ISO/IEC TS 17961:2013

(Main)Information technology — Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces — C secure coding rules

Information technology — Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces — C secure coding rules

ISO/IEC TS 17961:2013 specifies rules for secure coding in the C programming language, and code examples. ISO/IEC TS 17961:2013 does not specify the mechanism by which these rules are enforced, or any particular coding style to be enforced. Each rule in this Technical Specification is accompanied by code examples. Two distinct kinds of examples are provided: noncompliant examples demonstrating language constructs that have weaknesses with potentially exploitable security implications; such examples are expected to elicit a diagnostic from a conforming analyzer for the affected language construct; and compliant examples are expected not to elicit a diagnostic.

Technologies de l'information — Langages de programmation, leur environnement et interfaces des logiciels de systèmes — Règles de programmation sécurisée en C

General Information

Standards Content (Sample)

TECHNICAL ISO/IEC

SPECIFICATION TS

First edition

2013-11-15

Information technology —

Programming languages, their

environments and system software

interfaces — C secure coding rules

Technologies de l’information — Langages de programmation, leur

environnement et interfaces des logiciels de systèmes — Règles de

programmation sécurisée en C

Reference number

©

ISO/IEC 2013

© ISO/IEC 2013

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior

written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of

the requester.

ISO copyright office

Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20

Tel. + 41 22 749 01 11

Fax + 41 22 749 09 47

E-mail copyright@iso.org

Web www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction .vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Conformance . 1

2.1 Portability assumptions . 2

3 Normative references . 2

4 Terms and definitions . 2

5 Rules . 5

5.1 Accessing an object through a pointer to an incompatible type [ptrcomp] . 5

5.2 Accessing freed memory [accfree] . 6

5.3 Accessing shared objects in signal handlers [accsig] . 7

5.4 No assignment in conditional expressions [boolasgn] . 8

5.5 Calling functions in the C Standard Library other than abort, _Exit, and signal

from within a signal handler [asyncsig] . 9

5.6 Calling functions with incorrect arguments [argcomp] .11

5.7 Calling signal from interruptible signal handlers [sigcall] .12

5.8 Calling system [syscall] .13

5.9 Comparison of padding data [padcomp] .14

5.10 Converting a pointer to integer or integer to pointer [intptrconv] .14

5.11 Converting pointer values to more strictly aligned pointer types [alignconv] .15

5.12 Copying a FILE object [filecpy] .16

5.13 Declaring the same function or object in incompatible ways [funcdecl] .16

5.14 Dereferencing an out-of-domain pointer [nullref] .18

5.15 Escaping of the address of an automatic object [addrescape] .18

5.16 Conversion of signed characters to wider integer types before a check for

EOF [signconv] .19

5.17 Use of an implied default in a switch statement [swtchdflt] .19

5.18 Failing to close files or free dynamic memory when they are no longer needed

[fileclose] .20

5.19 Failing to detect and handle standard library errors [liberr] .20

5.20 Forming invalid pointers by library function [libptr] .26

5.21 Allocating insufficient memory [insufmem].28

5.22 Forming or using out-of-bounds pointers or array subscripts [invptr] .29

5.23 Freeing memory multiple times [dblfree] .34

5.24 Including tainted or out-of-domain input in a format string [usrfmt].35

5.25 Incorrectly setting and using errno [inverrno] .37

5.26 Integer division errors [diverr] .39

5.27 Interleaving stream inputs and outputs without a flush or positioning call [ioileave] .40

5.28 Modifying string literals [strmod] .41

5.29 Modifying the string returned by getenv, localeconv, setlocale, and

strerror [libmod] .42

5.30 Overflowing signed integers [intoflow] .43

5.31 Passing a non-null-terminated character sequence to a library function that expects

a string [nonnullcs] .44

5.32 Passing arguments to character-handling functions that are not representable as

unsigned char [chrsgnext] .45

5.33 Passing pointers into the same object as arguments to different restrict-qualified

parameters [restrict] .46

5.34 Reallocating or freeing memory that was not dynamically allocated [xfree] .47

5.35 Referencing uninitialized memory [uninitref] .48

5.36 Subtracting or comparing two pointers that do not refer to the same array [ptrobj] .49

5.37 Tainted strings are passed to a string copying function [taintstrcpy] .50

© ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved iii

5.38 Taking the size of a pointer to determine the size of the pointed-to type [sizeofptr] .50

5.39 Using a tainted value as an argument to an unprototyped function

pointer [taintnoproto] .51

5.40 Using a tainted value to write to an object using a formatted input or output

function [taintformatio] .52

5.41 Using a value for fsetpos other than a value returned from fgetpos [xfilepos] .52

5.42 Using an object overwritten by getenv, localeconv, setlocale, and

strerror [libuse] .53

5.43 Using character values that are indistinguishable from EOF [chreof] .54

5.44 Using identifiers that are reserved for the implementation [resident] .55

5.45 Using invalid format strings [invfmtstr] .57

5.46 Tainted, potentially mutilated, or out-of-domain integer values are used in a restricted

sink [taintsink] .58

Annex A (informative) Intra- to Interprocedural Transformations .59

Annex B (informative) Undefined Behavior .63

Annex C (informative) Related Guidelines and References .71

Annex D (informative) Decidability of Rules .77

Bibliography .78

iv © ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) and IEC (the International Electrotechnical

Commission) form the specialized system for worldwide standardization. National bodies that are

members of ISO or IEC participate in the development of International Standards through technical

committees established by the respective organization to deal with particular fields of technical

activity. ISO and IEC technical committees collaborate in fields of mutual interest. Other international

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO and IEC, also take part in the

work. In the field of information technology, ISO and IEC have established a joint technical committee,

ISO/IEC JTC 1.

International Standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2.

The main task of the joint technical committee is to prepare International Standards. Draft International

Standards adopted by the joint technical committee are circulated to national bodies for voting.

Publication as an International Standard requires approval by at least 75 % of the national bodies

casting a vote.

In other circumstances, particularly when there is an urgent market requirement for such documents,

the joint technical committee may decide to publish an ISO/IEC Technical Specification (ISO/IEC TS),

which represents an agreement between the members of the joint technical committee and is accepted

for publication if it is approved by 2/3 of the members of the committee casting a vote.

An ISO/IEC TS is reviewed after three years in order to decide whether it will be confirmed for a further

three years, revised to become an International Standard, or withdrawn. If the ISO/IEC TS is confirmed,

it is reviewed again after a further three years, at which time it must either be transformed into an

International Standard or be withdrawn.

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

ISO/IEC TS 17961 was prepared by Joint Technical Committee ISO/IEC JTC 1, Information technology,

Subcommittee SC 22, Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces.

© ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved v

Introduction

Background

An essential element of secure coding in the C programming language is a set of well-documented and

enforceable coding rules. The rules specified in this Technical Specification apply to analyzers, including

static analysis tools and C language compiler vendors that wish to diagnose insecure code beyond the

requirements of the language standard. All rules are meant to be enforceable by static analysis.

The application of static analysis to security has been done in an ad hoc manner by different vendors,

resulting in nonuniform coverage of significant security issues. This specification enumerates

secure coding rules and requires analysis engines to diagnose violations of these rules as a matter

of conformance to this specification. These rules may be extended in an implementation-dependent

manner, which provides a minimum coverage guarantee to customers of any and all conforming static

analysis implementations.

The largest underserved market in security is ordinary, non-security-critical code. The security-critical

nature of code depends on its purpose rather than its environment. The UNIX finger daemon (fingerd)

is an example of ordinary code, even though it may be deployed in a hostile environment. A user runs the

client program, finger, which sends a user name to fingerd over the network, which then sends a reply

indicating whether the user is logged in and a few other pieces of information. The function of fingerd

has nothing to do with security. However, in 1988, Robert Morris compromised fingerd by triggering a

buffer overflow, allowing him to execute arbitrary code on the target machine. The Morris worm could

have been prevented from using fingerd as an attack vector by preventing buffer overflows, regardless

of whether fingerd contained other types of bugs.

By contrast, the function of /bin/login is purely related to security. A bug of any kind in /bin/login

has the potential to allow access where it was not intended. This is security-critical code.

Similarly, in safety-critical code, such as software that runs an X-ray machine, any bug at all could

have serious consequences. In practice, then, security-critical and safety-critical code have the same

requirements.

There are already standards that address safety-critical code and therefore security-critical code. The

problem is that because they must focus on preventing essentially all bugs, they are required to be

so strict that most people outside the safety-critical community do not want to use them. This leaves

ordinary code like fingerd unprotected.

This Technical Specification has two major subdivisions:

— preliminary elements (Clauses 1–4) and

— secure coding rules (Clause 5).

Each secure coding rule in Clause 5 has a separate numbered subsection and a unique section identifier

enclosed in brackets (for example, [ptrcomp]). The unique section identifiers are mainly for use by

other documents in identifying the rules should the section numbers change because of the addition or

elimination of a rule. These identifiers may be used in diagnostics issued by conforming analyzers, but

analyzers are not required to do so.

Annexes provide additional information. Annex C (informative) Related Guidelines and References

identifies related guidelines and references per rule. A bibliography lists documents referred to during

the preparation of this Technical Specification.

The rules documented in this Technical Specification do not rely on source code annotations or assumptions

of programmer intent. However, a conforming implementation may take advantage of annotations to

inform the analyzer. The rules, as specified, are reasonably simple, although complications can exist

in identifying exceptions. An analyzer that conforms to this Technical Specification should be able to

analyze code without excessive false positives, even if the code was developed without the expectation

that it would be analyzed. Many analyzers provide methods that eliminate the need to research each

vi © ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved

diagnostic on every invocation of the analyzer. The implementation of such a mechanism is encouraged

but not required. This Technical Specification assumes that an analyzer’s visibility extends beyond the

boundaries of the current function or translation unit being analyzed (see Annex A (informative) Intra-

to Interprocedural Transformations).

Completeness and soundness

The rules specified in this Technical Specification are designed to provide a check against a set of

programming flaws that are known from practical experience to have led to vulnerabilities. Although

rule checking can be performed manually, with increasing program complexity, it rapidly becomes

infeasible. For this reason, the use of static analysis tools is recommended.

It should be recognized that, in general, determining conformance to coding rules is computationally

undecidable. The precision of static analysis has practical limitations. For example, the halting

theorem of Computer Science states that there are programs whose exact control flow cannot be

determined statically. Consequently, any property dependent on control flow—such as halting—may

be indeterminate for some programs. A consequence of this undecidability is that it may be impossible

for any tool to determine statically whether a given rule is satisfied in specific circumstances. The

widespread presence of such code may also lead to unexpected results from an analysis tool. Annex D

(informative) Decidability of Rules provides information on the decidability of rules in this Technical

Specification.

However checking is performed, the analysis may generate

— false negatives: Failure to report a real flaw in the code is usually regarded as the most serious

analysis error, as it may leave the user with a false sense of security. Most tools err on the side of

caution and consequently generate false positives. However, there may be cases where it is deemed

better to report some high-risk flaws and miss others than to overwhelm the user with false positives.

— false positives: The tool reports a flaw when one does not exist. False positives may occur because

the code is sufficiently complex that the tool cannot perform a complete analysis. The use of features

such as function pointers and libraries may make false positives more likely.

To the greatest extent feasible, an analyzer should be both complete and sound with respect to

enforceable rules. An analyzer is considered sound with respect to a specific rule if it cannot give a

false-negative result, meaning it finds all violations of a rule within the entire program. An analyzer is

considered complete if it cannot issue false-positive results, or false alarms. The possibilities for a given

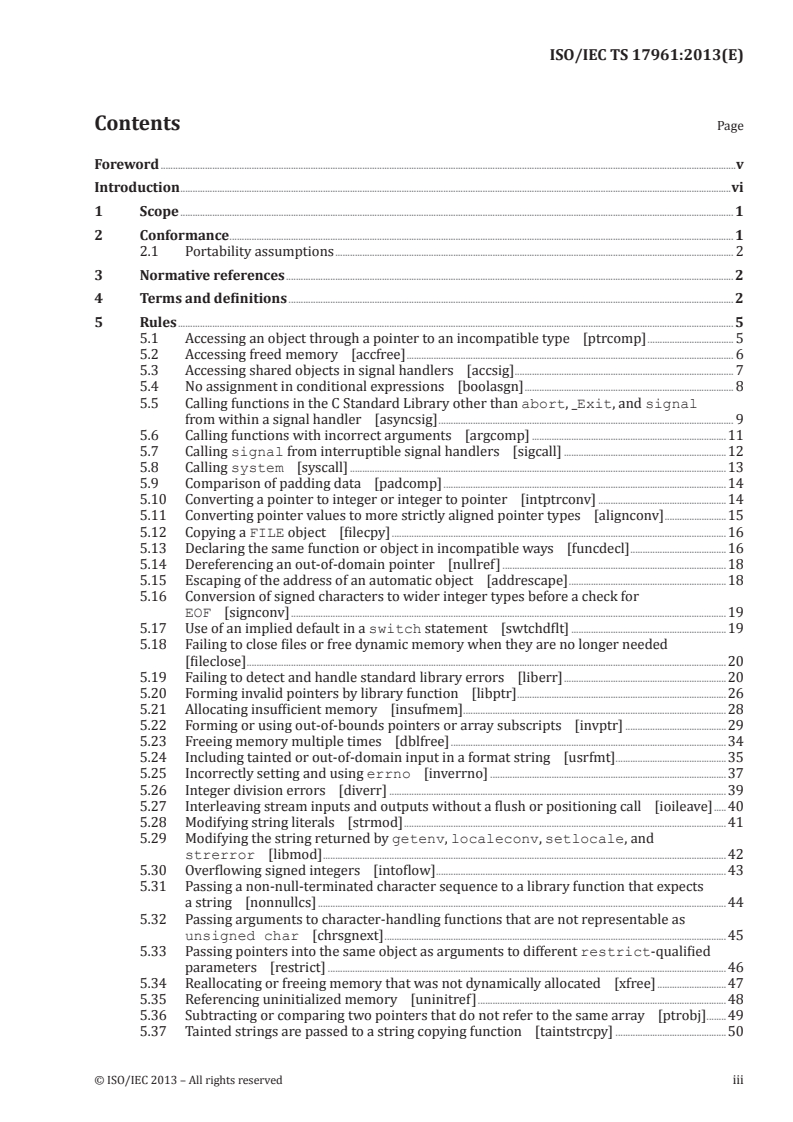

rule are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 — Completeness and soundness

False positives

Y N

Sound with Complete and

False N

false positives sound

negatives

Unsound with Complete and

Y

false positives unsound

The degree to which conforming analyzers minimize false-positive diagnostics is a quality of

implementation issue. In other words, quantitative thresholds for false positives and false negatives are

outside the scope of this Technical Specification.

Security focus

The purpose of this Technical Specification is to specify analyzable secure coding rules that can be

automatically enforced to detect security flaws in C-conforming applications. To be considered a security

flaw, a software bug must be triggerable by the actions of a malicious user or attacker. An attacker

may trigger a bug by providing malicious data or by providing inputs that execute a particular control

© ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved vii

path that in turn executes the security flaw. Implementers are encouraged to distinguish violations that

operate on untrusted data from those that do not.

Taint analysis

Taint and tainted sources

Certain operations and functions have a domain that is a subset of the type domain of their operands

or parameters. When the actual values are outside of the defined domain, the result might be either

undefined or at least unexpected. If the value of an operand or argument may be outside the domain

of an operation or function that consumes that value, and the value is derived from any external input

to the program (such as a command-line argument, data returned from a system call, or data in shared

memory), that value is tainted, and its origin is known as a tainted source. A tainted value is not necessarily

known to be out of the domain; rather, it is not known to be in the domain. Only values, and not the

operands or arguments, can be tainted; in some cases, the same operand or argument can hold tainted

or untainted values along different paths. In this regard, taint is an attribute of a value originating from

a tainted source.

Restricted sinks

Operands and arguments whose domain is a subset of the domain described by their types are called

restricted sinks. Any pointer arithmetic operation involving an integer operand is a restricted sink

for that operand. Certain parameters of certain library functions are restricted sinks because these

functions perform address arithmetic with these parameters, or control the allocation of a resource, or

pass these parameters on to another restricted sink. All string input parameters to library functions are

restricted sinks because it is possible to pass in a character sequence that is not null terminated. The

exceptions are strncpy and strncpy_s, which explicitly allow the source character sequence not to

be null-terminated. For purposes of this Technical Specification, we regard char * as a reference to a

null-terminated array of characters.

Propagation

Taint is propagated through operations from operands to results unless the operation itself imposes

constraints on the value of its result that subsume the constraints imposed by restricted sinks. In

addition to operations that propagate the same sort of taint, there are operations that propagate taint

of one sort of an operand to taint of a different sort for their results, the most notable example of which

is strlen propagating the taint of its argument with respect to string length to the taint of its return

value with respect to range.

Although the exit condition of a loop is not normally itself considered to be a restricted sink, a loop

whose exit condition depends on a tainted value propagates taint to any numeric or pointer variables

that are increased or decreased by amounts proportional to the number of iterations of the loop.

Sanitization

To remove the taint from a value, it must be sanitized to ensure that it is in the defined domain of

any restricted sink into which it flows. Sanitization is performed by replacement or termination. In

replacement, out-of-domain values are replaced by in-domain values, and processing continues using

an in-domain value in place of the original. In termination, the program logic terminates the path of

execution when an out-of-domain value is detected, often simply by branching around whatever code

would have used the value.

In general, sanitization cannot be recognized exactly using static analysis. Analyzers that perform taint

analysis usually provide some extralinguistic mechanism to identify sanitizing functions that sanitize an

argument (passed by address) in place, return a sanitized version of an argument, or return a status code

indicating whether the argument is in the required domain. Because such extralinguistic mechanisms

are outside the scope of this specification, this Technical Specification uses a set of rudimentary

definitions of sanitization that is likely to recognize real sanitization but might cause nonsanitizing or

ineffectively sanitizing code to be misconstrued as sanitizing. The following definition of sanitization

presupposes that the analysis is in some way maintaining a set of constraints on each value encountered

as the simulated execution progresses: a given path through the code sanitizes a value with respect to a

viii © ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved

given restricted sink if it restricts the range of that value to a subset of the defined domain of the restricted

sink type. For example, sanitization of signed integers with respect to an array index operation must

restrict the range of that integer value to numbers between zero and the size of the array minus one.

This description is suitable for numeric values, but sanitization of strings with respect to content is

more difficult to recognize in a general way.

Tainted source macros

The function-like macros GET_TAINTED_STRING and GET_TAINTED_INTEGER defined in this

section are used in the examples in this Technical Specification to represent one possible method to

obtain a tainted string and tainted integer.

#define GET_TAINTED_STRING(buf, buf_size) \

do { \

const char *taint = getenv(“TAINT”); \

if (taint == 0) { \

exit(1); \

} \

\

size_t taint_size = strlen(taint) + 1; \

if (taint_size > buf_size) { \

exit(1); \

} \

\

strncpy(buf, taint, taint_size); \

} while (0)

#define GET_TAINTED_INTEGER(type, val) \

do { \

const char *taint = getenv(“TAINT”); \

if (taint == 0) { \

exit(1); \

} \

\

errno = 0; \

long tmp = strtol(taint, 0, 10); \

if ((tmp == LONG_MIN || tmp == LONG_MAX) && \

errno == ERANGE) \

; /* retain LONG_MIN or LONG_MAX */ \

if ((type)-1 < 0) { \

if (tmp < INT_MIN) \

tmp = INT_MIN; \

else if (tmp > INT_MAX) \

tmp = INT_MAX; \

} \

val = tmp; \

} while (0)

© ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved ix

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION ISO/IEC TS 17961:2013(E)

Information technology — Programming languages,

their environments and system software interfaces — C

secure coding rules

1 Scope

This Technical Specification specifies

— rules for secure coding in the C programming language and

— code examples.

This Technical Specification does not specify

— the mechanism by which these rules are enforced or

— any particular coding style to be enforced. (It has been impossible to develop a consensus on

appropriate style guidelines. Programmers should define style guidelines and apply these guidelines

consistently. The easiest way to consistently apply a coding style is with the use of a code formatting

tool. Many interactive development environments provide such capabilities.)

Each rule in this Technical Specification is accompanied by code examples. Code examples are

informative only and serve to clarify the requirements outlined in the normative portion of the rule.

Examples impose no normative requirements.

Each rule in this Technical Specification that is based on undefined behavior defined in the C Standard

identifies the undefined behavior by a numeric code. The numeric codes for undefined behaviors can be

found in Annex B, Undefined Behavior.

Two distinct kinds of examples are provided:

— noncompliant examples demonstrating language constructs that have weaknesses with potentially

exploitable security implications; such examples are expected to elicit a diagnostic from a conforming

analyzer for the affected language construct; and

— compliant examples are expected not to elicit a diagnostic.

Examples are not intended to be complete programs. For brevity, they typically omit #include

directives of C Standard Library headers that would otherwise be necessary to provide declarations of

referenced symbols. Code examples may also declare symbols without providing their definitions if the

definitions are not essential for demonstrating a specific weakness.

Some rules in this Technical Specification have exceptions. Exceptions are part of the specification of

these rules and are normative.

2 Conformance

In this Technical Specification, “shall” is to be interpreted as a requirement on an analyzer; conversely,

“shall not” is to be interpreted as a prohibition.

Various types of programs (such as compilers or specialized analyzers) can be used to check if a program

contains any violations of the coding rules specified in this Technical Specification. In this Technical

Specification, all such checking programs are called analyzers. An analyzer can claim conformity with

this Technical Specification. Programs that do not yield any diagnostic when analyzed by a conforming

analyzer cannot claim conformity to this Technical Specification.

© ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved 1

A conforming analyzer shall produce a diagnostic for each distinct rule in this Technical Specification

upon detecting a violation of that rule, except in the case that the same program text violates multiple

rules simultaneously, where a conforming analyzer may aggregate diagnostics but shall produce at least

one diagnostic.

NOTE 1 The diagnostic message might be of the form:

Accessing freed memory in function abc, file xyz.c, line nnn.

NOTE 2 This Technical Specification does not require an analyzer to produce a diagnostic message for any

violation of any syntax rule or constraint specified by the C Standard.

Conformance is defined only with respect to source code that is visible to the analyzer. Binary-only

libraries, and calls to them, are outside the scope of these rules.

For each rule, the analyzer shall report a diagnostic for at least one program that contains a violation

of that rule.

For each rule, the analyzer shall document whether its analysis is guaranteed to report all violations of

that rule and shall document its accuracy with respect to avoiding false positives and false negatives.

2.1 Portability assumptions

A conforming analyzer shall be able to diagnose violations of guidelines for at least one C implementation.

An analyzer need not diagnose a rule violation if the result is documented for the target implementation and

does not cause a security flaw. A conforming analyzer shall document which C implementation is the target.

Variations in quality of implementation permit an analyzer to produce diagnostics concerning

portability issues.

EXAMPLE

long i;

printf(“i = %d”, i);

This example can produce a diagnostic, such as the mismatch between %d and long int. This Technical

Specification does not specify that a conforming analyzer be complete or sound when diagnosing rule

violations. This mismatch might not be a problem for all target implementations, but it is a portability

problem because not all implementations have the same representation for int and long.

3 Normative references

The following documents, in whole or in part, are normatively referenced in this document and are

indispensable for its application. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For undated

references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO/IEC 9899:2011, Information technology — Programming languages — C

ISO 80000-2:2009, Quantities and units — Part 2: Mathematical signs and symbols to be used in the natural

sciences and technology

ISO/IEC 2382-1:1993, Information technology — Vocabulary — Part 1: Fundamental terms

ISO/IEC/IEEE 9945:2009, Information technology — Portable Operating System Interface (POSIX®) Base

Specifications, Issue 7

4 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions given in ISO/IEC 9899:2011, ISO/IEC 2382-

1:1993 and the following apply. Other terms are defined where they appear in italic type. Mathematical

symbols not defined in this document are to be interpreted according to ISO 80000-2:2009.

2 © ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved

4.1

analyzer

mechanism that diagnoses coding flaws in software programs

Note 1 to entry: Analyzers may include static analysis tools, tools within a compiler suite, or tools in other contexts.

4.2

data flow analysis

tracking of value constraints along nonexcluded paths through the code

Note 1 to entry: Tracking can be performed intraprocedurally, with various assumptions made about what happens

at function call boundaries, or interprocedurally, where values are tracked flowing into function calls (directly or

indirectly) as arguments and flowing back out either as return values or indirectly through arguments.

Note 2 to entry: Data flow analysis may or may not track values flowing into or out of the heap or take into

account global variables. When this specification refers to values flowing, the key point is contrast with variables

or expressions, because a given variable or expression may hold different values along different paths, and a given

value may be held by multiple variables or expressions along a path.

4.3

exploit

technique that takes advantage of a security vulnerability to violate an explicit or implicit security policy

4.4

in-band error indicator

library function return value on error that can never be returned by a successful call to that library function

4.5

mutilated value

result of an operation performed on an untainted value that yields either an undefined result (such as the

result of signed integer overflow), the result of right-shifting a negative number, implicit conversion to an

integral type where the value cannot be represented in the destination type, or unsigned integer wrapping

EXAMPLE

int j = INT_MAX + 1; // j is mutilated

char c = 1234; // c is mutilated if char is eight bits

unsigned int u = 0U - 1; // u is mutilated

Note 1 to entry: A mutilated value can be just as dangerous as a tainted value because it can differ either in sign

or magnitude from what the programmer expects.

4.6

nonpersistent signal handler

signal handler running on an implementation that requires the program to again register the signal

handler after occurrences of the signal to catch subsequent occurrences of that signal

4.7

out-of-band error indicator

library function return value used to indicate nothing but the error status

4.8

out-of-domain value

one of a set of values that is not in the domain of a particular operator or function

4.9

restricted sink

operands and arguments whose domain is a subset of the domain described by their types

Note 1 to entry: Undefined or unexpected behavior may occur if a tainted value is supplied as a value to a

restricted sink.

Note 2 to entry: A diagnostic is required if a tainted value is supplied to a restricted sink.

© ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved 3

Note 3 to entry: Different restricted sinks may impose different validity constraints for the same value; a given

value can be tainted with respect to one restricted sink but sanitized (and consequently no longer tainted) with

respect to a different restricted sink.

Note 4 to entry: Specific restricted sinks and requirements for sanitizing tainted values are described in specific

rules dealing with taint analysis (see 5.8, 5.14, 5.24, 5.30, 5.39, and 5.46).

4.10

sanitize

assure by testing or replacement that a tainted or other value conforms to the constraints imposed by

one or more restricted sinks into which it may flow

Note 1 to entry: If the value does not conform, either the path is diverted to avoid using the value or a different,

known-conforming value is substituted.

EXAMPLE Adding a null character to the end of a buffer before passing it as an argument to the strlen function.

4.11

security flaw

defect that poses a potential security risk

4.12

security policy

set of rules and practices that specify or regulate how a system or organization provides security

services to protect sensitive and critical system resources

4.13

static analysis

any process for assessing code without executing it

[1]

Note 1 to entry: See , p. 3.

4.14

tainted source

external source of untrusted data

Note 1 to entry: Tainted sources include

— parameters to the main function,

— the returned values from localeconv, fgetc, getc, getchar, fgetwc, getwc, and getwchar, and

— the strings produced by getenv, fscanf, vfscanf, vscanf, fgets, fread, fwscanf, vfwscanf,

vwscanf, wscanf, and fgetws.

4.15

tainted value

value derived from a tainted source that has not been sanitized

4.16

target implementation

implementation of the C programming language whose environmental limits and implementation-

defined behavior are assumed by the analyzer during the analysis of a program

4.17

UB

undefined behavior

4.18

unexpected behavior

well-defined behavior that may be unexpected or unanticipated by the programmer; incorrect

programming assumptions

4 © ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved

4.19

unsigned integer wrapping

computation involving unsigned operands whose result is reduced modulo the number that is one

greater than the largest value that can be represented by the resulting type

4.20

untrusted data

data originating from outside of a trust boundary

[2]

Note 1 to entry: See .

4.21

valid pointer

pointer that refers to an element within an array or one past the last element of an array

Note 1 to entry: For the purposes of this definition, a pointer to an object that is not an element of an array behaves

the same as a pointer to the first element of an array of length one with the type of the object as its element type.

(See ISO/IEC 9899:2011, 6.5.8, paragraph 4.)

Note 2 to entry: For the purposes of this definition, an object can be considered to be an array of a certain number

of bytes; that number is the size of the object, as produced by the sizeof operator. (See ISO/IEC 9899:2011,

6.3.2.3, paragraph 7.)

4.22

vulnerability

set of conditions that allows an attacker to violate an explicit or implicit security policy

5 Rules

5.1 Accessing an object through a pointer to an incompatible type [ptrcomp]

Rule

Accessing an object through a pointer to an incompatible type (other than unsigned char) shall

be diagnosed.

Rationale

ISO/IEC 9899:2011, 6.5, paragraph 7, states,

An object shall have its stored value accessed only by an lvalue expression that has one of the following types:

— a type compatible with the effective type of the object,

— a qualified version of a type compatible with the effective type of the object,

— a type that is the signed or unsigned type corresponding to the effective type of the object,

— a type that is the signed or unsigned type corresponding to a qualified version of the effective type

of the object,

— an aggregate or union type that includes one of the aforementioned types among its members

(including, recursively, a member of a subaggregate or contained union), or

— a character type.

The intent of this list is to specify those circumstances in which an object may or may not be aliased.

According to ISO/IEC 9899:2011, 6.2.6.1,

© ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved 5

Certain object representations need not represent a value of the object type. If the stored value of an

object has such a representation and is read by an lvalue expression that does not have character type,

the behavior is undefined.

Accessing an object through a pointer to an incompatible type (other than unsigned char) is

undefined behavior.

C identifies the following undefined behavior:

UB Description

37 An object has its stored value accessed other than by an lvalue of an allowable type (6.5).

Example(s)

EXAMPLE In this noncompliant example, a diagnostic is required because an object of type float is

incremented through a pointer to int, ip.

void f(void) {

if (sizeof(int) == sizeof(float)) {

float f = 0.0f;

int *ip = (int *)&f;

printf(“float is %f\n”, f);

(*ip)++; // diagnostic required

printf(“float is %f\n”, f);

}

}

5.2 Accessing freed memory [accfree]

Rule

After an allocated block of dynamic storage has been deallocated by a memory management function,

the evaluation of any pointers into the freed memory, including being dereferenced or acting as an

operand of an arithmetic operation, type cast, or right-hand side of an assignment, shall be diagnosed.

Rationale

C identifies the situation in which undefined behavior arises as a result of accessing freed memory:

UB Description

The value of a pointer that refers to space deallocated by a call to the free or realloc function is used

(7.22.3).

Example(s)

EXAMPLE 1 In this noncompliant example, a diagnostic is required because head->next is accessed after

head has been freed.

struct List { struct List *next; /* . */ };

void free_list(struct List *head) {

for (; head != NULL; head = head->next) { // diagnostic required

free(head);

}

}

EXAMPLE 2 In this noncompliant example, a diagnostic is required because buf is written to after it has been

freed.

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

if (argc < 2) {

6 © ISO/IEC 2013 – All rights reserved

/* . */

}

char *return

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...