ISO 24617-1:2012

(Main)Language resource management — Semantic annotation framework (SemAF) — Part 1: Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Language resource management — Semantic annotation framework (SemAF) — Part 1: Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Temporal information in natural language texts is an increasingly important component to the understanding of those texts. ISO 24617-1:2012, SemAF-Time, specifies a formalized XML-based markup language called ISO-TimeML, with a systematic way to extract and represent temporal information, as well as to facilitate the exchange of temporal information, both between operational language processing systems and between different temporal representation schemes. The use of guidelines for temporal annotation has been fully attested with examples from the TimeBank corpus, a collection of 183 documents that have been annotated by TimeML before the current version of ISO-TimeML was formulated.

Gestion des ressources langagières — Cadre d'annotation sémantique (SemAF) — Partie 1: Temps et événements (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Upravljanje z jezikovnimi viri - Ogrodje za semantično označevanje (SemAF) - 1. del: Čas in dogodki (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Časovne informacije v besedilih v naravnem jeziku so vedno pomembnejše za razumevanje teh besedil. Ta del standarda ISO 24617, SemAF-Time, določa formaliziran jezik za označevanje ISO-TimeML, ki temelji na XML in na sistematičen način izlušči in predstavi časovne informacije ter olajšuje izmenjavo časovnih informacij med sistemi obdelave izvajalnega jezika in med različnimi shemami časovne predstavitve. Uporaba smernic za časovno označevanje je potrjena s primeri iz korpusa TimeBank, zbirko 183 dokumentov, ki so bili označeni s TimeML pred oblikovanjem trenutne različice ISO-TimeML.

General Information

- Status

- Published

- Publication Date

- 15-Jan-2012

- Technical Committee

- ISO/TC 37/SC 4 - Language resource management

- Drafting Committee

- ISO/TC 37/SC 4/WG 2 - Semantic annotation

- Current Stage

- 9093 - International Standard confirmed

- Start Date

- 16-Jun-2023

- Completion Date

- 12-Feb-2026

Overview

ISO 24617-1:2012 - SemAF‑Time (ISO‑TimeML) defines a standardized, XML‑based semantic annotation framework for representing temporal information (times and events) in natural language texts. The standard specifies an abstract metamodel and a concrete XML syntax (ISO‑TimeML) to extract, encode and exchange temporal expressions, events and temporal relations between them. The specification is grounded in existing practice (e.g., the TimeBank corpus of 183 TimeML‑annotated documents) and supports interoperable temporal annotation across language processing tools.

Key technical topics and requirements

- ISO‑TimeML concrete syntax: a formal XML representation for tagging temporal expressions and events, designed for stand‑off annotation and machine interoperability.

- Core elements:

<EVENT>,<TIMEX3>,<SIGNAL>for marking events, time expressions and temporal signals. - Link elements:

<TLINK>,<SLINK>,<ALINK>,<MLINK>for encoding temporal, subordinating, aspectual and modal relations between annotated items. - Attributes and metadata: tags for certainty, confidence and linguistic features (tense, aspect, polarity) to support richer semantic interpretation.

- Semantics: interval‑based and event‑based semantic models, handling tense, aspect and formal temporal relations to enable reasoning about ordering and duration.

- Normative and informative annexes: core annotation guidelines, fully annotated examples (including Chinese, Italian, Korean), tool references (ALEMBIC, CALLISTO, TANGO, TARSQI, IBM TimeML annotator) and a formal specification of attribute classes and elements.

Practical applications and who uses it

ISO 24617-1 is targeted at professionals and projects that need reliable, interoperable temporal annotation:

- NLP researchers and computational linguists developing temporal relation extraction, timeline construction and event ordering systems.

- Annotation teams and corpus developers creating training data (TimeBank‑style corpora) for machine learning and evaluation.

- Software developers and tool integrators implementing temporal parsers, knowledge extraction pipelines or question‑answering engines that require standard temporal markup.

- Enterprises in domains such as news analytics, legal and clinical text mining, historical research and any application needing precise event-time interpretation.

Benefits include consistent annotations across tools, improved temporal reasoning, and simpler data exchange between systems using the ISO‑TimeML format.

Related standards and keywords

- Part of the ISO Semantic Annotation Framework (SemAF) series.

- Relevant keywords: ISO 24617-1, SemAF-Time, ISO‑TimeML, TimeML, temporal annotation, temporal relations, TIMEX3, EVENT, TLINK, NLP, TimeBank, XML-based markup.

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO 24617-1:2012 is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Language resource management — Semantic annotation framework (SemAF) — Part 1: Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)". This standard covers: Temporal information in natural language texts is an increasingly important component to the understanding of those texts. ISO 24617-1:2012, SemAF-Time, specifies a formalized XML-based markup language called ISO-TimeML, with a systematic way to extract and represent temporal information, as well as to facilitate the exchange of temporal information, both between operational language processing systems and between different temporal representation schemes. The use of guidelines for temporal annotation has been fully attested with examples from the TimeBank corpus, a collection of 183 documents that have been annotated by TimeML before the current version of ISO-TimeML was formulated.

Temporal information in natural language texts is an increasingly important component to the understanding of those texts. ISO 24617-1:2012, SemAF-Time, specifies a formalized XML-based markup language called ISO-TimeML, with a systematic way to extract and represent temporal information, as well as to facilitate the exchange of temporal information, both between operational language processing systems and between different temporal representation schemes. The use of guidelines for temporal annotation has been fully attested with examples from the TimeBank corpus, a collection of 183 documents that have been annotated by TimeML before the current version of ISO-TimeML was formulated.

ISO 24617-1:2012 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 01.020 - Terminology (principles and coordination). The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO 24617-1:2012 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

SLOVENSKI STANDARD

01-julij-2013

Upravljanje z jezikovnimi viri - Ogrodje za semantično označevanje (SemAF) - 1.

del: Čas in dogodki (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Language resource management -- Semantic annotation framework (SemAF) -- Part 1:

Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Gestion des ressources langagières -- Cadre d'annotation sémantique (SemAF) -- Partie

1: Temps et événements (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Ta slovenski standard je istoveten z: ISO 24617-1:2012

ICS:

01.020 Terminologija (načela in Terminology (principles and

koordinacija) coordination)

01.140.20 Informacijske vede Information sciences

35.240.30 Uporabniške rešitve IT v IT applications in information,

informatiki, dokumentiranju in documentation and

založništvu publishing

2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno.

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 24617-1

First edition

2012-01-15

Language resource management —

Semantic annotation framework

(SemAF) —

Part 1:

Time and events (SemAF-Time,

ISO-TimeML)

Gestion des ressources langagières — Cadre d'annotation sémantique

(SemAF) —

Partie 1: Temps et événements (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Reference number

©

ISO 2012

© ISO 2012

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from either ISO at the address below or

ISO's member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

Contents Page

Foreword . vi

Introduction . vii

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Overview . 4

5 Motivation and requirements . 4

6 Basic concepts and metamodel . 5

7 Specification of ISO-TimeML . 8

7.1 Overview . 8

7.2 Abstract syntax . 8

7.2.1 Introduction . 8

7.2.2 Conceptual inventory . 9

7.2.3 Syntax rules . 9

7.3 Concrete XML-based syntax . 10

7.3.1 TimeML vs. ISO-TimeML: Stand-off annotation and other differences . 10

7.3.2 Naming conventions . 12

7.3.3 Example annotations . 12

7.3.4 Basic elements: , , and . 12

7.3.5 Link elements: , , and . 18

7.3.6 Other tags: , and . 22

8 Towards a semantics for ISO-TimeML . 26

8.1 Overview . 26

8.2 Tense and aspect in language . 26

8.2.1 Tense . 26

8.2.2 Aspect . 26

8.3 Temporal relations . 27

8.4 An interval-based semantics for ISO-TimeML . 28

8.4.1 Technical preliminaries for interval temporal logic . 28

8.4.2 Basic event-structure . 29

8.4.3 The interpretation of . 31

8.4.4 Interpretive rule summary . 36

8.5 An event-based semantics for ISO-TimeML . 37

8.5.1 Introduction . 37

8.5.2 Defining an event-based semantics . 38

Annex A (normative) Core annotation guidelines . 41

A.1 Introduction . 41

A.2 ISO-TimeML elements and their attributes . 41

A.2.1 The element . 41

A.2.2 The element . 48

A.2.3 The element . 55

A.3 The link elements: , , and . 56

A.3.1 Overview . 56

A.3.2 The element . 56

A.3.3 The element . 59

A.3.4 The element . 61

A.3.5 The element . 62

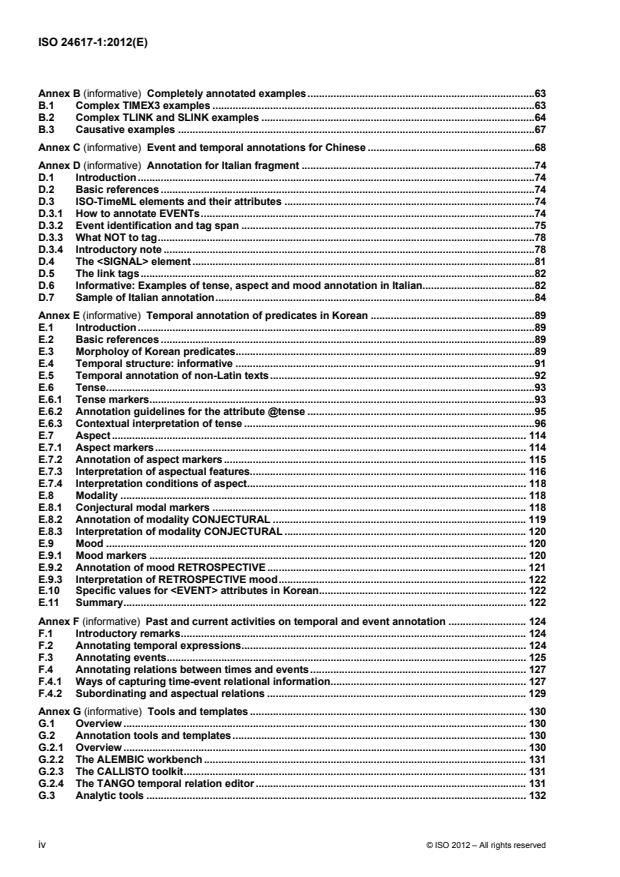

Annex B (informative) Completely annotated examples .63

B.1 Complex TIMEX3 examples .63

B.2 Complex TLINK and SLINK examples .64

B.3 Causative examples .67

Annex C (informative) Event and temporal annotations for Chinese .68

Annex D (informative) Annotation for Italian fragment .74

D.1 Introduction .74

D.2 Basic references .74

D.3 ISO-TimeML elements and their attributes .74

D.3.1 How to annotate EVENTs .74

D.3.2 Event identification and tag span .75

D.3.3 What NOT to tag .78

D.3.4 Introductory note .78

D.4 The element .81

D.5 The link tags .82

D.6 Informative: Examples of tense, aspect and mood annotation in Italian.82

D.7 Sample of Italian annotation .84

Annex E (informative) Temporal annotation of predicates in Korean .89

E.1 Introduction .89

E.2 Basic references .89

E.3 Morpholoy of Korean predicates .89

E.4 Temporal structure: informative .91

E.5 Temporal annotation of non-Latin texts .92

E.6 Tense .93

E.6.1 Tense markers .93

E.6.2 Annotation guidelines for the attribute @tense .95

E.6.3 Contextual interpretation of tense .96

E.7 Aspect . 114

E.7.1 Aspect markers . 114

E.7.2 Annotation of aspect markers . 115

E.7.3 Interpretation of aspectual features. 116

E.7.4 Interpretation conditions of aspect . 118

E.8 Modality . 118

E.8.1 Conjectural modal markers . 118

E.8.2 Annotation of modality CONJECTURAL . 119

E.8.3 Interpretation of modality CONJECTURAL . 120

E.9 Mood . 120

E.9.1 Mood markers . 120

E.9.2 Annotation of mood RETROSPECTIVE . 121

E.9.3 Interpretation of RETROSPECTIVE mood . 122

E.10 Specific values for attributes in Korean . 122

E.11 Summary . 122

Annex F (informative) Past and current activities on temporal and event annotation . 124

F.1 Introductory remarks . 124

F.2 Annotating temporal expressions . 124

F.3 Annotating events . 125

F.4 Annotating relations between times and events . 127

F.4.1 Ways of capturing time-event relational information . 127

F.4.2 Subordinating and aspectual relations . 129

Annex G (informative) Tools and templates . 130

G.1 Overview . 130

G.2 Annotation tools and templates . 130

G.2.1 Overview . 130

G.2.2 The ALEMBIC workbench . 131

G.2.3 The CALLISTO toolkit . 131

G.2.4 The TANGO temporal relation editor . 131

G.3 Analytic tools . 132

iv © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

G.3.1 Overview . 132

G.3.2 The TARSQI toolkit . 132

G.3.3 The IBM TimeML annotator . 133

G.3.4 The Amsterdam temporal component extractor . 133

G.3.5 The Time Calculus analyser . 133

Annex H (normative) Specification . 134

H.1 Requirement . 134

H.2 Attribute classes . 134

H.2.1 att.anchored . 134

H.2.2 att.annotate . 135

H.2.3 att.id . 135

H.2.4 att.lang . 135

H.2.5 att.linguistic . 136

H.2.6 att.pointing . 138

H.2.7 att.typed . 138

H.3 Elements . 139

H.3.1 . 139

H.3.2 . 139

H.3.3 . 140

H.3.4 . 141

H.3.5 . 141

H.3.6 . 142

H.3.7 . 143

H.3.8 . 145

H.3.9

H.3.10 . 146

H.3.11

H.3.12 . 146

Bibliography . 147

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies

(ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through ISO

technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical committee has been

established has the right to be represented on that committee. International organizations, governmental and

non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work. ISO collaborates closely with the

International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of electrotechnical standardization.

International Standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

The main task of technical committees is to prepare International Standards. Draft International Standards

adopted by the technical committees are circulated to the member bodies for voting. Publication as an

International Standard requires approval by at least 75 % of the member bodies casting a vote.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of patent

rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

ISO 24617-1 was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 37, Terminology and other language and content

resources, Subcommittee SC 4, Language resource management.

ISO 24617 consists of the following parts, under the general title Language resource management —

Semantic annotation framework (SemAF):

Part 1: Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Part 2: Dialogue acts

The following parts are under preparation:

Part 4: Semantic roles (SemAF-SRL)

Part 5: Discourse structure (SemAF-DS)

The following parts are planned:

Part 3: Named entities (SemAF-NE)

Part 6: Principles of semantic annotation

Part 7: Spatial information (ISO-Space)

Part 8: Relations in Discourse (SemAF-DRel)

vi © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

Introduction

This part of ISO 24617 results from the agreement between the TimeML Working Group and the ISO Working

Group, ISO/TC 37/SC 4/WG 2, Language resource management – Semantic annotation, that a joint activity

should take place to accommodate the two existing documents for annotating temporal information,

TimeML 1.2.1 and TimeML Annotation Guidelines, into ISO international standards. This work should lead to

the achievement of two objectives:

modification of the two documents in conformance to the ISO International Standards;

verification of the annotation guidelines for a wide coverage of multilingual resources.

It should be noted that this part of ISO 24617 provides normative guidelines not just for temporal information,

but also for information content in various types of events in English as well as other languages.

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 24617-1:2012(E)

Language resource management — Semantic annotation

framework (SemAF) —

Part 1:

Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

1 Scope

Temporal information in natural language texts is an increasingly important component to the understanding of

those texts. This part of ISO 24617, SemAF-Time, specifies a formalized XML-based markup language called

ISO-TimeML, with a systematic way to extract and represent temporal information, as well as to facilitate the

exchange of temporal information, both between operational language processing systems and between

different temporal representation schemes. The use of guidelines for temporal annotation has been fully

attested with examples from the TimeBank corpus, a collection of 183 documents that have been annotated

by TimeML before the current version of ISO-TimeML was formulated.

NOTE Throughout this document, SemAF-Time refers to the ISO 24617-1, while ISO-TimeML refers to the

annotation language specified in this document.

2 Normative references

The following referenced documents are indispensable for the application of this document. For dated

references, only the edition cited applies. For undated references, the latest edition of the referenced

document (including any amendments) applies.

NOTE The first reference shows how dates and times are represented and the second provides a format for the

standoff representation of ISO-TimeML annotation presented here.

ISO 8601:2004, Data elements and interchange formats — Information interchange — Representation of

dates and times

ISO 24612:2011, Language resource management — Linguistic annotation framework (LAF)

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions in ISO 8601:2004 and the following apply.

NOTE The terms and definitions provided below are provided to clarify the terminology relating to the metamodel,

specification, and semantics of ISO-TimeML. Terminology derived from XML and other formal languages as well as from

general temporal logics is not defined here.

3.1

ALINK

linking tag that represents a phase relation between an aspectual verb (or morpheme) and a predicate

denoting an event (3.5)

3.2

annotation

process of adding information to segments of language data or that information itself

3.3

beginning

instant (3.6) at which a temporal interval (3.17) begins

NOTE Adapted from Hobbs and Pan (2004).

3.4

end

instant (3.6) at which a temporal interval (3.17) ends

NOTE Adapted from Hobbs and Pan (2004).

3.5

event

eventuality

something that can be said to obtain or hold true, to happen or to occur

NOTE The term “event” is used here with a very broad notion of event, which includes all kinds of actions, states,

processes, etc. It is not to be confused with the more narrow notion of event as something that happens at a certain point

in time (such as the clock striking 2, or waking up) or during a short period of time (such as laughing).

3.6

instant

point in time with no interior points

NOTE Time is often viewed as a straight line from minus infinity to plus infinity. In this view, time is formed by an

infinite sequence of points. An instant can also be seen as an infinitesimally small interval. Cf. OWL-Time Ontology for

“instant”: http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-time/.

3.7

markable

entity in general, or segment of a text in particular, that is subject to an annotation (3.2)

3.8

MLINK

linking tag that represents the measurement of the duration of an event (3.5) or the measurement of the

length of a (possibly discontinuous) time span

3.9

point of event

instant (3.6) at which the event (3.5) mentioned in a given utterance occurs

NOTE Next to a point of speech, a point of event also needs to be defined in order to interpret tense. For example, in

“Arthur smiled”, the temporal location of the point of event can be defined as being prior to the point of speech.

3.10

point of reference

instant (3.6) of temporal perspective on the event (3.5) in a given utterance

NOTE 1 “Arthur will have gone by tomorrow”, where the point of speech is now, the point of event is some time in the

future, but before the point of reference referred to by “tomorrow”.

NOTE 2 To locate certain tenses in time, a third anchor point is also required, defined as the point of reference.

3.11

point of speech

time unit (3.17) at which a given utterance occurs

NOTE 1 The notion of point of speech is needed in order to interpret tense. This requires the use of anchor points in

time, of which the point of speech is one (point of text, see 3.12, is another one). For example, in “Arthur smiled”, the point

of speech is the time that the utterance is made.

NOTE 2 For a document as a whole, this may be considered to be the same as the document creation time.

2 © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

3.12

point of text

instant (3.6) at which reported speech is anchored

NOTE It is the point of time considered in the text of the speech. So for example, when a person is telling a story, it is

not enough to know the point of the speech itself (the document creation time), but the point at which the speech in the

story is taking place.

3.13

representation

format in which an annotation (3.2) is rendered, for instance in XML, independent of its content

3.14

SLINK

linking tag that represents a subordinating relation between two events (3.5)

3.15

temporal interval

period

uninterrupted stretch of time, with internal point structure.

NOTE 1 Adapted from WordNet.

NOTE 2 Time is often viewed as a straight line from minus infinity to plus infinity. A temporal interval is a part of that

line without any holes, containing all the points between its beginning and its end.

NOTE 3 In mathematics, an important issue is whether an interval includes its beginning and its end (is “closed”) or not

(is “open” or “half-open”). In natural language descriptions of intervals this may also be relevant, as when describing an

interval in terms of a number of days, but not with the same granularity as in mathematics. Cf. OWL-Time Ontology for

“interval”: http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-time/.

3.16

temporal ordering relation

relation that determines how objects are ordered in time

EXAMPLE precedence, simultaneity.

NOTE There is a limited number of ways to order objects which are collectively called ordering relations.

3.17

temporal unit

element in a time amount (3.18) that quantifies the length of a temporal interval (3.15) or a set of temporal

intervals (3.15)

NOTE 1 Adapted from Bunt (1985).

NOTE 2 In measurement systems, various units are defined for different purposes. Small units such as seconds and

minutes are defined to measure small temporal intervals; as one may want to avoid working with big numbers, for larger

temporal intervals, units such as week, year, decade, and century are defined.

NOTE 3 The amount of a temporal unit is called a measure.

3.18

time amount

quantity of time, measured by temporal units (3.17) over temporal intervals (3.15)

NOTE 1 Adapted from Bunt (1985).

NOTE 2 A time amount is a measure of time that can be expressed in terms of a number of temporal units, such as

“half an hour” or “30 minutes”.

3.19

tense

way that languages express the time at which an event (3.5) described by a sentence occurs

NOTE This is characterized as a property of a verb form. Noun forms will not be said to exhibit tense but rather

temporal markers.

3.20

TLINK

linking tag that represents a temporal relation between two temporal entities: namely, between two events

(3.5), two temporal expressions, or between a temporal expression and an event

NOTE 1 Adapted from Pustejovsky et al. (2004).

NOTE 2 Some ordering relations cannot be expressed by an ordering relation between two events because a signal, like

a temporal preposition, complicates the ordering or there is an ordering relation between a temporal signal and an event.

4 Overview

An understanding of temporal information is needed to better understand natural language texts in general.

Previous work in time stamping is a step in the right direction, but to fully appreciate the complexity of a text with

respect to time, the ability to order events and temporal expressions is needed. This part of ISO 24617 defines

ISO-TimeML, a markup language for time and events, which has been specifically designed for this task.

ISO-TimeML annotates all expressions having temporal import, broadly categorized as temporal expressions

and eventualities (situations, events, states, and activities). Temporal expressions and events participate in

temporal relationships (e.g. “before”, “simultaneous”), subordinating relationships (e.g. “intensional”, “factive”),

and aspectual relationships (e.g. “initiates”, “continues”). ISO-TimeML provides an additional expressive

capability of capturing and representing the complexities of these relationships.

TimeML, the precursor of ISO-TimeML, is already in use in a number of applications focusing on analysis

(manual and automatic) of news articles. The TimeBank corpus contains approximately 185 such documents

and has been validated against the most recent version of TimeML. The resulting output of a TimeML

annotated document is in XML, which allows for general XML validation methods to be used. In addition to

supporting interoperability among different temporal representation schemes, TimeML has been shown

adequate to support a mapping from the temporal information in a text to its formal representation in a Web

Ontology Language such as OWL-Time.

Unlike prior event annotation schemes, ISO-TimeML's somewhat unique definition of an event does not limit

the standard's applicability to specific natural language genres. An ISO-TimeML event is simply something

that can be related to another event or temporal expression using an ISO-TimeML relationship — thus an

ISO-TimeML-compliant representation can be adapted (derived) from the full standard specification,

appropriate to different genres, styles, domains, and applications. Future work will involve applying the

standard in such different contexts, and formulating guidelines and principles for appropriate use of

ISO-TimeML in a variety of language engineering environments.

5 Motivation and requirements

The identification of temporal and event expressions in natural language text is a critical component of any

robust information retrieval or language understanding system, and recently this has become an area of

intense research in computational linguistics and Artificial Intelligence. The importance of temporal awareness

to question answering systems has become more obvious as current systems strive to move beyond keyword

and simple named-entity extraction. Named-entity recognition has moved the fields of information retrieval and

information exploitation closer to access by content, by allowing some identification of names, locations and

products in texts. One of the major problems that has not been solved is the recognition of events and their

temporal anchorings in text. Events are naturally anchored in time within a narrative. Without a robust ability to

identify and extract events and their temporal anchoring from a text, the real aboutness of the text can be

missed. Moreover, since entities and their properties change over time, a database of assertions about

entities will be incomplete or incorrect if it does not capture how these properties are temporally updated. To

this end, event recognition drives basic inferences from text.

4 © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

As it happens, however, much of the temporal information in an article or narrative is left implicit in the text.

The exact temporal designation of events is rarely explicit and many temporal expressions are vague at best.

A crucial first step in the automatic extraction of information from such texts, for use in applications such as

automatic question answering or summarization, is the capacity to identify what events are being described

and to make explicit when these events occurred.

Another important point is that, although most of the information on the web is in natural language, it is

unlikely that it will ever be marked up for semantic retrieval, if that entails hand annotation. Natural language

programs will have to process the contents of web pages to produce annotations. Remarkable progress has

been made in the last decade in the use of statistical techniques for analysing text. However, these

techniques, for the most part, depend on having large amounts of annotated data, and annotations require an

annotation scheme. Hence, in addition to developing the necessary tools for temporal analysis, it is important

to enable for seamless integration into existing and emerging ontologies, such as OWL. Interest in temporal

analysis and event-based reasoning has contributed to the development of a specification language for events

and temporal expressions and their orderings (TimeML). Some issues relating to temporal and event

identification have remained unresolved, however, and ISO-TimeML has been designed to address these

issues. Specifically, four basic problems in event-temporal identification have been addressed in the design of

ISO-TimeML:

time anchoring of events (identifying an event and anchoring it in time);

ordering events with respect to one another (distinguishing lexical from discourse properties of temporal

ordering);

reasoning with contextually underspecified temporal expressions (temporal functions such as “last week”

and “two weeks before”);

reasoning about the persistence of events (how long does an event or the outcome of an event last).

The specification language, ISO-TimeML, is designed to address these issues, in addition to handling basic

tense and aspect features.

Linking a formal theory of time with an annotation scheme aimed at extracting rich temporal information from

natural language text is significant for at least two reasons. It will allow us to use the multitude of temporal

facts expressed in text as the ground propositions in a system for reasoning about temporal relations. It will

also constitute a forcing function for developing the coverage of a temporal reasoning system, as we

encounter phenomena not normally covered by such systems, such as complex descriptions of temporal

aggregates.

6 Basic concepts and metamodel

Regarding the temporal information in a document, a distinction can be made between (1) the temporal

metadata, regarding when the document was created, published, distributed, received, revised, etc., and (2)

the temporal properties of the events and situations that are described in the document. The former type of

information is associated with the document as a whole; information of the latter type will be associated in

annotations with parts of the text in the document, “markables” such as words and phrases.

Temporal objects and relations have been studied from logical and ontological points of view; well-known

studies include those by Allen (1984), Prior (1967), and more recently Hobbs and Pan (2004); see also the

collection of papers in Mani et al. (2005). The most common view of time, which underlies most natural

languages, is that time is an unbounded linear space running from a metaphorical “beginning of time” at minus

infinity to an equally metaphorical “end of time” at plus infinity. This linear space can be represented as a

straight line, the points of which correspond to moments in time; following Hobbs and Pan (2004), we will also

use the term “instant” to refer to time points. From a mathematical point of view, the points on the time line are

line segments of infinitesimally small size, corresponding to the intuition that a moment in time can, in principle,

be determined with any precision that one may wish.

For linguistic and philosophical reasons, several classifications have been proposed of verbs describing

various types of states or events, the Vendler classification being the best known (Vendler, 1967). For the

annotation of temporal information in text, not only verbs with their tenses and temporal modifications should

be considered, but also nouns, since nouns may also denote events and situations (“The meeting tomorrow”;

“The six o'clock news”). In TimeML, Pustejovsky et al. (2007) have proposed a classification of states and

events into seven categories. In the literature, a distinction is often made between events and states, where

events are commonly characterized as occurring at a point in time or during a certain definite interval,

whereas states may obtain for any indefinite stretch of time (“The Mediterranean Sea separates Europe from

Africa”). On a terminological note: the term “event” will henceforth be used as a generic term that also covers

such notions as “state”, “situation”, “action”, “process”, etc.; this broad notion of event has also been termed

“eventuality” (Bach, 1986).

In reality, nothing happens in infinitesimally small time; every event or state that occurs in reality (or in

someone's mind) requires more than zero time, although natural languages offer speakers the possibility to

express themselves as if something occurs at a precise instant (such as “I will call you at twelve o'clock”).

Since instants are formally a special kind of interval, a consistent approach to modelling the time that an event

occurs is to always use intervals, where it may happen that the interval associated with a particular event is

regarded as having zero length, and thus being an instant. This is reflected in the metamodel presented in

Figure 1, which uniformly relates events with temporal intervals.

The length of an interval can also occur as temporal information in a text, as in “I used twelve hours to read

that book” and “It takes seven minutes to walk to the station”. An expression such as “seven minutes” does

not denote an interval, but the length of an interval. It is the temporal equivalent of spatial distance (“seven

miles”). To describe the length of a temporal interval, one needs a unit of measurement, which may be

combined with a numerical expression to obtain an amount of time. The metamodel presented below therefore

includes the concept of an amount of time, related to intervals through the function length, and the auxiliary

concepts of temporal units and real numbers. (Moreover, in the ISO-TimeML semantics, different temporal

units are related through a c

...

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 24617-1

First edition

2012-01-15

Language resource management —

Semantic annotation framework

(SemAF) —

Part 1:

Time and events (SemAF-Time,

ISO-TimeML)

Gestion des ressources langagières — Cadre d'annotation sémantique

(SemAF) —

Partie 1: Temps et événements (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Reference number

©

ISO 2012

© ISO 2012

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from either ISO at the address below or

ISO's member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

Contents Page

Foreword . vi

Introduction . vii

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Overview . 4

5 Motivation and requirements . 4

6 Basic concepts and metamodel . 5

7 Specification of ISO-TimeML . 8

7.1 Overview . 8

7.2 Abstract syntax . 8

7.2.1 Introduction . 8

7.2.2 Conceptual inventory . 9

7.2.3 Syntax rules . 9

7.3 Concrete XML-based syntax . 10

7.3.1 TimeML vs. ISO-TimeML: Stand-off annotation and other differences . 10

7.3.2 Naming conventions . 12

7.3.3 Example annotations . 12

7.3.4 Basic elements: , , and . 12

7.3.5 Link elements: , , and . 18

7.3.6 Other tags: , and . 22

8 Towards a semantics for ISO-TimeML . 26

8.1 Overview . 26

8.2 Tense and aspect in language . 26

8.2.1 Tense . 26

8.2.2 Aspect . 26

8.3 Temporal relations . 27

8.4 An interval-based semantics for ISO-TimeML . 28

8.4.1 Technical preliminaries for interval temporal logic . 28

8.4.2 Basic event-structure . 29

8.4.3 The interpretation of . 31

8.4.4 Interpretive rule summary . 36

8.5 An event-based semantics for ISO-TimeML . 37

8.5.1 Introduction . 37

8.5.2 Defining an event-based semantics . 38

Annex A (normative) Core annotation guidelines . 41

A.1 Introduction . 41

A.2 ISO-TimeML elements and their attributes . 41

A.2.1 The element . 41

A.2.2 The element . 48

A.2.3 The element . 55

A.3 The link elements: , , and . 56

A.3.1 Overview . 56

A.3.2 The element . 56

A.3.3 The element . 59

A.3.4 The element . 61

A.3.5 The element . 62

Annex B (informative) Completely annotated examples .63

B.1 Complex TIMEX3 examples .63

B.2 Complex TLINK and SLINK examples .64

B.3 Causative examples .67

Annex C (informative) Event and temporal annotations for Chinese .68

Annex D (informative) Annotation for Italian fragment .74

D.1 Introduction .74

D.2 Basic references .74

D.3 ISO-TimeML elements and their attributes .74

D.3.1 How to annotate EVENTs .74

D.3.2 Event identification and tag span .75

D.3.3 What NOT to tag .78

D.3.4 Introductory note .78

D.4 The element .81

D.5 The link tags .82

D.6 Informative: Examples of tense, aspect and mood annotation in Italian.82

D.7 Sample of Italian annotation .84

Annex E (informative) Temporal annotation of predicates in Korean .89

E.1 Introduction .89

E.2 Basic references .89

E.3 Morpholoy of Korean predicates .89

E.4 Temporal structure: informative .91

E.5 Temporal annotation of non-Latin texts .92

E.6 Tense .93

E.6.1 Tense markers .93

E.6.2 Annotation guidelines for the attribute @tense .95

E.6.3 Contextual interpretation of tense .96

E.7 Aspect . 114

E.7.1 Aspect markers . 114

E.7.2 Annotation of aspect markers . 115

E.7.3 Interpretation of aspectual features. 116

E.7.4 Interpretation conditions of aspect . 118

E.8 Modality . 118

E.8.1 Conjectural modal markers . 118

E.8.2 Annotation of modality CONJECTURAL . 119

E.8.3 Interpretation of modality CONJECTURAL . 120

E.9 Mood . 120

E.9.1 Mood markers . 120

E.9.2 Annotation of mood RETROSPECTIVE . 121

E.9.3 Interpretation of RETROSPECTIVE mood . 122

E.10 Specific values for attributes in Korean . 122

E.11 Summary . 122

Annex F (informative) Past and current activities on temporal and event annotation . 124

F.1 Introductory remarks . 124

F.2 Annotating temporal expressions . 124

F.3 Annotating events . 125

F.4 Annotating relations between times and events . 127

F.4.1 Ways of capturing time-event relational information . 127

F.4.2 Subordinating and aspectual relations . 129

Annex G (informative) Tools and templates . 130

G.1 Overview . 130

G.2 Annotation tools and templates . 130

G.2.1 Overview . 130

G.2.2 The ALEMBIC workbench . 131

G.2.3 The CALLISTO toolkit . 131

G.2.4 The TANGO temporal relation editor . 131

G.3 Analytic tools . 132

iv © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

G.3.1 Overview . 132

G.3.2 The TARSQI toolkit . 132

G.3.3 The IBM TimeML annotator . 133

G.3.4 The Amsterdam temporal component extractor . 133

G.3.5 The Time Calculus analyser . 133

Annex H (normative) Specification . 134

H.1 Requirement . 134

H.2 Attribute classes . 134

H.2.1 att.anchored . 134

H.2.2 att.annotate . 135

H.2.3 att.id . 135

H.2.4 att.lang . 135

H.2.5 att.linguistic . 136

H.2.6 att.pointing . 138

H.2.7 att.typed . 138

H.3 Elements . 139

H.3.1 . 139

H.3.2 . 139

H.3.3 . 140

H.3.4 . 141

H.3.5 . 141

H.3.6 . 142

H.3.7 . 143

H.3.8 . 145

H.3.9

H.3.10 . 146

H.3.11

H.3.12 . 146

Bibliography . 147

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies

(ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through ISO

technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical committee has been

established has the right to be represented on that committee. International organizations, governmental and

non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work. ISO collaborates closely with the

International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of electrotechnical standardization.

International Standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

The main task of technical committees is to prepare International Standards. Draft International Standards

adopted by the technical committees are circulated to the member bodies for voting. Publication as an

International Standard requires approval by at least 75 % of the member bodies casting a vote.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of patent

rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

ISO 24617-1 was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 37, Terminology and other language and content

resources, Subcommittee SC 4, Language resource management.

ISO 24617 consists of the following parts, under the general title Language resource management —

Semantic annotation framework (SemAF):

Part 1: Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

Part 2: Dialogue acts

The following parts are under preparation:

Part 4: Semantic roles (SemAF-SRL)

Part 5: Discourse structure (SemAF-DS)

The following parts are planned:

Part 3: Named entities (SemAF-NE)

Part 6: Principles of semantic annotation

Part 7: Spatial information (ISO-Space)

Part 8: Relations in Discourse (SemAF-DRel)

vi © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

Introduction

This part of ISO 24617 results from the agreement between the TimeML Working Group and the ISO Working

Group, ISO/TC 37/SC 4/WG 2, Language resource management – Semantic annotation, that a joint activity

should take place to accommodate the two existing documents for annotating temporal information,

TimeML 1.2.1 and TimeML Annotation Guidelines, into ISO international standards. This work should lead to

the achievement of two objectives:

modification of the two documents in conformance to the ISO International Standards;

verification of the annotation guidelines for a wide coverage of multilingual resources.

It should be noted that this part of ISO 24617 provides normative guidelines not just for temporal information,

but also for information content in various types of events in English as well as other languages.

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 24617-1:2012(E)

Language resource management — Semantic annotation

framework (SemAF) —

Part 1:

Time and events (SemAF-Time, ISO-TimeML)

1 Scope

Temporal information in natural language texts is an increasingly important component to the understanding of

those texts. This part of ISO 24617, SemAF-Time, specifies a formalized XML-based markup language called

ISO-TimeML, with a systematic way to extract and represent temporal information, as well as to facilitate the

exchange of temporal information, both between operational language processing systems and between

different temporal representation schemes. The use of guidelines for temporal annotation has been fully

attested with examples from the TimeBank corpus, a collection of 183 documents that have been annotated

by TimeML before the current version of ISO-TimeML was formulated.

NOTE Throughout this document, SemAF-Time refers to the ISO 24617-1, while ISO-TimeML refers to the

annotation language specified in this document.

2 Normative references

The following referenced documents are indispensable for the application of this document. For dated

references, only the edition cited applies. For undated references, the latest edition of the referenced

document (including any amendments) applies.

NOTE The first reference shows how dates and times are represented and the second provides a format for the

standoff representation of ISO-TimeML annotation presented here.

ISO 8601:2004, Data elements and interchange formats — Information interchange — Representation of

dates and times

ISO 24612:2011, Language resource management — Linguistic annotation framework (LAF)

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions in ISO 8601:2004 and the following apply.

NOTE The terms and definitions provided below are provided to clarify the terminology relating to the metamodel,

specification, and semantics of ISO-TimeML. Terminology derived from XML and other formal languages as well as from

general temporal logics is not defined here.

3.1

ALINK

linking tag that represents a phase relation between an aspectual verb (or morpheme) and a predicate

denoting an event (3.5)

3.2

annotation

process of adding information to segments of language data or that information itself

3.3

beginning

instant (3.6) at which a temporal interval (3.17) begins

NOTE Adapted from Hobbs and Pan (2004).

3.4

end

instant (3.6) at which a temporal interval (3.17) ends

NOTE Adapted from Hobbs and Pan (2004).

3.5

event

eventuality

something that can be said to obtain or hold true, to happen or to occur

NOTE The term “event” is used here with a very broad notion of event, which includes all kinds of actions, states,

processes, etc. It is not to be confused with the more narrow notion of event as something that happens at a certain point

in time (such as the clock striking 2, or waking up) or during a short period of time (such as laughing).

3.6

instant

point in time with no interior points

NOTE Time is often viewed as a straight line from minus infinity to plus infinity. In this view, time is formed by an

infinite sequence of points. An instant can also be seen as an infinitesimally small interval. Cf. OWL-Time Ontology for

“instant”: http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-time/.

3.7

markable

entity in general, or segment of a text in particular, that is subject to an annotation (3.2)

3.8

MLINK

linking tag that represents the measurement of the duration of an event (3.5) or the measurement of the

length of a (possibly discontinuous) time span

3.9

point of event

instant (3.6) at which the event (3.5) mentioned in a given utterance occurs

NOTE Next to a point of speech, a point of event also needs to be defined in order to interpret tense. For example, in

“Arthur smiled”, the temporal location of the point of event can be defined as being prior to the point of speech.

3.10

point of reference

instant (3.6) of temporal perspective on the event (3.5) in a given utterance

NOTE 1 “Arthur will have gone by tomorrow”, where the point of speech is now, the point of event is some time in the

future, but before the point of reference referred to by “tomorrow”.

NOTE 2 To locate certain tenses in time, a third anchor point is also required, defined as the point of reference.

3.11

point of speech

time unit (3.17) at which a given utterance occurs

NOTE 1 The notion of point of speech is needed in order to interpret tense. This requires the use of anchor points in

time, of which the point of speech is one (point of text, see 3.12, is another one). For example, in “Arthur smiled”, the point

of speech is the time that the utterance is made.

NOTE 2 For a document as a whole, this may be considered to be the same as the document creation time.

2 © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

3.12

point of text

instant (3.6) at which reported speech is anchored

NOTE It is the point of time considered in the text of the speech. So for example, when a person is telling a story, it is

not enough to know the point of the speech itself (the document creation time), but the point at which the speech in the

story is taking place.

3.13

representation

format in which an annotation (3.2) is rendered, for instance in XML, independent of its content

3.14

SLINK

linking tag that represents a subordinating relation between two events (3.5)

3.15

temporal interval

period

uninterrupted stretch of time, with internal point structure.

NOTE 1 Adapted from WordNet.

NOTE 2 Time is often viewed as a straight line from minus infinity to plus infinity. A temporal interval is a part of that

line without any holes, containing all the points between its beginning and its end.

NOTE 3 In mathematics, an important issue is whether an interval includes its beginning and its end (is “closed”) or not

(is “open” or “half-open”). In natural language descriptions of intervals this may also be relevant, as when describing an

interval in terms of a number of days, but not with the same granularity as in mathematics. Cf. OWL-Time Ontology for

“interval”: http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-time/.

3.16

temporal ordering relation

relation that determines how objects are ordered in time

EXAMPLE precedence, simultaneity.

NOTE There is a limited number of ways to order objects which are collectively called ordering relations.

3.17

temporal unit

element in a time amount (3.18) that quantifies the length of a temporal interval (3.15) or a set of temporal

intervals (3.15)

NOTE 1 Adapted from Bunt (1985).

NOTE 2 In measurement systems, various units are defined for different purposes. Small units such as seconds and

minutes are defined to measure small temporal intervals; as one may want to avoid working with big numbers, for larger

temporal intervals, units such as week, year, decade, and century are defined.

NOTE 3 The amount of a temporal unit is called a measure.

3.18

time amount

quantity of time, measured by temporal units (3.17) over temporal intervals (3.15)

NOTE 1 Adapted from Bunt (1985).

NOTE 2 A time amount is a measure of time that can be expressed in terms of a number of temporal units, such as

“half an hour” or “30 minutes”.

3.19

tense

way that languages express the time at which an event (3.5) described by a sentence occurs

NOTE This is characterized as a property of a verb form. Noun forms will not be said to exhibit tense but rather

temporal markers.

3.20

TLINK

linking tag that represents a temporal relation between two temporal entities: namely, between two events

(3.5), two temporal expressions, or between a temporal expression and an event

NOTE 1 Adapted from Pustejovsky et al. (2004).

NOTE 2 Some ordering relations cannot be expressed by an ordering relation between two events because a signal, like

a temporal preposition, complicates the ordering or there is an ordering relation between a temporal signal and an event.

4 Overview

An understanding of temporal information is needed to better understand natural language texts in general.

Previous work in time stamping is a step in the right direction, but to fully appreciate the complexity of a text with

respect to time, the ability to order events and temporal expressions is needed. This part of ISO 24617 defines

ISO-TimeML, a markup language for time and events, which has been specifically designed for this task.

ISO-TimeML annotates all expressions having temporal import, broadly categorized as temporal expressions

and eventualities (situations, events, states, and activities). Temporal expressions and events participate in

temporal relationships (e.g. “before”, “simultaneous”), subordinating relationships (e.g. “intensional”, “factive”),

and aspectual relationships (e.g. “initiates”, “continues”). ISO-TimeML provides an additional expressive

capability of capturing and representing the complexities of these relationships.

TimeML, the precursor of ISO-TimeML, is already in use in a number of applications focusing on analysis

(manual and automatic) of news articles. The TimeBank corpus contains approximately 185 such documents

and has been validated against the most recent version of TimeML. The resulting output of a TimeML

annotated document is in XML, which allows for general XML validation methods to be used. In addition to

supporting interoperability among different temporal representation schemes, TimeML has been shown

adequate to support a mapping from the temporal information in a text to its formal representation in a Web

Ontology Language such as OWL-Time.

Unlike prior event annotation schemes, ISO-TimeML's somewhat unique definition of an event does not limit

the standard's applicability to specific natural language genres. An ISO-TimeML event is simply something

that can be related to another event or temporal expression using an ISO-TimeML relationship — thus an

ISO-TimeML-compliant representation can be adapted (derived) from the full standard specification,

appropriate to different genres, styles, domains, and applications. Future work will involve applying the

standard in such different contexts, and formulating guidelines and principles for appropriate use of

ISO-TimeML in a variety of language engineering environments.

5 Motivation and requirements

The identification of temporal and event expressions in natural language text is a critical component of any

robust information retrieval or language understanding system, and recently this has become an area of

intense research in computational linguistics and Artificial Intelligence. The importance of temporal awareness

to question answering systems has become more obvious as current systems strive to move beyond keyword

and simple named-entity extraction. Named-entity recognition has moved the fields of information retrieval and

information exploitation closer to access by content, by allowing some identification of names, locations and

products in texts. One of the major problems that has not been solved is the recognition of events and their

temporal anchorings in text. Events are naturally anchored in time within a narrative. Without a robust ability to

identify and extract events and their temporal anchoring from a text, the real aboutness of the text can be

missed. Moreover, since entities and their properties change over time, a database of assertions about

entities will be incomplete or incorrect if it does not capture how these properties are temporally updated. To

this end, event recognition drives basic inferences from text.

4 © ISO 2012 – All rights reserved

As it happens, however, much of the temporal information in an article or narrative is left implicit in the text.

The exact temporal designation of events is rarely explicit and many temporal expressions are vague at best.

A crucial first step in the automatic extraction of information from such texts, for use in applications such as

automatic question answering or summarization, is the capacity to identify what events are being described

and to make explicit when these events occurred.

Another important point is that, although most of the information on the web is in natural language, it is

unlikely that it will ever be marked up for semantic retrieval, if that entails hand annotation. Natural language

programs will have to process the contents of web pages to produce annotations. Remarkable progress has

been made in the last decade in the use of statistical techniques for analysing text. However, these

techniques, for the most part, depend on having large amounts of annotated data, and annotations require an

annotation scheme. Hence, in addition to developing the necessary tools for temporal analysis, it is important

to enable for seamless integration into existing and emerging ontologies, such as OWL. Interest in temporal

analysis and event-based reasoning has contributed to the development of a specification language for events

and temporal expressions and their orderings (TimeML). Some issues relating to temporal and event

identification have remained unresolved, however, and ISO-TimeML has been designed to address these

issues. Specifically, four basic problems in event-temporal identification have been addressed in the design of

ISO-TimeML:

time anchoring of events (identifying an event and anchoring it in time);

ordering events with respect to one another (distinguishing lexical from discourse properties of temporal

ordering);

reasoning with contextually underspecified temporal expressions (temporal functions such as “last week”

and “two weeks before”);

reasoning about the persistence of events (how long does an event or the outcome of an event last).

The specification language, ISO-TimeML, is designed to address these issues, in addition to handling basic

tense and aspect features.

Linking a formal theory of time with an annotation scheme aimed at extracting rich temporal information from

natural language text is significant for at least two reasons. It will allow us to use the multitude of temporal

facts expressed in text as the ground propositions in a system for reasoning about temporal relations. It will

also constitute a forcing function for developing the coverage of a temporal reasoning system, as we

encounter phenomena not normally covered by such systems, such as complex descriptions of temporal

aggregates.

6 Basic concepts and metamodel

Regarding the temporal information in a document, a distinction can be made between (1) the temporal

metadata, regarding when the document was created, published, distributed, received, revised, etc., and (2)

the temporal properties of the events and situations that are described in the document. The former type of

information is associated with the document as a whole; information of the latter type will be associated in

annotations with parts of the text in the document, “markables” such as words and phrases.

Temporal objects and relations have been studied from logical and ontological points of view; well-known

studies include those by Allen (1984), Prior (1967), and more recently Hobbs and Pan (2004); see also the

collection of papers in Mani et al. (2005). The most common view of time, which underlies most natural

languages, is that time is an unbounded linear space running from a metaphorical “beginning of time” at minus

infinity to an equally metaphorical “end of time” at plus infinity. This linear space can be represented as a

straight line, the points of which correspond to moments in time; following Hobbs and Pan (2004), we will also

use the term “instant” to refer to time points. From a mathematical point of view, the points on the time line are

line segments of infinitesimally small size, corresponding to the intuition that a moment in time can, in principle,

be determined with any precision that one may wish.

For linguistic and philosophical reasons, several classifications have been proposed of verbs describing

various types of states or events, the Vendler classification being the best known (Vendler, 1967). For the

annotation of temporal information in text, not only verbs with their tenses and temporal modifications should

be considered, but also nouns, since nouns may also denote events and situations (“The meeting tomorrow”;

“The six o'clock news”). In TimeML, Pustejovsky et al. (2007) have proposed a classification of states and

events into seven categories. In the literature, a distinction is often made between events and states, where

events are commonly characterized as occurring at a point in time or during a certain definite interval,

whereas states may obtain for any indefinite stretch of time (“The Mediterranean Sea separates Europe from

Africa”). On a terminological note: the term “event” will henceforth be used as a generic term that also covers

such notions as “state”, “situation”, “action”, “process”, etc.; this broad notion of event has also been termed

“eventuality” (Bach, 1986).

In reality, nothing happens in infinitesimally small time; every event or state that occurs in reality (or in

someone's mind) requires more than zero time, although natural languages offer speakers the possibility to

express themselves as if something occurs at a precise instant (such as “I will call you at twelve o'clock”).

Since instants are formally a special kind of interval, a consistent approach to modelling the time that an event

occurs is to always use intervals, where it may happen that the interval associated with a particular event is

regarded as having zero length, and thus being an instant. This is reflected in the metamodel presented in

Figure 1, which uniformly relates events with temporal intervals.

The length of an interval can also occur as temporal information in a text, as in “I used twelve hours to read

that book” and “It takes seven minutes to walk to the station”. An expression such as “seven minutes” does

not denote an interval, but the length of an interval. It is the temporal equivalent of spatial distance (“seven

miles”). To describe the length of a temporal interval, one needs a unit of measurement, which may be

combined with a numerical expression to obtain an amount of time. The metamodel presented below therefore

includes the concept of an amount of time, related to intervals through the function length, and the auxiliary

concepts of temporal units and real numbers. (Moreover, in the ISO-TimeML semantics, different temporal

units are related through a conversion function, stipulating such things as 1 hour = 60 minutes;

1 day = 24 hours, etc. An amount of time can be characterized equivalently by as many pairs temporal unit> as there are temporal units, the equivalence being defined through the numerical conversions

between units [see Bunt (1985)].

Regarding the temporal anchoring of events in time, it may be noted that the association of a temporal interval

with an event does not necessarily mean that the event took place during every moment within that interval.

When someone says “I've been working on my presentation from 8.30 to 12 o'clock”, that presumably does

not mean that the speaker has been working on his presentation for every single moment between 8.30 and

12 o'clock; there must have been interruptions for having some coffee, going to the bathroom, etc. In such a

case it is more accurate to anchor the event at the time span starting at 8.30 and ending at 12 o'clock, a “time

span” being understood as a period of time that may have “holes”, where the event was interrupted. The

metamodel shown in Figure 1 does not distinguish time spans, but reflects the assumption that whether an

event occurs during an interval, with or without any interruptions, can only be decided on a case by case basis,

and is best modelled as a property of the temporal anchoring relation applied to a specific event.

ISO 24612:2011 insists on the use o

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...