below). The

reuse of an already defined SDG-CAPTION can be done with the SDG-CAPTION-REF, which results from the

odxlink between SDG and SDG-CAPTION.

EXAMPLE 1 Definition of tables of property lists with SDGs:

properties

A table of key-value pairs

4711

007

1234567

EXAMPLE 2 Describing deep substructures with SDGs (fictitious example).

With SDGs, it is possible to create complex structures of any depth, e.g. Figure 15 — Special data group

shows a number of tables, which can be combined to build a 3-dimensional matrix.

Figure 15 — Special data group

This matrix can be described by an SDG structure of depth 3:

matrix

A 3-dimensional matrix mapped to an SDG structure

firstTable

firstRow

L111

L112

secondRow

L121

L122

16 © ISO 2008 – All rights reserved

secondTable

firstRow

L211

L212

secondRow

L221

L222

7.1.2.2 AUDIENCE and ADDITIONAL-AUDIENCE

Audiences define the target group or groups of users for the following elements:

⎯ DIAG-COMM;

⎯ MULT

...

- ,

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...