ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014

(Main)Information technology — Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces — Guidelines for the preparation of Language-Independent Service Specifications (LISS)

Information technology — Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces — Guidelines for the preparation of Language-Independent Service Specifications (LISS)

ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 provides guidelines to those concerned with developing specifications of information technology services and their interfaces intended for use by clients of the services, in particular by external applications that do not necessarily all share the environment and assumptions of one particular programming language. The guidelines do not directly or fully cover all aspects of service or interface specifications, but they do cover those aspects required to achieve language independence, i.e. required to make a specification neutral with respect to the language environment from which the service is invoked. The guidelines are primarily concerned with the interface between the service and the external applications making use of the service, including the special case where the service itself is already specified in a language-dependent way but needs to be invoked from environments of other languages. Language bindings, already addressed by another Technical Report, ISO/IEC/TR 10182, are dealt with by providing advice on how to use the two Technical Reports together. ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 provides technical guidelines, rather than organizational or administrative guidelines for the management of the development process, though in some cases the technical guidelines may have organizational or administrative implications.

Technologies de l'information — Langages de programmation, leurs environnements et interfaces du logiciel d'exploitation — Lignes directrices pour l'élaboration de spécifications de service indépendantes du langage (LISS)

General Information

- Status

- Withdrawn

- Publication Date

- 23-Nov-2014

- Withdrawal Date

- 23-Nov-2014

- Current Stage

- 9599 - Withdrawal of International Standard

- Start Date

- 30-Jan-2018

- Completion Date

- 12-Feb-2026

Relations

- Effective Date

- 16-Jul-2016

Get Certified

Connect with accredited certification bodies for this standard

BSI Group

BSI (British Standards Institution) is the business standards company that helps organizations make excellence a habit.

NYCE

Mexican standards and certification body.

Sponsored listings

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 is a technical report published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Information technology — Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces — Guidelines for the preparation of Language-Independent Service Specifications (LISS)". This standard covers: ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 provides guidelines to those concerned with developing specifications of information technology services and their interfaces intended for use by clients of the services, in particular by external applications that do not necessarily all share the environment and assumptions of one particular programming language. The guidelines do not directly or fully cover all aspects of service or interface specifications, but they do cover those aspects required to achieve language independence, i.e. required to make a specification neutral with respect to the language environment from which the service is invoked. The guidelines are primarily concerned with the interface between the service and the external applications making use of the service, including the special case where the service itself is already specified in a language-dependent way but needs to be invoked from environments of other languages. Language bindings, already addressed by another Technical Report, ISO/IEC/TR 10182, are dealt with by providing advice on how to use the two Technical Reports together. ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 provides technical guidelines, rather than organizational or administrative guidelines for the management of the development process, though in some cases the technical guidelines may have organizational or administrative implications.

ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 provides guidelines to those concerned with developing specifications of information technology services and their interfaces intended for use by clients of the services, in particular by external applications that do not necessarily all share the environment and assumptions of one particular programming language. The guidelines do not directly or fully cover all aspects of service or interface specifications, but they do cover those aspects required to achieve language independence, i.e. required to make a specification neutral with respect to the language environment from which the service is invoked. The guidelines are primarily concerned with the interface between the service and the external applications making use of the service, including the special case where the service itself is already specified in a language-dependent way but needs to be invoked from environments of other languages. Language bindings, already addressed by another Technical Report, ISO/IEC/TR 10182, are dealt with by providing advice on how to use the two Technical Reports together. ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 provides technical guidelines, rather than organizational or administrative guidelines for the management of the development process, though in some cases the technical guidelines may have organizational or administrative implications.

ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 35.060 - Languages used in information technology. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to ISO/IEC TR 14369:2018. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014 is available in PDF format for immediate download after purchase. The document can be added to your cart and obtained through the secure checkout process. Digital delivery ensures instant access to the complete standard document.

Standards Content (Sample)

TECHNICAL ISO/IEC TR

REPORT 14369

First edition

2014-12-01

Information technology —

Programming languages, their

environments and system software

interfaces — Guidelines for the

preparation of Language-Independent

Service Specifications (LISS)

Technologies de l’information — Langages de programmation,

leurs environnements et interfaces du logiciel d’exploitation —

Lignes directrices pour l’élaboration de spécifications de service

indépendantes du langage (LISS)

Reference number

©

ISO/IEC 2014

© ISO/IEC 2014

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior

written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of

the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

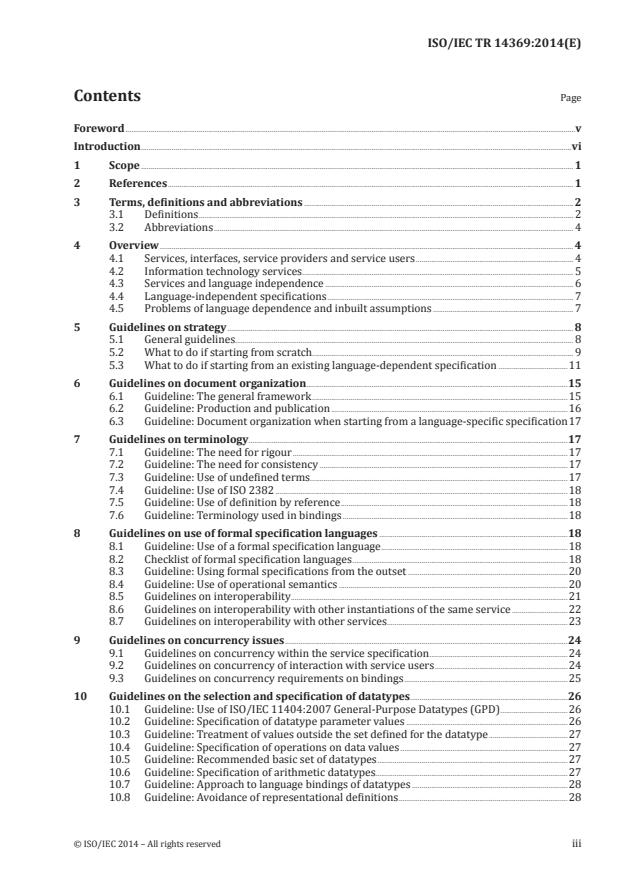

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction .vi

1 Scope . 1

2 References . 1

3 Terms, definitions and abbreviations . 2

3.1 Definitions . 2

3.2 Abbreviations . 4

4 Overview . 4

4.1 Services, interfaces, service providers and service users . 4

4.2 Information technology services . 5

4.3 Services and language independence . 6

4.4 Language-independent specifications . 7

4.5 Problems of language dependence and inbuilt assumptions . 7

5 Guidelines on strategy . 8

5.1 General guidelines. 8

5.2 What to do if starting from scratch. 9

5.3 What to do if starting from an existing language-dependent specification .11

6 Guidelines on document organization.15

6.1 Guideline: The general framework .15

6.2 Guideline: Production and publication .16

6.3 Guideline: Document organization when starting from a language-specific specification 17

7 Guidelines on terminology .17

7.1 Guideline: The need for rigour .17

7.2 Guideline: The need for consistency .17

7.3 Guideline: Use of undefined terms .17

7.4 Guideline: Use of ISO 2382 .18

7.5 Guideline: Use of definition by reference .18

7.6 Guideline: Terminology used in bindings .18

8 Guidelines on use of formal specification languages .18

8.1 Guideline: Use of a formal specification language .18

8.2 Checklist of formal specification languages .18

8.3 Guideline: Using formal specifications from the outset .20

8.4 Guideline: Use of operational semantics .20

8.5 Guidelines on interoperability .21

8.6 Guidelines on interoperability with other instantiations of the same service .22

8.7 Guidelines on interoperability with other services .23

9 Guidelines on concurrency issues .24

9.1 Guidelines on concurrency within the service specification .24

9.2 Guidelines on concurrency of interaction with service users .24

9.3 Guidelines on concurrency requirements on bindings .25

10 Guidelines on the selection and specification of datatypes.26

10.1 Guideline: Use of ISO/IEC 11404:2007 General-Purpose Datatypes (GPD) .26

10.2 Guideline: Specification of datatype parameter values .26

10.3 Guideline: Treatment of values outside the set defined for the datatype .27

10.4 Guideline: Specification of operations on data values .27

10.5 Guideline: Recommended basic set of datatypes .27

10.6 Guideline: Specification of arithmetic datatypes.27

10.7 Guideline: Approach to language bindings of datatypes .28

10.8 Guideline: Avoidance of representational definitions .28

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved iii

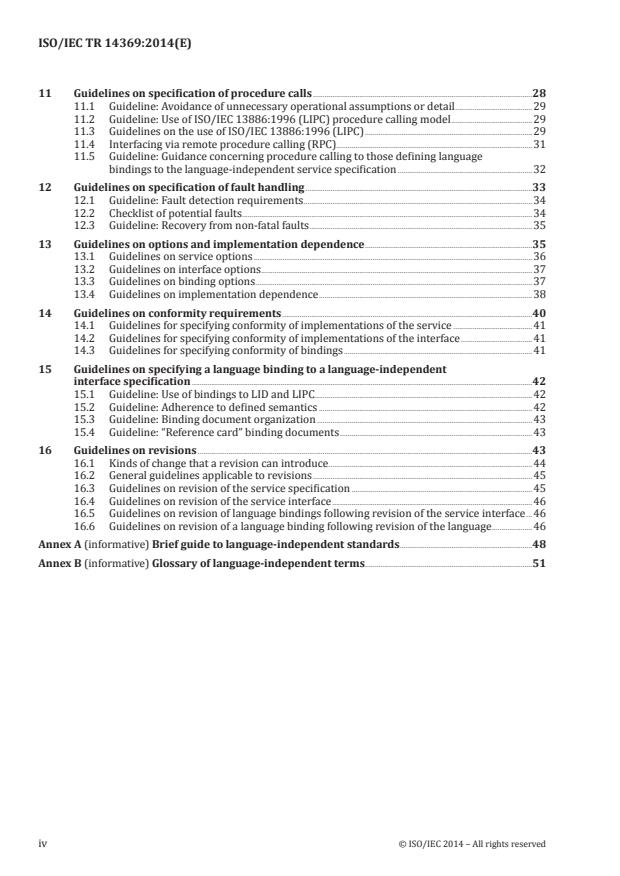

11 Guidelines on specification of procedure calls .28

11.1 Guideline: Avoidance of unnecessary operational assumptions or detail .29

11.2 Guideline: Use of ISO/IEC 13886:1996 (LIPC) procedure calling model .29

11.3 Guidelines on the use of ISO/IEC 13886:1996 (LIPC) .29

11.4 Interfacing via remote procedure calling (RPC).31

11.5 Guideline: Guidance concerning procedure calling to those defining language

bindings to the language-independent service specification .32

12 Guidelines on specification of fault handling .33

12.1 Guideline: Fault detection requirements .34

12.2 Checklist of potential faults .34

12.3 Guideline: Recovery from non-fatal faults .35

13 Guidelines on options and implementation dependence .35

13.1 Guidelines on service options .36

13.2 Guidelines on interface options .37

13.3 Guidelines on binding options .37

13.4 Guidelines on implementation dependence .38

14 Guidelines on conformity requirements .40

14.1 Guidelines for specifying conformity of implementations of the service .41

14.2 Guidelines for specifying conformity of implementations of the interface .41

14.3 Guidelines for specifying conformity of bindings .41

15 Guidelines on specifying a language binding to a language-independent

interface specification .42

15.1 Guideline: Use of bindings to LID and LIPC .42

15.2 Guideline: Adherence to defined semantics .42

15.3 Guideline: Binding document organization .43

15.4 Guideline: “Reference card” binding documents .43

16 Guidelines on revisions .43

16.1 Kinds of change that a revision can introduce .44

16.2 General guidelines applicable to revisions .45

16.3 Guidelines on revision of the service specification .45

16.4 Guidelines on revision of the service interface .46

16.5 Guidelines on revision of language bindings following revision of the service interface .46

16.6 Guidelines on revision of a language binding following revision of the language .46

Annex A (informative) Brief guide to language-independent standards .48

Annex B (informative) Glossary of language-independent terms .51

iv © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2. www.iso.org/directives

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of any

patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or on

the ISO list of patent declarations received. www.iso.org/patents

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation on the meaning of ISO specific terms and expressions related to conformity

assessment, as well as information about ISO’s adherence to the WTO principles in the Technical Barriers

to Trade (TBT), see the following URL: Foreword - Supplementary information

The committee responsible for this document is ISO/IEC JTC 1, Information technology, subcommittee

SC 22, Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved v

Introduction

This Technical Report is dedicated to Brian L. Meek in grateful recognition of his leadership and vision in

the development of the concepts on programming language independent specifications, and his efforts

in producing a set of standards documents in this area. Without his commitment this Technical Report

never would have been published.

0.1 Background

This Technical Report provides guidance to those writing specifications of services, and of interfaces to

services, in a language-independent way, in particular as standards. It can be regarded as complementary

to ISO/IEC/TR 10182, which provides guidance to those performing language bindings for such services

and their interfaces.

NOTE 1 Here and throughout, “language”, on its own or in compounds like “language-independent”, means

“programming language”, not “specification language” nor “natural (human) language”, unless explicitly stated.

NOTE 2 A “language-independent” service or interface specification may be expressed using either or both of a

natural language like English or a formal specification language like VDM-SL or Z; in a sense, a specification might

be regarded as “dependent” on (say) VDM-SL. The term “language-independent” does not imply otherwise, since

it refers only to the situation where programming language(s) might otherwise be used in defining the service or

interface.

The development of this Technical Report was prompted by the existence of an earlier draft IEEE Technical

Report (IEEE TCOS-SCC Technical Report on Programming Language Independent Specification Methods,

draft 4, May 1991). The TCOS draft was concerned with specifications of services in a POSIX systems

environment, and as such contained much detailed POSIX-specific guidance; nevertheless it was clear

that many of the principles, if not the detail, were applicable much more generally. This Technical Report

was conceived as a means of providing such more general guidance. Because of the very different formats,

and the POSIX-related detail in the TCOS draft, there is almost no direct correspondence between the

two documents, except in the discussion of the benefits of a language-independent principles below.

However, the spirit and principles of the TCOS draft were of great value in developing this Technical

Report, and reappear herein, albeit in much altered and more general form.

NOTE 3 The TCOS draft has not in fact been published, as the result of an IEEE decision to concentrate activities

in other POSIX areas.

0.2 Principles

Service or interface specifications that are independent of any particular language, particularly

when embodied in recognized standards, are increasingly seen as an important factor in promoting

interoperation and substitution of system components, and reducing dependence on and consequent

limitations due to particular language platforms.

NOTE It is of course possible for a specification to be “independent” of a particular language in a formal sense,

but still be dependent on it through inbuilt assumptions derived from that language which do not necessarily hold

for other languages. The term “language-independent” here is meant in a much stronger sense than that, though

complete independence from all inbuilt assumptions may be difficult if not impossible to achieve.

Potential benefits from language-independent service or interface specifications include:

— A language-independent interface specification specifies those requirements that are common to all

language bindings to that interface, and hence provides a specification to which language bindings

may conform.

— A language-independent interface specification is a re-usable component for constructing language

bindings.

— A language-independent interface specification aids the construction of language bindings by

providing a common reference to which all bindings can relate. Through this common reference

it is possible to make use of pre-existing language bindings to language-independent standards

vi © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

for common features such as datatypes and procedure calls, and to other language-independent

specifications with related concepts.

— A language-independent service or interface specification provides an abstract specification of a

service in isolation from language-dependent extensions or restrictions, and hence facilitates more

rigorous modelling of services and interfaces.

— Language-independent service specifications facilitate the specification of relationships between

one service and another, by making it easier to relate common concepts than is generally possible

when the specifications are dependent on different languages.

— A language-independent interface specification facilitates the definition of relationships between

different language bindings to a common service (such as requirements for interoperability between

applications based on different languages that are sharing a common service implementation), by

providing a common reference specification to which all the languages can relate.

— A language-independent interface specification facilitates the definition of relations between

bindings to multiple services, including the requirements on management of multiple name spaces.

— fort and resources needed to ensure compatibility and consistency of behaviour between

implementations of the same service in different languages or between applications based on

different languages using the same interface.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved vii

TECHNICAL REPORT ISO/IEC TR 14369:2014(E)

Information technology — Programming languages,

their environments and system software interfaces —

Guidelines for the preparation of Language-Independent

Service Specifications (LISS)

1 Scope

This Technical Report provides guidelines to those concerned with developing specifications of

information technology services and their interfaces intended for use by clients of the services, in

particular by external applications that do not necessarily all share the environment and assumptions of

one particular programming language. The guidelines do not directly or fully cover all aspects of service

or interface specifications, but they do cover those aspects required to achieve language independence,

i.e. required to make a specification neutral with respect to the language environment from which the

service is invoked. The guidelines are primarily concerned with the interface between the service and

the external applications making use of the service, including the special case where the service itself

is already specified in a language-dependent way but needs to be invoked from environments of other

languages. Language bindings, already addressed by another Technical Report, ISO/IEC/TR 10182, are

dealt with by providing advice on how to use the two Technical Reports together.

This Technical Report provides technical guidelines, rather than organizational or administrative

guidelines for the management of the development process, though in some cases the technical guidelines

may have organizational or administrative implications.

2 References

The following documents, in whole or in part, are normatively referenced in this document and are

indispensable for its application. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For undated

references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 8807:1989, Information processing systems — Open Systems Interconnection — LOTOS — A formal

description technique based on the temporal ordering of observational behaviour

1)

ISO/IEC 9074:1997 , Information technology — Open Systems Interconnection — Estelle: A formal

description technique based on an extended state transition model Amendment 1)

ISO/IEC/TR 10034:1990, Guidelines for the preparation of conformity clauses in programming language

standards

ISO/IEC/TR 10176:2003, Information technology — Guidelines for the preparation of programming

language standards

ISO/IEC/TR 10182:—, Information technology — Programming languages, their environments and system

software interfaces — Guidelines for language bindings

ISO/IEC 10967-1:2012, Information technology — Language independent arithmetic — Part 1: Integer and

floating point arithmetic

ISO/IEC 11404:2007, Information technology — Programming languages, their environments and system

software interfaces — Language-independent datatypes

ISO/IEC 11578:1996, Information technology — Open Systems Interconnection — Remote Procedure Call

(RPC)

1) Withdrawn.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved 1

ISO/IEC 13719:1998, Information technology — Portable Common Tools Environment (PCTE)

ISO/IEC 13817-1:1996, Information technology — Programming languages, their environments and system

software interfaces — Vienna Development Method — Specification Language – Part 1: Base language

ISO/IEC 13886:1996, Information technology — Language-Independent Procedure Calling (LIPC)

ISO/IEC 14977:1996, Information technology — Syntactic metalanguage — Extended BNF

3 Terms, definitions and abbreviations

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

3.1 Definitions

3.1.1

client

see service user

3.1.2

datatype

set of values, usually accompanied by a set of operations on those values

3.1.3

formal language

formal specification language

see specification language

3.1.4

interface

mechanism by which a service user invokes and makes use of a service

3.1.5

language

unless otherwise qualified, “language” means “programming language”, not “specification language” or

“natural (human) language”

3.1.6

language binding

specification of the standard interface to a service, or set of services, for applications written in a

particular programming language

3.1.7

language-dependent

making use of the concepts, features or assumptions of a particular programming language

3.1.8

language-independent

not making use of the concepts, features or assumptions of any particular programming language or

style of language

3.1.9

language processor

entire computing system which enables a programming language user to translate and execute programs

written in the language, in general consisting both of hardware and of the relevant associated software

Note 1 to entry: This definition comes from ISO/IEC/TR 10176, Guidelines for the preparation of programming

language standards.

2 © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

3.1.10.1

mapping

(noun) defined association between elements (such as concepts, features or facilities) of one entity (such

as a programming language, or a specification, or a standard) with corresponding elements of another

entity

Note 1 to entry: Mappings are usually defined as being from one entity into another. A language binding of a

language L into a standard S usually incorporates both a mapping from L into S and a mapping from S into L.

3.1.10.2

mapping

(verb) process of determining or utilizing a mapping

Note 1 to entry: Depending upon what is being mapped, a mapping is not necessarily one-to-one. This means that

mapping an element E from system A into an element E’ of system B, followed by mapping E’ back into system A,

may not necessarily get back to the original E. In such situations, if a two-way correspondence is to be preserved,

execution of the mappings must include recording the place of origin and returning to it.

3.1.11

marshalling

process of collecting the actual parameters used in a procedure call, converting them if necessary, and

assembling them for transfer to the called procedure

Note 1 to entry: This process is also carried out by the called procedure when preparing to return the results of

the call to the caller

Note 2 to entry: Marshalling can be regarded as being performed by a service user when preparing input values

for a service provider, and by a service provider when preparing results for a service user, the service concerned

being regarded as the procedure being called.

3.1.12

procedure

subprogram which may or may not return a value (the former variant is sometimes called a subroutine,

the latter is sometimes called a function)

Note 1 to entry: Some programming languages use different terminology.

3.1.13

server

see service provider

3.1.14

service

facility or set of facilities made available to service users through an interface

3.1.15

service provider

computer system or set of computer systems that implements a service and makes it available to service

uers

Note 1 to entry: In this definition, “computer system” means a logical system, not a physical system; it may

correspond to part of all of one or more physical computer systems.

Note 2 to entry: The term “server” is often used in a similar sense, though sometimes implying a physical computer

system that has no other function than to provide its service

3.1.16

service user

application (typically a program in some language) which makes use of a service

Note 1 to entry: The term “client” is often used in a similar sense, though sometimes implying the physical

computer system on which the application is running, rather than just the application itself.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved 3

3.1.17

specification language

formal language for defining the semantics of a service or an interface precisely and without ambiguity

3.1.18

unmarshalling

process of receiving and disassembling transferred parameters, and converting them if necessary, to

prepare the values for further use

Note 1 to entry: This process is carried out by the called procedure on receipt of the actual parameters for the call,

and by the caller on receipt of the returned results of the call

Note 2 to entry: Unmarshalling can be regarded as being performed by a service provider when receiving input

values from a service user, and by a service user when receiving results from a service provider, the service

concerned being regarded as the procedure being called.

3.1.19.1

Z

e.g. ISO/IEC 10967-1:2012) the complex numbers

3.1.19.2

Z

formal specification language, see ISO/IEC WD 13568

3.2 Abbreviations

3.2.1

LID

language-independent datatypes, as defined in ISO/IEC 11404:2007

3.2.2

LIPC

language-Independent Procedure Calling, as defined in ISO/IEC 13886:1996

3.2.3

RPC

remote Procedure Call, as defined in ISO/IEC 11578:1996

4 Overview

4.1 Services, interfaces, service providers and service users

The concept of a “service” is a very general one. In some contexts it is customary to use it in a restricted

sense, e.g. when talking about “service industries” as contrasted with “manufacturing industries”.

Despite such usages, almost any activity or behaviour can be regarded as a “service”, if it serves some

useful purpose to do so (for example, manufacturing spoons can be regarded as a service for those

needing spoons).

With the concept of a service come the concepts of a “service provider” and a “service user”. The

provider performs the activity that constitutes the service; the user is the customer or the client for

the service, for whom the service is performed. In the information technology field, the “client-server

model” incorporates these concepts: the server provides, the client uses.

Between the service provider and the service user is an interface that allows them to communicate.

The service user communicates through the interface the requirement for the service, and any relevant

information (e.g. not only the need for spoons, but the number and size of spoons required), and the

service provider communicates through the interface the response to the order for the service, and any

additional information or queries (e.g. the spoons can be delivered in six days, do you want silver spoons

or plastic spoons?). In the information technology field, such interfaces are usually explicit, realized

4 © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

in hardware or software or both. In the world in general, they are sometimes explicit, but sometimes

subsumed in more general human or other interactions.

This distinction between provider and user (client and server) must not be assumed to correspond to

identifiable distinct entities. The distinction, and the service interface, may be purely notional, and

possibly not normally thought of in that way. The service itself may similarly not correspond to a distinct,

separate activity, and again possibly not normally thought of as such; it may be subsumed in some other

activity or group of activities, and may possibly be implicit.

Hence, for example, in a transaction between two parties, each one may be providing a service for the

other: each is a client, and each a server. In another context, the provider is providing the service to

itself; the provider is also the user. Though it may be possible to subdivide the provider/user into a

provider part and a user part when considering provision of the service, this may be inconvenient in

other respects.

In summary, “client” and “server”, are roles that are carried out, rather than elements that necessarily

must be implemented separately. Though the term “client-server” is sometimes used in the information

technology field in ways that are more specific than it is used here, it is important not to carry over

assumptions from particular client-server models when reading this Technical Report. It is still more

important not to assume that implementation of any service, in the sense used here, has to be done using

a client-server model.

4.2 Information technology services

The history of information technology has many instances of the technology, or a product, being used for

very different purposes and in very different ways from those originally envisaged. The kinds of service

that information technology and products provide have continually expanded and diversified, and this

is still continuing.

It is as common in information technology as in the outside world for the term “service” in particular

contexts to be used in a rather specific way. The history of the technology suggests that, for the purposes

of formulating guidelines about services, the term should instead be used as generally as possible.

This Technical Report has adopted this very general approach to the concept of “service”. It is therefore

important that, when using this Technical Report and the guidelines it contains, no presuppositions

should be made about what a service is, or about how and by what it is provided or how and by what it is

used. The guidelines should be interpreted and applied in that light.

This Technical Report does, however, carefully distinguish between the service itself, and the interface

used to communicate with it. In some usages the term “service” includes the interface, and the interface

may be embedded in the service and its specification (as in the phrase “all parts of the service”). However,

logically they are distinct, and this logical distinction is maintained throughout this Technical Report.

Services in the most general sense often simply evolve naturally, but information technology services

are usually consciously designed. They are also often built from explicit specifications, though some are

developed ad hoc. Whichever the case, it is useful to make a clear logical distinction between service

providers, service users, and the interface between them, even if, when implemented, one or both of these

distinctions will be purely notional, and will not be embodied in identifiable and separable artefacts like

particular hardware components or particular blocks of code. Indeed, thinking about service provision

in such a way, in an environment that is normally regarded as a more integrated whole, can help to

improve a specification, or at least to test it and verify its validity.

This is especially so in the increasing number of cases where information technology environments and

services, though originally conceived as self-contained, have to interact with external environments

and services, many of which will need the distinction between providers and users to be made explicit.

An instance of direct relevance to this Technical Report is where interacting entities are based upon

different languages and hence different sets of underlying assumptions.

© ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved 5

4.3 Services and language independence

The term “language-independent service (or interface) specification” means “language-independent

specification of a service (or interface)”, not “specification of a language-independent service (or

interface)”. Hence a language-independent specification of a service does not imply that the service itself

is “language independent” in the sense intended here. The service specified may be relevant only to

environments of particular languages.

NOTE 1 The implementation of a service which meets the specification will use some language or other, if only

machine language, and so will in a sense be “dependent” on that language, but that is not the sense intended here.

Also, a language-independent specification of an interface does not imply that the service interfaced to

is either itself “language independent”, or specified in a language-independent way (though it may be).

A trivial instance is that of a language processor for a particular language providing a service by

executing a program in that language. For one of the long-established languages (like Cobol or Fortran)

the interface is the provision of input data and the output of results. The language was designed for

particular forms of input and output media, presumed under the control of a human user. However, a

language-independent interface specification could define the input and output in such a way that the

data can come from, and the results be returned to, some other system, in general using a different

language.

In a simple case like that, the user system and the interface are distinct and not closely coupled. The

interface can be implemented as a “black box” which acts in the same way that a human interpreter

would for two people with different languages conversing: it takes input from the client and translates it

into the equivalent input for the service, and takes the output from the service and translates it into the

equivalent output for the client.

In the more general case the interface might need to be embedded in the client system so that it appears

to be integrated in that host environment. That environment may require invocations of the service

to be expressed in more meaningful terms, not limited to the data transmitted to it and the results

expected from it.

NOTE 2 One example involves the functional standards for graphics. In some languages the most suitable

invocation method is a procedure call to an external library, while in others the most suitable method is the use

of additional commands (keywords).

Both the simple and the general case are referred to as “binding” to the interface, though the binding is

much tighter in the general case. A “language binding” to the interface binds a particular programming

language (in general not the same programming language as the one used by the server), so that

programs written in that language can have access to the service. A good language binding allows

language users to use a style of accessing the service which is familiar to them, and will also accord with

official standards for the language.

ISO/IEC/TR 10182, Guidelines for language bindings, provides guidance to those performing language

bindings and writing standards for them. This Technical Report provides complementary guidance to

those specifying service interfaces in a language-independent way, and writing standards for them.

A useful way of looking at language independence is by considering levels of abstraction. The various

elements of programming languages can be regarded as existing at three levels of abstraction: abstract,

computational, or representational, where the middle, computational level can be divided into two

sublevels, linguistic and operational. The linguistic elements are regarded as instantiations at the

computational level of the abstract concepts, while the operational level deals with manipulation of the

elements, which inevitably looks “downwards” to the realization of the elements in actual, processible

entities at the representational level.

NOTE 3 The representational level does not necessarily mean the physical hardware level, or the logical level

of bits and bytes; see the discussion in 4.5.1 below.

6 © ISO/IEC 2014 – All rights reserved

4.4 Language-independent specifications

As the preceding discussion has shown, a language-independent specification may be a service

specification, specifying the service itself, or be an interface specification, specifying how the service is

accessed by clients. It may of course cover both.

This Technical Report is concerned primarily with specification of the interface to the service, rather

than of the service itself. The service may be predefined in a language-dependent way. How a service

is specified is likely to depend to some extent on the nature of the service and its application area,

so guidelines on specification of the service are definitely outside the scope of this Technical Report.

However, where it is wished to produce a language-independent specification of a service, so that it can

be implemented in a variety of different languages, then the guidelines presented may be useful, directly

or indirectly. For example, they may draw attention to factors that should be borne in mind, and it may

then be possible to adapt them to the particular circumstances.

This Technical Report therefore provides guidelines applicable in the following cases:

— specification of a service interface;

— specification both of a service interface and of the corresponding service itself, together;

— specifying from scratch (i.e. without anything pre-existing to base it on);

— specifying on the basis of an existing (probably language-dependent) service;

— specifying on the basis of an existing (language-dependent) binding.

Guidelines are grouped under various headings, dealing with different aspects. As far as possible each

group is independent, in the sense that they can be referred to without necessarily working through

preceding groups. Any necessary cross-references are provided.

4.5 Problems of language dependence and inbuilt assumptions

Producing a language-independent specification can present many problems, especially if starting from

an existing service which was not originally designed to be language independent - typically, a service

designed in and for a particular language environment. If a service is specified in the “wrong” way - it may

of course not have been “wrong” in its original context - it can make producing a language-independent

interface very difficult. In particular, it may depend on explicit or (more likely) implicit assumptions

about the lang

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...